Insofar as totalitarian thinking is inextricably linked to the question of totalitarian rule and the historical experience of National Socialism and Communism, the fundamental question of what makes individuals so susceptible to totalitarian ideas has been neglected. This omission helps explain why it has taken so long for a psychology of totalitarianism1 to emerge and why such an attempt risks falling into the trap of mass psychology. This is certainly understandable because, as Marx tells us, »Religion is opium of the people,« meaning such attempts would be understood as a form of mass hypnosis – and consequently: as totalitarian thinking. However, this would have branded all non-secular societies as totalitarian by making the holistic nature of the pre-prescriptive world—the participation mystique, as Levy-Bruhl called it—a signature of totalitarianism. This would be reasonable to consider insofar as every religion provides its believers with a reservoir of meaning which, by closing life's open questions, takes away their fear of life – or, following the thought of the religious scholar Rudolf Otto, paints over the Mysterium tremdendum with the Mysterium fascinans, thus banishing horror with religious awe. In this way, a wholeness or grand narrative is established, transforming the immediate experience, the fragmentary sensory world, into an order. While, in this respect, every religion may have an inherent totalitarian dimension, understanding totalitarianism isn't best served by short-circuiting it with the religious because, by doing so, such a perspective sacrifices this thinking’s modern dimension. For totalitarianism is Enlightenment’s dark companion, which joins it in the same unexpected way as Dr. Jekyll joins his Mr. Hyde.2 If one insists on the religious character of a particular totalitarianism, it would be more logical to speak of a religion without religion – a Machine of meaning that, regardless of its inner worldliness, appears with a dogmatism otherwise only known from religions. That’s precisely the signature of the totalitarian ideology found its great storyteller in George Orwell - after all, with his reference to groupthink, he can explain how it’s possible that 2x2 equals five.

If ideology can override reality, indeed its own sensory apparatus, we've identified a first characteristic of totalitarian thinking: namely, what could be called a blindness to reality or ideological blindness, depending on the case. Because the thought construction prevails, people endeavor to banish all realities not corresponding to their circle of vision—or, if they can’t, they are symbolically banished, even resorting to physical violence. Following Freud's distinction, such behavior would be called psychotic.3 However, we refrain from this because we’re not dealing with an individual deviation but a collective one. As Nietzsche once remarked with beautiful brevity:

Insanity is something rare in individuals, but the rule in groups, parties, peoples, times.

With this, he makes it clear there’s not much to be gained by regarding totalitarian thinking as insanity, indeed as a mass psychosis. For insofar as it occurs en masse, totalitarian thinking isn’t experienced as psychotic but takes on a regular, thoroughly rational appearance. It frequently even takes on the form of a social commitment – thus becoming the glue providing a group, a party, or a nation with a sense of belonging. While National Socialism and Communism may show some affinity to religious thinking, the phenomenon becomes much easier to read if we look at totalitarianism’s modern form instead of resorting to religious interpretations. If, structurally speaking, the mass character is characteristic of totalitarian thinking – and if this is what precisely sets it apart from traditional religiosity, then the logical question is: How does modern mass society come about in the first place? My answer, as set out in the image and metaphor of the twitching monks, would be that modern mass society emerged with the discovery of the vacuum and electricity. This is where the telematic society, which has become a global order in the form of the Internet, becomes conceivable. When Lenin said, »Communism is Soviet power plus the electrification of the whole country,« his remark suggests that ideological conformity presupposes technological conformity. Although forms of mass virality can already be observed in the early days of electricity—in Mesmer's salons, the societies of harmony, or in the shadow of Puységur's magic tree—mass psychology only becomes a significant topic towards the end of the 19th century, the time when the telegraphic public sphere was no longer a promise but an everyday fact. Gustave le Bon – and his successor, Sigmund Freud – fail to mention this technological dimension. If we follow them, we’re dealing with a form of hypnotization where the will of the individual is transferred to the masses. Infected, even intoxicated by the mass excitement, the individual is absorbed into the movement of the collective. If this phenomenon takes on a physical form at mass events, where an entire collective can act as one man, the mass can also imprint itself where it isn’t present, and then we could speak of a cooled, formalized mass aggregate. In Being and Time, Martin Heidegger captures this in the form of the One [Das Man4]. By behaving as one behaves, the individual's center of will and individuality are ceded to a mass subject. In this sense, you could say that totalitarian thinking begins where the mass in me—as the Heideggerian One—takes control.

When the mass soul—meaning totalitarian thinking—coincides with the emergence of the mass media, a genuinely modern kind of causality is relieved-out. Interestingly, this is the subtext of French philosopher Julien Benda's great lament in his 1927 The Treason of the Intellectuals [Trahison de clercs].

Benda's observation coincides more or less with the advent of radio and was published in the same year as Siegfried Kracauer's The Mass Ornament, so it is hardly surprising. You only have to look at Brecht's media theory, where, anticipating the internet, he understands broadcasting as a mass communication apparatus. So he realized mass media turns a society into a mass formation: Das Man. What's new here is when an individual sits alone in front of their radio, television, or computer, there’s no longer the need for a physical connection with the mass and the corresponding mass hypnosis. In this sense, Abbot Nollet's 1746 experiment, in which he gathered two hundred Carthusian monks and energized them with a capacitor, is a metaphor, indeed, the archetypal image of modern mass society. If there's an unmistakable physical presence in the image of the twitching monks, then it's been translated into virtuality – that is, in the image of the mega-monad that’s cooled into a machine. The isolation of the listener can increase this effect because he runs the risk of unconsciously subordinating his own will to the will of mass media and is inclined to mistake the received meaning for his own will—meaning transference.

If Riefenstahl’s images of the Nazi’s 1934 Party Congress Rally broadcast the »Triumph of the Will«—no, even more, the Triumph of Totalitarianism—the image of the State's Totality obscures the much more fundamental question of what makes Modernity’s inhabitants so receptive to this totalitarian temptation. Hannah Arendt, who spoke of social atomization in this context while ascribing a significant role to existential homelessness, indeed the displacement of contemporary individuals5, may have been a much more sensitive observer than Wilhelm Reich, for example, who made repressive sexual morals more responsible for this receptivity. This interpretation, laid down in his Mass Psychology of Fascism lead to the oft-cited study on the authoritarian character presented by the Frankfurt School in 1950. Now, one of the paradoxes of the present is that sexual liberation, indeed the overcoming of authoritarianism, has by no means brought totalitarianism to a standstill. Au contraire—one could even speak of a totalitarian renaissance. The paradox is that the postmodern variety no longer requires mass gatherings and that one can devote oneself to the mass soul on one's own. If we've spoken of a religion without religion, this paradox could just as easily be applied to the masses; we could speak of a mass without mass. Such an interpretation is also instructive for psychological reasons. For precisely, this isolation, this feeling of inner homelessness and rootlessness makes the inhabitant of postmodernity – the free radical – so susceptible to totalitarian connections. This fills the inner emptiness – and the person, armed with identity politics, acquires a corresponding self-confidence.

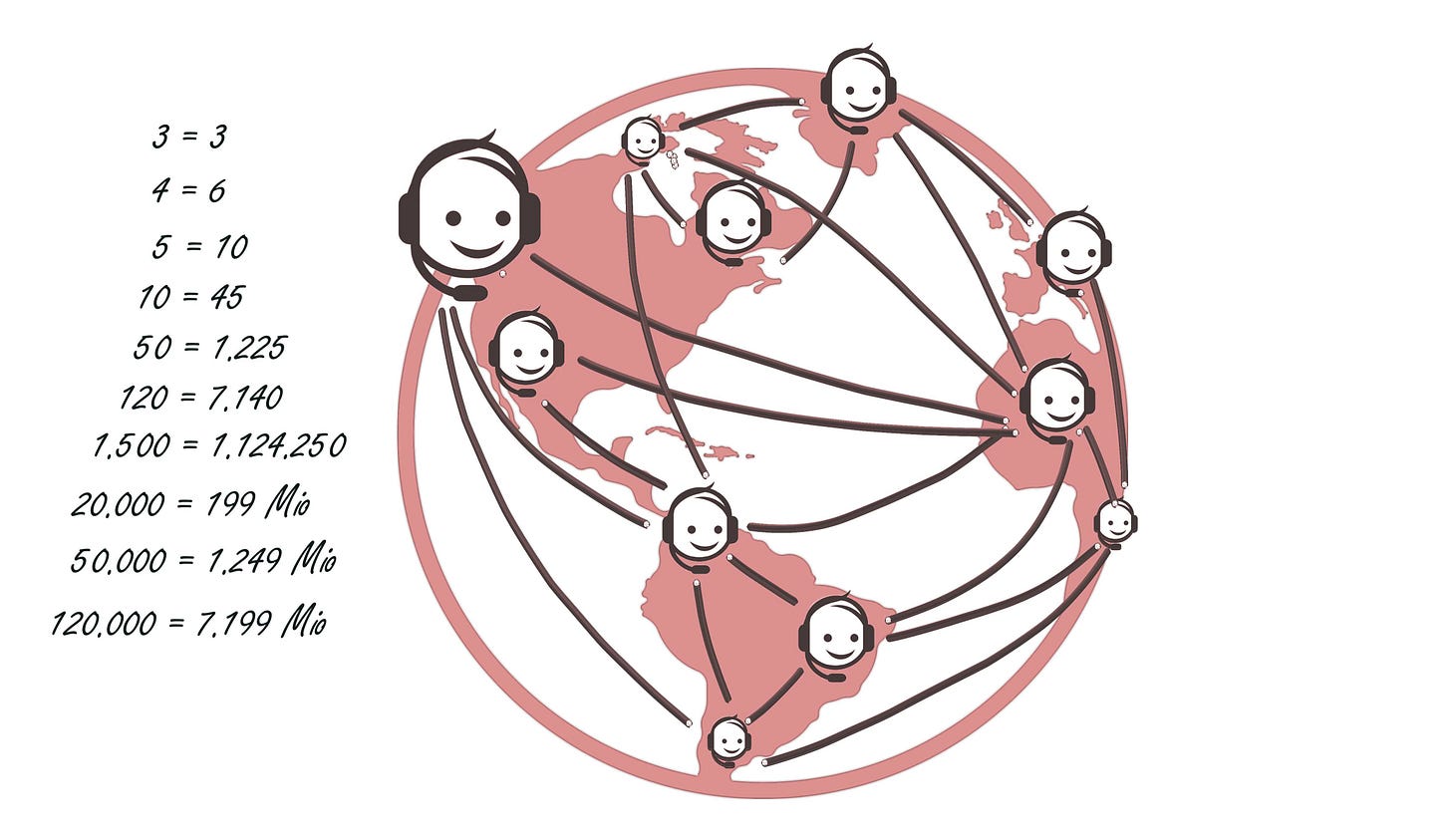

If I've introduced a distinction between hot metaphor and cold formalization, it's because the mass soul's logic, in parallel with technologisation, is accompanied by a cooling – and, as a result, its character of massification is increasingly fading away. What we’ve come to call the filter bubble precisely contains this. For this reason alone, it's worth thinking about Metcalfe’s Law, the so-called network effect phenomenon first formulated by the inventor of Ethernet, Robert Metcalfe. The idea is simple: two people connected have only one connection, three have two connections, and four have six connections. If you increase the network to 100 people, you would have 4,950 connections—while if everyone in a small town of 20,000 inhabitants were to network with each other, there would be a dizzying 190 million and 990,000 connections.

Transferring this to populations, or more precisely, to groups clustering around a particular fascination, phantasm, or fetish, you can see that every fringe group, no matter how marginal, represents an echo chamber that, in terms of its power, can compete with any mass formation, no matter how imposing—even outdoing classic media groups.

In this sense, anyone who likes a tweet or, as an Avatar, is gathering a particular following and acting in a field of virality.

Previous attempts to address this using mass psychology failed wherever the phenomenon was presented as the formation of an individual opinion. Insofar as we're dealing with the privatization of the masses through the Machine and the Network Effect, the distinction between free radicals and the masses begins to blur - the multiplier and influencer as a mega-subject begins to rear its head. Strictly speaking, this is a dichotomy: If we have the unarmed, analog, and finite self on one side, then on the other side, there’s the avatar, the online existence accessible to everyone worldwide – 24/7. Bearing in mind the formula on which the digital order is based, x=xn, the psychological asymmetry is quite obvious. Because, even though the unarmed self is always thrown back on itself and its own limitations, the digital magnification of online existence harbors a totalitarian temptation – especially where there’s the inclination of ›giving sugar to the monkey‹ as a thymotic charge. Or put another way: in the form of online existence, the totalitarian temptation comes close to the individual, even crawling into the spaces where the lonely self longs for belonging and socialization. What used to be a state of emergency unleashed at folk festivals and football stadiums in carnivalesque form is now becoming an everyday occurrence where the free radical tries, with a click of the mouse, to console himself over his isolation and depression.

With this in mind, our contemporaries’ susceptibility to totalitarian ideas is no longer surprising. What's more, we understand why totalitarianism no longer only forms on society’s fringes but has suddenly arrived in its center—in an utterly surprising form. Let’s take the harmless-sounding claim of so-called safe spaces that have spread across universities in the wake of identity politics. While it's remarkable enough that people believe they must protect their fragility with such a cordon sanitaire, the politicization of the self-evident testifies that your own identity no longer exists – indeed, that you can only assert it in a totalitarian way, in alliance with like-minded people; and because this action is usually aimed at an enemy, you can now impose the responsibility for your vacuum on them. In the Weight of the World, Peter Handke noted that the only political act he could imagine was running amok, outlining the final solution to the deep narcissistic humiliation imposed on the free radical in the digital age: that in virtuality, you can no longer distinguish yourself as a virtuoso, making it difficult for the individual to survive in the population of his Avatars. In this sense, overcoming totalitarianism isn't political; it’s an existential task. We must realize what it's like to lead a meaningful, humanly connected life as a dividual. Conversely, our refusal to recognize this narcissistic humiliation inevitably leads to a singular susceptibility to indulge in all imaginable thought patterns, conveying a sense of wholeness to the individual – bringing the lost paradises back to the present. If the individual succumbs to this totalitarian temptation, then, unlike the totalitarianism of the 20th century, it doesn’t articulate itself as mass hypnosis but can, in a polymorphously perverse way, take on a variety of forms. If the battle cry of the present rhymes with equality, diversity, and inclusivity – and if, on the other hand, it's joined by a Great Again, then we know: The totalitarianism of the present is as colorful as life is colorful!

Translation: Hopkins Stanley and Martin Burckhardt

The Belgian psychiatrist Mattias Desmet published a book with this title in 2020. See Desmit, M. – The Psychology of Totalitarianism, trans. E. Vanbrabant, Vermont, 2022.

This is also reflected in the etymology of totalitarianism. The adverb totaliter means entirely or fully, which in English can refer to a machine for registering/showing the totality of operations, measurements, and the like, that, in the 19th century, became incorporated into German from the English totalizer as a counting device used for horse betting.

Here, Freud makes a distinction established to distinguish between neurosis and psychosis. In a small thought experiment, he imagines a young woman standing before the deathbed of her sister, with whose husband she’s hopelessly in love. Now she could tell herself: ›The field is not open to the brave!‹ But because filial piety at the deathbed makes such a thought unthinkable, the neurotic is forced to repress it. But what does the psychotic do? Her answer to the moral aporia is as simple as striking: she convinces herself that her sister is not dead.

Das Man or The Man is an essential Heideggerian leitmotif that’s often translated as ›the They.› Because the German Das Man is neuter, it can refer to an indeterminate plurality of a massification of people best captured by the One in Englisch.

»The truth is that the masses grew out of the fragments of a highly atomized society whose competitive structure and concomitant loneliness of the individual had been held in check only through membership in a class.« Arendt, H. – The Origins of Totalitarianism, New York, 1962, p. 327.

Related Content

Postmodern Demonology

If, when reflecting on the fatalities of today's culture wars, with its encroachments and infringements by self-appointed language police, we're reminded of George Orwell, of his logic of Oldspeak and Newspeak, thoughtcrime and the Ministry of Truth, it's no coincidence. Like few others before him, Orwell grasped the abysses of totalitarian thinking. He…

Downwards!

When we speak of totalitarianism, we often conjure up this image of an all-powerful, fearsome state: a portrait of the Leviathan, drawn as a monster! Franz Neumann, the unfortunately forgotten political scientist, provides us with a structural analysis of Nazi rule that brings a very different perspective into relief – one that’s extr…

Germany, a Winter's Tale

We live in strange times. It almost seems we’ve stumbled into a never-ending witching hour, with ghosts returning we’d thought had long since finally been laid to rest. Take the phenomenon lèse-majesté [Majestätsbeleidigung]. If this lèse-majesté seems as bizarre and alien to an American as an unknown word, everyone in Germany know…

I am so glad you found this helpful, as I also found Martin’s thinking helpful in filling in so many unfinished thoughts.

As for the Boolean formula, x=xn, it’s about the logic of scalability and proliferation threat. Remember that Boolean Algebra is more about logic than mathematics. Martin wrote a wonderful description of this in »The Shadow of Things: How to navigate in a post-material World.«

[https://martinburckhardt.substack.com/p/the-shadow-of-things].

Best – Hopkins Stanley

Thank you! This is insightful and helps me with a number of unfinished thoughts.

One thing put me off: your formula "x=x^n". I did not understand what it is supposed to say. Did you mean "y=C(n,2)", the binomial coefficient? At least that is what you were using in your city example.