The Shadow of Things

How to navigate in a post-material World

The Shadow of Things originated in 1996, at a time when museums, suddenly confronted with digital artifacts, had to undertake a re-evaluation of their own collections. And because Martin's Metamorphoses of Space and Time1, published in 1994, told the cultural history of our transformation from a mechanical worldview to a digital order, the Werkbund approached him asking for a lecture on the disappearance of things leading to this essay2. While Martin's first text, Digital Metaphysics3, attempted to make the transition to post-materiality tangible, this essay gets to the heart of the epistemic rift. Here, we playfully encounter figures of thought that have become some of his thought labyrinth’s central leitmotifs, occasionally even becoming the subject of his major works such as the electrified monks of Abbé Nollet alongside Boole's ›world formula,‹ Snow White, the suicide of Alan Turing, and the question on what the disappearance of things and the Atomic Bomb might have in common.

Hopkins Stanley

The Shadow of Things

To speak of the disappearance of things has almost become a cliché, but at least it's one that has reality on its side. Or, more precisely: it’s derealization because that's what our Symbolic Machines achieve – why—with a sense of the oracular—we aptly call them Media. Now, as an antidote to the eagerly consumed oracular sayings, and perhaps also to avoid taking the beautiful formula too literally, we’ve become accustomed to saying that all of this wasn't true – that it was just a simulation and Death wasn't really dead—but we can't avoid admitting that this supposedly unreal, merely symbolic world has itself become concrete. The lament about it is as great as the insight into the change is small. If instead of just vaguely surrendering to the sense of loss, we want to face this self-made reality; then we need to study these Symbolic Machines with which we construct our reality – the reality beginning to feel so uncanny that we perceive it only in terms of loss.

From this point of view, I'd like to draw our attention to the history of things, to the fact that our perception of the shadow, too—however much of a natural companion it may seem—is a construction of our perception. In painting, it's an invention coming about only in the 14th or 15th century – and only since then has this pairing of the Thing [Ding] and its Shadow made sense. Even more paradoxical: it's the Thing's shadow giving it its weight and gravity, detaching it from the wonder world of relics and assigning it its place in the World. Suddenly, there are no longer any symbols to be seen there which, on the ladder of godliness, denote a level of everyday things between earthworms and seraphim: an apple, a chest of drawers, and a mirror. And with these mundane things, a new, inner-worldly sense of order becomes apparent, as they are placed in a relationship and an order to one another that’s no longer god-given—but the work of man. Figuratively speaking: In place of the aureole that surrounded the medieval saints, there’s now the aura—meaning: the Thing’s appearance can only arise in the shadow of things, where things point beyond themselves: where an Apple, however naturalistically it may be painted, is more than just an apple….bringing me to the hypothesis that the shadow's construction is the other side, that is, the shadowy side, of what I consider to be a Thing.

In other words: the Thing and its Shadow are one, and their unity stems from the fact that they belong to a common Symbolic Machine, which, in this turning, makes clear how we perceive the world around us—the way we think. To me, it isn't so much about the things as such, but a turning toward the question of the light in which we see them, how we expose them. This exposure no longer takes place in a Platonic cave, nor does it refer to the Nature of Things, but it falls back on us as a reflexion of ourselves. And by dint of finding this bond so compelling because it’s not one of nature but of history, I will tell two little stories, one banal—concerning only me—and the other terrifying, which marks the bondage under which we all [miteinander] stand together.

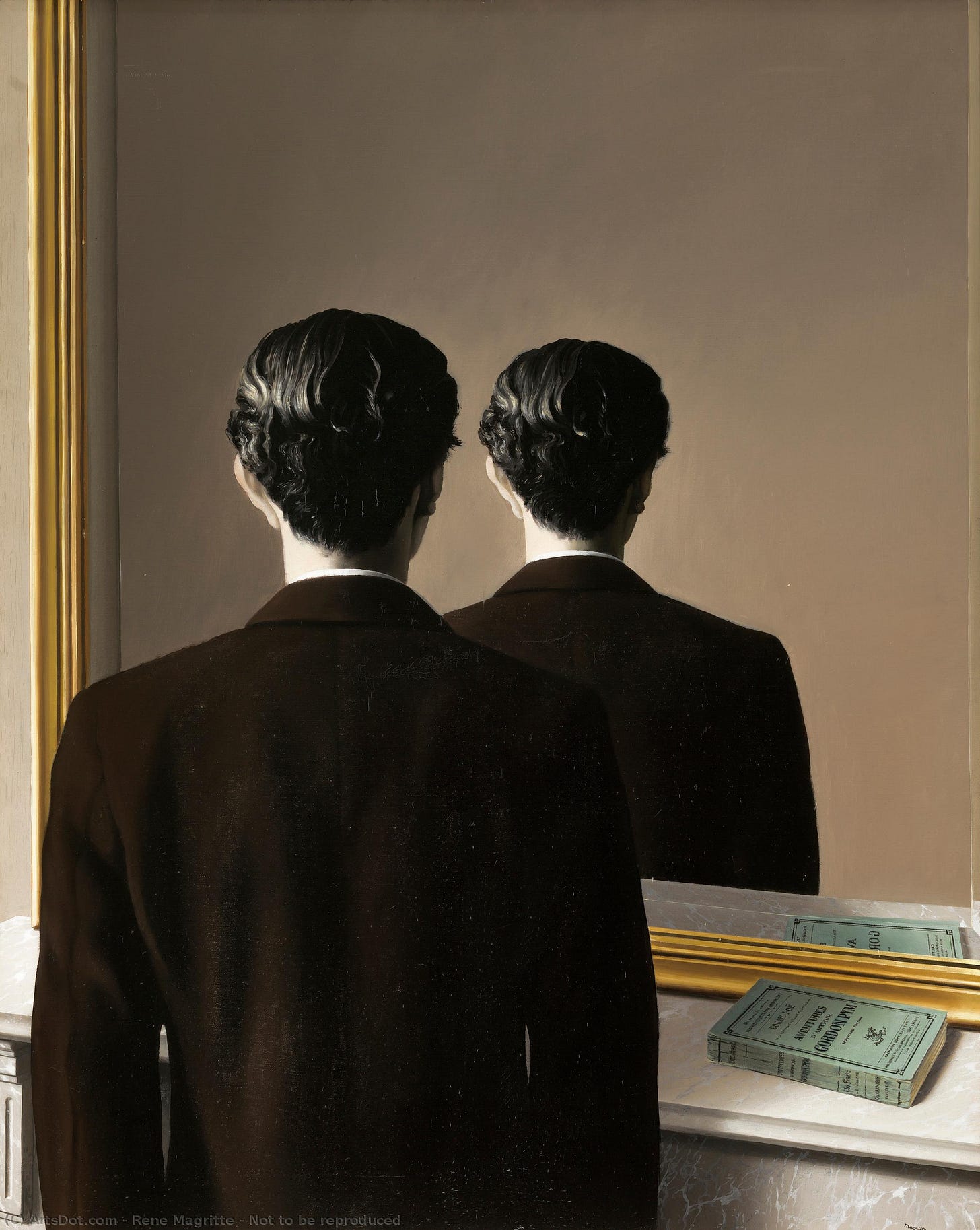

Let's start with the banality. I remember: I was a pupil sitting at my desk correcting the red-marked mistakes in my German essay. I was reading the comment, written in headmaster Dr. Broer's dashing hand, that there was a difference between being the same-self [dasselbe] and the same and equal [das gleiche] as my eye fell on the picture above me, which I'd attached there with drawing-board pins, a painting by Magritte, which of course was a poster—a reproduction. And while endeavoring to grasp my teacher's comment, looking at the painting in front of me, I wondered with growing bewilderment: If it's a reproduction that’s hanging in another place where someone like me is sitting under this same image – and what's more, is a secret companion sharing the same fate [Schicksalsgenosse], now also occupied with solving the same grammatical problem—is it an image of the self or the self-same? Is it the same or the self-same grammatical question? I remember brooding over this while sitting at my desk and, in my deepening rumination, finally looking it up in Duden’s to read: ›Identity can refer to an individual, an example, or a class. In general, the context reveals which identity is meant.‹, with the exemplum, ›All men wore the same hat.‹ That might still be approachable, I thought. But then what about this? Is ›No one ever steps in the same river twice,‹ the same or the Same One? Duden says ›It's always the same; Susanne is wearing the same dress as yesterday,‹ and right there was when I realized you can't ask the Dictionary about Philosophy—that it's nothing more than a symbolic dress code.

But thank God, you outgrow the clothes of adolescence and the torment of pleasing the headmaster. And so, many years later, I stood before the real painting—the original, as they say—and it was much smaller and more modest than I’d expected. And what's more, you could see what the reproduction had so graciously covered up: the clumsy, heavy brushstroke. My first reaction was that it seemed like a copy of my reproduction wasn’t particularly well-made—not that I didn't recognize the picture. But it wasn't identical to it, it wasn't the same [dasselbe], it merely resembled it. Well thought out, but not well done, or so I thought – until I realized the absurdity of that moment. Because, undoubtedly, I was standing in front of the picture whose reproduction I’d hung above my desk – but right here, in my non-recognition, lay the secret. I realized that the photographic reproduction hanging above my desk wasn't just a likeness but was literally: photogenic – it'd conjured up a quasi-larger-than-life phantasm in me that the real image, created by the painter’s hand, could no longer match. The image, or better: the impression I'd formed as a reflexive archetype of the original, had taken the original's place. But with that, the original had, in a confusing way, fallen out of the world – and if it still had a place somewhere, it was only in my head—in the head of the observer; it was a Spectral Thing, the phantasm of my imagination, which I'd conjured up, looking at the poster above my desk: larger than life.

The other story goes back even further – to August 6th, 1945, before I was born. Strictly speaking, this was only a blink of an eye, but it's a blink that only very few who’ve seen it have survived. It's—as you may have guessed—the overpowering flash of light that reduced Hiroshima to ashes and ashes. At that moment, when the flash of the bomb fell on things and bodies, those who were near the explosion core were incinerated by the unleashed heat; they simply burned and glowed – so that it would be easily stunned into saying: they disappeared without a trace. But that's not quite right because there was a trace of the disappearance. In the moment of the bomb's flash of light, when its power destroyed the bodies of things and people, it also burned its shadow into Hiroshima’s earth and the walls of its houses – a bit like the flash of a camera that casts its own shadow. As in my photographic reproduction, the light had a photogenic effect here, too, as it captured this moment of destruction that immortalized the objects, as one says with enough ambiguity, in the blink of an eye. The disturbing effect emanating from this photogenic, or, more aptly, photo-destructive shadow image stems from witnessing an exchange between the Thing and its shadow corresponding to the one occurring between the original and its image. In the atomic illumination of the body, the shadow, as its most ephemeral, most fleeting presence, is immortalized here, becoming the most real part of the body.

Some concluded that the end of history has dawned—and yet, seen from a different perspective, it’s only just beginning. For this shadow, burned into the ground, doesn't quiesce but continues irradiating [ausstrahlen], so we're dealing with a moment not wanting to end, the image of a simultaneously preserved and ongoing annihilation, a story that, precisely by disintegrating, lasts, through now and into the future.

This image, this trace of disappearance, haunted me for a long time – so much so that it seemed to me to be a kind of symbol: as if it contained the dark side of Modernity – as if in recapitulating this moment in my mind's eye, I was looking into the eye of a sphinx. And isn’t it so? Are we not witnessing the loss of the protective shell, aura, and atmosphere of things, their peeling, hollowing out, and disintegration? Doesn't the bomb's illumination and in the way we bombard things – symbolically and photographically – reveal the same logic? When speaking of radiance [Ausstrahlung] in this context, do we not take our language more seriously? Need we not admit that to the extent something radiates [ausstrahlt], it, in turn, gives away mass, becomes lighter, and loses substance? That it, in other words, begins to radiate and lose energy [verstrahlen]. For therein lies the dialectic of the camera and its photon irradiation: Nothing can be irradiated [bestrahlen] and exposed without a cost, and the objects of this irradiation must pay for itself with a loss of substance—inevitably entering into a process of radioactive contamination [Verstrahlens]. This contamination doesn't occur only where it can be measured with Geiger counters but also encompasses the symbolic space. And it’s only against the background of such symbolic radioactive contamination [Verstrahlen]4 that the statement of a war correspondent elaborating on the half-life of his images and the fact that the horrors photographed—like the images of torn bodies only remaining fresh for one television morning—can be understood. Here, too, where symbolic reproduction, or more precisely: symbolic death is at issue, Einstein's formula can easily be applied: E=mc2. This formula states that mass can be converted into energy and vice versa. Whether we understand this formula is completely irrelevant because we've been living in it for a long time and, as inhabitants of a mass society, we practice reciting it in new and ever-different ways. That's Modernity’s signature: that it makes the individual become mass – and it also gives a student brooding over his German essay the privilege of immersing himself in the world of René Magritte. This is why, if only out of gratitude, I don't feel inclined to condemn this reality. But as I said, there is a critical point, namely where the Thing, bombarded with an excess of energy, begins to melt at its core, where its nucleus decays and turns into pure and negative energy. Where it shatters and begins to dematerialize. This is precisely where what we previously perceived as radiation [Ausstrahlung] changes into a form of radioactive contamination [Verstrahlens]. The sign changes: it appears symbolically contaminated, irradiated [verstrahlt].

Seen in this light, the perplexity and helplessness you sometimes experience when looking for a gift in a large department store isn't a coincidence. And not just because the person to be given the gift already has everything they need for their happiness, but because the signature of all these things, which present themselves to the eye, points to something contradictory to the gift's intention: because it should be one of a kind and something special, and not part of a series.

But of course, no matter how you twist and turn it, this isn’t the case—which my extremely practical mother solved by: 1) always leaving the tags on it, and 2) accompanying the presentation of the gift with the words ›So if you want, you can exchange it!‹ This right of exchange is where the drama of things lies, consisting in their gradual indifference: as they become ubiquitously mass-produced, they seem to evaporate. And just as I can no longer see the forest for the trees, it can also happen that I realize there's nothing worth giving away in a vast department store packed full of things. And not because there's nothing, but because what’s there bears the wrong signature because it doesn't mean for a particular loved one, but everyone. So it's no coincidence that when it comes to such a gift, we turn to ephemeral things like flowers, perfume, chocolates, or the spiritual things we prefer to give: books, pictures, and music. The antiques. The unique pieces. The handiwork. Everything that falls outside the series.

So, what am I looking for? When the Good, as such, isn’t good simply because it fills a lack – then it becomes a question of aesthetic judgment. Literally, it becomes the stuff of Art—and that’s what we can observe in the emblems stuck on things. Perhaps the history of these emblems best illustrates the metamorphosis of our material world: we see how the old, touching descriptions have been transformed into quality seals, how things are accompanied by collector's pictures and small additions supposedly designed to make them more appealing – we see how artificial and crackling skins replace the rough packaging, how the appearance becomes increasingly refined and aestheticized, how a design inscribes itself (which, not coincidentally, in its rough approximation, plunders the sign language of so-called Classical Modernism)—how a logo gradually emerges from this constant inscription. It's as if the inside of things was turned inside-out—as if their core was transformed into the kind of charisma smiling down on us from billboards. But what is this core? A woman's big red mouth? A shiny, well-toned muscle? What does a Camel have to do with a cigarette? If we question its emblematic divestment, then we can almost speak of a silencing and shadowing of things, even if it seems as though the logo itself has become the Thing's epitome, as though it alone is this projected sign that assigns things (as its former shadow did) their place in the supermarket world. – Suddenly, the big wide World has taken the place of the things, a haze, or better yet, a sensation no longer pointing to what it's offering me, instead it’s pointing to me, the one desiring – and in this way, the structure of desire unravels, it makes clear that things were never just things but have always been formed by desire. It's only that I, who lacks nothing, no longer desire things – instead, it's the desire for what's lacking for my happiness: thus, happiness itself, which lies in my being-there [Da-sein], in the way I arrange myself in art, how I become the artist of my own life's Work of Art...and yet, however smoothly the consumer world accommodates itself, however hard it tries drumming into me the authentic way of life, the art of sitting, standing and lying correctly, the art of dressing myself appropriately and, in good time, undressing again—its enjoyment nevertheless leaves a quietly increasing feeling of displeasure because there’s a structural dissimilarity between me and things. For these things are not one like I am one, but many: they look down on me from every billboard, larger than life.

They don't correspond to my hand, but on the contrary: in their industrial perfection, are denying any kinship. They promise me a sense of life, but in the blink of an eye, when they are standing concretely in front of me when they are supposed to fulfill it – my desire bounces off them—and suddenly, in their serial logic, an unpleasant materiality emerges: that one isn't dealing with Art after all, but only with imitation art and plastic material [Kunst-Stoff]. They stand around in the room like unwanted gifts – as if the society that gave them to me is still symbolically present in them and unwilling to release me from their serial production—in this sense, the Good left to me is no longer good, but a poisoned gift [Danergeschenk], a Trojan horse. If I endure this thing in my environment any longer, the giver's sardonic smile will have to emerge: Don't you think it's beautiful? With this assault on Art, of course, something simple emerges. Namely, it’s not (as my mother used to say) the things that smile at us but the thinking symbolized in them. And whatever we may call it: whether we believe the logo, the story, or our desire, all this is something that doesn't coincide with the Thing’s opacity – but instead points to that symbolic bond binding us to things—that it’s not about the things, but about material plasticity, about the light in which we see them. And that is what the logo says: That its what I think it is.

Kant says: the Thing, we cannot know anything about, the Thing X—which is a mathematical paraphrase of his other, more famous formulation of the Thing-in-itself [Ding an sich]. By which it's been said that this Thing X is and must remain an unknown with regard to us, for the simple reason that every Thing leads us back to the nature of things – and of this, Kant teaches us, we know only that which we have previously placed in it. Seen in this way, things are a mirror of ourselves. Kant has thus, in a masterly fashion, both identified the problem and allowed it to disappear again into his philosopher's head—for hidden in this X is the fact that, before we set about constructing things, we desire them above all – we're always dealing with objects of desire and longing: that we're not so much concerned with seeing our ordinariness reflected in things, but that we're looking for the Other, the Alien, the unheard of, the new and unprecedented. Ancient magical faith lives on in things—a mirror of our desired-things, their resonating bodies: Fetish-Objects. Things to which more should cling than the material substrate, something supernatural, mysterious, something that is more than mere Thing. Perhaps, strictly speaking, the archetype of such wonder-things is the relic. Or the meteorite that fell from the sky as a gift from the gods was remelted into the nail for the cross. Going back just a little in history, we see the concept of the objective loses its meaning, and we can no longer avoid the impression that things have never been objective; they have acted as disguises for the unconditional—or more precisely: the longing for the unconditional in all cultural stages.

Undoubtedly, this way of looking at things clearly clashes with the Worldview of assuming a Thing is that which lies outside us and exists – as an objective object, so to speak, independent of whether and how we look at it. This attitude certainly has its sharpest expression in Cartesian philosophy. Here it is the res extensa, the idea of the Thing as a geometric body suspended in the coordinate network of Space and Time. This Thing should be nothing other than Thing; it should be structurally separate from the World of Thought – and, as is well known, this is where the schism between the World of Things and Thought, between where the Humaniora and the Natural Sciences lies. Of course, if we follow the genealogy of Cartesian thought, we quickly come up against unheard-of paradoxes: at the center of this Philosophy, which asserts the primacy of the mind, is, strangely enough, a Thing, namely the Mechanical Clock – or, as Descartes said, the Automaton. Let's listen to Descartes' comments on this strange Thing: »It is no less natural for a clock, he writes, which is composed of these or those parts, to tell the time than for a tree grown from this or that seed to produce the corresponding fruit.« Here lies the whole magic trick, the hocus-pocus of Cartesian philosophy. For by equalizing tree and machine, Descartes claims something like the nature of the Clock - and so it's obvious to take his man-made mechanical laws for natural ones and to impose a genetic code on Nature—which is, of course, nothing other than a spawn of his own thinking. This allows us to follow, in a didactic example, as it were, what Kant meant by this dictum about the Thing X, for we become witnesses to how the philosopher succeeds (via the phantasm of the Machine) in making himself and others believe that living beings are nothing more than natural automata - whereby he only brings to light about nature as what he has previously put it. Of course, as undoubtedly as our concept of the object, of the actually dead Thing, has its root here, this is by no means the end of it—for if we pursue this Thing X, with which Descartes reinterprets the World as a large clockwork, we're confronted with an even more confusing paradox: namely, that this symbol machine isn't a product of the rational 17th century, but an artifact of supposedly dark times, namely the 12th or 13th century.

It’s not the concept creating the tangible, but the other way around: the concept arises from the tangible. Or, if you want to put it more provocatively: Descartes isn’t an innovator of thought but someone who came a few centuries too late. Or, put differently and just as paradoxically: if you insist on such an epoché, then you’d have to shift the Modern era’s beginning all the way back to the Middle Ages–it's this phase-shifting paradox of the Thing preceding Thought that prompted me to examine this question more closely. The conclusion I came to in reflecting on all these questions wasn't only abandoning the idea of the object but conceiving of things as hypostasized—as embodiments of the mind. In this sense, Descartes doesn't use a metaphor when he brings the clock parable into play but mobilizes the mental potency already reified in the Thing: the logic of the Wheelwork [Radërwerk] —but this means he's merely expressing out the philosophy already inherent in the Thing. Here, the significance is that this print-out [Ausdrücklich-Werden] accompanies a misrecognition of the Thing. That what was a cultural achievement is reinterpreted as the nature of things. The Thing that human ingenuity has brought into the World becomes a meta-physical Thing, an Un-Thing, a transcendental Machine. Not we—this is the core of this philosophy—it’s not we who have brought it into the world, but the law of nature. This is undoubtedly a convenient view of the World, as it finally allows us to think without thinking – or, as we might say: to think automatically. However, the price of this well-functioning thought apparatus is that you also acquire an unconscious—not somewhere on the margins, but right at the center. When thought ceases to forget its conditionality, it dissolves the bond connecting it to its Symbolic Machine – and the Thing becomes an unconscious object.

Let's just take our talk of factual constraint, which—in good Cartesian tradition—we constantly talk our way out of as if, independent of us, there were a nature of things or a cunning of the object. However, that's not true at all; instead, when we talk about a »factual constraint,« in truth, there’s a compulsion to think, which has only taken the form of a material Thing [Sache]. This reified thinking, enclosed in the artifacts or actuality: carried out into reality, is ahead of that which defines itself as thinking – and in such a way that what we call thinking is damned to reflection—or, at worst, to a systematized perceptual disorder. And that’s precisely what we observe in Cartesian thinking. In a sense, this comes close to a philosophical bankruptcy because we must recognize that the philosopher of the Modern Age: 1) comes too late, and 2) in coming too late, he's also mistaken about the nature of the things that become his World-defining Machine – and so thoroughly that we must conclude that precisely where he constructs the supposed rational object, he is, in truth bringing a new scientific miracle into the world, nothing less than the fetish of the pure object. Here, we can see how the mechanistic philosophers, when they speak of their Symbol-Machine, are continuing the tradition of the medieval proof of the existence of God. It's no coincidence that Kant begins his so-called critical phase with the analysis of the ontological proof of God's existence, that he, what the philosophers have previously hidden in their thinking as God's program – even if it's only as the small t (for the ticking of the absolutized Wheelwork time, shot up into the sky shot) – that he brings this out again: the Thing X, of which we cannot know.

The Thing X. This is a beautiful formulation. Not only because it touches on the unknown—which describes our desire for the other—but because here, when we move from this formula to another, we can trace how the silencing of what we can’t know comes about. And here, too, we’re referring back to the beginnings of Modernity. The formula we're now going to discuss, which succeeds the Cartesian Wheelwork Automaton, is just as much connected to the birth of the computer as it is to what Walter Benjamin refers to as technical reproducibility. It’s the simple fact that things proliferate, that they’re serialized and multiplied. And the formula erasing the self-imposed ignorance of our Königsberg philosopher is precisely of this kind: x=xn.

It is the formula—and I emphasize emphatically—underlying our thinking, our ground plan formula, our foundation of Modernity – and because, very strangely, it’s half-forgotten, I want to recapitulate what it’s all about briefly. It’s not that we aren't familiar with this formula. We deal with it day in and day out – if not in its a priori form, then at least in its consequences: the operands of the AND/OR/NOT. X=xn—that is the basic formula of formal logic, or, as it is also known: Boolean algebra. Its history takes us way back to the 19th century, to a young school teacher and mathematical autodidact named George Boole, who for a time considered becoming a priest. The latter is essential to remember, as he was convinced that mathematics was how God made himself understood to man.

Let´s look at his formula: x=xn – which can be extended at will to = x3, = x4, = x5, and so on. While this sounds reasonable in our context, where we're dealing with the serialization of things, but mathematically, it’s – as far as our school training can enlighten us – rather strange. This formula applies only to the zero and one in our entire number system. If I multiply one by any number, the result is always one, just as zero added to any number results in the same number. Of course, this isn't coincidental because the entire number system we're familiar with rests on these two numbers—these two pillars of thought. Now, I'd like to point out that this system isn't a natural product either – but is a humanly designed thinking apparatus and, as such, is subject to profound changes. Its first fundamental change was the introduction of zero in the late Middle Ages. Suddenly, there were no longer only natural numbers, but the space of real numbers opened up. In this new numerical space, numbers are no longer considered representatives of things, as they were in the past. Still, they are abstract points localized on a system of coordinates stretching like the arrow of time on a mechanical clock. Each number functions like an automaton, capable of producing all conceivable proportions: 0.5 yields a half, two-quarters, three-sixths, four-eighths – and so on to infinity—meaning it becomes a function, a mental Wheelwork. Take the trigonometric functions, which, following mysterious laws, all oscillate between 0 and 1 – which, perhaps, you remember, was always associated with the exclusion of zero—which is, of course, a ban on thinking. And what's hidden behind it is nothing more than the fact that Wheelwork logic was also absorbed by mathematics, where it was transformed into symbolic logic.

De Facto, the zero and one aren't really numbers but rather philosophemes, which have donned a kind of invisibility cloak with their numerical nature—philosophical masks, which, to the extent that they’re used unquestioningly without thinking, lead a form of dormancy, but in times of transformation emerge in a strangely transformed, metamorphosed form. This is precisely what happens with Boolean algebra – and because Boole sees this, he doesn't even try to mask it but argues as he thinks: as a religious mathematician.

The zero, he says, represents nothingness, one the universe – or, if you like being or non-being, presence, absence. But you could also say that one is the system, and zero is the system's edge. Boole's flash of genius consists in postulating that if you presuppose only this as invariant and immutable, everything can then be described in terms of how it relates to zero and one. This seemingly harmless thought marks a revolution: from now on, mathematics isn’t limited to what we consider mathematics, namely: the world of numbers in the narrower sense, but can refer to anything conceivable, whatever it may be, apples, pears, every Tom, Dick, and Harry. This can all be transferred into symbolic logic and thus become calculable—meaning it becomes mathematics. Take me, for instance. The universe without me, standing here, would, if an x represents me, be precisely defined by 1-x or 0+x. If we call my spectacles y, then x,y = me with spectacles. And so it could go on forever. Boolean logic can do what classical mathematics could only dream of because it’s no longer limited to quanta but encompasses the entire material world. This is the postulate of a universal algebra, which promises to convey a system that can mediate the whole world. This is no longer the narrow band of conventional mathematics, forced to reduce everything to quantifiable units of measure, number, and weight – but instead, it’s an enormous reach into the real world, an almost boundless expansion and transformation of what is called the ideal of mathesis. For now, every quality, insofar as it can be recorded as an x – meaning digitally, symbolically – is incorporated into mathematics. We have here, in mathematical form, the logic we experience on our computers because there, too, everything has become a description: a piece of paper only exists in the computer as a description of a piece of paper, and a character is nothing more than the description of a character. So you can say: Nothing is what it is anymore in the computer. But it can be reproduced as an x=xn at will.

And here I come to the second, highly remarkable point about this formula—put simply, it can be described as a detachment from things. The mathematician no longer asks what kind of X it is but only how it appears in the system of zero and one. The old question of identity has become obsolete. Instead, identity now results from a thing's location: from its networking linkages in the system. The question of thing X that we cannot know about has been silenced—abstracted from the world by the system's definition. It is a question that no longer arises, just as time has been silenced in the t of Newtonian physics.

This brings us back to this system's two main pillars, which Boole, not by chance, calls the nothing and the universe in a quasi-theological style. The emphasis, of course, is on the quasi. Naturally, the spicy part is that the noted zero is something other than death, and the noted one is something other than the universe. Strictly speaking, the zero is nothing without death; it might be called the information content of an obituary or the wisdom that says: one dies. Likewise, the noted one stands for a universe essentially designated as a complete, comprehensive thesaurus; therefore, it has to categorically exclude what, as a universe of non-knowledge, doesn't fit into this beautiful system, which the random function can beautifully exemplify. Because a coincidence taken into account is no longer a coincidence—this mental structure, whose static equilibrium is based on how the zero and one support each other, corresponds precisely to what we can call a digital system, or also as self-reflexive storage. Or, put less pompously: it's the logic of memory, the logic of the museum, the logic of the bibliography, of the critical apparatus. And so it's no coincidence, but rather an inner connection that the era in which Boole built his intellectual edifice also witnessed the construction of modern repositories: the great opera houses, the department stores, the libraries, the museums – the time when the world begins understanding itself as a storehouse. A culture seized by the furor of history begins organizing its inventory, taking notes, sorting, and indexing until its World corresponds to the ordered universe, as suggested by the Boolean logic of one—a universe structured like an encyclopedia where everything is listed, ordered, and interlinked. In this logic, its World tends to be ready-made, which means: closed. It’s not that everything worthy of being created has already been made, but in such a way that the systematics within and with which things are created and recorded no longer change – so, regardless of the distinction made between so-called open and closed systems, there’s an apparent affinity here to Cartesian thinking—with the only, but remarkable difference, that where Descartes reduced material nature to a dead Thing, digital metaphysics also reifies the mind.

Perhaps there are symbolic forms of death that describe a symbolic death. Take the form of death chosen by Alan Turing, another computer pioneer who made a name for himself as a mathematician, cryptographer, and designer of the decoding machine that deciphered the National Socialist encryption machine called Enigma during WWII, or, more precisely: who remained relatively unknown because of the classified nature of his work. After being loyal to his country for many years, he was arrested shortly after the war simply because his love wasn’t only patriotic but also for young men. When he, a hypersensitive, somewhat peculiar man, was released from prison after two years, he crawled away, socially compromised, into his own four walls—refusing all contact with the outside world. To die, he ate a poisoned apple – like Snow White. And so it seems he didn't really want to die, but—as in fairy tales—wanted to be laid out in a glass coffin and brought back to life by a prince happening to pass by – this symbolic death reveals more than just the awakening fantasy of an older, somewhat crazy homosexual; it brings (and this is what I want to get at) the fantasy connecting him (and us) with the computer to a concept.

The glass coffin is a reasonably precise symbol for the computer. Allow me to digress for a moment into the world of fairy tales – which I find appropriate, considering the computer world is also a kind of fairy tale world—or, as they say today: a virtual reality. So, what’s being conveyed in this picture? First, this coffin works like a freshness-retaining bag or a freezer because, as the fairy tale says, Snow White lies in it for a very long time and doesn't decompose. And then this prince turns up who, just by looking at this beautiful dead woman, falls hopelessly in love with her. Naturally, as we know from our psychoanalytic training, this is an extraordinarily strange look – precisely what Freud, in his usual dry manner, calls an object-occupation. Because this body is lying there as if dead, he's able to look at it calmly, like any other dead Thing. This look, which is one of domination like the anatomist's scalpel penetrating the body of the other – it’s a learned gaze from experience, which knows in the recognition process it must objectify, and thus kill, that which is to be recognized. In a sense, this gaze's fascination repeats the evil stepmother's intention to kill in fairy tales, with the difference that its destroyed nature attracts the prince; its symbolism—its lying in state in the glass coffin—becomes the object of his desire. As you will remember, the talk here is constantly about beauty, which means we're dealing with a projection surface that, like looking into a magic mirror, is about a symbolic body, about the observer’s phantasm. Because gazing into the glass coffin is also a mirror gaze, except it no longer reveals the prince-beholder's face but the face of desire. We can say that Snow White herself is the magic mirror, the symbolic body in which all the others recognize themselves. In this fairy tale form, we can discern something like a metaphor for scientific curiosity. So, that's the interest of denaturing nature and making the obscure object of desire into a lucidly illuminated one – of course, this fairy tale has a significant advantage over all our science stories because it tells of the energy our science apologetics conceal from us. And so we learn of the scientific gaze's necrophilia, we understand that this symbolic body's beauty has a dark, neglected prehistory – that we're striving to rid ourselves of nature as a foreign body we feel isn’t a part of us—that we learn of the fascination and the fetish character of the body that lies there in the glass coffin. We finally understand that our prince doesn't operate in the service of humanity but wants the object of his desire all to himself – insisting he can't live without seeing Snow White. This actually makes it clear that what drives him isn't the hope of immediately fulfilling his erotic desires but—in a highly charged, somewhat twisted turn—the possession of knowledge, the ability to look at the fetish object, not to mention all the experiments it allows you to perform...the outcome of which is well known. Because we're in a fairy-tale world here, where wishing promises to help bring the sign that's been destroyed back to life on a higher level – Snow White spits out her poisoned apple, and the Prince can celebrate his chymical wedding.

Here, in the form of a fairy tale, we have a small mythology of symbolic death—the death that every Thing endures when digitized. That's precisely the psychological effect the formula x=xn has on us. When something can be multiplied and potentiated at will, the individual loses meaning; it dies a symbolic death. Cryptographically encrypted, it enters the crypt of our thoughts. But this symbolic death, resulting from our experiencing the no-longer-individual as not belonging, is only the stepmotherly side of the problem, if you will—the other is represented by desire, as symbolized in the figure of our prince. Having become a pure symbol, we can now see the digitized thing in a new, unencumbered way. We can observe and analyze it at our leisure, thus seeing what we couldn't see in vivo. In this form, in this glass coffin of our knowledge, the beauty of this Thing becomes accessible to us – which is where the desire arises to bring this sign back to life, to re-animate it. The magic of animation: that it's possible to create a world made up of our minds’ fantasies – and against this background, it becomes clear what’s called analog-digital conversion isn't just a technicality but that the whole and highly symbolic secret lies here at the interface, as they say— because just as in the Snow White fairy tale it’s a symbolic death is at stake where we want to get hold of that glass coffin in which the object of our desire lies as if asleep, waiting for us to awaken it to life.

Keeping this in mind, it's clear the idea of the disappearance of things, which slowly is becoming a cultural-critical cliché, doesn't tell the whole story, but only its deadly beginning: the story of the poisoned apple, which, not coincidentally, conjures up the old story of Man’s Fall and its deadly knowledge. This story is also true, of course, and so we’re witnessing that things are no longer in their place, but they’ve fallen into the river, softened and half-liquefied, and seized by the Furies of Disappearance - all this is certain. But it is equally sure that, after we’ve fed them into the computer's glass coffin, they will suffer the fate of Snow White on another digital level—being resurrected and brought back to life. And my point is that this is part of a dialectical process of our perception. Seen in this light, the idea of the nature of things is the greatest fallacy of all, for it distracts from the fact that it's we who've given things the deadly gift, the poison, that it's we who've treated them stepmotherly, abandoning them as mere objects. So, to me, the talk of the disappearance of things often seems like a curse and an intentional desire to make things disappear from the new world emerging in the computer, an evil mirror glance that, for the sake of its own beauty, thus: of the familiar symbolic body, it would instead try to eliminate the new rather than accepting there could be something more beautiful than its own face, even if it were only in the distance, behind the seven mountains, with the seven dwarfs – of course, in the course of things—which is only the course of our own thinking—this is inevitable. And if we stop looking in the mirror and trust the past, we'll be able to see things in a new light. We'll realize that we're living in a transitional phase similar to that of the 14th and 15th centuries when people were most alarmed to see things losing their divine mark while they lost their language – just as the aureole of the sacred fell out of favor, so the aura of things, or rather: the aura of the fetish-object, will fall out of our sight. We will no longer be able to grasp a Thing as something we can bump into, something that has rough edges; we will no longer be able to understand it as nature, as a primordial rock that has fallen from another star. Things will no longer be definitive.

Only that which has no history can be defined (Nietzsche)

Perhaps it's this sentence we need to apply to the perception of things. What will disappear are those dark, opaque, and seemingly immutable objects—instead, we’re dealing with things in flux that are, perhaps, most precisely described as the non-things emerging with our Modern age: as radio waves and electromagnetic signals, in other words: things that are borderless, changeable and immaterial at their core. Unidentified flying objects (UFO’s), strictly speaking – and yet they've long been influencing our lives. Seen in this light, the term gutting also misses the point that we are and have been dealing with the fact that a spiritual core took the Thing’s material core—that things split into a material shell and a spiritual realm, into what we call hardware and software. This problem didn't only become a problem with the advent of the computer; it can already be observed in the music rolls of the early 19th century, in which the spurred roll is replaced by a punched card—which gives us the record player’s prototype. Unlike the conventional music rolls, the intelligence incorporated into things can now be detached from the material Thing itself; it becomes a punched card program, a sign, it becomes literature, or what we today call a program – it's precisely this shift and increase in abstraction that we're now seeing across the board. Strictly speaking, we should be speaking of a shifting core. The core of things, if it ever was, is no longer hidden in their material being but lies in their, or rather, in our intelligence, in the blueprint that precedes them – strictly speaking, we should be speaking of a shifting core – and so, with some justification, it would be possible to choose an entirely different approach, to emphatically welcome a new generation of things – digital, smart things that will keep pace with the times, that we can upgrade, beautify and provide with upgrades that allow for improvement where we previously only had to speak of a generational loss...we could welcome the spring of spirited things that can do the most incredible things...but even that would be, like looking into the mirror with the evil eye, and just as the prince is the other side of the wicked stepmother—it’d be a look that misses our own face, namely that it's we telling ourselves all these fairy tales.

Translation: Martin Burckhardt and Hopkins Stanley

Metamorphosen von Raum und Zeit: Eine Geschichte der Wahrnehmung, Frankfurt/M, 1994

Burckhardt, M. – Der Schatten der Dinge. In A lecture on apparatus and sound installation, Werkbund Archive, Renate Flagmeire, Ed. Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin. Jan. 1, 1995.

Burckhardt, M. – Digitale Metaphysik. Merkur, No. 431, April, 1988.

Strahlen translates both as the verb to radiate and as the noun radiance. Here, Ausstrahlen means: there is something emitted, something spent (as in ausgeben) in the process of radioactive contamination [Verstrahlens]; so you could say: when everything is spent, you realize the loss [die Verstrahlung] as what is radiated.

Twilight of the Mind

Twilight of the Mind: On the Disappearance of the Intellectual in Post-histoire is the third in our series of Martin’s later works. It was initially published in Lettre International’s 2016 Winter Edition – placing it between 2015’s Alles und Nichts: Ein Pandämonium digitaler Weltvernichtung

Digital Metaphysics

Martin’s labyrinth of thought began almost 40 years ago with a digital audio sampling device’s funny default naming scheme for sample files in a recording studio he was working in. This sampler’s programming algorithm asking what name to save the hybrid