We live in strange times. It almost seems we’ve stumbled into a never-ending witching hour, with ghosts returning we’d thought had long since finally been laid to rest. Take the phenomenon lèse-majesté [Majestätsbeleidigung]. If this lèse-majesté seems as bizarre and alien to an American as an unknown word, everyone in Germany knows what it means – even if this relic of the past feels as distant as being challenged to a duel. In the aftermath of the Böhmermann Affair1 (which broke out because a journalist had, not very elegantly, called the Turkish autocrat a goat-fucker), the classe politique proudly announced that the last remnant of the imperial lèse-majesté law was abolished. So far, so democratic. Times long gone, or so you might think. If only our political class hadn’t become so overly thin-skinned as to introduce § 188 of the German Penal Code [Strafgesetzbuch or StGB] overnight, thereby creating a criminal offense that revives the original crime in a new form. Since this accorded special protection to public officials, right down to the municipal level, you could speak of lèse-majesté without majesty – although, and this is surprising, the democratization of imperial immunity was accompanied not by a mitigation of the punishment, but by a pronounced intensification of it. It’s no wonder that the link to lèse-majesté was omitted from the reasoning behind this reshuffling, and something new was thought up as a kind of camouflage instead. Because the concept of Digital Sovereignty had already been introduced when the Network Enforcement Act [Netzdurchsetzungsgesetz or NetzDG] was established, it was easy to go one step further and equate criticism of political representatives with suspected hate speech. And so the first sentence justifying the law aimed at combating right-wing extremism and hate crime is as follows:

An increasing coarsening of communication can be observed on the internet, particularly on social media. More and more often, people are making general comments, but especially to socially and politically active individuals, in a way that violates applicable German criminal law and is characterized by a highly aggressive manner, intimidation, and threats of criminal acts. This attacks and challenges the general personal rights of those affected and the political discourse in the democratic and pluralistic social order.2

And because the authorities had opened up a big can of worms by invoking the emergency of the endangerment of our democratic and pluralistic social order, the political representatives were able to grant themselves a special right—more or less equating them with Democracy and protecting them from what had previously been called the Big Lout [der große Lümmel].

They sang the old song of Renunciation,

The Lullaby from Heaven

Which lulls when it moans,

The People, the Great Lout.

I know the Way, I know the Text,

I also know the Master Authors;

I know they secretly drank Wine

And publicly preached Water.

(Heinrich Heine: Germany, a Winter's Tale)

Michael Much, a Bavarian entrepreneur who, probably after watching one too many talk shows, had become very annoyed, received a lesson in how this law affects the ordinary citizen. Because he’d wanted to express his displeasure with the Green leadership and – after having found a series of witty statements on the internet – he took action by putting up two large-format posters in his garden in September 2023:

The poster on the right is a depiction of Cem Özdemir, Ricarda Lang, Robert Habeck, and Annalena Baerbock with captions translating as: ›We’ll flatten everything,‹ ›Alliance 90 Green Shit,‹ and a Robert Habeck quote ›Patiotism always made me puke. ‹ On the left is Robert Habeck with his quote ›Companies don’t go bankrupt, they just stop producing.‹ over the caption: ›Can he even count to 3?‹

The result: a few weeks later, on October 25, 2023, the police arrived at Mr. Much’s property – and although the corpus delicti was visibly displayed on the entrepreneur’s private property, they didn’t leave it at a warning but searched his house for further evidence. The background: Because the entrepreneur didn’t want to admit that he’d put up the posters himself, and because it had been discovered he’d installed video surveillance on his property, they wanted to find out who had put up the posters using the confiscated video material. When confronted by the authorities, the good man confessed, admitting he’d put up the posters. So they confiscated the posters and left. A few weeks later, a letter from the Munich II public prosecutor’s office fluttered into the house, imposing a fine of €6,000 on the entrepreneur for violating §188 of the German Penal Code—the reintroduced »lèse-majesté paragraph.« The most intriguing aspect of this was that Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock herself had signed the criminal complaint that set the proceedings in motion – a thought which seemed almost inconceivable to the entrepreneur, who, when confronted with this fact, was convinced the signature could only be a forgery. But that wasn’t the case at all. The only plausible conclusion was the Foreign Minister’s graphical representation, which depicted her as a pouting but not an unpleasant, defiant head, led her to put her royal Wilhelm, no, her royal Wilhelmine, under the criminal charge. Looking at the posters, you wonder what exactly is so defamatory and libelous about these statements. Apart from the rhetorical question and the title, which is a put-down of the character, these are literal quotations of the people in question – nothing that could even come close to equaling Böhmermann’s ›Goat Fucker'.

If we compare this with a Swedish case that came to light in 2012, we see the sensitivity is even more striking. In that case, counterfeit one-krona coins were put into circulation bearing the words »Our Whoremonger of a King« instead of the official inscription »Carl XVI Gustaf, King of Sweden« – an action that didn’t result in either a lawsuit or court proceedings.

It becomes apparent here just how thin-skinned Germany’s political class is today when comparing the ›insult against majesty without majesty‹ with the old insult paragraph (§ 185), which has been reserved for commoners since the days of the German Empire and adopted almost unchanged into the penal code. The latter provided for a fine or prison sentence of up to one year, while a violent insult, such as a slap in the face, could result in an additional year’s imprisonment for assault. By contrast, § 188 really brings out the big guns:

(1) If a person who is active in the political life of the people is publicly insulted in a meeting or by disseminating content (§ 11, Section 3) (§ 185) for reasons related to the position of the offended person in public life, and if the act is likely to significantly impede his or her public activities, the penality insult shall be imprisonment for not more than three years or a fine. The political life of the people extends to the municipal level.

Under the same conditions, defamation (§ 186) is punishable by imprisonment from three months to five years and slander (§ 187) by imprisonment from six months to five years.

Quite obviously, § 188 links the defamation paragraph3 with the issue of hate crime, which is attributed to a far greater degree of punishment than a slap in the face. And because the protection of people in the Nation’s political life has been extended to the entire political caste, right down to the local level, we’re dealing with a political privilege here. Shrouded in the maiestas of Democracy and the Common Good, they were categorically distinguished from ordinary mortals by virtue of their office – which Wolfgang Kubicki, with a nice flippancy, formulated like this in reference to Robert Habeck: he probably believes that »he is the anointed one.«

While they may act as the legally certified defenders of Democracy, their thin-skinned nature reveals that they’re more like the Modern Age’s royal children. In any case, the representatives’ zeal for prosecution is so great that it far exceeds the number of Imperial lèse-majesté proceedings. While these amounted to 12,000 charges in the thirty years from 1888 to 1918 by far, Robert Habeck was able to register 805 criminal charges within the year, with Annalena Baerbock mustering another 497 – an activity resulting in more than three times the number of imperial injuries by these two politicians alone.4 This behavior reveals the same self-empowerment logic already articulated in the concept of Digital Sovereignty. Delving into legal history, the crimen laesae maiestatis—the crime of lèse-majesté—goes back to antiquity – referring to actions directed against the polis as a whole: in other words, a conspiracy to overthrow the State or high treason. Because power in Rome was privatized, the Roman emperors from Tiberius onwards transformed immunity into an imperial privilege – punishing offenses against the Emperor, his family, and his privileges with the death penalty. With the lex Quisquis of Arcadius in 397, even the mere intention to commit a crimen maiestatis became punishable – and imperial officials were also granted the immunity of their ruler. While lèse-majesté—the crimen laesae maiestatis—could be understood as a protective mechanism of an existing order, indeed of a secular reign, a profound reinterpretation occurred in the Middle Ages. Pope Innocent III added a crime against divine order to the offense against the secular order, namely heresy – thus anchoring the offense against majesty as an offense against God in canon law. Because secular rulers were subsequently regarded as being anointed as God’s representatives on earth, the German jurist Benedict Carpzov, the Younger (*1595 – 1666) was able to interpret the verbal, and even more so, the physical attack on the Sovereign as an offense against the heavenly order. This context is interesting insofar as Carpzow was primarily known for his Practica nova Imperialis Saxonica rerum criminalium and his Peinlicher sächsischer Inquisitions- und Achtsprozess [Exhaustive Saxony Inquisitions and Eight Process]—leading a 19th-century scholar to call his legal œuvre that of a Protestant Hammer of Witches or Malleus Maleficarum. This terrible jurist’s thinking is teeming with terms such as devil’s bride, damage magic, and the like. Consequently, Carpzow was deeply convinced of the devilish arts’ reality – and as a pedantic jurist, he believed that a pact with the devil deserved only one punishment: death by fire. In any case, Carpzow ruled that verbal and, even more so, physical attacks on the Sovereign were the worst crime of all. Given this history, lèse-majesté takes us back to genuinely dark times – and we can be thankful that in the German Empire, only the emperor could claim such a privilege.

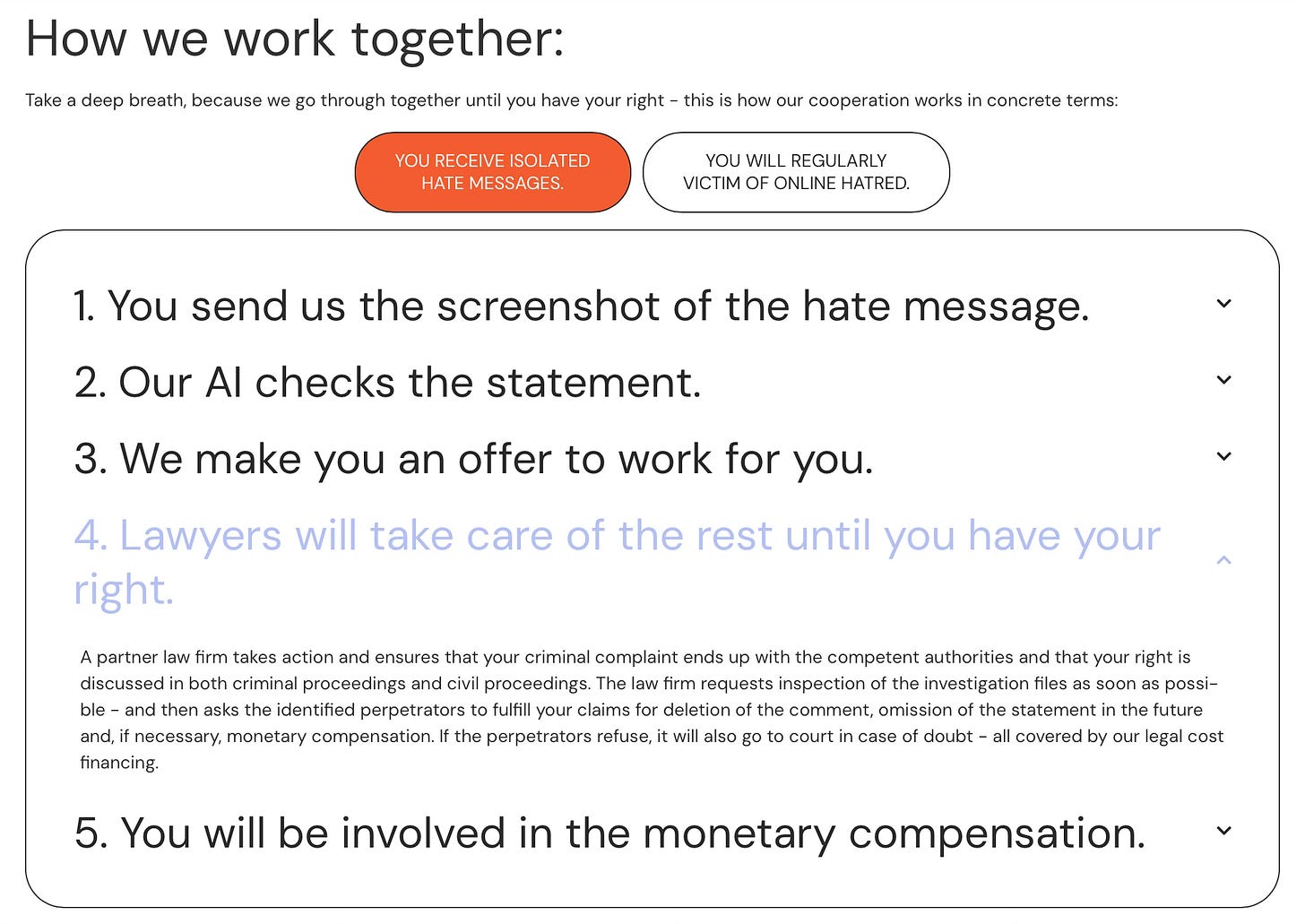

Now, it’s evident in the eloquently demonstrated repealing of the old lèse-majesté law following the Böhmermann Affair – that while §188 may be dealing with a ghost carrying a heavy historical burden, its new guise is a different matter. It’s no coincidence that the paragraph has been cloaked in a highly civilized order – and people never tire of claiming that, in the end, it’s only a matter of protecting Democracy from its despisers. Now, the legislators of the law may act like true constitutional patriots to combat right-wing extremism and hate crimes, but the metaphysical Nazi conjured up here makes it clear they aren’t necessarily operating in the realm of political reason but in a chamber of horrors bearing similarities to Carpzow’s world of thought. Even more disturbing than the belief in the casting of curses is a legal fact that, insofar as it grants a special right to an entire caste, overrides the basic idea of isonomia – that is Equality before the Law—which is the same short circuit used in the case of Digital Sovereignty. As in the case of Digital Sovereignty, the privilege of the collective entity – namely, the protection of the common good – is delegated to an individual—in other words, it’s privatized. Consequently, every local politician, even the mayor of a 100 Souls parish, is now considered an anointed one who can ward off the hostilities of internet plebs under this law. Considering in the internet’s early days that politicians gained political capital by acting as a grassroots democracy, even as a political grassroots movement, the oddity now is that profiteers of this movement are all up in arms about this World’s consequences—that everyone [jedermann*frau*divers5] now has a voice, that the logic of representation is over, and the old elites are history. That their remedy is seen as pretending to be a king’s child of the Modern age with its corresponding level of insults running grotesquely counter to everything maiestas originally sought to protect. How problematic this becomes is apparent when the number of insults are often seen as badges of honor, one with which a politician assures their reputation. Consequently, it’s no wonder backbenchers like Helge Lindh have distinguished themselves in the fight against internet hate speech—while attention-desperate politicians instigate such actions themselves – such as the Erkelenz councilmanManoj Jansen, who sent himself razor blades by post and smeared his doorbell label with a Swastika. Comparing this inverted narcissism, sustained by self-victimization, with the defamation of the 19th century when combatants went out to a duel at dawn for life and death, the change in manners is noticeable – and it doesn’t only go back to the verbal insults of Internet users. The extent to which politicians’ sense of honor has to do with the Attention Economy and the present’s digital operating system is evidenced in how the alleged crimes’ prosecution has long since become a business model in which classic character defamation leads to an automated warning behavior. This is precisely the SoDone company’s business model that promises AI-augmented tracking of political opponents under the heading Stop online hate. The three-person company’s story is simple. A young Oxford student of European politics has a housemate write software that »searches publicly accessible comments in social media for relevant statements about the person to be protected.« And because this bot holds the promises of a very cost-effective solution, a business model quickly emerged—especially since it was possible to count on such a highly receptive political environment. Consequently, this start-up took third place in the North Rhine-Westphalia Start-up Competition, winning €10,000 – and was soon counting Minister-President Hendrik Wüst, European Parliament member Marie-Agnes Strack-Zimmermann and Robert Habeck among its clients. Given that both Prime Minister Wüst and Robert Habeck allowed themselves to be used as advertising media for these lèse-majesté lawyers suggests a robust, even ataraxic, understanding of their office.

Even though the company has since been issued a cease court injunction from doing this, it hasn’t changed the slightest thing about the company’s business model. Consequently, the AI-augmented warning machine is still at work – and, armed with a familiar and friendly tone, invites the public to feed it with suitable material:

That anyone would believe an AI could reliably vouch for defamation—thus believing they could advertise with it—shows how far the concept of honor has drifted from the person into the actual Android realm, where it’d be much more appropriate for this bot to take on not humans: but other bots. On the other hand, the inequality of its arms program is its methodical madness. And because politicians can be held up as Advertisement exemplars who don’t themselves pay for their libel suits – but at the State’s expense, the company advertises that the complainant doesn’t take any financial risks. That success, should it arise, can be split equally.

If the offender has to pay monetary compensation, you will receive 50%. We use the other 50% to finance our company and to conduct further lawsuits. You will receive a share of the proceeds if the case is successful. If there is no monetary compensation but costs are incurred, we will cover these for you. [Translation: Google Translate]

The consequences of such practices in everyday life were experienced by pensioner and former Bundeswehr soldier Stephan Niehoff, who made the mistake of redistributing a Twitter feed containing an advertisement variation of a joker replacing the company brand name Schwarzkopf with Schwachkopf [Moron] and placing an image of our tousled-haired economics minister above it. Because Robert Habeck felt that his political work had been impaired by this retweeting by Niehoff and his 175 Twitter followers, he signed the administrative order and police gathered in front of Niehoff’s apartment door at 6:15 AM, equipped with a search warrant from the Bamberg public prosecutor’s office, demanding entry. The Schweinfurt police press release stated:

On account of this „suspicion of defamation directed against persons in political life in accordance with §§ 185, 188, 194 of the German Penal Code (StGB),“ a search of the accused's apartment was carried out by police officers from the Schweinfurt Criminal Investigation Department last Tuesday, November 12, 2024, on the orders of a judge. During the search, a tablet belonging to the accused was seized.

What the confiscation of his technical device was supposed to achieve was unclear. After all, the former Bundeswehr sergeant wasn’t even the author of the post in question, but only the person who had found it funny enough to share. However, the effect of such actions is far more important. As Mao Zedong put it:

Punish one, educate a hundred!

While it’s questionable whether this strategy really works, Habeck’s Moron-gate will probably become a reliable companion to his political career.

There isn’t any doubt that social media makes it easy for people to give free rein to their baser human instincts. When all it takes is a click to invoke a digital invisibility cloak of protection for expressing yourself as you please freely, it’s no wonder communication forms are emerging that would be unthinkable in a face-to-face situation. What’s been proven with this blurred legal concept of hate crime is that its flip side is still being loudly celebrated: That—unlike under the conditions of representative democracy—everyone now has a voice. In this sense, today’s digital operating system works towards what we appreciate as a rhizome, a grassroots movement, or a grassroots democracy. However, instead of acknowledging the political sphere’s shift, these political representatives use their new wishing machines – only to turn around and complain in the same breath that their political opponents are using the same method against them: Protect me from what I want! That in these circumstances, lawmakers would resurrect the 19th century concept of honor to decree something like a digital sovereignty in the world of dividuals testifies to a profound blindness to the present. No, it’s far worse! In the name of protecting the polity from the Internet World’s brutalities, the People’s Representatives have enacted measures that are assaulting Democracy itself. Because by according special protection to the State’s Representatives, the isonomia, or equality of all citizens, has been damaged:

Equality before the Law –

which, according to Herodotus, is Democracy’s most noble hallmark and distinguishing characteristic. In ancient times, this was ensured by writing the Law and thus sacralizing it – with the result that even rulers were subject to it. In this context, Capitalism’s new digital operating system marks a shift in the political realm – from the Alphabet to Coding, from the letters of the Law to a liquefied order that’s still searching for its appropriate institutions. Political thought, however, which has assumed the right to pass judgment on all conceivable thought crimes by claiming the right to Digital Sovereignty, is heading precisely in the opposite direction. By posing as the controller of the intellectual operating system, it sacrificed the respect that the ancients commanded for the written word to a lust for power. From here, it’s understandable how and why Carl Schmitt, of all people, was able to become Digital Sovereignty’s prompter – after all, he decreed that sovereignty consists of being able to rule because of a self-declared State of Emergency. And it’s precisely this State of Emergency that’s been declared now that all manner of hubris can run riot below the criminal liability threshold. When people endowed with such power act like Modernity’s royal children, when narcissistic humiliation transforms into concentrated resentment, indeed, a veritable mania for prosecution, the citizen has mutated into a virtual werewolf, into homo homini lupus.

When the wonderful anthropologist Mary Douglas saw the hallmark of civilization is that you can’t be convicted of what you have done in the dreams of others, the question arises:

Could it be that we are moving back into dark times?

Ps. The company SoDone, or its lawyer Brockmeier, has meanwhile been prohibited by the court from offering its services for free with the threat of a fine of € 250,000, as such »unfair legal advertising promises and advertising offers« are contrary to the law governing the legal profession.

Translation: Hopkins Stanley and Martin Burckhardt

After a Turkish autocrat was referred to as a Ziegenficker [goat fucker], §103 of the Strafgesetzbuch [Penal Code], which had been abolished as it no longer referred to the native head of State but to foreign potentates and threatened a prison sentence of up to 3 years for their insult, and in the case of a defamatory insult, a sentence of three months to five years. The unanimous opinion was that this paragraph, a variant of the imperial ›insult to majesty,‹ came from a time that we’d left behind politically, morally, and intellectually and was antiquated from today’s perspective and should, therefore, be abolished. The Bundestag complied, and on June 1, 2017, it was unanimously decided to abolish § 103 of the German Criminal Code; this came into force a year later on January 1, 2018.

The frontrunner in this field is FDP politician Marie-Agnes Strack-Zimmermann, who files more than 100 monthly criminal complaints.

The German term jedermann*frau*divers, sometimes called the Third Option, loosely translates something like every Woman, Man, and Diverse Other. It’s a language-policing attempt to make the German language gender-inclusive, which humorously results in great confusion for general native speakers.

Related Content

Downwards!

When we speak of totalitarianism, we often conjure up this image of an all-powerful, fearsome state: a portrait of the Leviathan, drawn as a monster! Franz Neumann, the unfortunately forgotten political scientist, provides us with a structural analysis of Nazi rule that brings a very different perspective into relief – one that’s extr…

Postmodern Demonology

If, when reflecting on the fatalities of today's culture wars, with its encroachments and infringements by self-appointed language police, we're reminded of George Orwell, of his logic of Oldspeak and Newspeak, thoughtcrime and the Ministry of Truth, it's no coincidence. Like few others before him, Orwell grasped the abysses of totalitarian thinking. He…

The Bill of Identity

The following open letter addresses the German Self-Determination Act. Although based on laudable intentions, it does have a few oddities or identity traps that are humorously pointed out. This form of legislation is not unique to Germany, but is globally en vogue (or should one say: