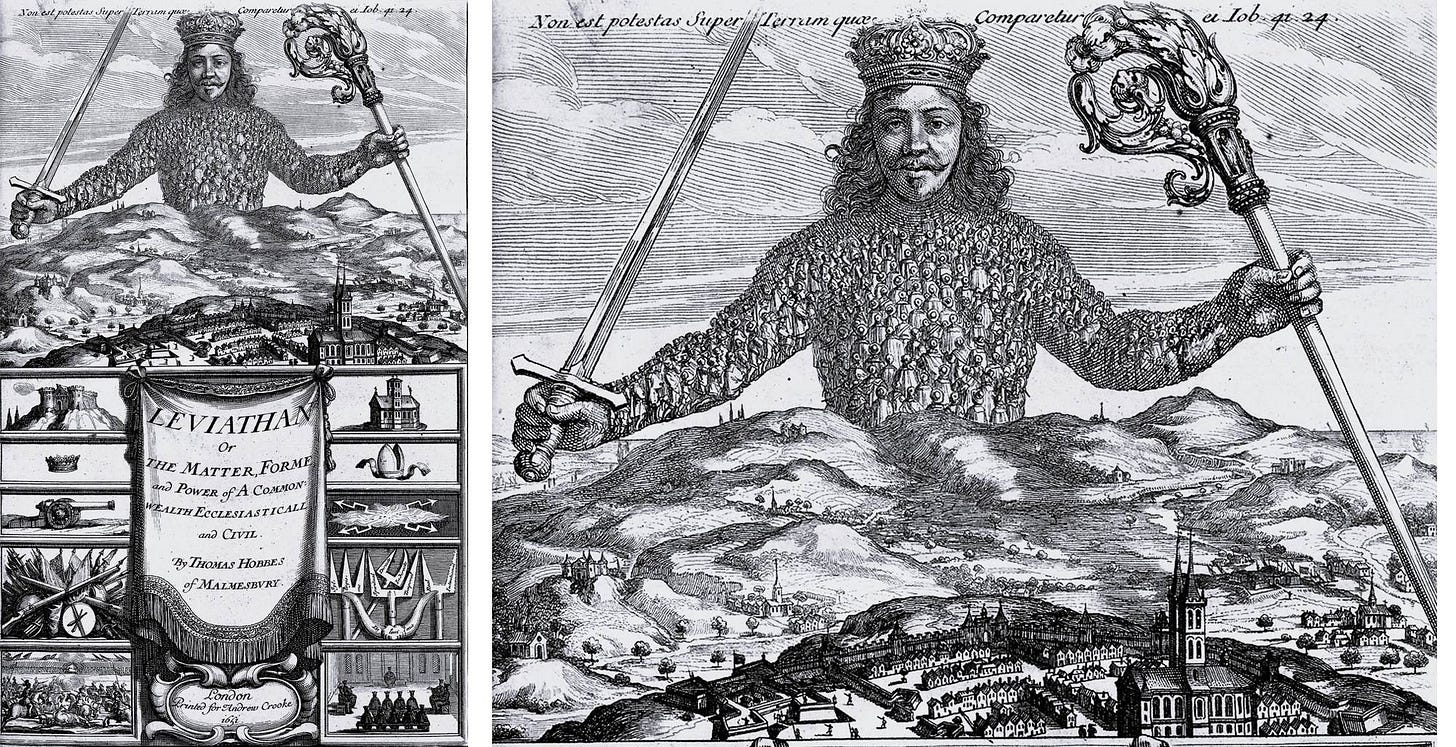

When we speak of totalitarianism, we often conjure up this image of an all-powerful, fearsome state: a portrait of the Leviathan, drawn as a monster! Franz Neumann, the unfortunately forgotten political scientist,1 provides us with a structural analysis of Nazi rule that brings a very different perspective into relief – one that’s extremely helpful for understanding contemporary forms of totalitarian thinking.

Neumann didn't understand National Socialism as a form of State deification but as an attack against the State – which explains the title of his 1942 book, whose title is Behemoth, named after the Leviathan’s adversary. It's clear this assessment wasn't just pulled out of the air if you consider remarks made by Hitler, who declared the German state to be merely a tool and preferred the Movement—»The state is not our master, we are the masters of the state.« Just how pronounced this instrumental view was—and just how great Hitler's contempt for the rule of law was can be seen from the brutality with which he undermined the institutions of the young democracy. His promotion, and even more so, his mastery of institutional ambiguity, was particularly successful in this campaign against the rule of law. Because Hitler, as a Social Darwinist, deeply believed in the survival of the fittest, he systematically blurred institutional responsibilities. As an exemplar, Adolf Eichmann's ›Jewish Department‹ had a rival department set up alongside it. The result was that competing institutions outdid each other in their efforts to please the Führer – and because creativity became a critical factor in this game, constitutional requirements became bothersome constraints that players could boldly discard. If this form of an early Attention Economy2 had an effect, it was that the meticulous and predictable State-owned enterprise was no longer the uncontroversial master of events—instead, a shapeless monster took its place in a way that allowed the fiction of the rule of law to be maintained externally. Factually, however, the institutional reconstruction began, leading to the personal rule later called the Führer state. Its devastating impact is vividly illustrated through a story related by Wolfgang Sofsky in his book The Order of Terror3. In the concentration camps, prisoners weren't allowed to walk around without their caps. If a guard took it from the prisoner and threw it over a line that the inmate was forbidden to cross under penalty of death, the dilemma was unavoidable. After all, what was the prisoner to do when the guard mockingly reminded him he was walking around without a cap—and that he should kindly pick it up? Because it was clear to him that another guard, whose job it was to monitor the uncrossable border, would shoot him on the spot, in either case, he was dead – and the two guards who had agreed to this perverse game of killing could persuade themselves they had only followed the laws and that the murder of the prisoner was, therefore, legal. While the exemplum may be drastic, it makes perfectly clear that obscuring and instrumentalizing the laws and institutions necessarily results in arbitrary rule, ultimately in a regime of terror. In any case, we fall short if we understand the Behemoth merely as a synonym for the civil war—as a bellum omnium contra omnes—thus disregarding the possibility that a formally maintained constitutional state can also turn into just such a monster.

Now, it'd be easy to take comfort in thinking the Führer's excesses of State are a thing of the past, just like Stalinist rule. But it is easy to forget in this context that the underlying problem is by no means overcome: namely, already, the moment a given order is reduced to a mere instrumental order, the spirit of the laws becomes subject to the arbitrariness of those in power. Considering the significance of Movements for contemporary political discourse, it's conspicuously evident that totalitarian thinking is celebrating its revival in many a postmodern guise. The proclamation of Civil Society at the millennial turn was a structural vote of no confidence in the Leviathan – and proof that the Student Revolt Movements had marched successfully through the institutions. In any case, the universally celebrated Civil Society gave rise to a new classe politique, assembling various front-line organizations seeking to influence politics in their own interests. This form of lobbying was highly successful because the activists could give the impression of wanting to help achieve noble goals – whereas traditional Statehood was subject to general suspicions of toxicity. However, this overlooked that moral grandstanding brought the individual a gain in moral prestige that could be converted into a financial advantage—porkbarrel [Staatsknete4] in the vernacular. To the extent and degree that civil society movements took over state positions of power, their companions were, in turn, provided with sinecures, creating a revolving door effect in which people moved from the Ministry to an affiliated organization and vice versa. The policies of the past decade show the fatal consequences of this political gray area. An early and particularly questionable exemplar in this context is provided by former German Justice Minister Heiko Maas, who pushed through the Network Enforcement Act (NetzDG) in 2017. Autocratic Russia very soon copied this for its political usefulness, a process that Christian Mihr of Reporters Without Borders commented on as follows:

Our worst fears have been realized: the German law against hate speech on the internet is now being used by undemocratic states as a template for restricting social debate on the internet.5

But the Russian copy wasn't an abuse; it was just a logical continuation of the dark logic of self-empowerment that had already been revealed in the law's drafting. To warm up public support for his legislative project and give the initiative the appropriate fig leaf, Heiko Maas gathered several intellectuals around him. Using the human rights charter as a model, they drafted a charter that boldly added corresponding data protection rights to human rights. Strangely enough, the authors weren't afraid to paraphrase the teachings of the Third Reich's crown lawyer, Carl Schmitt, in one of the early versions. While the latter decreed that the sovereign is the one who declares a state of emergency, one of the first sentences of this questionable piece of work claims: „Sovereign is he who has control over his data.“6 While, for psychological reasons, Data Sovereignty [Datensouveränität] may be a thoroughly understandable desideratum comparable to the protection of privacy, the conceptual use of sovereignty here is far more problematic. This already applies to how Carl Schmitt used—no, even abused—the concept of sovereignty. By making sovereignty a speech act, the figure of the Leviathan was handed over to the decision-making of a single person. From a structural point of view, this denies that the Leviathan's emergence isn't the intellectual creation of a philosopher but refers to a collective person. This is why Thomas Hobbes didn't justify the State rationally but gave the Leviathan and Behemoth equally mythical origins. If Hobbes conceived of his Leviathan as a mortal god and a Machine—as a Wheelwork automaton [Räderwerkautomat]—it's because here we're dealing with a being bearing no resemblance to any living figure.7 From a historical perspective, the Leviathan, articulated in philosophical thought and then in the form of the emerging Nation-States equipped with Constitutions and Central Banks, could be understood as a pacification measure.8 In any case, the State ended the continuous religious and civil wars of the late Middle Ages and the Modern Era because the State's monopoly on the use of force ensured that man no longer needed to be a man's wolf.

Having brought this into focus, we can see Schmitt's privatization of sovereignty represents a level break—and how the phantom of data sovereignty is a reflexion of further radicalization. Thus, power is now being granted to individuals to an extent previously reserved for the political community.9 Now, part of data sovereignty's paradox is that it was decreed just as the government agencies saw themselves unable to enforce it—a phenomenon that also applies to the EU's Digital Services Act. This dilemma was beautifully described when a politician commented: ›The Americans know how to handle data; we know how to handle data protection!‹ Here, we could speak of self-empowerment in the face of a proven impotence. Yet its consequences were exceedingly delicate because the Net Enforcement Act [Netzdurchsetzungsgesetz] led to the State’s deputizing social platforms as auxiliary law enforcement officers obliged to carry out its judicial and executive tasks under threat of horrendous fines. Indeed, this outsourcing of state authority has more than problematic consequences because—to avoid penalties—the internet companies went overboard – as the Corona-era censorship measures eloquently attest.

Since this act, which in legal terms represented a bursting of the dam, outsourcing State sovereignty in the form of rights and duties has become common practice. In the State's shadow, lucrative business models have emerged benefiting both officeholders and beneficiaries—but ultimately leading to the acceptability of totalitarian thinking over á la longue durée. Insofar as a government department can rely on an affiliated apron organization (with the appropriate funding) to act in its interests, there's no need to worry about such organizations exceeding their authority. If lobby organizations develop an inappropriate zeal, and once institutional irresponsibility has been established, politicians can excuse themselves by saying they have nothing to do with it. Conversely, the organizations living off State aid are careful not to endanger the sovereign sympathy, ensuring their livelihood. And because there's always a kind of competition here, structurally, you have a situation similar to that described by Franz Neumann in his Behemoth. Because everyone is trying to please their sponsor, a bidding war has been launched, giving the movement additional momentum—always at the expense of the rule of law—while the ruling politicians' advantages are obvious. Since this form of public relations work has corresponding repercussions, its results can be exploited politically and propagandistically. When the government, with the active assistance of Correctiv, various reporting centers, and trusted flaggers, spreads all kinds of conspiracy theories, it's easy to celebrate itself as the incarnation of the democratic rule of law, ceremoniously authenticated by the hundreds of thousands of demonstrators lured onto the streets by fabricated skandalons. The transgressions people feel empowered to commit demonstrate that politicians have noticed this form of mass mobilization. When the State's delegitimization, like expressions of opinion below the threshold of criminal liability, are declared ›endangering the State’s welfare‹; when a politician with Anton Hofreiter’s clout demands journalists show more humility towards those in government; when hate and agitation as ›thought crimes‹ become criminal offenses—this testifies to nothing less than the incursion of totalitarian thinking not only on the fringes of society, but in the institutions themselves. True to their jingoism, »The state is not our master, we are the masters of the state,« they generously ignore the spirit of the laws. If we’re blessed with a sense of oblique historical comparisons, we might think that the barbarians haven't besieged the gates but made themselves comfortable in the offices. In any case, the slippery slope attributed to the totalitarian state—to the Behemoth—has been taken.

Translation: Hopkins Stanley and Martin Burckhardt

Franz Neuman was a German socialist thinker who became a political scientist. He studied under Karl Mannheim at the Frankfurt Institute for Social Research, fleeing with him to London after the Nazis assumed control before moving to New York. He is often considered part of the Frankfurt School.

It's often forgotten that the Society for Consumer Research, which provided TV ratings in the post-war period, was founded in 1934 – an organization that enjoyed the support of the National Socialists. As its chairman, Wilhelm Vershofen announced, the Society’s aim was »to make the voice of the consumer heard.«

Sofsky, W. – The Order of Terror: The Concentration Camp, trans. William Templer, N.J., 1996.

Staatsknete [Governent Dough] was coined by Renate Künast, where Knete in German vernacular is a gangster word for money– so the term implies a way of robbing the State similar to political Pork.

Evidently, the embarrassment of this became clear, because this formulation has disappeared in the revised version. Nevertheless, the idea has found its way into our vocabulary and thinking in the form of ›Data Sovereignty.‹

In this sense, we have an institutional counterpart to what I've termed the Alien Logic.

A clear exemplar of this privatization trend is the 2006 Environmental Appeals Law [Umwelt-Rechtsbehelfsgesetz or UmwRG], which allows associations such as the German Environmental Aid [Deutsche Umwelthilfe] to file lawsuits using the German Association Action Act[Verbandsklagegesetz], not in their own name—but in the name of the general public. As such, small groups could elevate themselves as representatives of the general public – a logic of self-empowerment inscribed in environmental activists' actions.

Alien Logic

The following is the visualization of a lecture Martin gave on May 11, 2021, at Vienna's IWM, where he spent a few months as a fellow in the spring following the publication of the Philosophy of the Machine. Because this lecture is a tour de force pulling together his previous thinking as a prequel to his five-book series, the

Talking to ... Catherine Liu

Imagining the Boomer world straying into suffocating moralism during the Pop Revolution would have seemed like a grotesque, if not outright ridiculous, mind game. Actually, it is a first-order puzzlement how such a terror of virtue could take hold of our political discourse and institutions. It is precisely this question that cultural theor…

The Neoliberal Wokistan

This short text may seem counterintuitive, even perhaps as a mental aberration. After all, what do our ›Woken‹ world saviors have to do with the Wall Street Wolves? In following their self-image, we see how they’ve taken an anti-capitalist position, claiming that our social system is exploitatively toxic. From this perspective, any notion that these zea…