Why I have a protruding Ear – and still don't want to have it corrected [Warum ich ein abstehendes Ohr habe – und es nicht richten lassen will] was a lecture Martin gave at the Protestant Academy of Tutzing’s symposium on Hearing and Servitude [Gehör und Hörigkeit1] on March 3rd, 2000, shortly after the publication of »Vom Geist der Maschine«.2 Here, he draws on his many years of practical experience in sound studios to discuss how the prevailing doctrine, known at the time as »the Visual Turn,« didn’t fully address the ongoing cultural rift. In it, he explains how the shift in perception from the Digital Order is disrupting our Social Drive [Gesellschaftstriebwerk] as a perceptual shift from relying on the Eye to the Ear—marking a move away from the Central Perspective’s Logic of Representation, with its subject-object split, or more generally: the transformation of our worldview from representation to simulation.

Hopkins Stanley

Why I have a protruding Ear -

and still don’t want to have it corrected.3

Ladies, Gentlemen,

You can say whatever you want about my lecture, but as far as the first part is concerned, you can't accuse me of not telling the truth. Naturally, this is a great advantage: I will not be discussing an »imaginary« [eingebildet] flaw but a very obvious one.

On the other hand, there is a certain dilemma here: if you are willing to go on the offensive, you might also imagine a flaw as something to be proud of – which would then be a second-degree conceit, resulting in the paradox that the Ear is also suitable for »Imagination« [Einbildung].

And I believe that was the fear I secretly held about my lecture’s title: that it would soufflate the now popular ›politics of the senses‹ to criticize video art as if it were a great, all-listening ear. As if hearing were the deeper, nobler, more intimate sense, in which case the solution would be to be all Ear. Now, there are undoubtedly significant differences between practices of the Eye and the Ear—and these differences will be the subject of the following discussion—but these differences are not inherently Natural, but rather the result of historical techniques. Broadly speaking: it’s only sinceCentral Perspective’s image-processing machine has enforced the primacy of the Eye that we have been dealing with the visuality of modern times, the parameters of the overview, the view through, the nexus of viewpoint and vanishing point, horizon and perspective. Leonardo da Vinci seriously considered exchanging one sense for another – that, if it came downto it, he’d give his Ear for his Eye. You could say Modern Philosophy is fundamentally panoptic from the ground up. When Philosophy and political thought resorted to metaphors of the Eye, it wasn't really the eye itself that was intended, but primarily its technique: Subject/Object, the way we position ourselves in front of a frame and form our World-View[Weltbild]. We encounter not nature's innocent, unarmed gaze here but a highly armed, complex projection device: a Worldviewing Machine [Weltbildmaschine].

What's more: I can easily imagine that someday, perhaps in a hundred years, the most advanced Worldviewing Machine will no longer operate panoptically, but panacoustically – where words such as vibration, overtone, noise, or the like will take on a peculiar meaning. In a sense, this is already foreseeable—or rather, I should say: audible—because navigating through the knowledge space can no longer be fully grasped at through graphical interfaces alone. From in front of the screen, you no longer see what the underlying space truly is – only the glowing surface, not the structures behind it. To understand how this realm of hidden strata and surface creation works, it’s necessary to traverse the layers and grasp their logic.

Here, the advantage of hearing becomes clear: unlike in the optical realm, where one element always obscures another, the layering process is more easily and accurately understood in the acoustic domain. When a voice is added, it doesn't necessarily have to mask another – we have this unique ability for polyphony. Acoustically, what is impossible in physics, as stated by the Pauli exclusion principle, is possible: that two things can occupy the same space at the same time. This absurdity in the development of physical theory has long been a reality for us: protruding from remote realms into our immediate environment – and even when we're not staring at our computer screens – we are dealing with overlapping spaces. – What we hopelessly and anachronistically call the here and now mingles with an anytime, anywhere. Because we hold a remote control and a REPLAY button, different layers of space and time overlap in ways that would have been unimaginable not long ago.

But how do we grasp these spaces? Visualizing the layering of multiple spatial and temporal dimensions, mathematically known as n-dimensional space, is virtually impossible. Nonetheless, this space can be heard. Our visual field doesn’t restrict our hearing; it includes what is happening behind us, above us, and below us. It is no coincidence that the ear is the seat of our sense of balance as an organ of positional awareness. This is a crucial connection for me: as spatiality becomes more complex, the Ear is destined to become the primary medium of the future, and eventually, we'll be discussing sonification instead of visualization. Of course – and this is the purpose of all these preliminaries: if one day thinking becomes panacustic, we won't be confronting Nature either, but a sophisticated apparatus. People will be just as proud of these devices as they are today of optical ones. When I talk today about the Ear as a source of shame, it's not because the ear is naturally such a thing, but because, under the conditions of Presence-of-mind – the conditions of a highly visualized, visually stylized society.

What is this strange connection – the Ear and shame? In terms of overall body symbolism, one could argue that we are consistently feminized by hearing because we can't avoid being exposed to all sorts of penetrating noise, and thus, nolens volens, we often exhibit the openness often ascribed to women. However, it is questionable whether the prognosis of the future will be obedient [hörig] and feminine is particularly helpful. In fact, the equation of shame and Ear has a long and complicated history. If you look back into Christian dogma’s history, you discover—and this is crucial for the Dogma of the Immaculate Conception—that Mary conceived her child not through her womb but through her ear: Ear conception. Here, shame has gone to her head—ceasing to be shame and becoming a triumphalist gesture instead. This, in my view, is the defining characteristic of shame. Because the boundaries of shame are nothing if not constantly shifting in their fluidity. If you go back thirty years—to before the sexual revolution—the realm of shame was still primarily associated with exposed shame, that is, the body. These areas of shame no longer exist if we follow our visually recorded World; instead, they've been replaced by armor made of nudity, muscle, silicone pads, or similar materials. Because public shamelessness is unmistakable, we might conclude that shame has vanished, as it often mainly exists in culturally critical contexts. Skama—etymologically, it refers to what is covered and veiled. Conversely, it can also be said that what is only accessible in a hidden and veiled form represents the realm of shame. Following this logic—where we must infer shame from what covers it—it's clear that an exposed, uncovered body cannot be interpreted as shameful. Personally, I would suggest here that the focus is on the gender of devices—and that doesn't relate to shame, but to other contexts. The connection between tailfins and female breasts, washboard abs and lamellae...

Shame – that's an old word, a term that invokes laws of morality and religion. Now, considering all the pudenda, but also the major issues of guilt and atonement involved here, I am inclined to choose a more contemporary term. Instead of shame, we could speak of an unconscious. This would mean that, instead of a Freudian engine – which, as is well known, is Oedipalized and overly sexualized — a dynamic, historical entity would need to be assumed. And, as I mentioned, that's where shame fits in — it is no longer a fixed, once-and-for-all defined area of shame but rather one that shifts and changes shape. Wherever you encounter something concealed, you encounter the realm of the unconscious. In this sense, it's questionable whether we are shameless or whether shame has been displaced. We may have unveiled the mystery of sexuality, but try—invoking the same freedom of expression—to uncover your neighbor's tax secrets! The body-covering garments may be visually appealing, but they do not conceal the symbolic bodies beneath them – so it’s only logical to conclude from this darkness that there's a deducible »money unconscious.« Assuming this, we wouldn't truly be shameless; instead, our sense of shame would have shifted to a different, symbolic terrain. This shift is reflected in the meaning of a little, enigmatic joke circulating about Donald Trump, the multimillionaire owner of Trump Tower. One day, he encounters a beautiful young woman in the elevator of his Trump Tower. Since they are completely alone and the elevator ascends to the aptly named heights of worldly finance, she offers herself to satisfy him, specifically with her mouth. That is truly an unselfish offer; what man wouldn’t seize such a gratuitous act? But what does Donald Trump ask? ›What's in it for me?‹

Now, let’s move on to the question of hearing, specifically whether and why the Ear could be a source of shame. When I started working with sounds and noises over seventeen years ago (in a field that isn’t quite radio plays or music but somewhere in between), I was captivated by this field’s openness. The longer I worked with it, the more it became clear that noise, this amorphous sound, is similar to those »unidentified theory objects« that the Bilwet Agency4 introduced into conversation years ago, known as UTOs. This extraterrestrial, unfamiliar strangeness is all the stranger because noise is the most ordinary, most taken-for-granted phenomenon—yet no one has really studied the language of sounds. Indeed: the language of musical form has its own science. But even speech – which was one of the highest forms of art in ancient times – has become strangely silent, not to mention the voice with all its dysfunctions. But, as I mentioned, things become completely unclear when you enter the realm of sounds and sound perception. What exactly is a sound? That might seem like a stupid question. However, it makes more sense when looked at from a different perspective: when do we stop calling something just sounds, and when do we consider it music or speech? It's this dual distinction, on the one hand from music and on the other from language—that defines noise. However, this is not a positive definition; rather, it’s a negative one. Noise encompasses everything that is neither language nor music. Can the music playing in the background even truly be considered music, or is it simply background noise, a soundscape we carelessly ignore? And can the voice of the person I am listening to, who sounds endlessly bored, be anything other than meaningless noise, barely distinguishable from the echo of the espresso machine? Conversely, if the speaker enchants me, doesn’t that voice resemble the highest music of the spheres? Given the fluidity of the acoustic event, it’s no longer possible to definitively say: this is music, this is language, this is noise. What I hear becomes music because I interpret it as music, and becomes noise because I perceive it as noise. Therefore, noise can be viewed as a mode of hearing, or more specifically: of overhearing [Überhörens].

In fact, all these demarcations prove to be artificial separations whose essential function is to ignore the entire field. But why not? I remember sitting in a studio long ago and asking an editor to make an edit. It was a recording of a Zulu text that I had recorded on the radio in South Africa. What the speaker said was incomprehensible to me; it sounded like a kind of boxing match, very exciting, and the speaker built up to dramatic heights in an endlessly slow glissando movement. Only at one point did this glissando sag a little, and I said: ›Here, cut that out.‹ But, said the editor, ›That's right in the middle of the word. You can't do that. It'll destroy the whole meaning!‹

That’s a really strange objection. Here we have this woman who deals with sound material day in and day out, with nothing but sound material – and she intervenes. But in whose name does she intervene? In the name of the meaning of a language she doesn't speak – Zulu. This is a curious case, a belief in the word itself, where you don’t understand the word at all. You could ask whether meaning is contained in the word alone or whether it’s also expressed in the movement of speech in this intensifying, gradually ascending glissando. However, what intrigued me about the vehemence of her objection was the absolute unquestioning attitude, the matter-of-fact tone of this sentence: ›That can't be that!‹. So, I interpreted the objection as a moral gesture. Taken literally, it could be understood as: ›Don't destroy the integrity of this speech!‹ because, in the end, that essentially means destroying this person. Incidentally, it's not that I wanted to criticize this moral impulse. It's just that this moral impulse has little to do with the radio editor's practice, which essentially consists of piecing together snippets of interviews and otherwise eliminating every uh, every ooh, every tongue-clicking and lip-smacking. This is acoustic dirt, impure, and goes straight into the trash. In this sense, editing is not just collage; it’s sound hygiene—and the effort needed for these hygienic tasks is significant. This leads to the question: ›Why all this effort? Is it necessary, or is it just a kind of acoustic obsessional compulsion?‹—because we don't all speak as the printed word, but haltingly, hesitantly, with these uh-and-oh interjections. In short: what's being edited out day-in and day-out is nothing other than the human factor. However, returning to our Zulu speaker story, considering daily practice, the editor's objection seems even stranger. On one hand, it's acceptable to disinfect speakers acoustically; on the other, it's claimed that the cut—which isn’t hygienic but phonetically sound-based—is an unacceptable objection because it destroys meaning. What sense is at stake here? Undoubtedly, it is not the meaning of hearing, or how we perceive language and sound, but rather an abstract, quasi-non-physical meaning: what I would call the spoken-as-printed, as in a book. The dominance of this higher sense—behind which, if you go back to Philosophy – you can quickly find the logos, the metaphysics of letters—makes you deaf to the concrete sound event. Because of this boundary between linguistic meaning and acoustic nonsense, speech is cut off from its unique gestures. In this sense, it might be possible to speak of acousthenia similarly to dyslexia – except that this clinical condition is not considered as such, but seems to be part of a good tone.

This experience is not an isolated case — throughout my work, I've observed that those in this field spend a significant amount of their energy ignoring the acoustic material's idiosyncrasies. This raises an important question: What makes closing one's ears so dangerous? Where does this perceptual blockade originate? And why does it primarily affect that vast underground world of unprintable speech or the realm of non-instrumental pure sound? Undoubtedly, this represents a dividing line between pure and impure, and it is repeatedly drawn with a knife. The pattern of the cut is neither rational nor reflective; instead, it follows a reliable, unconscious logic: noise is what gets cut away. In doing so, the complexity and diversity of sound are sacrificed to SENSE — which must be understood in CAPITAL LETTERS.

In a seminar on the Semiotics of Sound I taught at the Free University5, I dedicated one session to having each student share two things: first, a childhood sound they could clearly remember, and second, a present-day sound that was vivid in their mind's Ear. What emerged from it was quite strange. Exemplar was a young woman who described lying in a doghouse in the forest at night and perceiving a sound she couldn't identify, as if it were coming from another being, and how suddenly everything felt threatening. Then, the same woman shared a childhood sound: a very close smacking or lip noise she heard when she woke up. And she knew: that was her mother waking her up by grimacing and making grotesque faces, hence the noise of the lips. When she opened her eyes now, she would see her mother's face making grimaces in front of her. And while she's telling this story, I look around and see the faces of the listeners, who are asking themselves: ›What kind of a weird mother? And what on God's green earth is that daughter doing in a doghouse in the forest at night?‹ But these looks were not malicious, as when someone makes a Freudian slip of the tongue, but somewhat sympathetic. This difference is quite unusual, as it sharply contrasts with how we perceive images. In the simplest terms, we could say: we own images but don't own sounds. There are no acoustic property regulations—instead, there is pure, innocent communism.

Or, if you want to grasp the difference historically, which I would prefer: the hearing, obedient [hörig] human being is not the same as what we call the subject. However, that's not surprising since the constitution of the modern subject relies on a visual technique: we create a frame, place ourselves within it, and then fix, determine, and objectify what becomes visible from inside the frame through the construction of a Central Perspective. When I am the subject and objects are positioned opposite me, it's only because, in pursuing this modern project, I am in the picture. But try transferring this arrangement to acoustic perception. How can I identify an acoustic object? Where would the frame be? Naturally, the joke is that the acoustic object never appears as a single entity. Even if there were only one sound source, the space in which this sound appears always resonates: it alters the sound and acts as a sounding board. Sounds are always mixed, sound spaces—not individual objects. In this sense, talking of pure sound— from which musical imagination has led us to associate with the Music of the Spheres—reveals deep contradictions. For pure—if you will, mathematically pure—sound is the sine tone, which we experience as completely inaudible in real life.

And there's another impossibility: namely, visual distance. You can't position yourself directly opposite the object without being seen, as if behind a glass partition, but hearingly you're always pushed into this space by what you hear. Just as noise is inseparable from the surrounding space, you are also part of this space. This being-in [In-Sein] is the foundation of our perception of sound. But that means we have a different relationship to the World when we listen. As already mentioned, this must be understood from the perspective of sensory technology.

Take musical notation as an excellent exemplar of how sound has been conceptualized over the centuries, which didn't just emerge coincidentally at the same time as the central perspective. If you look at a page of musical notation, you notice it ignores everything that makes up the world of sound. While a hand clap sounds quite different depending on whether it occurs in a small, stuffy room or a bathroom—here, there's nothing more than an abstract, spaceless, tonally undefined impulse. Classical notation functions how Galileo formulated his desire for a perfect gravitational system: »Think away the air!« But in reality, the air acts as the medium for the reflexion of sound, its refraction by various materials. It must be said: musical notation functions like MEANING in all caps or, to put it figuratively: as an abstract program, as instructions for music boxes to be played in weightlessness and perfect silence. No matter how absurd this idea may seem, it nevertheless conjures up the image of an ideal subject who, unburdened by space's conditions, has mastered their instrument.

Viewed this way, the resistance that manifests as amorphous noise that mixes and blends uncontrollably with other copulas, like a dissolute, unwashed, and unkempt being, is understandable. Here, the observer's mind, as the modern subject, clashes with a foreign, almost hostile principle. The language of sounds, if they haven't been elevated into abstraction and thus rendered obscure, has little in common with the Logic of Representation. When I mention the Logic of Representation here, I refer to the Worldview Machine of Central Perspective, which has shaped how we perceive Images, Philosophy, and Political Machines. It's a complex concept deeply embedded in our behavior. What do you ask when you see a picture? ›What is it, where is it, who is it?‹ Or—if there’s nothing figurative to be seen on it – ›How much was it? And who painted it?‹ This perspective, if I can borrow a linguistic term, is deictic. It defines space and time, identifies, classifies, and evaluates. While this may seem natural to us, it’s actually a historical technique. Since Jan van Eyck painted the Arnolfini portrait in 1432, it has borne the artist's signature and date. And since then, the exchange of Images for Numbers has continued.

Please forgive my brief dives into cultural history. I've covered this in detail elsewhere, and to keep the thread intact, I won't go into it further. My exploration into cultural history was primarily driven by how much we're still influenced, even obsessed, by ideas rooted in the visual sphere. Because I've learned to categorize this, I better understand why the panacoustic space gets such neglect. One of the most striking oddities for me has always been the way words are treated— or rather, subjugated. Indeed, there's no area of human life where resistance to being defined is stronger than in the world of words. Of course, you're free to impose a definition, but, as Nietzsche famously said, ›Only death is definitive.‹ To want to define something means to turn a deaf ear to what language itself tries to communicate. Every word I receive is laden with semantic contraband – whether I like it or not, its pronunciation carries a significance I didn’t create myself.

What I mentioned at the start of my lecture about the architecture of information also applies specifically to words. Just as the screen only shows us the graphical surface, with words we only perceive the latest, current layer of meaning. The supposedly secure idea of the subject, which we have narcissistically supercharged, is actually a very fluid, changeable quantity: in French, the sujet still means what is, what is the object [Objekt]—the item [Gegenstand]. And if you look far enough back, you'll see in this particular subject the sub-iectus, meaning the subjected—whereby the autonomous subject has been transformed back into its opposite. Seen this way, etymology is the unconscious of language, and the traumas and neuroses of the time have been written into words. This isn't to say that the displaced word-meanings inevitably rise from the graves as semantic zombies and haunt us with their never-ending past. Some things are dead, and maybe that's a good thing. On the other hand, it's helpful to remember that what we call »definitional power« [Definitionsmacht] is nothing more than the explicit denial that we've received language – and did not create it ourselves. And so, lurking behind this definitional power is the shame of having received the mother tongue, the shame of having been born. If we admit this constitutional shame, the world of words opens up – we will discover with surprise that the descent into the semantic abyss isn't an entry into a yawning abyss but brings to light layers of meaning corresponding to our current questions.

The psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan didn't interpret regression as simply stepping back, but rather as a »return to unfinished business.‹ That means that when we regress, we don’t become infantile but instead return to the place remaining unresolved, a question still open. There’s something gaping—right now, in the present. It's similar to my plastic surgeon friend, whose girlfriends all look like clones, identical to each other, exemplifying the classic repeat offender. But what motivates this repetition? This is where the importance of Lacanian regression comes into play: a return to unfinished business. Exploring the etymology of a word also means: retracing the chain of the same, considering the differences and possible variations within a field of meaning. It's no longer about a single meaning anymore but about how the word, with its various connotations and masks, appears within the language field.

As an exemplum: Classical linguistics, since Saussure, has taught us that signs are considered arbitrary. At the beginning of the century, the significant idea of the arbitrary sign reared its head. If you look into Philosophy that speaks of autological systems, language games, or similar concepts—the so-called »Analytic Philosophy«—you will find that all its major achievements rely on the idea of the arbitrary sign. That is the »currency« it uses for its calculations. Ask an adept of this school what »arbitrariness« means, and he will either refer to the arbitrariness of the sign or explain derivatives of that same idea, using terms like »self-referentiality,« »autology,« or similar; in short: he will answer a tautology with another tautology. But that word, like almost every other, has a long history. If you look it up in the dictionary, you'll find the same meaning under »arbitratus«: »arbitrary,« »at will,« »random.« But if you look up »arbiter,« the picture becomes much more complex: We have the attendant, the confidant, the referee, and then—you can almost see someone claiming authority here—the ruler and director, and finally: the Executioner. This immediately raises the question: What in God's name is the connecting element, and how did it come about that only the meaning of chance is all that's survived all this? Now, I hope this irritation will disappear immediately when I tell you the following story. It’s about the arbitrary sign par excellence, that piece of paper with a number written on it. As is well known, paper money is a Chinese invention, so the hero of this story is the Chinese emperor. Let's suppose the emperor has cast a covetous eye at his subject`s house and offers him an arbitrary token for it. Let's assume that the note is so large that the subject will never be able to exchange it. He will probably refuse to accept this symbolic sign. But what then happens? The sovereign's answer is brief and harsh: he will execute the person involved for insurrection and lèse-majesté. To avoid any misunderstanding: this isn't a Chinese peculiarity; in the early modern period, not accepting a sovereign also led to imprisonment, banishment, or similar punishment. And why, I ask you, does only the State have the right to issue money and strictly prohibit me from issuing my own currency, the Burckhardt, under penalty of severe punishment? No, if you understand the meaning of the word, you grasp the whole story, not just the current issue. At this point, we could sing the praises of listening, because it is through listening that we can delve back into language and perceive the contraband of thought, its overtones, vibrations, and connotations. This is, if you will, the gift of language. It consists precisely in this: that words, even if their respective era has given them the appropriate costume of meaning, always also carry something of their prehistory, their field of meaning. And because we can return to this prehistory, we are not condemned to revisit unfinished business without knowing it, to repeat the old in the new. To grant something means that I can also stop.

Seen in this light, the Ear wouldn't just be a place of shame but also a place of advanced reflexion. These are closely connected – you don't become immersed in reflexion for the love of the beautiful, the true, and the good, but instead, it's embarrassment that compels you to reflect, an attempt to prepare yourself for the future. Günter Anders once gave a fairly precise description of what characterizes the feeling of shame. He described shame as the result of an aporia, a paradoxical dual sensation. On one hand, there is someone who knows, I DID IT – and on the other, there's the certainty: THAT IS NOT ME! From this starting point, Anders analyzed our relationship to technology – the fact that we build Machines so much more perfect than what unadorned man is capable of – and described this relationship as »Promethean shame,« a curious mixture of megalomania and embarrassment. If, as I assume, you are a television viewer (with or without a guilty conscience, it doesn't matter), you will be familiar with the advertising campaign launched by AOL featuring computer novice Boris Becker. It plays precisely on this theme of »Promethean shame.« ›IT'S ME. IT'S NOT ME.‹

A few years ago, when I was conducting a seminar with actors, I had an astonishing experience: the young actors reacted much more strongly to their acoustic performance than to a video recording. While they usually looked quite self-satisfied when shown the images, their reaction to the disembodied voice was unanimous: ›THAT'S NOT ME!‹ And then: ›Come on, let me try again!‹ – The question of where this almost reflexive resistance (which is just as impulsive as the editor's resistance) originates has greatly occupied me. Is it really just the sound of one's own voice being perceived as foreign and out of place?

To find out, I did another exercise, the sole purpose of which was to eliminate any control over the text. So, I asked the acting students to transcribe a text as they pronounced the words while coordinating it with the movement of their hand, just like children doing their homework. The amazing thing about the result was that it was much easier to follow this version of the text, and the reaction of ›That's not me!‹ didn't occur. Constitutionally, the task had a moment of imperfection, a handicap built into it, thus preventing the result from being rejected as inappropriate. From this, we can only conclude that the moment of embarrassment or shame comes from confronting the psychological image the voice evokes—and that this Imago doesn't want to align with our outward Optical appearance. What's inscribed in our voice is more complex and contradictory than what our outward appearance reveals. The voice can't be masked. It exposes—and is exposing. Suddenly, there's a lump in the voice, a hoarseness, a clearing of the throat, and it takes your breath away. What comes to light here is the shame of the Imago—that which lies beneath our surface image.

The path from the Eye to the Ear describes the path to inwardness. Goethe already grasped this leap in a small synesthetic turn, or rather, he made it clear by crossing the visual into the acoustic: ›One feels the intention – and one is out of tune.‹ Behind the façade, another space opens up. It's evident that the idea of detuning isn't about sound but about psychoacoustics—and this aligns with Novalis' early 19th-century motto: »Inward goes the mysterious way.« When you analyze the language of inwardness, you'll be struck by its rich vocabulary: it references constant discord and harmony, subtle vibrations, and more. Inwardness need not be read ideologically or aesthetically; it can also reflect a profound and material cultural shift. The era of frozen images ended in the 19th century, giving way to the age of time. Metaphysics shifted into Metabiology: Time flows, and it does so faster than the eye can perceive. When high-speed photography captured the flight of a bullet at the end of the 19th century, it not only documented technology's triumph but more importantly, revealed that we live in a World where the invisible is real.

Perhaps it is now clearer where my interest in acoustics originates. It relates to the invisible world, but it also concerns the structures within that world. The strange thing is that pre-modern thoughts intersect with post-modern life experiences – which, if you listen to music, can be identified as a contemporary trend: Gregorian chants, music for spaces, techno, immersive environments, and the like. Here, we could discuss a Renaissance of the Middle Ages or the Gothic period, even if this blurs stylistic categories. In this context, we can say that the voice is the anima, the seat and source of the soul.

And yet, while it’s natural to draw inspiration from the older layers of a word's meaning, there's something deeply problematic here. All too quickly, you find yourself in a bubble of harmony and bliss, where you're assured of the approval of like-minded individuals—but at the cost of intellectual insight into the structures of our present. At precisely this point, however, my engagement with the sounds has proven immensely beneficial: not just receptively but also in processing them. Here, it seems to me that sounds have a conceptual added value, revealing the outlines of the continent we are currently heading toward, perhaps flying blind. If you will: in the medial treatment of the anima, we should no longer see it as pure unheard-ofness [Unerhörte], but as a being that is always historical—its actual state of mind becomes visible. Just as we edit our symbols, we also edit ourselves. With that in mind, I want to turn to radio, or more precisely, to those voices that radiate into space, leaving their bodies behind. These voices are, if you will, the prototypes of the Identity Machines we encounter in the Internet age.

In some respects, the genealogy of radio is profoundly important. As many know, radio played a vital role in seafaring; it acted as a navigation system that, in the early 20th century, was as crucial and advanced as today's Global Positioning System. In April 1912, a young man named David Sarnoff was sitting at the Wireless Telegraph Company in New York when he intercepted messages from somewhere in Newfoundland: the SOS signal from the sinking Titanic. Aware of the impending disaster, he organized a 72-hour conference call between various radio stations. In this sense, the sinking of the Titanic was the first live broadcast. Soon after, the young Sarnoff founded RCA, the first radio station. In other words, on the day the Titanic sank beneath the Atlantic, the imaginary, virtual space of radio waves blossomed. This interpretation might seem too simplistic, perhaps even audacious. Therefore, I’d like to add a few more details to this strange story, as told by another witness. He was also a radio operator, but he served as a radio officer on the Titanic, and what he reported was no longer live; it was that part of the story about sheer survival. Harold Bride had left his radio and decided to disembark. However, not all crew members were so concentrated on survival. As an exemplar, there was a string sextet of musicians who stood there and played and played and played.

»From aft came the tunes of the band. It was a rag-time tune, I don’t know what. Then there was “Autumn”…The big wave carried the boat off. I had hold of an oarlock, and I went off with it…The ship was gradually turning on her nose—just like a duck does that goes down for a dive. I had only one thing on my mind—to get away from the suction. The band was still playing. I guess all the band went down. They were playing “Autumn” then…The way the band kept playing was a noble thing. I heard it while still we were working wireless, when there was a ragtime tune for us, and the last I saw of the band, when I was floating out in the sea with my lifebelt on, it was still on deck playing “Autumn.” How they ever did I cannot imagine.«

When Harold Bride, the eyewitness, returned to New York, he was greeted by a deeply moved Guglielmo Marconi, who shook his hand. Why the emotion? Marconi, though a physicist—and primarily interested in the efficiency of his apparatus—was anything but a mere scientist; in fact, you could say he was something of a Pata- or Metaphysician. Until the end of his life, he believed that sound waves never truly die but only become quieter and quieter. That’s not true: when a sound is produced, the sound waves travel through the air, reproducing themselves across countries and continents—and we know that within 24 hours, the entire atmosphere changes because of that sound. If there were a device that could read this, the air would be a library of everything ever spoken—and as if to show that this goes beyond just physics, Marconi suggests it might then be possible to hear what Jesus Christ said—meaning the air itself, the ether, would represent a Sacred Text. This idea isn’t unique to Marconi; the computer pioneer Charles Babbage also expressed it in nearly the same way in his Ninth Bridgewater Treatise. Here, we encounter a concept of anima, an idea of immortality related to the material from which radio waves are fed. If I mentioned panacustics earlier, this is the theory behind it. What’s important here is that in order to read something requires a very different approach than identifying a visual object—because you need to understand the entire system to grasp a detail. The connection between body and space is constitutional and systemic.

So, you shouldn't be discouraged by the almost religious aspect of this idea. What is revealed in this fusion of technology and mysticism is actually a new ratio — and in this sense, techno-mysticism acts as a kind of transitional symptom – something reminiscent of the Middle Ages when the Wheelwork Automaton [Räderwerkautomat] was celebrated as a divine gift. Seen in this light, it is more accurate not to search for the timeless, metaphysical soul here but rather to focus on the specific anima existing in the conflict zone between the desire for eternity and technical reason. Some might call it an Identity Machine, albeit a bit pretentious. Of course, the key question about its constitution is which principles dominate. This leads me—at last—to the issue that has deeply occupied my thoughts during my work with acoustic material.

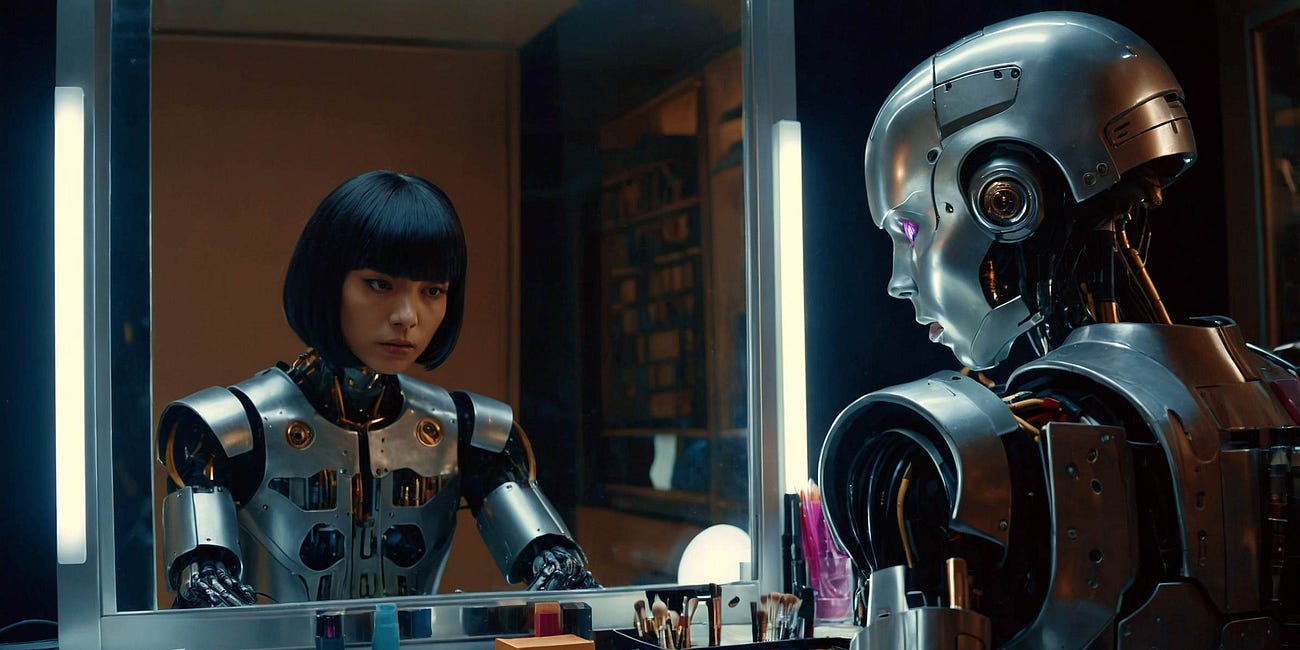

In a certain sense—and this is probably why I have an immediate emotional response—this is all predetermined in the story of the sinking of the Titanic. This image struck me as an afterthought that explains everything I find appealing: namely, distorting the acoustic material, slowly transforming it in slow motion, giving it rhythm, and allowing it to sink into the background noise. Then, throughout this process, you ask yourself – ›If you don't see yourself as a particularly destructive type - what drives you to do this?‹ But above all: ›Where does the sense of beauty conveyed by such a sound event come from?‹ The answer, I would say today, is that all these operations—symbolically—reveal the transformations we’re experiencing today. As you work with the symbols, you’re also being transformed yourself. More generally, what’s clearly seen in all these operations is the formation of the modern subject. This subject no longer shares any traits with the image that the early Renaissance gave us—a cropped arch: a half-length portrait against a deep landscape. In other words: the fading forms of myself and the scattered existences no longer fit together into the unity suggested by the image. There is, so to speak, an underlying maritime layer; a radiance that extends beyond the body's boundaries – and ultimately, there's the community of ear witnesses who, aware of the sinking, come together as a community—as Peter Sloterdijkonce put it very nicely: the nation as a vibrator of worry. Given all these realities, claiming that I am a singular individual doesn’t make much sense. In fact, I fragmentally divide myself into parts, creating partial existences. Some of these parts are virtual, like the voice on my answering machine, which will keep taking messages long after I’m dead, or they may, as agents and avatars, act as revenants of my free will, haunting the internet. You might be tempted to see all these electromagnetic shadowy existences as simulacra-inauthentic, unreal attachments. However, these virtual shadow beings have long influenced my true self to such an extent that I have to ask: what would he be without them?

The contemporary apotheosis of the communication concept can also be interpreted in its entirety. To the extent that I'm encouraged to share, I divide myself, developing differentiated parts of myself – and, nolens volens, becoming a kind of dividual, a free-floating mass being. Here, it makes more sense to interpret parts of this identity aggregate not as a corpuscle cut off from the world but as a wave, from the perspective of how this being appears in the surrounding space. The dissolution of the body center—our primary site of personality formation—might explain the appeal of the current body cult. Essentially, the closure and perfectionating of the body aren't signs of Narcissus' apotheosis but of his growing dissociation. It’s no coincidence that people pump themselves up with silicone and anabolic steroids. But perhaps we don't need to dramatize this at all. The demise of the subject—as a world-less, individual, or, to put it another way, an indivisible unity—doesn't mean that we will no longer say »I,« but it says: that the fantasy of the imago, that our physical outfits no longer apply, that the grammar of representation has reached its conclusion. It’s precisely at this point that the examination of sound becomes fascinating as it reveals that we are inherently situated in different spaces, making the clinical distinction between subject and object irrelevant here. We disperse, lose ourselves in these spaces, and descend into submarine zones. Many terms describe this concept, and it’s more or less explicitly present in all modern theories. Take Luhmann's system theory, which consistently focuses on the relationship between the system and its environment.You can see that the dissolution of the individual is already embedded in this edifice of thought, where the concept of the subject has shifted to the social institution, encompassing the discourse on power, recognition, money, and love. Naturally, because of this, it is wrong to proclaim the death of the subject—we will still say »I« in the future.

This is precisely where modern sound processing techniques become fascinating. Unlike film, which fundamentally relies on editing—based on the logic of presence and absence—the main question in the field of sound is how a body appears in space. Focusing on a worldless body without sound, however, isn't very useful—this would mean viewing the sine tone as the perfect sound. But sound is always a composite: necessarily composed of its own rules and external factors, including the sound source and acoustics. Technically speaking, it’s about the blend: how does this body relate to its surrounding space? From this view, it's not surprising that much of sound editing is less about editing and more about mixing; it's about creating mixes and remixes. If I elevate this to a philosophical level, the key figure in the formation of the modern subject is what I would provisionally call the hybrid. You deconstruct yourself and constantly rebuild yourself anew. Where the ideal image was once that of uniformity, now a picture of a flexible, Protean existence is emerging.

Well, at this point, there's one element I'd like to briefly mention so I don’t overstay my welcome. The sea we're sinking in is simply software. To drown in it means to face the nature of digital logic. Digitalised, I become a sample of myself. The basic formula of the computer is x = xn. That may sound meaningless, but when applied to the zero or one, that is, to the foundations of the system—it makes sense. When I see my digitalised shadow, I am not looking at a double but at a gene pool, a multiplex, a multitude. Such a shadow is necessarily susceptible to the threat of proliferation—and in this sense, the term original is outdated or, more precisely: superfluous. The reference to genetics here is neither coincidental nor metaphorical—as the procedures of sound processing are, symbolically speaking, genetic operations par excellence. You take an original string and then apply an algorithm to it. The resulting derivative is a hybrid made up of the original sound and its modified offspring. Unlike a static entity—say, a computer-edited photo—these processes are dynamic, reflecting the nature of sound. If I visualized this as an image, you'd see a pulsating form that expands and contracts, shifts its shape and structure, and can split apart and swarm—basically, a constantly changing, shape-shifting being. These descriptions are unnecessary here, as I’m sure you’re already familiar with them as part of our daily experience. A good example in this context is Techno music, which reflects the metamorphic body through the continuous blending of sound and ambient space and the shift from one to the other. That's what makes it ecstatic. Ek-stasis: literally, stepping out of oneself. In this process of stepping outside oneself, the body is experienced as a permeable entity that merges with the outside, allowing you to see your own body as part of a collective where the group's rhythm pulsates—boom, boom, boom. This parade of vibrating, twitching bodies is a passionate expression of decay: what it means to feel yourself as a divided individual, moving within the flow of others. If you will: the heroic gesture of the musicians on the Titanic, sinking into the sea, is replayed constantly in techno. But to what purpose? Perhaps to celebrate the shift into virtuality, into the realm of appearance and incorporeality.

Perhaps that’s why, although I want to sing the praises of the Ear, I don’t want to be all ears. And perhaps now you understand why I have a protruding Ear – and yet I prefer not to have it fixed. Thank you for your attention.

Translation: Hopkins Stanley & Martin Burckhardt

Translating Hörigkeit into English is complex because it encompasses the ideas of both hearing and becoming bound to who or what is heard. Although it originally comes from the Medieval notion of a farmer’s dependency on his landowner, its meaning has evolved over time to describe the unconscious and conscious submission of one's will to another, sometimes implying sexual bondage; it can also be seen as a form of co-dependent personality disorder. Notice how Martin plays with the term’s complex polysemy as a wordplay in this lecture.

Burckhardt, M. – Vom Geist der Maschine: Eine Geschichte kultureller Umbrüche, Frankfurt/Main, 1999.

Given as part of the symposium: Gehör und Hörigkeit [Hearing and Servitude], Protestant Academy of Tutzing, March 26, 2000.

The working name of a collaboration between Geert Lovink and Arjen Mulder.

Related Content

The Price of Identity

The following essay is a translation of a piece Martin wrote for Lettre International, Europe’s leading cultural magazine, in the fall of 2019. It continues a line of thought that dominated his first book: the connection between images and numbers. While this may be evident on every coin, the dual emergence of Central Perspect…

The Invention of the Mouse

A mountain is in labor, then gives birth to a mouse. (Horace, Ars poetica). Which raises the question: What becomes of such a mouse when it grows up?