The Price of Identity

The Birth of Modern Subjectivity, read as a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde narrative

The following essay is a translation of a piece Martin wrote for Lettre International, Europe’s leading cultural magazine, in the fall of 2019. It continues a line of thought that dominated his first book: the connection between images and numbers. While this may be evident on every coin, the dual emergence of Central Perspective and the Political Philosophy of the Florentine Catasto remains largely unknown to this day – just as the discussion of representation drifts within a peculiar void. From this perspective, tracing it back to its concrete historical origin is nothing short of essential. Only in this way can the complex relationship between the self and society be understood.

— Hopkins Stanley

Martin Burckhardt

Image and Number:

On the Nexus of Subjective Constitution, Central Perspective, and the Social Projector

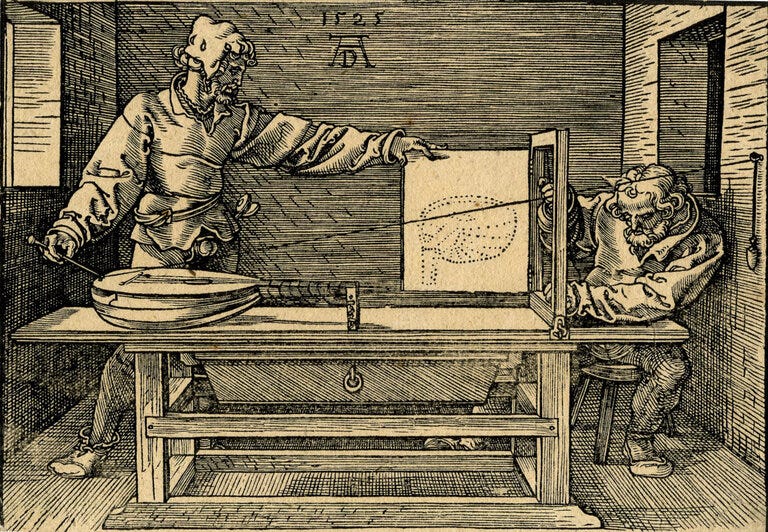

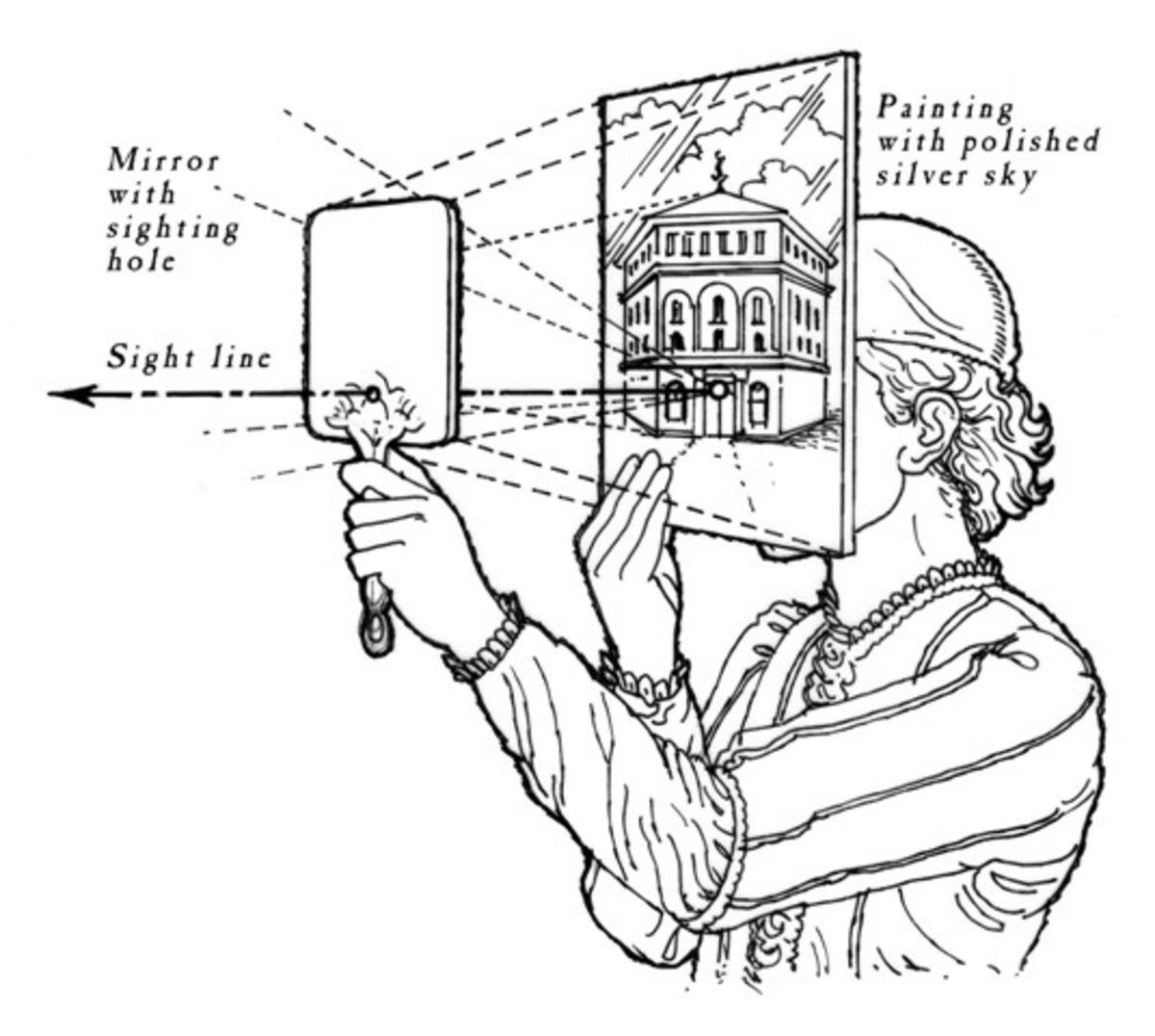

If we recall the history of the enlightened subject, it's usually told as a heroic self-conception: a series of rule-breaking wrestling the Self from the grip of ecclesiastical and secular authorities.1 What remains is the radiant self-portrait, an intensity that translates into the logic of the selfie. This story, in which the Renaissance appears as the dawn of the Enlightenment, has always been a hero's tale that could only claim validity if its concrete origins remained in the dark. If we look closer, its subject appears not as a solitary figure but as an I-in-Society [Ich in Gesellschaft]. Insofar as this subject wears a social costume, we know then we're dealing with a complex set of rules in which the ratio between selfhood and social order is articulated in a highly entangled manner. Conceptually, the distinction between subject and object remains strangely fluid well into the 18th century, which is exemplified by the German word Subjekt and the English word subject. Here, a conceptual clarification inevitably refers to the Logic of Central Perspective: the connection between the observer and the observed, which assigns both subject and object their place in the setting of a central perspective. Suppose the projector reveals the world in relation to the painter's position, as an objective state of affairs; in that case, this placement positions the painter in the position of the world-designing or analyzing subject, depending on the case. Insofar as the central perspective of projection is reproduced in the speech act of subject and object. It’s always a matter of selecting a point of view, setting the framework, and objectifying the opposite – a context of communication that assumes the Central Perspective’s project as a system of rules, effectively serving as a verifier of truth.2

Insofar as the idea of the autonomous subject disregards this connection, it goes hand in hand with the repression of the conditio sine qua non. This act of repression is all the more remarkable given that, ultimately, we’re confronted with a centralized perspective that’s ultimately a mechanical order, a process that can also be performed by an image-processing device: the camera obscura. The prevalence of terms such as point of view, perspective, and framing conditions dominating today's political vocabulary indicates just how deeply this ratio has become ingrained in our thinking—and how much our worldviews continue as a function of the Central-Perspective Projector. But if this projector represents a blind spot for those born later, the question arises: can we simply stop at the abstraction limit of Central Perspective’s logic? Shouldn't we broaden the inquiry to encompass the structure of representation constructed under the aegis of this projector?

Tribute Money

Although many commentators have criticized the Concept of Representation as leading into conceptual shallows, even an intellectual quagmire,3 they overlook that rappresentare in Central Perspective denotes an exact, intersubjective form of worldview. The famous mirror experiment that Filippo Brunelleschi conducted in 1413 in the Duomo of Florence’s Baptistry and which grasped the laws of Central Perspective marks a clear caesura. Here, the rays of vision aren’t seen as products of an individual act of perception but as a physical law that can be reproduced by an optical machine—a camera obscura.

In contrast, the medieval use of the term is infused with complex theological considerations. During the Middle Ages, the word repraesentatio was used to denote the real presence of an absent person. In this specific sense, the Eucharist’s Oblate represents Christ. Moreover, repraesentatio itself referred to a kind of divine database, acting as the directory of saved souls in Heaven’s Book of Life. Considering this history, the centralization of the gaze—which can be interpreted as an anticipation of the Cartesian system of coordinates—is paired with a notable simplification of the thought process behind representation. One of the earliest images in art history to employ this technique is Masaccio's fresco in the Brancacci Chapel in Florence, known as The Tribute Money [Zinsgroschen],« 1427.

This reference is remarkable because the history of taxation can reflect on a precedent corresponding to the rethinking of the idea of representation. In this context, the Treasury, that is, the secular authority for tax collection, is envisioned according to the model of Christ. Consequently, a document from that time can succinctly assert: »Quod non capit Christus, capit fiscus,« meaning what Christ doesn't snatch is snatched by the taxman.4 In this sense, secularization signifies a shift of power such that the secular center of authority absorbs the legitimacy of the supermundane’s authority. Seen in this light, it isn’t surprising that Masaccio's Tribute Money remains within the realm of biblical thought and specifically questioning the relationship between the heavenly and earthly orders. The Bible passages alluded to by Tribute Money are Matthew 17:24-27 and Matthew 22:15-22, where Jesus responds to the Pharisees' trick questioning whether the Jews must pay tribute to the Roman emperor under the doctrine of two kingdoms: »Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar's and to God what is God's.« In the scene from Matthew 17:24-27, referenced in the motif of the painting commissioned by Felice Brancacci, Peter is confronted by a tax collector who asks whether his master will pay the customary tax of two drachmas. This scene raises the issue of the two kingdoms, as Jesus asks Peter:

»What do you think, Simon, from whom do the kings of this world collect duties and taxes? From their own sons or from other people? / When Peter answered, From the others, Jesus said to him, So the sons are free. / But so that we do not offend them, go to the lake, cast your line and take the first fish you bring up, open its mouth and you will find a four-drachma piece. Give it to them as a tax for me and for you.«

Strictly speaking, this answer is even more convoluted than the brusque two-kingdom theory because, parallel to this-world/afterlife distinction, there's also an inner-worldly divorce: between self and other, an endogenous and exogenous system of order. Basically, however, the doctrine of the two realms is reinforced, as Jesus insists that the Children of God, in principle, are free. However, due to their worldly existence, they belong to a worldly order that must be fulfilled to ›cause no offense.‹ This petitum, in turn, prompts Jesus to perform the miracle of creatio ex nihilo, the generation of drachmas—which today, as fiat money, is regarded as the most prestigious privilege of the Central Bank. This is the precise sequence of events depicted in Masaccio's Tribute Money. As ordered, Peter goes to the lake, takes a four-drachma piece from the mouth of the first fish he finds, and hands it over to the tax collector – which involves the somewhat bizarre but not uncommon logic in early Renaissance art that a character appears several times in the nunc stans of a painting – as if it were a comic-strip. Now, the question we’ve already encountered in the context of subject, object, and Central Perspective arises: What is the connection between the unleashing of self-image and issue of the tax or money?

Two realms

The answer is simple: the Masaccio fresco dates from the year when a catasto, that is, a modern income tax, was levied for the first time in Florence. There's no doubt that the transubstantiation from Christ to the Treasury, that is, from theology to the early Modern State, is palpable in the air. Indeed, a closer look reveals that the idea of Central Perspective originates not so much from the need for a universally binding production of the worldview as from the question of money. Let's examine the biblical passage in which the Pharisees ask Jesus whether it's right to pay taxes to Caesar.

And he answers: »You hypocrites, why are you tempting me? / Show me the tax coin! / And they handed him a silver penny. And he said to them: Whose image and inscription is this? / They said to him, Caesar's / Then he said to them, Give to Caesar what is Caesar's, and to God what is God's!« (Matthew, 22, 17-21)

The question of the image and inscription stamped on the coin highlights the great monetary issue of the 14th century. After Gothic Europe established notable gold coinage in the 13th century, with the introduction of the florin in 1252, followed by the French écu in 1262 and the Venetian ducat in 1284, the medieval world became increasingly monetized, driven by the Wheelwork Automaton [Räderwerkautomat], the growing division of labor, and the logic of interest. Inevitably, currency quality became a social desideratum, and it wasn't a good sign when you had to verify money by biting into it. Nevertheless, counterfeiting was rife. The princes, responsible for the coinage business, had soon discovered for themselves the possibilities of miraculously multiplying money. So they acquired other currencies, melted them down, added inexpensive base metals, and re-issued these coins with their own stamp. This abuse of the right to mint coins reached such heights under the French King Philippe le Bel (whose counterfeiting was so prolific that Dante unceremoniously consigned him to hell,) presented society with a phenomenon of inflation that was hard to comprehend. Worse still, this miraculous deterioration of money erupted into social unrest. Although the scholastic discourse addressed the devaluation of values, it missed the point simply because the question of a just price moralized the issue while ignoring the structural questions of the monetary system. It wasn't until the mid-14th century that Nicole Oresme raised the question of who actually owns the money. The traditional answer was that because each coin bore the image and name of the king who issued it, it remained his property, while its bearer only possessed the right to use it, similar to licensed software. This idea, where money serves merely as a measure of value—like a thermometer—was challenged in Oresme's 1357 treatise on the devaluation of money.5 He instead argues that currency is akin to an omnibus, a resource belonging to everyone: a common good that must be preserved in its goodness and intrinsic value. From this premise, he develops a theory that can be perceived as a form of a politically centralized perspective. Even though he concedes the king's right to mint money, this is only assumed under the condition that he acts as a community representative—thus, he is controlled by it. Pressed into such a framework and elevated to the position of the community's most senior employee, the prince should henceforth fulfill his duty and provide society with a reliable means of payment. Should a neighboring prince decide to counterfeit the coin, this would be considered interference in internal affairs and thus a cause for war. Not only does this theory anticipate the logic of the Central Bank, the Nation-State, and the Parliamentary Budget Veto, but it also clarifies the extent to which money shapes medieval society. Just as the visual rays penetrate visible space, money penetrates the realm of goods. This proto-Capitalist perspective fundamentally alters the status of the community. While the Stoics viewed the State as the embodiment of the tribal family, a mega-body expressing a form of blood ties, the idea of a Polity conceived as a purely symbolic, abstract order emerges here for the first time—making it no longer comprehensible from the standpoint of the zoon politikon. The significance of the Central Perspective lies in its spatial creation that marks an abstracted Symbolic Order6. Here, we're dealing with a highly complicated structure where it becomes clear from how this space – like every coin – has two sides, Image and Number, and the need to bring these two sides into equilibrium. However, it's no longer about this world and the next, the heavenly Jerusalem and the earthly kingdom, but rather about the relationship between the individual and society, the question of what duties the atomized self owes to the collective subject and which freedoms it can claim for itself.

Politics

That the Florentine patrician Felice Brancacci chose Tribute Money as the central motif for a painting in his chapel speaks to an eminently political mindset.7Monetization not only brought the issue of taxation into public consciousness but was also an existential concern for the Italian city-states as they were engaged in small-scale guerrilla warfare, resulting in a continuous shortage of funds from the employment of various mercenary troops. Following Venice's exemplar, Florence issued government bonds as early as the mid-14th century—the so-called monte. However, these bonds accumulated, plunging the republic into insolvency and leading to a banking and confidence crisis. Since the city had been at war with the Duke of Milan since 1421, closing its financing gap was of the utmost urgency. To enhance the city's economic prospects, Brancacci, a prosperous silk merchant and chairman of the Florentine merchant guild, was sent as an envoy to Cairo in 1422/1423 to acquire the same rights from Sultan Al-Ashraf Abu Al-Nasr Barbay as the cities of Genoa and Venice, that is recognition of the Florentine currency and the freedom to trade in the Mameluke-controlled territories: Egypt and Syria. Brancacci had proved himself worthy of this task: The florin was accepted as a means of payment and it was agreed to establish a permanent representation there. Nevertheless, this didn't resolve the city's issues. So they contemplated a previously unheard-of measure: per capita tax. While the sovereign bonds in the 14th century were already an astonishing action, a universal tax levied on each citizen was unprecedented. Until then, citizens had paid direct taxes on their estates, known as the estimo – along with a series of indirect taxes called gabelle collected from merchants on their goods at the city gates. Imposing a tax on every working Florentine citizen sparked a significant uproar. The oligarchy was particularly reluctant to bear the catasto tax’s brunt, pointing out that the lower classes would face much lighter taxation and that such a drastic measure would lead to an exodus of capital. Minerbetti, a silk merchant like Brancacci, argued as follows: ›Our city is governed by business, and if there is a catasto, those who have a lot of money will leave the country which is why it is concealed and not taxed. And so the whole business suffers.‹8 This line of argument could have just as easily been formulated by a modern-day industrial representative, making it clear that the State is conceived as a functional context; in other words: its drive [Triebwerk] isn't based on patriotism but on commerce. Our well-being, as Minerbetti summarizes in his position, depends on filthy lucre – salus nostra in ordine pecunie consistit9. Although he only expresses a platitude borrowed from the Roman historian Sallust, this statement holds special significance in the context of Central Perspective. Given the nature of this radical measure, there's only one possible legitimization: the promise that tax legislation will protect the people, boost prosperity—and distribute the burden as equitably as possible across the commonwealth. With this context in mind, it's reasonable to assume Masaccio's painting served as both propaganda and a reminder of the city's history, an attempt to gloss over the discontent of the Florentine population with a grandiose work of art, as it were.10

In any case, the Senate’s commission awarded in 1428 for the Mercato Vecchio, a statue by Donatello representing the prosperity and common good of the city, follows this logic. Herein lies the function of aesthetic appearance: on the one hand, the Colonna della Dovizia11 is intended to promote identification with the res publica, and on the other, to make the feeling of personal burden more bearable through shared solidarity. Accordingly, the female figure holds a cornucopia in her arm and carries a basket of fruit on her head – a promise of prosperity in which the city embodies itself. Masaccio's tale of the toll collector's miracle falls into the same register. If the tax collector's demand is heard in such a wonderous way, as the toll collector's miracle suggests, one can hope that the tax will be paid from petty cash.

Subject

Just as Nicole Oresme's 14th century monetary theory develops the logic of a state-centered perspective, the catasto of 1427 transforms the Republic of Florence into a Social Machine utilizing Central Perspective’s linearity. The subject, who, as a child of God, has retained his freedom and autonomy, is subjected to the power of the sovereign as a taxpayer: sub-iectus in the literal sense. And this dialectic of freedom and tribute, Image and Number will accompany the modern subject from now on. The image, which registers every single wrinkle, every physiognomic peculiarity, corresponds to the number on the other side12: the individual, recorded as a bundle of data and integrated into the data corpus of the Republic. Here he’s registered, together with his profession and dependents, as the owner of this or that personal or real estate property, as the breadwinner of this or that bocche, and his tax file also contains his submissions and letters of protest. Because the tax assessors who visited the homes of Florentine citizens from 1424 to 1427 recorded each citizen in a meticulously, almost embarrassingly way; the catasto offers the most amazing collection13 of information available from the Early Modern period. Considering that even in the 21st century, many States still lack a land registry, including Greece, the birthplace of democracy, this fact – namely, the absolutism of social power – is particularly striking. Since citizens weren’t always willing to provide information, measures were implemented that remain part of the tax authority’s core functions today. So while denunciation was the order of the day, with informers receiving a quarter of the hidden wealth –voluntary self-disclosure was rewarded with exemption from punishment; in addition, house searches were conducted, or the accounts of creditors and debtors were compared—all aimed at obtaining as complete a record of assessable wealth as possible. To compel taxpayers to answer honestly, the Senate passed a law on May 24, 1427, imposing Draconian punishments, including the death penalty for particularly serious cases of tax fraud – even though, as a paper tiger, it was never enforced. If Hegel calls the State, as a worthy descendant of the Lord, ›the all-pervasive unity,‹ it can be said that the Treasury, in a similarly radical way, screened the entire Florentine population – in an equally radical way that the visual rays do in physical space. And just as points become isomorphic here, like Leon Battista Alberti speaking of the point as the smallest image size—the atomization of the citizenry creates a need for pronounced tax justice. Taxpayers could claim allowances for bocche, the mouths to feed – with the same applied to production tools, livestock, or cultivated land. A good seventh of the population of Florence was exempt from paying taxes altogether because they were among the miserabili.14 However, this didn't spare them from the burdensome obligation of being scrutinized by the tax authorities. When David Herlihy and Christiane Klapsch-Zuber, who have studied the Florentine Catasto in detail, concluded that »The Catasto scans the land, like the rays of a summer sun,« it can be said in general terms that the beam of authority shines through every Florentine citizen.15 Besides the statistical interpretation, this phenomenon holds significant social-psychological interest. Being evaluated by the authorities based on specific criteria, the individual perceives himself as a data bundle and is compelled to regard himself as an economic unit. In this regard, the wealth of physiognomic detail characterizing the portraits of the time reflects a necessary economic introspection. It's no coincidence that the great Renaissance image theorist Leon Battista Alberti wrote a treatise on the economization of domestic life.

Society Projector

The Florentine catasto is undoubtedly a treasury of insights for the social historian of the Renaissance, but the question at issue here extends far beyond any specific individual case. The simultaneous reference to Image and Number – understood as the Early Modern State’s aesthetic appearance and drive – concerns the modern constitution of the subject in general. This shouldn’t be viewed as the heroic figure of the autonomous subject but rather as a component of an overarching, Symbolic Order, which might be called a Social Projector [Gesellschaftsprojektor]– and what Foucault, lacking a technological reference, termed the Code of Representation – or, even more abstractly: the Dispositif. This question, now of significant political relevance, arises because the binding power of representation has clearly diminished to the point where you can almost grasp the end of this projector. Where society dissolves into a multitude of atomized free radicals, understanding the conceptual archaeology shaping the modern relationship between I and We, individual and society, is necessary. This step is also overdue because the autonomous subject in its post-Modern interpretation seems solely other-directed: a damaged existence that must be shielded from the intrusions of a system of inheritance.16 However, this new understanding of the subject, which has crossed over into victimhood, mirrors the Symbolic Order's denial: that the subject didn't engender itself but is a product of the Central-Perspective’s Social Projector. To gain clarity about the change, the end of Representation mustn’t echo its dark beginnings. Instead, we must consider the Logic of Representation – specifically, as a Central-Perspective Social Projector. What exactly is the nature of this projector? And what are its historical causes? Reference to the monetary issues of the 14th century makes it clear that the Central Perspective isn’t merely an aesthetic technique but a fundamental shift in the social foundation [Gesellschaftsfundament]. The historical driving force of this development is the Wheelwork Automaton of the Middle Ages, which, in its hypostasis as a mechanical clock, revolutionized the concept of time and labor, with which interest unleashed a proto-Capitalist dynamization and monetarization: Time is money—ultimately affecting the very concept of power reflected in how the 14th-century theologians redefined the dear Lord as a watchmaker. It's no wonder that the Social Projector discards repraesentatio's theological interpretation and introduces new social practices. This is also reflected in Masaccio's Tribute Money. Firstly, regarding the understanding of time, Masaccio's depiction shows Peter as a triplet, which aligns with medieval reception logic in contrast to the nunc stans’ logic of temporal compression logic. Consequently, these types of scenes disappear in the light of this time compression logic’s signature[Signatur]—with a signature’s representational marking [Unterschrift] that expresses an individual's enduring identity throughout a lifetime.17 Secondly, there are the disciples' halos, which Masaccio, by following Central Perspective's principles, has adapted to the positions of the figures' heads in three-dimensional space. While medieval painting always employed gold for halos, Alberti encouraged the painter to use various shades of yellow instead to create a more realistic impression. In a sense, natural substance is replaced by appearance - which, following Cassirer, Foucault, in his The Order of Things, understood as the shift from analogy to representation. For much of the Middle Ages, following Aristotle's thinking, it was believed that the individual emitted a visual substance during the act of seeing. This substance enveloped the object of contemplation and reflected a small eidolon back into the brain, where it was once again compared with predetermined images—the divine database, so to speak. However, this emission logic eventually gave way to the assumption that we’re simply dealing with visual rays.18 The act of perception becomes impersonal, thus anticipating the Enlightenment’s [Aufklärung] intersubjective and scientific view. It's easy to recognize how a change in worldview accompanies these shifts in interpretation. However, as the Florentine catasto demonstrates, the altered Worldview Machine isn’t only reflected in the valorization of the cognitive subject but also transforms the political space. Figures of thought that served as theologoumenon in the medieval world become this world’s practical, manageable quantities. The repraesentatio no longer refers to the Oblate, which ensures the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, but instead refers to Thomas Hobbes’ artificial man: the bearer of an office who speaks not with his own voice but on behalf of another. Since all these acts are repeated with every sum of money that changes hands and with every sentence written by a civil servant, society can gradually transform itself à la longue into a Social Machine [Gesellschaftsmaschine] – a Machine whose origins fall back into darkness as it becomes ever more refined. Where the thinking of the Central Perspective establishes itself, there's no longer any need to worry about the intellectual embarrassments of the Middle Ages. If the 14th century grappled with the question of repraesentatio and money, not to mention the anxious, interest-demanding times, capitalism now appears as second nature. As the Treasury becomes a part of everyday life, it absorbs Christ’s image – much like a camera obscura or, more precisely: a black box. In this sense, this social institution acts as a monument to oblivion. Indeed, you could even say that the Symbolic Order’s consciousness darkens directly with the materialization of the Central Perspective Social Projector's figures of thought: within the Treasury, the Central Bank, and through absolutism. In the thought of someone like Thomas Hobbes, the theological contraband of representational thinking can hardly be detected – consequently, he can speak unapologetically of the Logic of Representation.

When characterizing the transition from the Middle Ages to the Modern Era, it's often stated that society became secularized. However, a more precise description would be that the yearning for transcendence was flattened and shifted horizontally, or more accurately: into the image’s vanishing point. The heavenly Jerusalem—which had already materialized in the Gothic cathedrals—transforms into an earthly El Dorado: a social utopia where the desires for free development and social prosperity converge. While the Middle Ages relied on god and substances, appearance has now become a fundamental aspect of society. A clear example of this new social currency is how Pico della Mirandola, in his Oration on the Dignity of Man, locates it in his chameleonic nature,19 thus replacing the cardinal virtues of the Middle Ages (virtutes) with the virtuosity of the character actor. Accordingly, virtù no longer refers to a specific, clearly defined canon of virtues but to abstract potency: the freedom to act in one way but also to behave quite differently. This leads to the split between the inner and outer self, the ›we‹ and the ›I.‹ This division prompts Machiavelli to assert that a prince's political wisdom doesn’t lie in being good but in appearing to be good: »Therefore, it is not necessary for a prince to possess all of the above-mentioned qualities, but it is very necessary for him to appear to possess them. Furthermore, I shall dare to assert this: that having them and always observing them is harmful, but appearing to observe them is useful: for instance, to appear merciful, faithful, humane, trustworthy, religious, and to be so; but with his mind disposed in such a way that, should it become necessary not to be so, he will be able and know how to change to the opposite.«20 However, it would be inaccurate to characterize those who are virtuous in appearance as mere counterfeiters. Au contraire—if we consider Alberti's admonition to painters to use not the substance but a blend of yellow tones to represent gold, we understand that this is by no means a matter of giving a carte blanche to lies but that one must proceed in a highly disciplined manner, specifically in accordance with the laws of the Symbolic Order. Consequently, the appearance of goodness, which contributes to the common good, is preferable to the unreflective kindness of a ruler. What's essential is taking the logic of Central Perspective to heart, the distinction between I and we, and the separation of appearance and substance. Just as the Renaissance entrepreneur, whose willingness to venture beyond the horizon mirrors the taxpayer sacrificing part of his profit for the greater good, the personality splits into two beings. However, because image and number, subject and object, adhere to the Social Projector's logic, individuals must maintain double-entry accounts in both commerce and their psyches.

The Dizziness of Virtuality

That question of the subject's constitution has gained virulence, as has the Crisis of Representation, is attributable to the appearance of a new Universal Machine on the world stage in the form of the computer, which as overtaken the Wheelwork Automaton.21 In the presence of Digitalised Mind-Bodies—which themselves transcend space and time: Anything, Anytime, Anywhere—the Cartesian worldview has proven obsolete, as does the notion that philosophical questions can be dealt with utilizing mind-body dualism. In the wake of this new confusion, unresolved questions from the past resurface 22 as the rupturing of the Symbolic Order becomes tangible. According to the formula of institutions representing solutions to problems no longer remembered, these problems also re-emerge as an institution becomes increasingly dysfunctional and hollowed out. You don't have to look far to see this assertion’s validity. Where Digitalisation has removed the distance in the world, the borders of the Nation become fluid, as do definitions of currency, our concept of work, and the reality of Capitalist production. A telling sign of this crisis is how contemporary diagnostics can only agree on a post-festum, in which we find ourselves in a post-Modern, post-democratic, post-factual world, depending on the situation. Institutions appear more massive than ever as the past casts ever-lengthening shadows in the setting sun’s light. That people can imagine the end of the world sooner than the end of Capitalism says nothing more than the Worldview Machine has reached its end – that the film reel with which society comes to understand itself is running out. Considering the narcissistic inflation of subjective thought, you might suspect a renaissance of the autonomous self, but it seems more likely we're witnessing the last convulsions of representational thinking. The empty Social Projector indulges in sham production: Fictitious Capital is brought into the World. It's no coincidence all of these images produced by this Machine, following its internal logic, are suspended. Or how else can you celebrate uniqueness with a copy-paste?

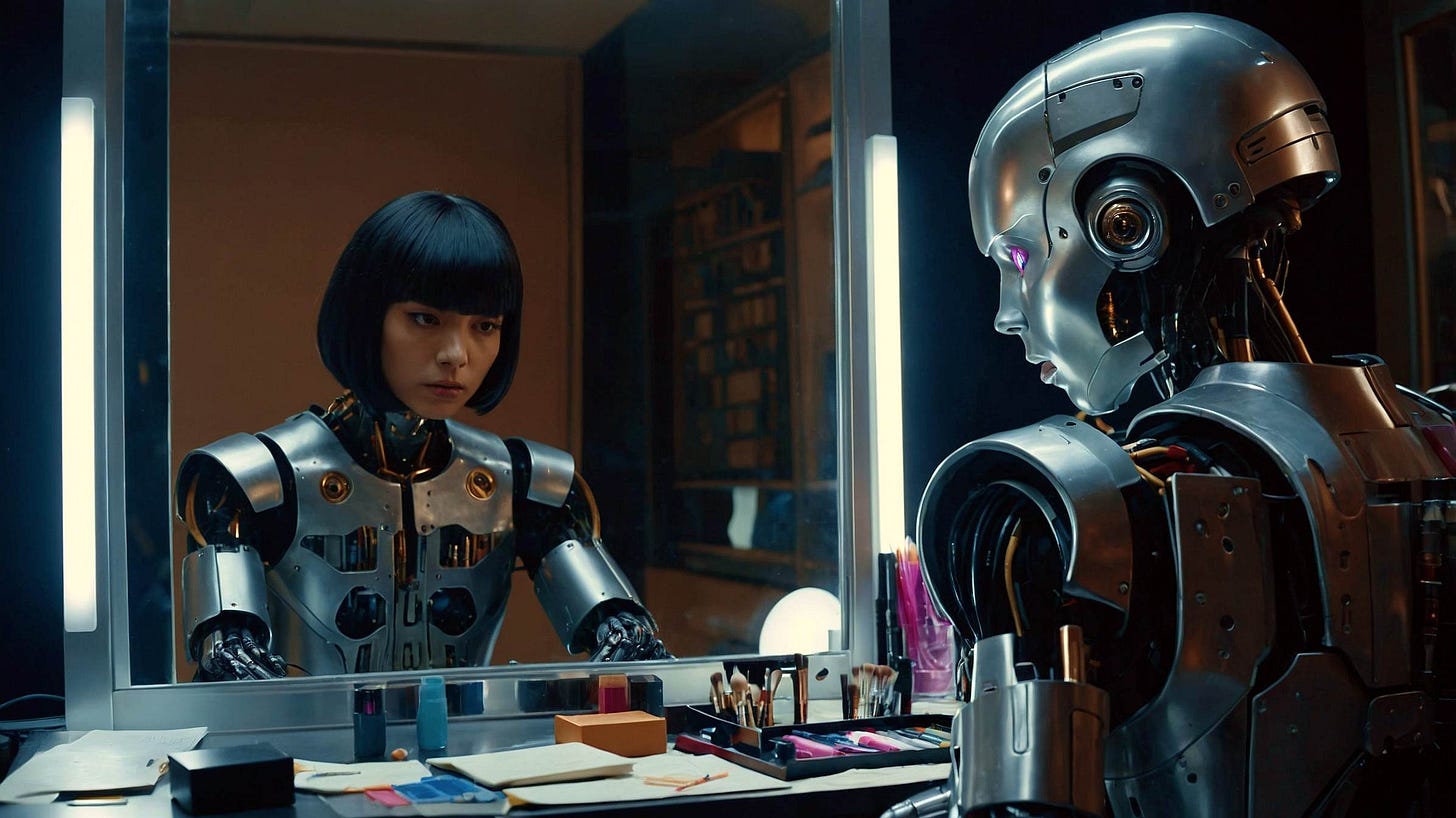

Just as Central Perspective freezes medieval stories into the nunc stans of the eternal present while exorcising the notion of substance, the contemporary projector deconstructs the Social Projector of Central Perspective: the logic of subject and object. In fact, the digitalised driving force not only disrupts traditional assumptions but also introduces new, disruptive principles as a communicative machine. The influencer who shares an exemplary lifestyle with his Instagram community inevitably finds himself commodifying his identity as he adjusts his appearance to the excitation waves of the Attention Economy. In this sense, their engagement can be understood as an act of privation, reflecting a logic of socialization where one's life transforms into a Me, Inc., serving as a social projection. However, this paradoxical approach, deeply embedded in the social self-optimization project, is a source of cognitive dissonance: if the self is canonized as the highest good, it must be treated – in practice – as an arbitrarily modifiable pixel cloud, requiring modeling, correction, and augmentation to meet excessive social expectations. However, since the appearance of authenticity and the phantasm of self-generation are enthroned above all else, the modifications of the self-image mustn't be allowed to come to light—because that would mean defiling the religion of self-realization. Inevitably, a schism occurs between the Social Projector—the general system of expectations—and the everyday practices that have been relegated to clandestine concealment. Now, this schizophrenia affects not only the influencer but can also be read as a symptom of a social identity disorder. Although traditional representative institutions still exist, people may believe they're living within the traditional framework; however, communication acts function under a heteronomous logic. But this leads to a continuous, creeping erosion that isn’t halted by the defiant insistence on political primacy despite an awareness of the loss. If we understand our social system, like the Florence catasto, as a Symbolic Order establishing itself over a corpus of data, then that States have stopped seeking to lead in political economics23 – that is, in the realm of statistics – can only be interpreted as a form of decline. In contrast, the major Internet providers are demonstrating that non-State actors have now created the largest and most extensive data collections—and this digitalised catasto fosters neo-feudal conditions. Now, anyone with eyes to see will recognize this power paradigm shift, but it’s much more challenging to grasp that the crisis phenomena aren’t from random coincidences but the disruption of the SocialProjector. Which of our contemporaries would associate the European Central Bank’s embarrassment, which can only itself with negative interest rates and the prospect of helicopter money, with the disintegration of the self-image? And who, lacking knowledge about Representation’s religious contraband, would be prepared to analyze the current crisis in religious terms? It’s because all these references, still visible at the threshold of the Modern Age, have lost their legibility that there's a reprisal of the Renaissance drama: the schism between the old and new world. Yet, if we imagine ourselves back in the era, the schism of the Renaissance is by no means as clear-cut as the heroic story would have us believe. The year Botticelli painted his Birth of Venus coincided with the year the bitter Dominican friar HeinrichKramer authored his Malleus Maleficarum—the Witches Hammer. And in the same matter-of-factness with which Savonarola utilized Gutenberg's printing press, he also accuses painters of genetically counterfeiting—consigning them to the purgatory of vanity. In other words, the schizophrenia that announces itself in this simultaneity of heteronomous orders seems to be our destiny as well, at least wherever people are unsure about the Social Projector's logic. What a fitting book title that would be: Waiting for Savonarola.

Translation: Hopkins Stanley & Martin Burckhardt

This text has addressed several phenomena that will play a significant role in upcoming discussions on ex nihilo – highlighting questions of Identity (in the Trans debate), Political Representation, and the Common Good. We will also mark another reference point when we publish a work on the shifting from the Visual- to the Acoustic-Worldview Machine.

The Self or Ego [Ich] is primarily seen as the bearer of rights in the political sphere, while its duties to society are much less clear. This reflexion reflects the heroic origin myth.

It's no coincidence that ›worldview disputes‹ have made use almost exclusively of those strategic points well into the present, which only makessense when assumed from the perspective of the image. ›To obtain points of view‹, ›to occupy terms‹, ›to have an overview‹, to illuminate a ›thing in one way or another‹, to bring this or that ›point of view‹ into the debate, to accuse the opponent of a ›limited horizon‹, to accuse him of ›subjectivity‹ and to speak of ›objective conditions‹ – all these are figures of thought that move only in the Logic of the Central Perspective’s image.« See Burckhardt, M. – Chapter 7 Gesellschaft im Park in Metamorphosen von Raum und Zeit: Eine Geschichte der Wahrnehmung, Frankfurt/M, 1994, p. 206

If we wanted to trace the use of the term across various fields – from political philosophy and art to cognition and mathematics – back to a common, original concept, we'd be obliged to distinguish, as Hanna Pitkin does in her 1967 The Concept of Representation, between different social practices: from the logic of representation to authorization, and to representation and acting on behalf of another.

As early as the 13th century, the term res nullius was used to refer to »the things that do not belong to any individual.« De facto, the logic of representation is linked to the development of mathematical zero. Until then, calculations could only be accomplished through analogies of proportions (a:b = c:d), leading to the goal of triangulating the term on the right, known as the representant, which emerged as early as the 14th century—a movement that led directly to the mathematical zero. Oresme is also considered a forerunner here. In his Tractatus de configurationibus qualitatum et motuum, his treatise on the configurations of qualities and movements, he outlines the idea of a coordinated geometric space »Just as zero in the 14th century becomes the pivot of economic activity, mathematics seeks to resolve the dilemma of analogy. This is why Nicole Oresme not only comments on questions of money but also, with the Proportion of Proportions (De proportionibus proportionum), sketches the focal and vanishing point of the perspective image: the possibility of being able to think a new world. This is precisely René Descartes’ novelty: he demonstrates how geometric questions transform into algebraic questions, how a geometric body can become a number or a formula. With this, bodies are no longer understood as prior entities, as in Plato's time – instead, they are seen as structures owing their existence to mechanical construction. In this sense, the Pythagorean dictum – ›All is Number‹ – has become reality: the world, more synthetico, no more than a creation of the mind.« See Burckhardt, M – Chapter 12, Machine of World Domination, Aporism 311 (At the Zero Point) in Philosophie der Maschine, Berlin, 2018, p. 185-186.

Nicole Oresme's work on proportions and money led him to ask: ›Who owns the money?‹ is the starting point of Modernity’s understanding of representation (see footnote 4 above), which will come fully into relief with Hobb’s Leviathan at the end of the 17th century. See Oresme, N. – The De Moneta of Nicholas Oresmé, in The De Moneta of Nicholas Oresmé and English Mint Documents. Translated by Charles Johnson. London/M, 1956.

»The Signs of the Alphabet describe an empty, closed space. This closure has two aspects. First, the physical world is locked out – thus, things and living beings will no longer be able to cast their shadows into this space. Second, the space of the Signs themselves becomes a totality stretching the Cell to Infinity so that the world's exclusion is no longer perceptible. These two interrelated points distinguish the Alphabet from its predecessors: vowel notation and the concept of a system. Because the Alphabet describes a closed cycle, it can absorb the fantasy of the whole (the Holon, the World) into itself. In contemporary terms, we might say the Alphabet functions as a Symbolic Machine. Initially, it may seem irritating to speak of a »Machine« here – although this term is all the more accurate in a decisive sense when we understand the Machine as that which represents a symbolic cycle – which, in fact, is characteristic of everything we refer to as a »System« – and which usually represents only a variation of Wheelwork [Räderwerk] and Control Cycles [Regelkreislauf].

It’s precisely this idea of the symbolic cycle that reveals what myth can only tell us in fragments or dark images: that the hiatus releasing the Alphabet from traditional written forms is precisely how the symbolic, taken entirely on its own, can become a cycle for the first time, allowing the world to be understood as a Machine. Within the circular shape – this distinctive archaic form – lies the incision that marks the Alphabet's special nature. Imagine the circle as a skin, a membrane isolating the Sign from the corporeal world, creating an abstract, symbolic wholeness. This wholeness is, in a sense, something like a cover, a Symbolic Order, under which the physical world disappears in the same way a monk's body disappears under his habit. This detachment from the corporeal world seems essential, not only because it creates a barrier between Thing and Sign as a kind of divider that henceforth divides the World into signifiers and signifieds, but also underscores the inherent change in meaning accompanying the Alphabetic Sign. The system of Signs, set in circular motion, marks a new field: an inner space governed by its own laws. The Labyrinth of Signs. Nothing will enter this closed edifice of thought; nothing will defile the purity of the Signs. From a historical perspective, this is where the final and most significant point comes into play—the point at which the intellect in the Machine leaps into the Religious or – so to speak – into the transcendental. While earlier forms of Writing were exposed to semantic influences that necessitated an adaptation of the Symbolic Apparatus (as exemplified by the addition of a pictograph) whenever there was a change in the outside world, the Alphabet's closed interior space opened up a sphere removed from the World and Time. In sharp contrast to the animal power deities, which die and resurrect with the changing seasons, the assertion of eternity is formed, which simultaneously embodies the idea of comprehensive fertility – as if everything has already been said and everything has already been done. The relationship between Time and Eternity – which Christian Philosophy, together with that of Late Antiquity, would develop as the point of the ultimate hypostasis – is prefigured here as absolute stasis. ›In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and God was the Word‹ (John I, I). The Alphabet appears as a Primal Cell containing the pleroma, the fullness of Being.« See Burckhardt, M. – Closed World, from Chapter 11, The Body of the Sign, in Metamorphosen von Raum und Zeit: Eine Geschichte der Wahrnehmung, Frankfurt/M, 1994, pp. 101-103.

»...It isn’t without a certain irony that the catasto executes precisely the opposite of what the biblical episode sets forth as the normal State. Now, to avoid causing offense, it’s no longer the strangers who are taxed but the Children of the City. This establishes the principle of alterity, which Benjamin Nelson understands as a characteristic of Capitalism. In contrast, Masaccio's fresco portrays the episode in a way that emphasizes community rather than isolation. Jesus stands at the center of the image, surrounded by his disciples, while the act of settling the tax debt occurs at the far edge. On the left, Peter is depicted fishing from a small lake, where he finds the four-drachma coin in a fish's mouth. The city's ability to achieve such a miracle seemingly out of nowhere highlights its community-building function – which isn't only the first painting in Art History to employ a Central Perspective—but also represents the apotheosis of a commonwealth constructed utilizing this technique. On the surface, the biblical episode appeals to shared faith, but its decisive message reveals that the glue of the commonwealth is rooted in money.« See Burckhardt, M – Chapter 12, Machine of World Domination, Aporism 304 (State Machine), in Philosophie der Maschine, Berlin, 2018, pp. 178-179.

Arthur Field: The Intellectual Struggle for Florence. Humanists and the Beginnings of the Medici Regime, 1420-1440. Oxford 2017.

»Profit – our salvation lies in the order of money.«

It’s been objected that Brancacci, who was later exiled after clashing with the Medicis, opposed the catasto. However, it’s also striking that the motifs adorning the Brancacci Chapel all center on the question of exchange.

The Colonna della Dovizia, now known as the Colonna dell'Abbondanza, is that’s left of the Mercato Vecchio. Now the Piazza della Repubblica sits on the original site.

»It's not difficult to see in it the abbreviation of those Mental Machines that are based solely on themselves: Time, Money, Image. In this context (coded by the Zero), the One is the principle of Identity – which shouldn't be confused with wholeness or integrity – and signifies that every equation, every exchange can be resolved into a third, or, as it is termed mathematically, can find a Representative. Differential, Integral. What's reflected here in the mathematical expression’s form is the unmistakable Physiognomy of the Portrait, the claim to uniqueness and distinctiveness, the claim to be ›faithfully‹ copied down to the wrinkles in the skin. In this sense, the rupture dissolving the intersection isn't a special mathematical problem but only an abbreviation for the turning point occurring at the end of the Middle Ages...« See Burckhardt, M. – Chapter 11, The Body of the Sign, in Metamorphosen von Raum und Zeit: Eine Geschichte der Wahrnehmung, Frankfurt/M, 1994, p. 318.

Here is an online database where you can see the wealth distribution of Florence in 1427:https://cds.library.brown.edu/projects/catasto/newsearch/sqlform.php.

See Herlihy, D. & Klapisch-Zuper, C. – Tuscans and their families: a study of the Florentine catasto of 1427, New Haven, 1985

The radical nature of this approach is evident through Cosimo de' Medici's efforts to conceal his true financial circumstances during the second land registry in 1431. See Herlihy, D. & Klapisch-Zuper, C. – Tuscans and their families: a study of the Florentine catasto of 1427, New Haven, 1985, p. xxiii.

Foucault speaks of the subject being an "enslaved sovereign, observed spectator". See Foucault, M. – The Order of Things. An Archaeology of the Human Sciences, New York, p. 312.

This can also be seen in painting. See Das Bild und der Spiegel, chapter 4 of the Metamorphosen on Jan van Eyck in Burckhardt, M. –Metamorphosen von Raum und Zeit: Eine Geschichte der Wahrnehmung, Frankfurt/M, 1994, pp. 104-121.

»In medieval painting, gold is used as a marker of the sacred. Conversely, the Renaissance theorist Leon Battista Alberti instructs painters not to create the glow of gold naturalistically, meaning not using actual gold but instead through chromatic, shadowed yellow tones. This reference is much more than aesthetic advice; it stands for the end of a thinking that thought in analogies and repaid like with like. This Greek substantialism let medieval optics explain the visual process with only a miraculous substance, an ethereal visual substance that envelops the viewed body and subsequently sends back a corresponding image (eidolon) into the eye. There it is matched with a preexistent set of ideas and identified as an object. This substance, as well as the matching of ideas that takes place in the brain, is eliminated with the central perspective. Since, now the rays of vision are conceived as impersonal entities thrown from a light source onto a sensitive surface. This does not necessarily have to be the eye of the beholder, but it can also be the projection surface of a camera obscura. Seeing is thus no longer an act originating in the eye of the observer but fundamentally a mechanical process where the observer can be replaced by an optical device.« See Burckhardt, M – Chapter 12, Machine of World Domination, Sham Production, Aporism 301 in Philosophie der Maschine, Berlin, 2018, p. 177.

»Who then will not look with awe upon this our chameleon, or who, at least, will look with greater admiration on any other being? This creature, man, whom Asclepius the Athenian, by reason of this very mutability, this nature capable of transforming itself, quite rightly said was symbolized in the mysteries by the figure of Proteus.« Pico della Mirandola, G. Oration on the Dignity of Man, 1468, Public Domain.

Machiavelli, N. – The Prince, trans. P. Bondanella, Oxford, 2005, p. 61. Brancacci expresses a similar view: »Multi preter honestatem consuluit contrarium ei quod in pectore tenent«—›many, contradicting the truth, give advice that contradicts what they cherish in their hearts.‹

I have devoted several books to this question of the Universal Machine’s genealogy and its social implications. A condensed version of this can be found in my Philosophy of the Machine. See Burckhardt, M. – Philosophie der Maschine, Matthes & Seitz, Berlin 2018. See also Emergence of the Psychotope, Ex nihilo, Aug 28, 2023.

The mere association of the mechanistic worldview with Descartes marks a problem. The concept of the Machine that informs Cartesian thought was already present in the 12th and 13th centuries thinking, presenting us with the dilemma of either speaking of a »thing without a thinker« or admitting that Descartes was centuries late.

This is the original meaning of the word statistics from Gottfried Achenwall’s day.

Related Content

The Money Mystery

The fact that the monetary order is a mystery even to the majority of economists is perhaps one of the greatest oddities of our time. This is the subject of this interview with Heiner Flassbeck, former State Secretary and long-time Chief Economist at the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development in Geneva. The conversation too…

The Bill of Identity

The following open letter addresses the German Self-Determination Act. Although based on laudable intentions, it does have a few oddities or identity traps that are humorously pointed out. This form of legislation is not unique to Germany, but is globally en vogue (or should one say:

In Foucault's Darkroom

There are thinkers whose philosophy exudes a fascinating, dark aura – and Michel Foucault undoubtedly belongs in this register. While Foucault has become the most quoted intellectual in the West, it is easy to forget that in his day, he occupied an outsider position that was so marginalized that my professor, the good K.O. Conrady, felt compel…

Postmodern Demonology

If, when reflecting on the fatalities of today's culture wars, with its encroachments and infringements by self-appointed language police, we're reminded of George Orwell, of his logic of Oldspeak and Newspeak, thoughtcrime and the Ministry of Truth, it's no coincidence. Like few others before him, Orwell grasped the abysses of totalitarian thinking. He…