A mountain is in labor, then gives birth to a mouse. (Horace, Ars poetica). Which raises the question: What becomes of such a mouse when it grows up?

On December 9, 1968, before the eyes of a dewy-eyed crowd at the Convention Center in San Francisco, a demonstration took place that seemed to many present as a trip back in time; indeed, one writer called it "the next big thing after LSD“. The largely unknown performer Douglas C. Engelbart surpassed everything the computer specialists had imagined in their wildest dreams. In his ninety-minute live demonstration, Engelbart presented not only the first computer mouse, but also a hypertext editor that, in addition to a graphical user interface (with various views), enabled collaborative work on documents. This was followed by e-mails with a link function, statistical plots, expandable and compressible windows, keyword searches and macros, a meta-programming language, and finally an online knowledge repository that served as a wiki and could be edited in real time and from different locations. On a ten-meter-wide video projection screen, viewers could watch an employee in Menlo Park, fifty kilometers away, communicate via headset with Engelbart and jointly edit a data set – while his facial expression was reflected on the screen. The presentation seemed as magical as levitation to the audience. As soon as Engelbart had finished, everyone rose from their seats clapping frenetically – as if the hall itself had been lifted out of its hinges and was rising into the air.

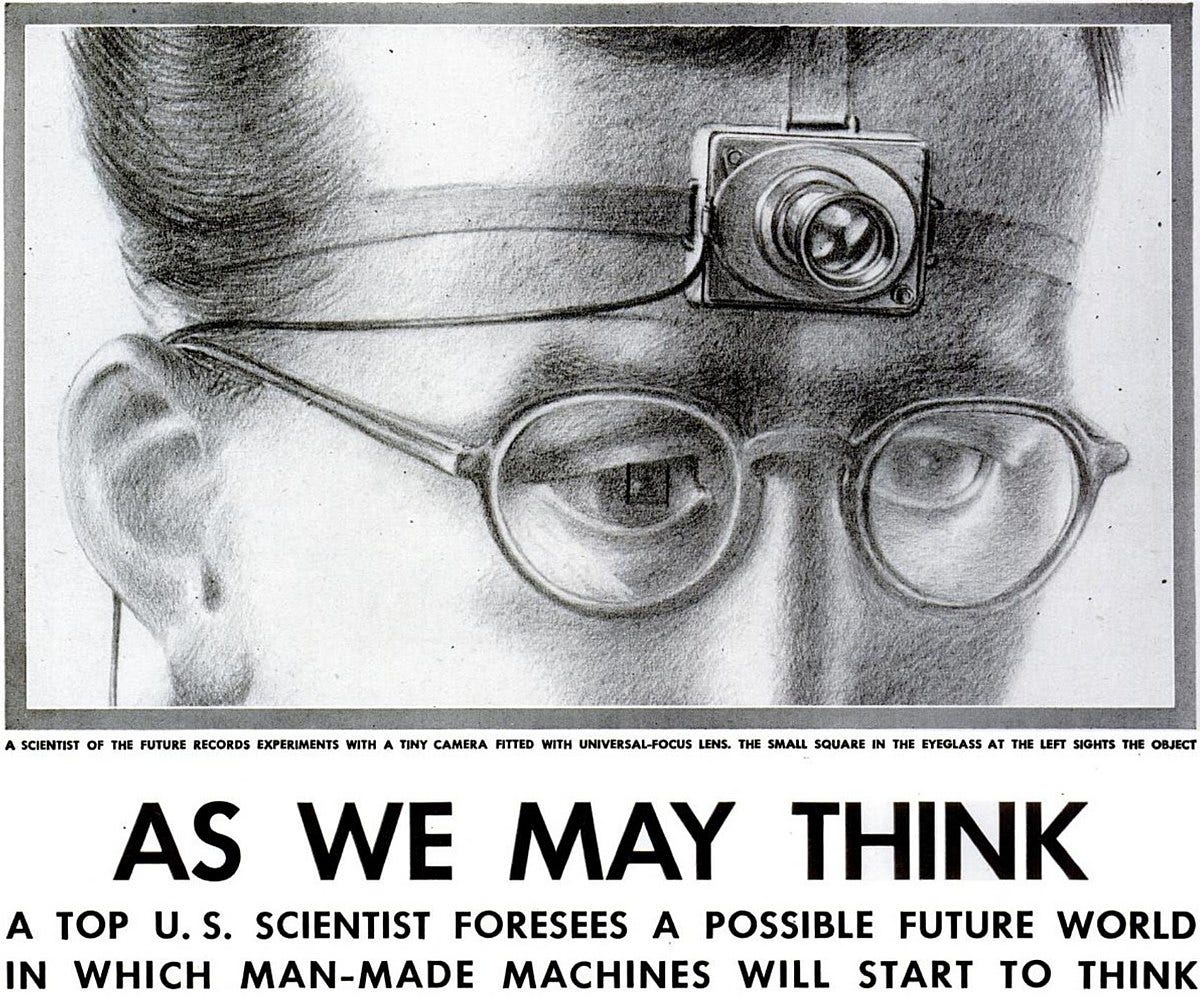

If we review our history, which has stretched over two centuries up to now, we see the computer takes a sudden leap forward. Given the rather slow and deliberate progression of computer technology, the question then becomes what or who makes it take such an accelerated leap? As we shall see, a man like Douglas Engelbart does not fall from heaven, but is deeply entangled in the thoughts of his predecessors. The story begins on a warship about to sail where we find our hero of the following pages. While still in the port of San Francisco, the ship crew learns Japan, in response to the second atomic bombing, has capitulated & surrendered. The crew of course, loudly demanded to turn back to no avail. So this ship sets sail and a few days later moors at a small island in the Philippines. And because the war is over, the young radar technician, Douglas Engelbart has time to browse through all the books laid out there in the Red Cross library. Although the word "library" is a bit exaggerated here as it is only a small bamboo hut on stilts, barely more than three meters in diameter wide. But no other G.I. gets lost in here, leaving the young soldier to freely choose from the limited selection. And so, he comes across a text entitled "As We May Think" in an issue of the Atlantic Monthly.

Haven't we heard about it before? Yes, this is the exact text that Vannevar Bush sketches out his vision of a desktop computer in. That gigantic knowledge machine with which you can find, explore, and link texts within seconds and this thought burns itself indelibly into the young man’s memory.

However, this thought will spark to life in his mind a few years later when Engelbart, freshly engaged, sets off for work. Suddenly he has realized he has no career goals other than a steady job, getting married and living happily ever after. While, on the other hand, he still has half a million working minutes ahead of him. So what to do? Since earning money seems so shallow and insignificant as life’s purpose, he wonders what the greatest thing he could do to benefit humanity. If Vannevar Bush taught us the problems of the world are becoming increasingly more complex and urgent, the solution would not be adding more splinters of knowledge to the world. No, he thought, instead we needed to find the ways and means of orienting ourselves within this increasingly unmanageable chaos of information. Thinking about this, he remembers reading the Atlantic Monthly article and it re-ignites in his head – only now it’s clear Vannevar Bush's knowledge machine will not be an analog device, but a computer, or more precisely: a computer with a visual surface. This surface will not just be able to just display information. No, with the help of the computer, it will be possible to fly through the information – just as air traffic controllers use radar to give pilots instructions for their flight route. To do this however, requires we start thinking of knowledge differently; that we start seeing is as the “world space of knowledge” that we transverse as an infonaut guided by a type of digital traffic control system.

The vision stood clear as a guiding star before his inner eye and from now on, every one of his steps will be subordinated to that goal of easily navigating this space of knowledge. To start with he had to find a job that would familiarize him with computers. Because he had heard the University of Berkeley was getting a computer, he enrolled in the electrical engineering course. But when he naively told his colleagues about his plans, they were anything but delighted. The very thought of letting a person interact with a computer without planning or oversight, or even thinking about using it as a typewriter course training device, simply bordered on blasphemy. But our young researcher is not distracted from reaching his goal by this in the least. So he applies for a position at the Stanford Research Institute after finishing his doctoral thesis, where scientific, military, and commercial applications of computers were being researched. After talking and explaining his ideas at the interview, the interviewer asked him how many people he has talked to about his ideas. When he replies this was the first time he has talked about them, the interviewer is reassured and goes on to advise him not to do so in the future; as it was so crazy sounding that everyone would only doubt his intellect. And he gets the job – and for the next three years he busily works on presenting his ideas in a paper entitled "The Improvement of the Human Mind". Finally Stanford University, with his continued insistence, grants him the opportunity to continue his proposal using Air Force research funding. But not because they believed in his ideas, but as a marketing balloon with Engelbart remaining the only collaborator. When his essay appeared in October 1963, lack of a response from the world of computer science was conspicuous in its absence. Although all the things Engelbart would demonstrate a few years later were envisaged here, readers seemed to lack imagination. Even more daunting than his practical proposals were his philosophical interludes, often ascribing a subordinate role to the machine, and were primarily concerned with the co-evolution of man and machine.

The text of his article attracted the attention of two men in prominent positions: Bob Taylor, a psychologist employed by NASA, and Joseph R. Licklider, who had worked on human-machine symbiosis at MIT and received substantial funding from the Department of Defense. And so, in 1964, to the amazement of his superiors, Maverick Engelbart received $1 million to buy a computer and another half a million to build a staff and advance his goal. Within a short time, Engelbart's Augmentation Research Center (ARC) was flourishing. This had a lot to do with the philosophy that Engelbart called "bootstrapping" – which comes from the act of lacing one's boots, or more precisely, from the momentum with which one lifts oneself up into the air, similar to Baron Münchhausen, who succeeds in pulling himself out of the swamp by his own hair – together with a horse.

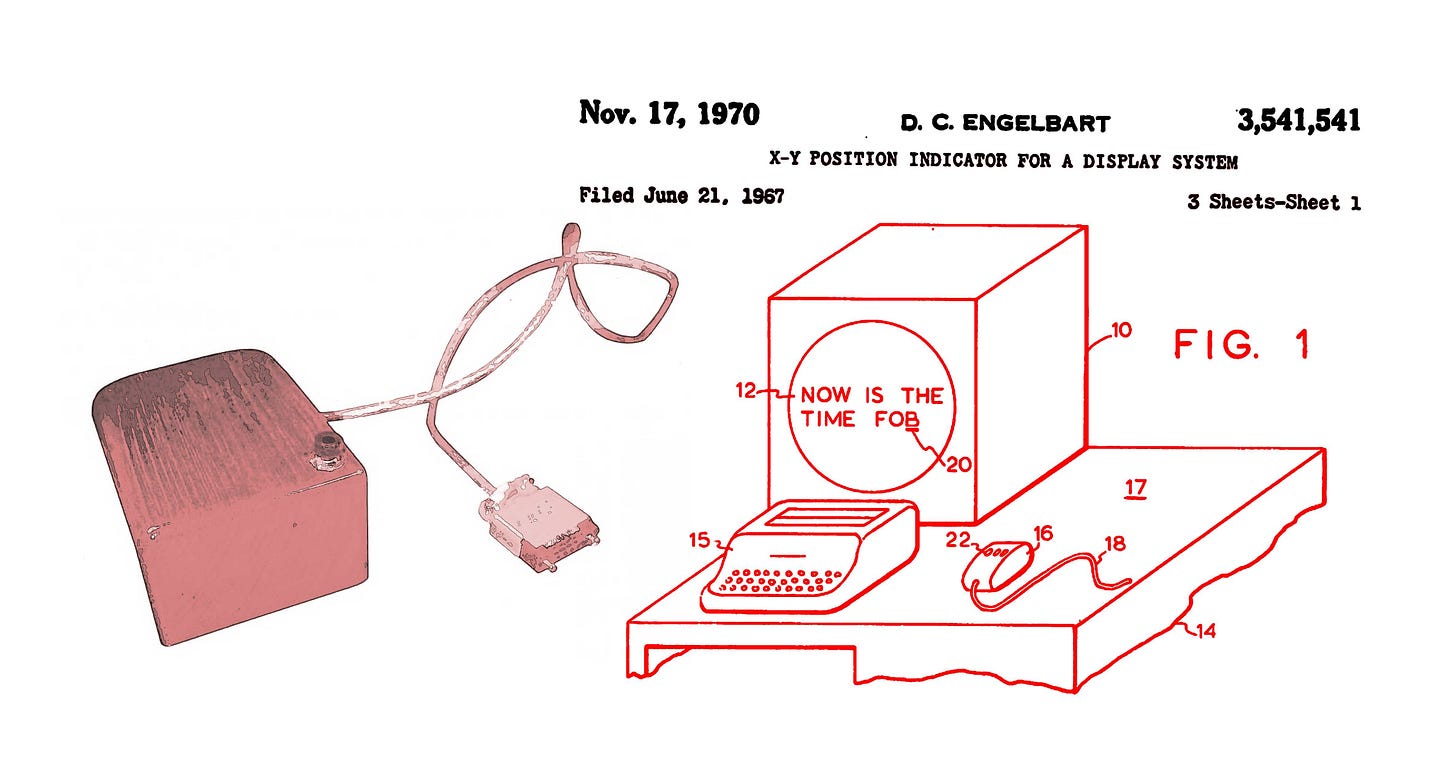

In fact, the most important philosophical insight was tools could be built that could really speed up computer work, and that even more tools to make the computer work even faster were possible. Engelbart also had in mind, thinking about his experience as a radar technician, to treat the screen as a sensitive surface. Why couldn't one point on a screen, like on a blackboard, and leave a mark there? So he sat down and designed a device, equipped with rollers, that transmitted the movement of the hand to the screen. And so the mouse was born.

Now that such a device existed, it was obvious the next step was building the corresponding word processing system so a word could be marked, deleted, or moved with a single click. When Engelbart showed an astonished researcher how easy it was to edit text in this way, the reaction was by no means positive. Quite the contrary, his counterpart insisted that one first had to enter DELETE WORD, then the word to be deleted. Although the mouse may have seemed to be “complicated to use”, the staff at the institute had no trouble at all with it in the least.

One idea after the other was made reality at a breathtaking speed. After the creation of a graphical user interface, it was time to turn to the display in the form of a window that conjured up only a section of the information space on the screen, like the tip of an iceberg. Then came along programs allowing for flight through the data space, like searching, structuring, linking, finally saving and loading sequences of user interactions. To cope with the exploding complexity of the data space, files were created that served as a hyper-texted collective knowledge repository, called a Wiki, that could be commented on and modified as the underlying data changed. Over the years the institute, having grown to seventeen employees, became the first computer-based community, following Engelbart's magical "bootstrapping". They sat at terminals that stood in an open-plan office – or met in the individual offices, where they held brainstorming sessions, sitting on the floor and smoking like an Indian tribe. Not only did Engelbart hire a psychologist to analyze the communication between the participants, but the group also used the consciousness-expanding power of LSD to come up with new ideas.

What looked like creative chaos however was an unprecedented success story – an explosion of efficiency and innovation. It wasn't by chance that Engelbart's Institute became the flagship and the Stanford Research Institute (SRI) the first hub of the Arpanet – just as the institute's knowledge base was anchored in the Online System (NLS) in which Engelbart's dreams of group-based work came true. All the strands of development that emerged in the 1950s – the microprocessor, the general programming language, the idea of simulation – had unfolded an almost revolutionary energy in a manageable group of researchers. The basic condition for this was the generous funding provided by the American Department of Defense, a remarkable funding source because it was not linked to concrete objectives. It was also because, in the spirit of Vannevar Bush, the freedom of research took precedence over everything else. In a strange way, the Stanford Research Institute's Hippie department marks the fulfillment of what Vannevar Bush dreamed of a generation earlier. Only instead of a radioactively contaminated nuclear mushroom, a cloud of imagination rose into the sky. Hardly a generation after Vannevar Bush created the vision of a desktop computer, it has become reality – no, even more, the original vision had been surpassed by reality.

Translation: Hopkins Stanley and Martin Burckhardt

This chapter is taken from Martin Birckhardt’s “Short Story of Digitalization” from 2018

Cyborg Psychology

One of the peculiarities of the Artificial Intelligence Discussion is this conviction that it's only about replacing the human being, while there's hardly a thought given to the fact that what we've put into the world is nothing other than a magic mirror reflection of ourselves- and that this instance will necessarily change our self-image as well.