The Guillotine

A Reflexion on Death Technology, Rationalization and the End of Representation.

Introduction:

This lecture is the 7th in our translational series of Martin’s early works, which he gave to the Guardini Foundation in April 1996. In terms of placement in our timeline to date, we began with Digitale Metaphysik (April 1988), followed by In Working Memory (initially published in January 1990), and Die Universale Maschine (December 1990) – all of which proceeded publication of his first major work: Metamorphosen von Raum und Zeit: Eine Geschichte der Wahrnehmung in 1994. Next in our series is the Portrait of the Author, Electrified: On the Transition from Mechanical to Electromagnetic Writing, presented in November of 1995 as part of the Berlin Radio Play Days1, followed by this lecture on the Guillotine presented in April 1996. After that was the publication of his second major work, Vom Geist der Maschine: Eine Geschichte kultureller Umbrüche, in 1999, which is followed in our series by From the Abuse Value (originally the lecture Zeit ist Geld ist Zeit, presented at Evangelische Akademie Tutzing in 1999). The Monster and its Telematic Guillotine (originally as Das Monster und seine Telematische Guillotine in November 2000, then as a chapter in “68. Die Geschichte einer Kulturrevolution2 in 2009).

The Guillotine, like the Author, Electric, was written when Martin found himself in a place of transition. Up to this point, he hadn’t considered himself or his work as dealing with the theoretical; rather, he’d been asking a series of practical questions that had relieved themselves out of the various artistic problems he’d encountered along the way. However, after the Metamorphosen’s publication, he realized just how far his simple questions had been leading him further and further into theory.

After discovering the Universal Machine, he’d found he had three conceptual movements he needed to write about: 1) What is the horizon from which our digital natives sprang 2) How, in this unfolding of the Sign from representation to simulation, has the conception of writing and the question of authorship changed? 3) In what form does the time rift appear in modernity?

It was how the French revolutionaries had proclaimed a new era when they put the guillotine into operation that brought these questions into such strong focus. Bearing in mind that the concept of authenticity goes back to the Greek authentes, which means both the author and the murderer, the story of the guillotine suggests the disconcerting idea that we are dealing here with an act without a perpetrator - which casts the intellectual contingency of modernity into a new light.

Examining his writings following this lecture, it was surprising to us both just how much Martin had been thinking about the Guillotine. Placing it in context, he’d been deeply involved with the German translation project of Guy Lenôtre’s The Guillotine and the Executioners at the time of the French Revolution3 by the publishing house he’d founded with his younger brother Wolfram, having written its post-script. In a quote from the introduction of our German posting of this lecture, he describes his state of mind at the time:

When Meister Eckhart formulated the beautiful thought that God is simple, he meant that every complex system can be traced back to essential insights – and thus, it turns out to be what Thomas Bernhard summarized in a beautiful title: Simply Complicated. From this vantage point, you see a certain simplicity in every system of thought - which naturally also extends to our own thinking (how could it be otherwise?) That's how this lecture from 1996 links the idea of the temporal rupture with the Guillotine incision - an experience owing much to my involvement in the German translation of Guy Lenôtre's ‘Social History of the Guillotine;’ a book that, precisely because of its physical conciseness, has given me my view of modernity, but also of our contemporary rationality with the unconsciousness of its abyss. And it’s because the times have created their own Telematic Guillotine from our Attention Economy fed media – and because the first welfare committees being formed by its underlying Moral Economy – that this memento appears here…

While this description is wonderfully succinct for the German reader familiar with all of his works, what struck us was the importance of this lecture and the Electric Author for an Englisch-reading audience that wasn’t aware of his works and hadn’t grown numb to his words. They’re both watershed moments for understanding how Representation’s End has unfolded in the interregnum of the Metamorphosen and Geist der Maschine within his thought Labyrinth. Both the academically-minded and the astute reader will notice, when read in succession with From the Abuse Value and The Monster and the Telematic Guillotine, that these lectures portend what we now know as the Attention Economy. In particular, how Abbé Carrichon’s story captures the moment when representation’s notion of Central Perspective becomes transformed into Modernity’s post-truth as a simulation – as Truth is in the Eye of the Beholder – how Truth becomes numbly absorbed into the rhythmic, headless gaze of social masses mesmerized by its temporal rupture, which leads us to our own personal question of what Ethics look like in a post-Atheistic age where an Attention Economy now drives Capitalism.

The Guillotine

The Connection Between Death Technology and Rationalization

Given to the Guardini Foundation in April 1996

Ladies, Gentlemen,

Today, I would like to tell you something about the Guillotine or – as it’s so jarringly presented in the subtitle that even I stumble over it – about the connection between death technology and rationalization. If I'm stumbling, it's safe to assume you're not doing much better. And when I put a word like death-technology into my mouth, it’s not astonishing that you stumble, too. So you’re probably wondering how the Guillotine, that sinister instrument taking us back to Modernity’s threshold, relates to our topic: Time.

Another title I’d had in mind that could have more clearly marked the relation to our topic was a temporal rift [Zeitriß]4 – and the idea behind it that sometime in the late 18th century, Occidental thinking underwent a profound upheaval. Of course, this isn’t new – we’ve founded a whole series of revolutionary formulas for it, such as Human rights, the Industrial Revolution, and even the very concept of Modernity – and all of these formulas say nothing other than: New Times. This is what the French Revolutionaries were attempting to stage as the first year of a new calendar with great fanfare by dispensing with the Christian calendar, as they proclaimed that terrible year of 1792 when the Guillotine also took up its duties – thus marking the beginning of a new time.

However, what I am concerned with, and why I’d like to return to the Guillotine’s timeline, is for something else: I’d like to look at the time of the revolution anew: inverting it as a revolution of time. If you hold a Guillotine in front of your Eye, you will immediately recognize, with me, that the term time rip takes on almost a metonymic dimension here – ruckzuck5, and then it happened. The time of the revolution is really a revolution of time.

Here, time does not take on the abstract, metaphysical dimension that a concept based on the natural sciences so readily accepts, but time is understood as a specific, personal time. And that means: at the same time, it’s both historical and personal time. And if I hold my head under such a knife, it’s my time that tears – and I take that personally.

So I want to write time back onto the body – which is what everyone who attaches a gearwheel clock or one of those digital, quartz-controlled6 wonders to their wrist does. When I talk about time, I’m essentially talking about a time technology – about how I deal with my time. It's here, I claim, that a rift runs – a rift that runs through our present – and through mine. That’s the meaning of this convoluted title: temporal rift [Zeitriß]. Perhaps – and here lies my having relied on this stumbling of thought instead of choosing this snappy title – one of the essential problems of Modernity is that it’s simply progressed over this smoldering threshold and not stumbled, as would have been appropriate. That’s how it’s left us Postmoderns stumbling about in retrospect to this progress of ours, which actually means: a failure to stumble.

So, the Guillotine – who doesn't stumble when it comes to death? Everyone, we would say, but that’s not entirely true. For there are people engaged in the professional business of death: dealing with its particular technological requirements without stumbling, using a sure, prudent hand – the Executioner as our exemplary.

The Executioner's position is already very interesting. For instance, why does a phrase like death technology cause us to stumble? The reason for this seems very simple to me, and it becomes even much simpler if we don't speak of an abstract technology but of its embodiment. So it's the Executioner who operates on the threshold between life and death, reminding us that all technology, as the philosophers say, isn’t just an inner-worldly phenomenon of immanence – it also provides the ways and means of transporting us Out of the World. This means technology always has the problem of Transcendence on its neck, perhaps to the extent that it decides on life and death – today even more than ever. For a long time, this power to touch the transcendent was reserved for the role of the Executioner – and, understandably, thaumaturgic and miraculous powers were attributed to the Executioner and the blood of his victims.

Either way, the ‘Executioner role’ marks that outer edge of reason insofar as he incarnates the death technology in himself as where death is pronounced and executed. And he uses specific techniques – that is, the Techniques of Death.

Insofar as the establishment of the Guillotine is already elucidating – we’re at a critical border, a suspension where a transformational shifting takes place. Normally, as I said, ‘in the belief in progress, we pass over such things’ – indeed, in the foresight of Progress, ex definitionem, is such a disappearance of the borders – only that here, at the border of death, we may hesitate to speak of progress.

Nevertheless, those running the business of death are strangers to such scruples. Like any other tradesman, they wonder whether this or that detail of their activity couldn't be made a little more comfortable. In this sense, the Guillotine is undoubtedly a step forward. Now, I don't want to bother you with too gruesome details – but – I also don't want to withhold from you a passage about the Reasoned Opinion on the method of decapitation, written by Dr. Louis, the permanent secretary of the Academy of Surgery.

We should here recall the facts observed when M. de Lally was beheaded: he was on his knees and his eyes were bandaged; the executioner struck him on the neck; the blow did not sever the head, nor could it have done so. The body, which had nothing to oppose its fall, was overturned forwards, and it was only after three or four blows of the sword that the head was at length severed from the trunk: this hatcherie—if I may invent the word—this hacking to pieces was witnessed with horror.7

There, you can see that a phrase like death technology has its justification. It was – and this was the famous philanthropist Doctor Guillotin’s argumentation of recommending this device to the National Assembly with the somewhat clumsy argument: ‘I'll chop your head off in a twinkling of an eye, and you’ll feel no pain at all’ – the higher, human-friendly reasoning of using his prosthetic hand which convinced the deputies. Thus, assuming the credibility and integrity of its philanthropic name-giver, the Guillotine can now truly be seen as a technological blessing – at least if we look at the technology of death in the abstract.

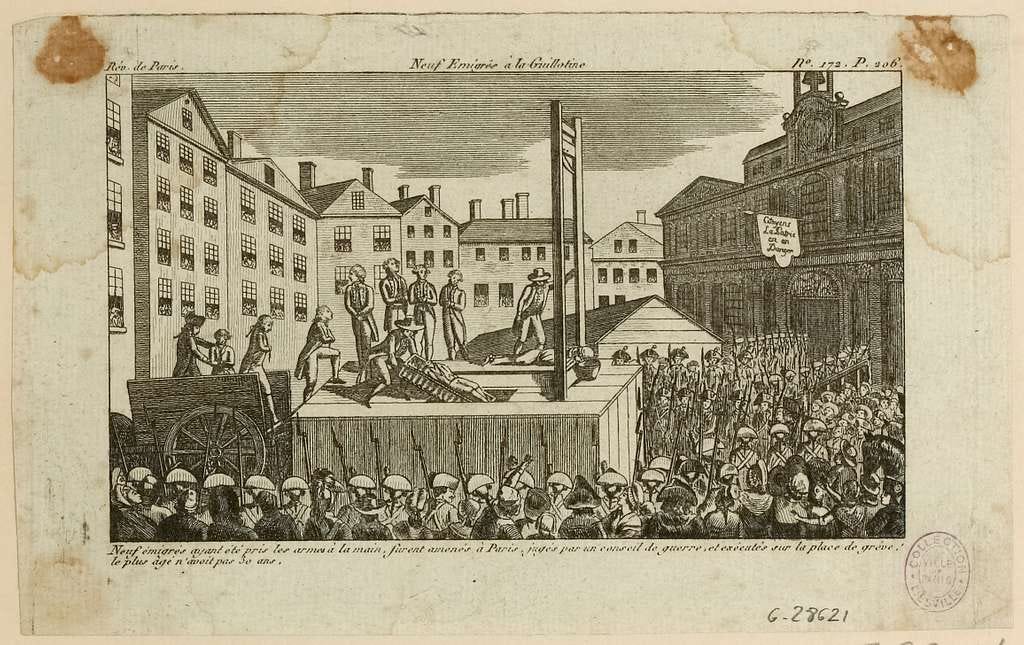

Now, as we know, it isn't that easy to implement any technological innovation. When the Guillotine was ceremoniously inaugurated on the Place de Grève in March 1792, the public, which had flocked to the site in large numbers, was not taken with it. The spectacle was simply too short, the agony of the victim hardly perceptible – and so the mob, who felt cheated of their thrilling, cathartic effect, subsequently ran through the streets bellowing they wanted their good old gallows back. (Whereby the French word for the gallows is potence, that is, virility – to which we’ll return, in connection with the disempowered authority, the King).

As a spectacle and a popular amusement, the Guillotine was a flop. Only when the process became serialized, and head after head began to roll, did the population begin developing a particular taste for the thing. As an exemplar, a restaurant was built across the street from the scaffold, where the menu listed not only the food but also the expected victims. As I said, we're dealing with a dialectical entanglement that the well-meaning doctor may not have had in his Eye. For it was precisely through the fact that the Guillotine, in no time at all [Ruckzack]8 and quite serially, rolled head after head that it made the terreur, the mass murder, eaten as a side-course, possible in the first place.

It was only through this repetition that that titillation, which the gallows used to be able to satisfy, was mediated – and indeed, something new arose, something that has much more to do with the film cut, the rhythm, the scansion. Now, this comparison between the cinematic image and the Guillotine may seem to you like mere metaphorical parallelism or, on the contrary, so obvious that it seems almost improbable recurrence yet again. Who isn't confronted with a scene’s clapperboard rushing down like a Guillotine and announcing: Scene Anyway, take one – and, when it's successfully in the can, it's laconically said, Died – the next one, please!

Of course: if you're dealing with the early days of the cinema, and that actually means: the photographic image, the historical – the structural parallels become much more obvious. Just as the primary concern of the Guillotine's designers was with the physical fixation of the patient, so too were the first portrait photographers concerned with directing the body so that the camera's shot would catch it. In other words, the Guillotine was, in a certain sense, the first cinematic cut because only it could record in real time what the world of technical images could record much later.

Let me tell you a little story that I learned from Guy Lenôtre, a French historian who wrote a wonderful book about the Guillotine at the turn of the century.9 I'm going to digress a bit in this part because it's a very strange story, and it's one of the few stories bringing into relief what was then happening, so I'm going to take this time to tell you about it. It is (keep in mind) about the Eye, the I, the Ego10 . The hero of this story is Abbé Carrichon, a young Oratorian priest11 with an aristocratic family attached to him, which he’s gone into hiding with in Paris in 1794.12 This simple, sensitive soul has promised the Countess of Noailles, her daughter, and her aged mother-in-law, who has already become senile, that he’ll give them absolution when the time comes. And so as not to appear as a priest, he’s also agreed to dress in a dark blue tailcoat and a red vest.

On the morning of June 22, 1794, on the day of St. Madeleine, the time had come. There’s a knock at the door, and the family's tutor is at the door, together with the unsuspecting and cheerful children – who are about to become orphans on that day – who announce that the time has come. Even though Abbé has known that this moment will come, in the blink of an eye, its reality hits him suddenly – and what hits him the most is the pending encounter with the scaffold. As I said, he's a very sensitive soul, and the thought of seeing blood is a headache that won't let go of him. Like a ticking clock, he changes his clothes; letting nothing indicate he’s leaving, he goes to the Revolutionary Tribunal; he then goes to the church where he has a friend prepare him a coffee to help dispel the headache; he then goes back to the palace, with the desire not to arrive, not to meet those who ordered him there. The courtyard of the building is closed, yet the movement inside announces something is about to happen. The first cart drives through the gate – and the Abbé discovers the old, childish marshal is sitting on it. Her daughter-in-law and granddaughter aren’t there, and he gets hopeful – but then, on the second cart, he discovers them: the mother in a blue and white striped robe, the daughter in the white dress she’s not taken off since her father's death. The two carts stand in front of the Palais, exposing the about-to-be-deceased to the mob’s insults for a quarter of an hour as the Abbé tries to make himself known to his confessors – but the mob is too thick, he can't get close enough to them – and they don't see him as the wagons start to move. He wanders through the crowd and makes a big detour to a place where he can sit on a bridge where he thinks they must see him. But in vain: ‘I did everything I could. From everywhere, the crowd is getting bigger and bigger. I am tired. I will retreat.’

In the blink of an eye, a thunderstorm breaks out. Within seconds, the streets are swept clean, and Abbé Carrichon, soaked with sweat and rain, manages to make himself known to the ladies. Running behind the cart that’s accelerated its journey, his head protected against the falling rain, he gives them absolution. And he, whom the fear of the scaffold has been haunting all day, could now turn back…

But strangely: he follows the procession to the place du Trône, where he sees the scaffold that makes him shudder as the rain has stopped, a large mob has gathered – strangely: now the Abbé’s narrative shifts in tone...

While waiting in front of the Palace of Justice was a kind of rumination turned inward, a cramping thought in which he’d been unable to think of anything but the passing of time – another two hours, another hour and a half, another hour, a milky dim fear clenching itself into a headache: he steps out of himself. Now that he's fulfilled his promise, now that he's given absolution, he too is absoluted – absolved. He is now all Eye, and to see better, he changes places. ‘I see the Executioner Master and his two assistants. One of the two assistants stands out because of his size, his fullness of body, the rose he holds in his mouth, the cold-bloodedness and prudence with which he acts’ – and like a Camera, his Gaze captures everything, ‘the rolled-up sleeves, the curled hair tied back in a ponytail’ – and so his Eye notes, with a certain admiration, how precisely all this is going on here, how gentle the torture actually is – horrible only because of the quick succession of blows – so he sees how the first sacrifice is carried out, sees how quickly it’s done, sees how an old man with white hair is led up to the scaffold, sees how he’s supported by the two assistants – who, by the way, are quite respectful and deferential – sees how they tie him down, how the blade rushes down, how the head plops through the hole in the floor into the bran sack, sees how the headless body is turned onto a tipping cart, where everything is swimming in blood – and he sees how the Countess is led up third in the series, sees how, in an attempt to expose her slender neck, the hood is torn from her as it’s fastened with a pin in her hair, she’s pulled by her hair and the head of the Countess is torn off – he sees how the daughter, after the mother has been removed, takes her place, he sees the streaming bright red blood shooting out of her head and neck – and all Eyes, he can't help but watch as he sees how the next victim is led up and he looks and looks until he notices that he has become cold and numbingly frosty. This in the blink of an Eye moment has lasted twenty minutes – and in these twenty minutes, the serialization of the scene was repeated twelve times.

This Gaze of the priest, that looks over-it and forgets himself, seems to me to be essential: it’s in the Eye of the Beholder that lies the temporal rift [Zeitriß] I am concerned with. For he, who’s wanted to assist another person with his gaze, experiences that this gaze forgets itself – that it becomes rigid and cold, that the place of contemplation, you could say, leaves the interior of this sensitive soul, that this Machine operates it remotely.

All Eye, like a surveillance camera zooming in closer and closer to the object of observation, watching the death of those people which, merely imagining it a few hours ago, made him panic – he sees the pain the Executioner inflicts on his confessor's child with the hairpin – but all this doesn't really reach him. It reaches him as an unreality, consisting of the fact that life and death are separated only by a short, precise cut, an eyelid movement. There is no transition here, no more dying.

And as if to convince ourselves that it is nevertheless so, this blink of the Eye is serialized. Death's not-being-able-to-see-more marks the transition into unrealness. Death becomes a film, a thin, un-real layer. Where the Guillotine, as I said, structurally anticipates the film cut. – Hitchcock, if you'll allow me this short bow, knew this precisely: because in Psycho's famous killing scene, you don't see the knife penetrating the victim's body – no, the violence of this murder inscribes itself on the Eye, in a hundred cuts, for a scene that barely lasts a minute and a half.

You see, we are in the middle of it, in the double-edgedness of our subject, exactly there, where we get to the edge of reason – in the same way as our priest falls into his stupor. And this brings us to the connection between death technology and rationalization. The Guillotine thereby leads us into that mental darkness of the word itself. The ratio, consulting my Latin dictionary, is the Business, it's the method, my way of proceeding, and it's finally the reason itself; and because this reason’s engaged in the business of dissection, we’re dealing with a rationalized reason, decomposed into individual portions: a rationed reason, which at worst can change, become a false form of rationalization. Whereby, at the end of this increasingly headless reason’s scale, there’s that use of the word which says it's been somewhat ratiocinated away – meaning, and this is remarkable, that in this form of ratio, you can see here there are no small, but also no big heads anymore – only an abstract, masterless ratio: a large roaming blade, a Mowing Machine.

It's this darkness of our ratio that led me to explore the Guillotine, this other side of reason. Above all, it was essential to escape the configuration between the apologetes and the apocalyptics, between enlighteners and counter-enlighteners – and to understand as one what is one. Here lies perhaps one of the greatest nativities: as if our ratio were a thing that we actually have in our grasp – and as if it weren’t exactly the opposite, that our ratio also has us in its grasp.

Incidentally, one of the paradoxes of our history is that the profession of the Executioner has fallen victim to this Machine's rationalization. It may sound strange, but using the exemplary of the Guillotine and the Executioner, we can re-trace an almost classical case of rationalization. Contrary to our assumptions, the Revolution was not a great time for the Executioners, but rather their downfall.

In the ancien régime, just about every village had its Executioner. These executioners were granted all sorts of privileges whose origins can no longer be traced but probably date back to the end of the Middle Ages. Besides the right to seize dead horses, the most important was the so-called havage13. This meant that the Executioner, equipped with a large sack, could go to the marketplace and claim as much of the goods for sale as he could carry. To mark that he’d already helped himself to a particular merchant, he would draw a cross on his shoulder with a piece of chalk – a procedure that aroused displeasure in the 18th century as people became more sensitive. The curious thing about this large, widely scattered band of Executioners was they suffered from what today would be called covert unemployment. They had so little to maintain their skills in death technology with that they allowed themselves to be credibly released on the grounds of ineptitude and inexperience when the revolutionaries needed them. Of course, this wasn’t too bad since the business of death could be conducted just as easily and even more efficiently with volunteers and ideologists.

It’s at this point that we might pause. That the Executioner is less efficient than the Machine, it’s one thing that the Guillotine does this cruel business more precisely than a sword-wielding hand – and quite another why the ancien régime could afford the luxury of a vast, idle Executioner's staff. Here, we come to an essential question. Evidently, it wasn’t until the middle of the 18th century that the first complaints were heard about the Executioners' privileges. The Executioner was there, that was all – probably no one thought of lamenting his lack of efficiency, as it’s genuinely an absurd thought.

The fact that such a thought arises at all is due to the Machine. Only with the Machine does a concept like energy really make sense; only through such a concept does it become possible to think of man as a thermoelectric Machine. But this is a historical category that must be read, as such, against the background of the steam engine– no slave-owning society would have come up with such an idea. And so the documentaries of the revolutionary tribunals teem with references to how proud people are that the little machine runs like clockwork.

You see, now, if I, regarding the Executioner, introduce a term from our contemporary economics, such as when I speak of ‘human capital’ or even the destruction of human capital, I get into quite a lurch. What, pray tell, does human capital mean here?

Coming now to the most prominent Guillotine victim, we approach the image of the beheaded King. Imagine the procession carrying Louis XVI to his grave in the Madeleine cemetery. There is no service – instead, a regiment plays revolutionary songs. The King lies in an open coffin, his body dressed in a white lace vest, gray silk trousers, and gray silk stockings. He has neither shoes on nor the small tricorn hat with a cockade on it that he‘d worn on the way to the scaffold. His bareheaded head is between his legs; his Eyes are open. And this is precisely how he is buried: the open coffin is lowered into the grave, and unslaked lime is spread over it.

Isn't that a strange picture? If we follow the philanthropic motives of Dr. Guillotin, who praised the humanity of his machine to the National Convention, doesn’t this picture seem even stranger? Why, we might ask, did the revolutionaries have to exhibit the headlessness of their sovereign so graphically? Perhaps we might conjecture because they wanted to demonstrate that the time of his potency was over. But then: Why didn’t they at least give his head, which had been separated from the torso, the honor of closing his eyes?

You see (and you can guess why I've told you the story of Abbé Carrichon): in the dead, glassy Eyes of the king, we have the simulacral after-image of that stupor, as if the dead man is supposed to reflect the event’s dissociative gaze of stupor back to his murderers and witnesses; like a frozen film image: an image in which the viewer recognizes himself – which makes visible the act to him with the speed of its quickness and the abruptness of its cut...while giving him feeling for it – that this death really happened...that the Guillotine performs this transition from life to death in real-time.

Now, no matter how this may be – and we will come back to this - one thing is certain: it’s without a doubt that the Machine's rationality is counteracted in this funeral ritual. Just letting the bright lamp of enlightenment shine here is an inadmissible blending of that cast shadow. You can't simply pass over such a picture; you will stumble. Here, rationality reveals itself in its double-edged form, of which we don't want to know anything if we only chant human rights and Enlightenment.

The Guillotine, as I already mentioned, is a serial machine - which brings an essential reinterpretation of death. Because from this time on, death is effectively serialized. But in the serialization of this process, the respective death is also erased. As such, the headless King also marks the death of sovereignty, leading us to another characteristic of the Guillotine – it gives us a much more complex automaton prototype that modernity subsequently provides: an automaton that no longer needs a human being but functions for itself. It's precisely this aspect that the philanthropists and Enlightenment thinkers noticed so clearly: that with this apparatus, no one will sully their hands by the death of another. Because the ratio of the Machine exculpates whoever starts it up, as he doesn't have to feel that he’s getting his own hands dirty.

This is a leitmotif of our ratio: the deed without the perpetrator. And perhaps this is another reason no one pays that last honor to the King's body. Where the perpetrator disappears, the victim also becomes invisible. Or, more precisely: it becomes an ‘object’, a victim-performer.

As exemplarily, under the proconsul Joseph Lebon’s rule, who’d erected the Guillotine in front of his playhouse so he could witness his theàtre rouge from the balcony – or occasionally when he felt like using the sinister backdrop to intoxicate himself with a speech about the Fatherland.

Now, this may be perverse, but if so, then this shadow also falls on a whole series of figures of thought that are extremely familiar to us, even highly esteemed. The crime without the perpetrator belongs to the image without the image-maker that’s the camera's gaze – distinguished precisely by the fact that it’s incorruptible: objective. The reference to ‘an objectivity’ of whatever kind also carries a knife with it, only that this knife, just as the doctor promised, cuts off our heads, and we don't suffer. Now, I don't want to pursue this strand further, other than pointing out in the disappearance of perpetrator & victim, that a leitmotif resonates whose cataclysms reach far into our time. Yes, I’d even go so far as to locate in the image of the decapitated King a new image of man – the modern di-viduum.

At this point – in order not to lose myself in a vague, theoretical somewhere – I'd like to tell you a second story, reaching back deep into the 18th century. So, this story may appear to have little in common with the Revolution, but it gets there by returning to the beginning of the sensibility narrative. It’s the year 1746 in a big empty field (which I imagine to be like one of those war cemeteries in Normandy, only without the crosses); it’s early morning, and an Abbot’s instructing seven hundred Carthusian monks to line up in a circle; the circle is enormous, a few hundred meters in diameter, but the monks can still see each other. The monks, silently as their order dictates, begin wiring themselves to each other with iron wire. When this is done, the Abbot touches a container wrapped with metal foil, inside and out; it’s filled with water and has a small wire inserted into it, looking like a small, homemade antenna – and, in the blink of an eye, as the Abbot touches this container, something strange happens, something deserving the name temporal rift [Zeitriß] because the seven hundred Carthusian monks all begin to twitch simultaneously.

Now, this act isn't an obscure rite – rather, it’s a scientific experimental procedure designed to determine how fast electricity runs as its question – and the answer is clear. The electricity flows so fast that it can't be perceived with the naked eye; there isn’t a time flow here.

But there's more to this experimental arrangement – it's nothing less than the phantasm of Modernity. Here, we have the man in the crowd; we have the idea (or better: the phantasm) of what’s today called the public space; we have the flow of energy as the mass medium of electricity; and we have the archetype of what can be called the aesthetics of shock. And finally, we have the sensation of synchronization through space and time: what we call actuality – and what can be called the 'distance of distance': Right Now, Live in New York....Here lies the archetype of Modern Society, what in the 19th century will then be called Nation or Public– and today, in a more austere sense: communication and membership. The sensation of being plugged into the same cycle. This is what’s conveyed to the monks (and what had never before conveyed so intensely): Synchronization, the certainty of forming a collective body.

From now on, society hangs in the net; it's electrified. Perhaps the King and the Executioner had already died on that day in 1746, long before the turmoil of the Revolution. For they are necessarily foreign bodies in a world where One-is-plugged-into-the-Other – where all are hooked up to the battery of the masses – perhaps this is what the French revolutionaries were really celebrating when they inaugurated the feast of the Supreme Being: not man, but the battery that gives him the sensation of being One-in-the-Other. Liberté. Egalité. Fraternité – whatever it may be. In this context, where One-is-in-the-Other, bringing a historically powerful, autonomous subject into play is pointless.

When I quoted the image of the decapitated King earlier, I didn't mean a certain Monsieur from the House of Capétiens, but the King, whom we’ve read as the Representative of a Collective Body. The King, Mirabeau aptly says, is the Idol of a collective body – as such, it clings to him as an image that society makes of itself, which is the very meaning of that famous remark uttered by the grandfather of this King: L'État, c'est moi.

If there is a reading that I'd like to recall here, it is that of Ernst Kantorowizc's The King's Two Bodies, where we can read how the Middle Ages, through the construction of that phantasmatic body and the incorporation of Christological thought, arrived at the form expressed in Hobbes's Leviathan. In this register, it is not about One or the Other, about this or that private man, but about the constitution of a community, which sees itself expressed in an artificial body, of which the King is merely the representative bearer. This body is by no means subject to the arbitrariness of some Sun King, but it is strictly structured; it speaks the language of its time, which can be called the Language of Representation.

This language – which can be set quite precisely with the end of the Middle Ages, with the birth of the modern face, our Idol – consequently, experiences a fundamental shock in the image of the decapitated King. Yes, you can read the Progress of Modernity as a progressive shock; even more, you can ask if the revolution has stopped or if we are dealing with the aftermath of this temporal rift.

The King's Eyes are open, and they stare into a world without deed and without perpetrator, into a world in which deeds no longer bear any resemblance to those who commit them. If they want to coin a formula for it, it means nothing other than it's no longer ME who does, but IT.

As exemplary, let’s take the year 1968. When we hear 1968, we remember the slogans of our aging revolutionaries, who, admittedly, don't like to be reminded of them very much – so instead, we’ll considerately praise the revolution of life forms. The moon, the contraceptive pill, the sexual revolution, the anything goes. 1968, above all, means IT happened: with a capitalized (Freudian) ID. Now, it’s interesting that 1968 didn't only happen on the streets – the year 1968 also knows two other revolutions that we only rarely, if ever, relate to each other.

The first silent revolution, whose aftershocks still reach us daily, is linked to Bretton Woods. With the end of Bretton Woods, people broke away from the gold standard – a notion that'd long since ceased to be tenable – and moved on to what's called free-floating as the notion of exchange rates being in fluid relation to each other. Strictly speaking, the moment of liquefaction (which you can also translate as liquidation) is much more far-reaching. If, until then, the assignations of money had been considered the representative of a material value such as gold, then from now on, it's nothing more than a sign that is hoped can be kept in check and controlled by other sign systems. But whatever the path of this new money, it comes down to the dilemma of digital money.

Let's move on to the second silent revolution. This is the definition of Death that was relieved-out in Medicine, stating Death occurs when the brain ceases functioning – that is: Brain Death. The physicians have proceeded like the French revolutionaries: they’ve separated the head and the torso from each other, with the aim of preserving the human body as a store of spare parts for other bodies. You see, headlessness is thus a condition for taking the body into service as a Machine with interchangeable parts.

Perhaps – at least, I hope – the reference to the image of the beheaded King becomes clearer. On a much larger scale, what's decided in the portrait of the headless King is repeated here. The way the body of the King has been carried to the grave is a precise foreshadowing of that revolution which hasn't stopped – and has now seized the masses. If the serial Machine demanded the King's head, it’s now making our heads roll.

You see, I take the burial of the King as symptomatic of a present constitutionality. Because the three revolutions that I've just pulled into relief – the revolution of life forms, the revolution of money, and the revolution of medical cartography – can be understood as bodily re-codings. We have the re-coding of the political body (that is, the revolution of the street), a re-coding of the economic body (that is, money), and a re-coding of the material body (that is, brain death).

What they have in common is liquefaction and detachment from the material body. Bretton Woods is detaching itself from gold; the definition of brain death is detaching itself from the integrity of the body; and the free-floating of the street, which was politicized, shows itself, almost thirty years later, as a softening of life forms – you could say everything has become software: digital. When we’ve digitized a body, we can copy it at will – it is no longer One but a clone, a hybrid, inflationary. – In this sense, the end of representation (which speaks of the One and its double) isn't a slogan but a reality.

Perhaps at this point, it's plausible what the story and the temporal rift of the Guillotine have to do with our present. The headless body of the King, whose head is laid out between his legs as a sign of impotence, his glassy open Eyes staring into nothingness, into a world without perpetrators and victims – all this announces an age where the One and the intact man can no longer be the bearer of our truth. This One, lying in the open coffin (and this is the underlying message of the picture), is no longer able to represent the others.

The Guillotine's blade, which came down in the French Revolution, leads us into that world announced in the image of the twitching monks: into the world of the dividuum, of the serial existence – or, as I would like to call the modern mass being – into that world, where, as you could also say, it’s the telematic world in which we dream ourselves away with a glazed look into spaces that are becoming increasingly problematic in our real world.

It's this end of representation that I had in mind when I spoke at the beginning of stumbling into Modernity – and it's this end that progress has passed over as if it were only a matter of distributing the King's power to the masses. However, this proves to be illusionary, perhaps to the extent that power has passed to the masses – so that we could say, in retrospect, that only being excluded from this illusionary power has guaranteed its continued existence. On the other hand, where you don't need the acclamation of the masses (in Art and Philosophy), it’s there that the thought of representation has long since ended.

I don't want to make it seem like the Guillotine represented something like a historical fall from grace.

It seems to me much more probable – at least this is my hypothesis – that the death of the King is only symptomatic of that other crisis that seized the subject in the middle of the 18th century – that the One who’s been connected to the battery of the mass can only be One-in-the-Other.

Here, in the image of the twitching monks, lies the true beginning of Modernity for me, the real revolution and that temporal rift that has to be lifted into thinking.

However, this image of the twitching monks, which I’ve called the state of One-in-the-Other, signifies a re-coding of our thinking that isn't entirely completed. Take the essential pillar of our legal system: the autonomous subject. This subject is naturally nothing but a little King – who holds sway in a social subsystem. However, this concept of a subject assumes that there is a perpetrator, an originator (and it's no accident that the Artist and the Genius is the secret hero of modernity – although this is precisely what should make us think: for the Artist is a King without a kingdom, and even this is disputed since everyone pretends to be an artist).

So the question is: does the Author still exist? If we look at this century’s great catastrophes, particularly their legal reappraisal, it’s apparent this subject has long since taken leave of world history. Perhaps the great totalitarianism of this century has lived on the phantasm that One may merge in the Other, which is the metaphysical one-and-everlasting body of the people – while in reality, One set out to eliminate the Other from the circle of convulsively twitching monks. Perhaps totalitarianism is nothing more than a gigantic attempt to force a unified image, to erect a massive, larger-than-life ME. Significantly, this unity immediately disappears as soon as the mass’s battery gives up its service. There are mountains of corpses, injustice piled upon injustice, but the perpetrators (who have shrunk to harmless little guys) insist on being victims. I SPEAK isn't their slogan, but IT – and IT may be what it wants it to be: the money, the science of our body or the circumstances, thus the world spirit. Whatever it is: it comes down to the system. This brings me back to the year 1968: to Bretton Woods, the cartography of the body, and that year when IT happened.

The revolution hasn't stopped. And it will not stop as long as we say ID and do not take the trouble to write this ID on our own body, which is the condition for being able to responsibly say I. This capitalized ID means a ratio with no more carrier, a ratio having grown so far over your head that you voluntarily submit to it – only not having to think about its legality. This ID has the structure of the Guillotine – the anonymous, nameless Machine.

Whether it's the market surrendering to money’s turbulence, whether it's the scientific ratio flying blind, so to speak, following what’s feasible, whether it's finally individuals who willingly follow the majority just because it's the majority – all this says that decisions are made without anyone willing to take the place of speech and responsibility. ID – that’s the hope someone else will do it – that it’ll happen to someone else. Of course, this ID is a fiction because ID has never really acted; it was always a human being. And so the formula on the side of the perpetrators is: If I don't do it, someone else will because it will happen one way or the other.

You see, this form of rationality is, in small but also in larger doses, a form of death technology. The feeling I, as the decisive organ, is on the retreat here. More precisely: it decides against itself, against its better judgment – with which the Guillotine has inserted itself into the head. In a certain respect, the King's death is celebrated here in an ‘always anew’ symbolic way that we let the axe of some overpowering instance come down as we give ourselves away in the name of this or that instance.

Against this background, the fascination with which we follow death on television becomes understandable; it becomes understandable why, on the other hand, we need all the talking heads, the familiar commentators and presenters. They, whom we recognize, make us believe that the place of the political isn’t, as we might conjecture, empty; they make us believe all this still has a meaning. And the most potent message perhaps isn't a message anymore, but only the familiar, unchanging face. The hope is that it might be possible to keep the face – its integrity. With these faces, we shield ourselves from our damaged narcissism and our facelessness – we console ourselves that our Eyes also look out this screen, just as the dead King looked out from his tomb.

Now, I don't want to give you a sermon, or if I do, that what I preach isn't a return to the one and intact individual – on the contrary, it’s the acknowledgment of his death. Only this cognition enables us to envisage what has taken its place – the multi, or as I would call it: the dividual. That’s the one who communicates (which is the great imperative of our time: the communication, the communicability).

Now we're in an epoch where the problem of the body (or, as I say, the problem of representation) doesn’t even stop at those great mega-bodies that the 19th century put in the King’s place. Modern nation-states, too, have proven to be highly fragile entities; they’re also affected by money’s flow to such an extent that they have to be liquidated, as in the case of the illiquid Eastern bloc. Softened by that liquid symbolic capital flowing over the globe, the bodily boundaries of the old nation-states, which claim to be autonomous, begin to blur, and it becomes apparent that some countries’ money and maps are not even worth the paper they're printed on. In a sense, this is a late consequence of what was sanctioned at Bretton Woods, namely free floating.

Now, if you take this figuratively and consider what happens to a body left in a liquid for too long – it is clear what happens. It becomes spongy, flocculates, and takes on a mushy consistency until it ceases to be different from its milieu. There are now only trace elements, dissipative structures, and flocculations.

Of course, my point isn't to lament this loss of substance and its dilution. I am convinced this process goes back very far and is identical to Modernity. Instead, my point is that we face that temporal rift as it's resolved in the King's death. This temporal rift becomes plausible in all its contemporary virulence when we ask ourselves that question which the Revolution of 1968 concealed about itself – and that could be intensified as: What is a body in the age of its simulation? What is our corporeal body if it can be cloned, transformed, and assembled at will? What is money if it’s nothing but information? What are the Institutions and Social mediating instances that can vouch for currency? Finally, what are we ourselves when we’re no longer one – but divisible actors changing roles from scene-to-scene? Who is this One who’s no longer One-and-Indivisible but One-in-the-Other? So: who claims the right to be not the same, but another, an ephemeris...

Now, in order to come to a good end, I will not even dare to attempt such an answer. I’ll only be content with pointing out that a large part of the questions we ask ourselves today (about the role of labor, about the nation-state, about transnational entities, about genetics and ethics, and the like) are essentially derivatives of this one question: What is a body in the age of its simulation? – One of the hottest, darkest topics in this field perpetuates the dilemma of the King; it’s the question of the One who's inherited the King’s attributes, the Artist. More precisely, it’s the question of copyright. A topic that takes us not only to the heights of art but into the realms of geneticists who decode the genome of a living being and, invoking copyright, apply for a patent on it – or into the empire of Mr. Gates, who undertakes raiding through the history of images...or into the future of work, which teaches us any work that's digitized, that’s simulated, is already in the Museum of Work. Well, whatever the jurists will decide, they won't be able to content themselves with simply talking their way out of the legal subject – it’s that headless dwarf king squatting there in each of us – and yet is nothing at best but a phantom pain...

No, the question will be: What is a body in the age of its simulation? No more – but also not less – and that's the point. Because, in the future, we’ll have to ask this question in the positivity of its openness – that is, if we expect a future. But to be able to ask this question positively, we must first of all stop acting like the King's children....we have to say: The King is dead – long live the future....

Thank you.

Translation by Hopkins Stanley and Martin Burckhardt

Berlin Radio Play Days was an annual event organized by the ARD to allow its regional radio broadcasters to show the public what their taxes were supporting; part of the event included a meeting of Chief Editors, their assistants, writers, and engineers with various presentations and meetings.

“68. Die Geschichte einer Kulturrevolution, Berlin, 2009.

Lenôtre, G. – Die Guillotine und die Scharfrichter zur Zeit der französischen Revolution, Berlin, 1996.

Die Zeitriß, literally a rupturus rifting, a rip or a crack in time that Martin will trace out as a significant leitmotif in his thinking as a der Knisternden Zeitriß or the crackling rift in time...[Translator’s note]

Ruckzuck, literally in no time at all, in a jiffy, with the connotation of something retreating so fast that it occurs in the blink of an eye [Augenblick] – hence an imperceptible occurrence. [Translator’s note]

This was written when the first digital watches appeared, before the smartphone’s advent. So Martin was thinking of quartz clocks regulated by piezoelectric quartz oscillators – not by the gravity escapement mechanism of the analog clocks. So gravity’s physical weight is being replaced by the immaterial, digital oscillations between 0 and 1, which is a rift between old and new conceptions of keeping time. [Translator’s note]

Lenôtre, G. – The Guillotine and its Servants, trans. Mrs. Rodolph Stawell, London, 1932. [Translator’s note]

Here, in no time at all [Ruckzack], refers to a temporal rift happening so fast that the population doesn’t notice how numb they’ve become to the horror of serialized death which has been normalized as a course on a menu to be consumed as entertainment. This trace will become a significant leitmotif in The Monster and the Telematic Guillotine. [Translator’s note]

Lenôtre, G. – Die Guillotine und die Scharfrichter zur Zeit der französischen Revolution, Berlin, 1996.

Martin is setting what makes the Guillotine so unique as the Machine that has first relieved-out Modernity in this word-play of Das Auge, das Eye, das Ich. Das Auge is about Representation and its Central Perspective as the Sovereign King; Das Eye is Representation’s death by the Guillotine’s cutting it into the projective gaze of the Ich; thus, Truth is now in the Eye of the Beholder and the simulacral headlessness of the res publica. [Translator’s note]

Oratorians are members of the Confederation of St. Philip Neri, which is a group of priests and lay brothers who are bound together by an oath of charity but no vows. [Translator’s note]

The Abbé Carrichon accompanied the widow Noailles and her family to Paris after the revolution. He’d been the confessor of the widow’s daughter-in-law prior to the revolution and became very attached to the family. [Translator’s note]

European Executioners weren’t allowed in the areas they served, except in the performance of their duties as seen in the full title of the role: maître de hautes et basses œuvers [master of high and low works]. High works included the spectacle of capital and non-capital punishment, while the low works were the unsavory but profitable side jobs, including cleaning cesspools and collecting discarded carcasses. The basses œuvres included oversight of other social pariahs, meaning they could levy taxes on gambling houses, prostitutes, and lepers. However, it was the Executioner’s droit de havage [right to dip into] entitling them to predetermined marketplace goods that vendors deposited in their havage bags. [Translator’s note]