In the Working Memory

But let your speech be: Yes, yes; no, no. For whatever is more than these is from the evil one. (Matthew 5:37)

In the early 1980s, Martin Burckhardt, a young, aspiring writer, completed his Master’s thesis on Walter Mehring and Dadaism. After writing his first radio play in which he’d gathered a group of Dadaists in an old folk home and called for the death of modernity, he soon found himself working in the recording studio with Johannes Schmölling, who’d recently departed from Tangerine Dream so he could devote himself to his personal projects. Martin was suddenly surrounded by the futuristic technology of musical equipment of the 1980s, like samplers, sequencers, and rhythm machines that were quickly evolving with the introduction of digital synthesizers. And it was this experience that initially sparked his questioning of precisely what the computer was.

Besides this artistic work on experimental sound pieces, Martin also did a series of one-hour radio features, including reports on Disneyworld, Artificial Intelligence, and Medieval Cathedrals. And during this period, he continued his reading and thinking about computers as he became more convinced this device was having a profound, unknown impact on our cultural psyche — leading him to publish Digitale Metaphysik1 in 1988. In that first essay, he began tracing the major themes about the computer’s potential affectivity on our thinking, language, onto-political-theology, and our understandings of ourselves that he’s continued writing about in his current works.

In 1989, Martin was asked by editor Wolfgang Bauernfeind to join him in working on a 3-weeks seminar at the Berlin Academy of Fine Arts (Hochschule der Künste), where he began working with young actors. During this period, he also began publishing in Leviathan2, where he published Im Schatten der Kathedrale and Der Blick in die Tiefe der Zeit, both of which will be chapters in his 1994 Metamorphosen von Raum und Zeit.3 Martin mentions in Éducation Sentimentale II that the editor asked him to write a text on the rationalization of work, telling him that all the University professors he’d previously asked lacked the courage to do so and had turned him down. The result was in January 1990, coinciding with the birth of his son, that he published Im Arbeitsspeicher — Zur Rationalisierung geistiger Arbeit4 as part of a political textbook on the Social Philosophy of Industry Labour where he explored the effects of digitalisation5 on the intellectual workspace.

As he continued developing the themes from his first essay, Martin sketched out how the rational edifice of production and its metric valuation have changed within the computer’s workspace of temporal rationalizing. He begins by asking the simple question of how classic notions of production have become disconnected from the field of the real in the abstraction process — which he’ll eventually ascribe as Attention Economics6. He points out how, unlike in the physical world, the Arrow of Time has become reversible within the rationality of digital space — meaning it’s the equation’s synchronic predictability of the vacuum floating above the Sea of Air rather than the ephemeral diachrony of our everyday experience. And he points out that thoughts and digital goods now move through digital space at the speed of electricity as the computer is overcoming Space and Time's physical world logistical limitations. These changes reflect the beginning weaving of a red thread through Martin’s labyrinth of thought, tracing the epistemic shift seen with Kant’s recasting of space, movement, and time as the empirical foundations of Modern Science — which, coincidentally, is also the start of the shift from the second Universal Machine to the third, that is, the shift into Modernity under its sign of digitalisation.

In particular, Martin looks at how the Digital Sign’s economic rationalization affects the physical workspace with its separation of hand and head in a humorous play on diaita, how you ingest something that’s no more than a descriptive simulation — and how it can become something having no counterpart in reality, that in a sense reality has been dissolved completely. In this case, the chemical composition, as the genetic code of chicken, Indian, can be digitally manipulated to create a brand new flavor having no bases in reality, say Pork Dog, Chinese. And, despite its humorous illustration of food production reduced to its schematic essence, Im Arbeitsspeicher is a very serious exploration of how fissioning something from its physicality into the computer’s digital temporal-spatiality turns it into a simulacral genotype that can be dissimulated into an infinite number of phenotypic forms, including its annihilation. This was the discovery of a new world outside of our traditional notions of reality where things having no basis in the real world could be created. And more importantly, this new world would profoundly impact the human psyche – something Martin continues exploring in his works.

— Hopkins Stanley

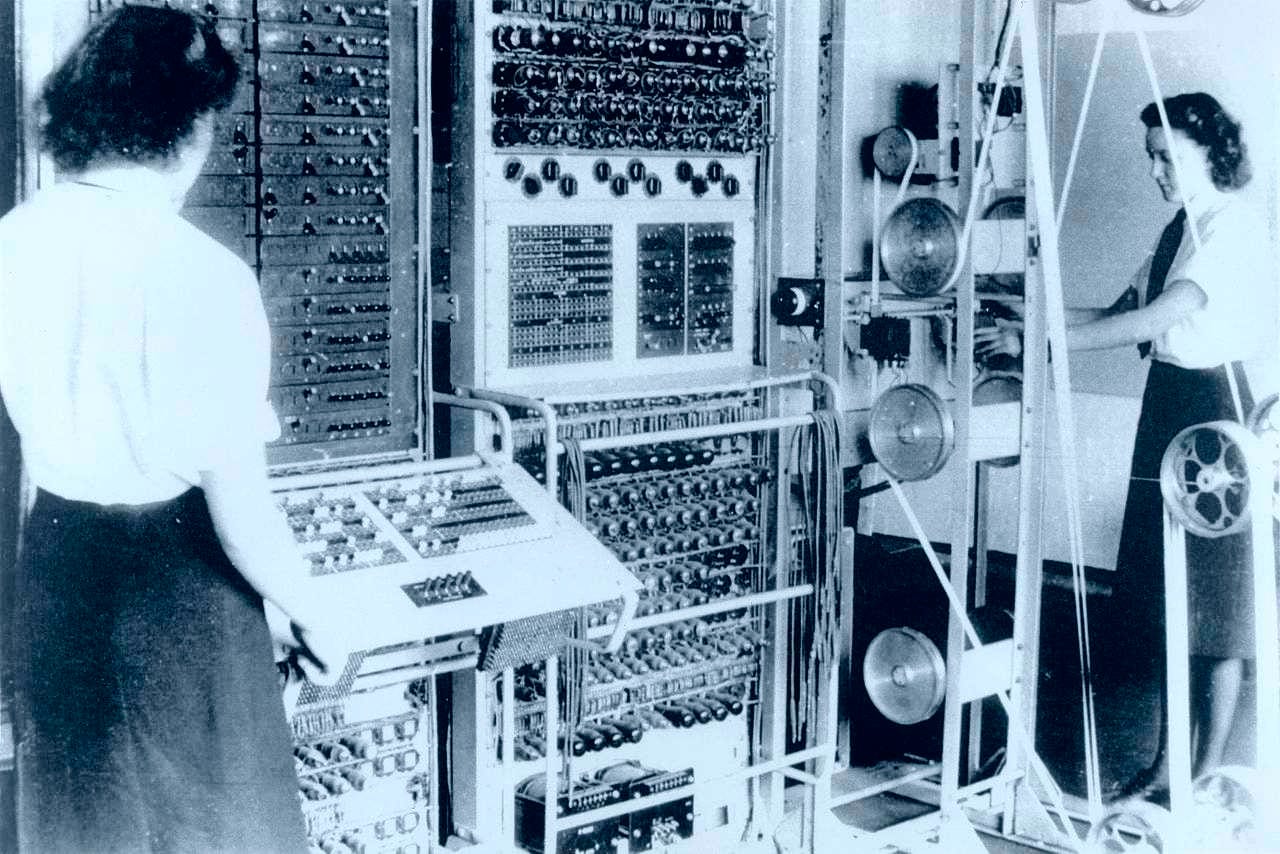

NB — The German title Im Arbeitsspeicher: Zur Rationalisierung geistiger Arbeit reflects a wordplay not obvious in its English translation. Im Arbeitsspeicher [In working memory] refers to a computer’s RAM, while Zur Rationalisierung geistiger Arbeit [On the rationalization of mental work] refers to the human computational labour being obscured by the digital computer; exemplar is remembering Alan Turing’s WWII decoding effort where initially the computer referred to the young women manually doing the tasks of decoding (sometimes referred to as the Big Room Girls). Then, after Turing developed his Colossus apparatus, the machine replaced the human worker and was given the name computer.

In Working Memory: On the Rationalization of Mental Work

But let your speech be: Yes, yes; no, no. For whatever is more than these is from the evil one. (Matthew 5:37)

1: Saying "rationalization" signifies bringing a certain ambiguity into its field of use. An ambiguity that’s unquestionably all too easily ignored in its linguistic uses, not the least from having acquired an overgrowth of appropriative meanings in the various spheres of its application. What is merely a technical improvement for the mechanical engineer becomes something threatening when issued from a company representative's mouth; and finally, while sitting on the psychoanalyst's couch, it becomes a compulsive behavior that devises all sorts of reasons where an abyss, a crackling rift opens up — and wobbling [Taumeln] from a reasonable time’s desire for more rational approaches of reason, it staggers vertiginously from the heights of its abstraction into a bottomless chasm, a little like that cartoon character still moving forward in the air for a while before becoming aware of his circumstances (which then, according to cartoon logic, coincides with their current crash).7

Fundamentally, all reason, disciplined, segmented, and reduced to its partial truths, finds itself in this dilemma.

This embarrassment is generally avoided by concentrating on the abysses of competitive differences, which, as in the comic, has led to those wonderfully well-rehearsed relationships of enmity based on the division of labor, which keeps the momentum of things moving in the first place. At the same time, this competitive behavior also obscures the common ground still existing in the rationalization process, despite all the divergences. It's not a substantive commonality but a structural one. Just as reason isn't exhausted in being a specific reason, the concept of rationalization isn't bound to pre-determined laws — Au contraire, rationalization’s characteristic streamlining process doesn’t tie itself to any particular set of tools; instead, its ratio of logic remains in a receptive, sponge-like state always ready to erase and replace itself with a new, more efficient schematic. If we fail to recognize this Joker function, reducing the process to its historical (which generally signifies its contemporary) manifestation, we would be misjudging its structural law, namely that we are dealing essentially with a dynamic, temporalizing process.8

From this perspective, every ratio tends towards economic rationalization, virtually an immanent compulsion to rationalize.

Max Weber's statement that modernization isn’t a kind of carriage from which you can exit reflects insight into the time orientation of the process — a time orientation that makes returning to a past state impossible. Rationalization signifies: time’s arrow, an irreversible movement, and, being analogous to the Time Arrow of Thermodynamics, we can consider its process as an intellectual form of entropy. This is what's hidden in the wordless shoulder shrug or all those cloudy references to outcomes being determined by higher powers (the wheel of history, the course of things, or the facticity of the factual) — that there is no way back in time, but only forward movement into the future. That a word, once said, a thought, once uttered, is in the world: said is Said. And: Said, Done. In a different way, this is also the authoritative non-binding face of the company spokesman proclaiming: If we don't do it, someone else will.

2: The fact that it is possible to speak of a rationalization of intellectual work at all is already a remarkable historical date since it means that the intellect, which metaphorically seemed to hover above the waters and, de facto, above the lowlands of industrial production, is confronted with the scheme of its replaceability. Pronounced clearly, this is the moment when the machine not only gets on the human body but rises to the mind to replace it. Work that only a few years ago was still surrounded by the aura of intellectuality is beginning to appear replaceable against the backdrop of the Expert System9 with its database and intelligent software, making it palpable that much of what has successfully evaded the process of mechanization so far could also be subjected to the logic of the Machine. During the early period of industrial development, socioeconomic entropy was exclusively restricted to the lowlands of production; however, now it’s spreading to areas once considered irreplaceable because of their greater complexity. This means the very structure of intellectual work is becoming questionable, as there’s no doubt that it ceases being intellectual work when a Machine can be substituted for it. It’s here that the inherent conceptual flaw emerges in its lack of positive formulation.

Intellectual labour has primarily defined itself as being differentiated from the tangible, physical sphere of production but has yet to be given a positive formulation of what constitutes its distinctive characteristics.

This conceptualization distinguishing between mental and physical work is far too narrow, if not just a mental corset used for justifying all kinds of prejudices while not capturing the work’s diversity. To be precise, it is questionable whether this antinomy has ever been suitable to grasp the complexity of intellectual work adequately: there’s undoubtedly even a physical side to work considered quasi, the pinnacle of virtuous social activity. After all, there is no denying that a piano virtuoso performing a Chopin etude or Scriabin piece is engaged in the highest degree of embodied handwork, or more precisely: that playing would be impossible without the interactive working together of hand and head10. Here is where we see the division between head and hand is a misleading, ultimately merely metaphorical one; this division’s deeper reason isn’t found in the antagonism of hand and head but is based more or less on the degree of interchangeability. It is not hand or head that makes the difference, but the question if a work has already been thoroughly rationalized and mechanized and to the extent which it figuratively has become a Machine.11 It isn’t the physical aspect of work that means the worker’s privatization but that the worker has become a part of the machinery on the assembly line. In this sense, the antinomy of hand and head is based on a differential of replaceability (and thus the machine prosthesis). This is what the simple competitive difference between head and hand hides: that work is not only a matter between people, but in its shadow, the Machine also shows itself (as a quasi-objective, de facto, historical reference system, by which the value of a work is measured). In this sense, the turning point that allows us to speak of an intellectual work's rationalization is historical and a novelty: with the computer, a Machine exists for the first time, which no longer gets on the human's body, but rises to his head. Or not?

3: To understand the rationalization potential that can be emanated from the computer, the first question to be answered is what kind of rationality is already hypostasized in the computer. Interestingly, this question, so guilelessly poised in the room, leads to a terrain of disputed faith that isn’t any less inferior to the medieval debates over the angel’s gender in sophistry and scholastic finesse: namely the question of if and to what extent it’s is possible to breathe intelligence into the Machine. Rather than getting involved in the arguments, I find it remarkable how this discussion is permeated by a more chiliastic12 than rational tone. Undoubtedly, it seems easier to conjure up a Ghost in the Machine without hesitation rather than getting involved with a question that first tries discovering what kind of intellect has already been objectified in the computer.

Apparently — and this is probably one of the main reasons that such a debate has been able to break out, especially in such a tone — nobody seems to know quite what the computer is actually used for. This blurring isn't by chance, but the conceptualization of the computer as a tool (a typewriter, calculator, pencil, database) can’t be expressively exhausted in any of its application forms; instead, each is only a possible phenotype, a manifestation beyond its genotypic encoding — after all, ultimately everything can be traced back to its binary coding. It’s this element of coding, the linguistic characteristic that leaves the computer's tool character undefined: an open system, which we might perhaps frame most appropriately as a UNIVERSAL MACHINE13, as a kind of workshop or environment in which all other sorts of machine possibilities might appear. Like money, which can be converted into all conceivable commodities, the computer can be transubstantiated into all conceivable tools, assuming that they submit to its currency, which is the language of the binary code. In a sense, the computer reveals the paradox of an "empty rationality," a mere space of possibility that is neither temporally nor spatially closed — that is, it can also serve as an environment for those programs that have not yet been written, that have not yet been conceived.

Nevertheless, even if the computer's rationality seems empty, it can still be described on another, much more abstract level. The rationality, or: the tool character of the computer, consists in its capability of representing any segment of reality, assuming it survives the analog-digital transformation, meaning: the metamorphosis from material to writing. This may be a tool, a material, or even an entire, highly complex work process - encoded in binary form, de-materialized, and homogenized as information; it becomes accessible to all conceivable symbol operations. This is the decisive characteristic of the logic of analog-digital conversion, the dissolution of a material process into its functional content.

The simplest exemplar is that of a typewriter and its computer image: a word processing system. Effectively, each letter that appears on the screen is no longer the letter itself but the description of a letter, just as the paper is the description of a piece of paper and the typewriter keyboard is the description of a typewriter keyboard. As a mechanical entity, the typewriter has dissolved into its materiality; it is present only as a program, as a series of encoded instructions, no longer material, but WRITTEN14.

This is commonly called a simulation, meaning what appears on the monitor screen doesn't exist in the computer as it’s only the ephemeral appearance of a binary-coded voltage diagram. In reality, binary coding is a kind of semantic nuclear fission that, in the computer, is nothing but an oscillation between zero and one. This is why even a word processor, even when correcting a spelling error, doesn’t understand what it is correcting — it isn’t comparing and replacing words but chained combinations of zeros and ones.

Nevertheless, the term simulation isn’t particularly well chosen as it suggests we’re merely dealing with an artificial, sham reality. While analog-digital conversion means a dispensing with material reality, the transfer into the digital aggregate state doesn’t in any way mean the decoded sign would get forever lost in a black hole — au contraire. Analogue-digital — the codification of the material always also contains, at least as a possibility, digital-analogue — the materialization of the writing.15

4: On pre-packaged frozen meals, you can sometimes read that the dish inside (let's say an entrée: chicken, Indian) is enriched with natural flavorings. Opening such a package, the chicken can be identified without a doubt, both visually and by taste. Quite often, what passes, taste-wise, for the somewhat depraved version of chicken, Indian conceals the result of some quite complex food chemistry work. For example, industrial processing in giant vats means the chicken flavor disappears even in products with high-quality ingredients (like organic chickens). In this case, they resort to adding flavor enhancers or natural flavorings, a euphemistic expression for something not found in nature, not even in the cooking pot, but at most in the laboratories of food chemists. An actual chicken, Indian flavor is broken down into its acid and ester compounds with the help of a computerized spectrogram, which, depending on the matrix (that is, according to the taste of the original chicken serving as a flavor template), shows a characteristic pattern, which is why we might speak of an olfactogram, a taste sensation's fingerprint. This specific taste can now be produced in the food laboratory even without the aid of a chicken — and it could effectively simulate the taste of chicken when added, even if the real chicken has mistakenly not been used in making the pre-packaged entrée.

In this sense, the chicken, Indian is already applied deconstruction, a fissioning of signifier and its signified, or, put quite simply and in all-worldly sweetness, the taste sensation of chicken detaches itself from a materially-existing chicken. Strictly speaking, even if the sense of taste can be deceived, we are dealing with two things: the taste sensation of a chicken, then the chicken itself (which, from the perspective of the somewhat more discriminating gourmand, however, is hardly seen as anything more than mere garnish).

You could consider this little trick of food chemistry legitimate, even desirable, if you’re part of the convenience food-consuming community. Still, it isn’t the end of the story. Deconstructing a taste sensation means that it can be modified at will once encoded into the aggregate state of writing. After all, there is no need to stick to the original chicken once it has been encoded since it is possible to think of any number of derivatives or even crosses with other flavors, unheard-of sensations of taste that have hardly ever been tasted, and why, if there is already a category such as International Specialties, why not also a Pork Dog, Chinese?

Undoubtedly, if we look at the work of the food chemist, especially their position in the production chain, a decisive reevaluation can occur here. Previously, its function was solely supportive, ensuring the preservation of the dish being prepared; now, its position is central, simply because it is here (and not in the cooking pot) that the informational values, which determine which flavor design the product will ultimately receive, are created. The cooking process has, very literally, become an information-processing process — fed with a rationality that will unleash a hitherto unknown level of experimentation16, at least in ready-to-eat cuisine. And it certainly doesn't take much imagination to imagine that the chemist in question, once having developed a taste for it, will acquire a library of all possible taste sensations and that, equipped with such a cookbook of cookbooks, will, in turn, create new combinations: a bit of Bocuse here, a bit of Witzigmann or Haeberlin there; possibly, if she’s still alive, also erecting a ready-made food monument to his mother, housewife-style. Naturally, after completing such a syncretic culinary work of art, it’d be essential to find side dishes that would adulterate this little masterpiece from the food laboratory as little as possible with their own taste. Here, we’d be looking for the most tasteless product possible (in other words: chicken).

5: Any substance (be it a chicken flavor, a sound, or a picture), insofar as it has been digitized as a simulacrum inside a computer, has become a raw commodity consisting of nothing other than writing (an informational raw material of a second nature).17 This passage into a digitalised aggregate state also means, in a certain sense, the privatization of nature where only the operative rules of writing are valid. Where these data are processed, material reality no longer applies, and only the sign operations permitted by the computer's binary code are valid. Ultimately, even an image of nature (the olfactogram of a chicken, Indian, the audiogram of a human voice) is no more than a data pool that can be arbitrarily copied, edited, and subjected to all operations like any conventional series of characters consisting of numbers, letters, or lines. The 1:1 reproduction — in the sense which we assume in our conventional audiovisual reproduction media is only a particular case — the digitalised material allows specific parameters to be isolated and edited; so that derivatives can be formed; and finally that hybrids can be produced, which can be modified as much as desired (as they, although derived from a "natural" sense perception, would otherwise be impossible in our sense world). In a certain sense, any digitally deciphered substance becomes a genus since it contains, like an ancestor, a whole genealogy, the family of its possible expressions.18

Generally speaking, the computer reveals in a new dimensionality that all knowledge is coded, that it is representable and changeable in the system of an operational language. This explains some of the enthusiasm for the new "holistic" figures of thought, the joyous syncretism that has taken hold in all the sciences. But, undoubtedly, computer logic works like the Latin of the Middle Ages as a universal language (which is probably why it will be required for the future class of intellectual workers to master the grammar of this thinking).

If you considered that just a few years ago, the lament was that knowledge was incessantly segmenting itself, fragmenting into ever smaller portions of expertise, into a splintering of splinters, a Babylonian variety of languages; it now seems as if the computer, or actually: the concept of information, has unified thinking into a whole. But, even more astonishing, the fracturing into individual technical languages hasn’t stopped but has continued even further.

The realization of this wholistic coherency, this holism, isn’t based on rediscovering a common language but on how semantics has become irrelevant. This coincides with the discovery of a deeper common structure: that everything is structure, encoded, the phenotypic manifestation of genetically encoded information. In this sense, conceptualizing information as a universal language is a higher-order meta-language; it means a detachment from semantics, substance, and the materiality of the Real.

6: A decisive transition occurring with the computer is represented by thinking — substantively — reaching into a virtual space. This may be a somewhat cloudy statement, but it's quite a tangible reality for an architect using a computer. It signifies nothing more than that his working field has acquired three-dimensionality. The flat surface of the drawing board goes into depth since all construction elements are stored in a three-dimensional coordinate system. The plan literally becomes virtual space. And so, the architect is no longer working on a two-dimensional but a three-dimensional plan, structurally making his work closer to the traditional three-dimensional wooden model (which has crowned every architect's work) than a drawing on a drawing board. Even if the concept of simulation, particularly in the computer monitor image’s suggestive pretense of depth, we are not dealing with a trompe l'oeil effect; but with an encoding of space in which each point has a unique assignment in the X, Y, Z coordinate system. For this reason, this virtual space allows us to represent it from any point of view, to probe deeply into its internal structure; to roam, as it were, like walking through the building’s rooms; taking particularly closer looks at details and enlarge them for closer examination; or comparing details with another wing. Such a building project (let's say: a central bank’s headquarters) would have all of its structural features and fixtures detailed out so that it could be walked through in advance of construction: from the lighting; the acoustic environment; carpeting choices; furniture, pictures; from the towel rack to the climate control system; everything could be accommodated in a model such that if the board of directors disagreed with some detail, say toilet bowel shapes, all building’s toilet bowls could be changed to a different shape or different colors at the touch of a button.

7: The virtual space also means: space of virtuality. Just as the three-dimensional space is only an encoding, an n-dimensional space can also be defined, just as it is free to provide a model of our planetary system with minor gravitational corrections. Digitally decoded, that has always meant: transferred into virtuality.

In this sense, the engineer who sits in front of a monitor and tests a material's crashworthiness (even if it is based on actual experimental data) is not tracking the performance of a real crash, merely its description — and strictly speaking, he is not dealing with the hard worldly realities, but with software, a liquefied world, as it were (which is why it only takes one keystroke to reverse the time direction of the event and run the collision backward).19

Thus, an engineer can operate in the computer with materials that don’t (or do not yet) exist in reality; he can simulate certain qualities, set different parameters (tearability, ductility, etc.) if he wants; he can, for example, ask his computer the question about the ideal material or have it calculate which carbon compound is the most stable. However, the answer (which is the most stable carbon compound that has the appearance of a soccer ball) is no longer the answer to a question posed to nature, but it is one posed to a computer program in which nature (as a structure of forms and formulas) is assumed to be sufficiently digitalised: in short, digital solipsism.20 But, it's precisely this virtuality, the written character of such an experiment, which allows for a deeper penetration into the experimental process, since now, unlike in nature, all parameters can be separated from each other and analyzed separately, which undoubtedly — if the basic assumptions are correct — brings a higher penetration and analysis of the subject with into relief.21

8: Perhaps the most appropriate description of the computer is thinking of it as an imaginary workshop inscribed in writing, in which everything inscribable is available in just such a form, namely as an inscription. These are not only tools (programs) and materials (data), but since everything is now written, complex work processes can also be stored. And these complex written operational processes can work together for more functionality, serving again as tools. These little Smart Machines, which can be constantly refined, fine-tuned, and perfected in the course of work, are beginning to emerge. Unlike how we are used to working with physical instructions, work processes can be stored in a computer as a library of procedural operating manuals that can be queried for specific, relevant processing information without reviewing an entire manual. Thus, for example, there is nothing miraculous about a factory floor in which robots manufacture robots; in fact, it is nothing more than a problem that has already been mastered: a book that stands on a shelf, unread, containing the process already in encoded form. So you could consider such a factory shop — not just metaphorically — but as an actual library, more precisely as a museum of work (in which even the work supervisor overseeing the various operations and processes will no longer have any function other than being a museum attendant).

As work becomes scripted and encoded, there is an unparalleled boost to intellectualization and abstraction. Undoubtedly, the written encoding of work brings an immense gain of possibilities with it. Not only can you eliminate any routine activity (once it has been written into a program), but you can also create small smart machines that can be modularly combined at any time, to form larger machines — and, over time, increasingly more complex activities can be delegated to the computer. So eventually, a highly complex work process, which a few years ago would have required an entire group to perform, can be done by a single person or even without human intervention. Naturally, this enables enormous increases in quality standards (perhaps the most apparent exemplar is the constant price drop of electronic articles with a simultaneous increase in quality). Since every problem, once solved, can also be adapted to a computer, work naturally turns to its intrinsic qualities, to all that lies beyond schematized access and beyond the horizon of what is already decoded and possible - and we might say that future work will be virtually compelled to roam the space of virtuality, that it will be even more intellectually: artistic work. In the virtual space, in the sphere and domain of virtuality, it is only the genuinely artistic virtues (not the synchronic, clockwork-like virtues of exactness, precision, and reliability, which are more easily performed by the computer) that make a halfway, semi-rational orientation possible22. The Beuys23 dictum that everyone is an artist, which seemed so remote and unworldly only a few years ago, is already emerging here as an occupational necessity. It is no coincidence that in the traditionally not necessarily art-friendly milieu, daydreaming virtues are suddenly becoming prerequisites for employment: imagination, creativity, the ability to abstract from material reality — which certainly isn’t attributable to a particular passion for art, instead it’s the realization that these are the suitable virtues for working within the virtual domain, the space of possibilities.

9: Undoubtedly, the advent of the computer represents a profound caesura, a crackling rift that, probably more than any other Machine of the Industrial Age, will fundamentally change work’s conception. It is dramatic because it's happening on such broadly radical revolutionary fronts that any attempt to single out individual phases risks misjudging its overall evolutionary movement. Materials, tools, human labour — there isn’t much that can escape its change.

Perhaps what astonishes the most is that there doesn’t seem to be a dramatic metaphor big enough to capture it: that we are actually dealing with a crackling temporal rifting, or, more precisely: that here, in the History of Work, a new intellectual continent is detaching itself and very gradually drifting away...

Or, put another way: the terminus technicus of working memory, which describes a processor's memory capacity, is to be taken literally. Work in whatever form, whether intellectual or physical, can be stored if it can be done with the assistance of a digitally controlled instrument.

Storing means not only that such a process, once recorded, is reproducible for all time (meaning that the computer functions, quasi, as a TIME and MOTION MEMORY mechanism); but also that once it’s stored, it isn’t available in its original form – instead it is in the aggregate state of encoded inscription and, as such, the written, notated, coded work process is changeable at any time. In this sense, the medium of reproduction and the medium of production become the same.

In contrast to the mechanization process of the last centuries, highly differentiated human activities are also now affected. Exemplar would be the playing of a piano virtuoso on an accurately tuned concert grand piano, stored in the form of a movement study, now, having become inscribed in code, written, can be treated in the same sense as the decoded recipe of chicken, Indian. Certainly, this will not immediately cause the disappearance of the species of the virtuoso pianist into pianist, Virtuality. Still, it seems to me almost inevitable that, so far as anyone can take possession of their performance and — even more — use it as a basis for their improvements of it, their gimmicks and games of amusement, that the piano virtuoso figure will lose its iconic status. Strictly speaking, the writing of work amounts to its becoming generally accessible, a collective possession, as in the case of public libraries. Naturally, this also changes the concept of work itself, which until now — as if it were the most self-evident thing in the world — has been based on the fiction of a strictly delimited individual work performance (whose aesthetic exaggeration is reflected in the shining figure of the virtuoso). Of course, this unique work performance will continue to be verifiable (even more precisely than ever), but the individual's signature will disappear within the product itself. The best exemplars of this are perhaps the massively compiled computer program themselves, on which, like the Medieval Cathedrals, several generations of programmers work and have worked - and where the work of the individual, precisely because it can be edited at any time by a successor, disappears, as it were, into the collective.

10: After all, it seems evident that the question of whether the computer will rationalize away this or that activity is far too short-sighted, just as any rationalization debate which only refers to the endangerment of the existing, but does not take note of the change of the ratio, is understandable, but ultimately misleading. The decisive change isn't just a technical one, available for use at any time; insofar as a particular tool is available, it's already fait accompli, that is: already anchored in the consciousness.24 Here, I think, the computer is virtually an exemplar par excellence since it is, when interrogated about its tool character, not useful for anything in particular but is for everything & everyone, a kind of machine of consciousness — which makes materially tangible what's been taboo so far: that thinking also possesses an essential materiality. But more than that, it seems to me, here it becomes visible that every technical development corresponds to a macro-social development, that the one is an expression of the other — which is why it is not at all surprising that what society perceives in the face of the Machine has long since been anticipated by the arts, indeed is already an integral part of the tradition. In this sense, restricting it to merely technical, social, or economic questions is an obfuscating oversimplification of the rationalization process, which already includes changed thought patterns and figures and is inconceivable without them.

For this reason, without being prophetic, I think it's possible to identify some of the broad outlines of what's to come. Undoubtedly, the computer will bring about a profound reevaluation of work, similar to how work was historically reevaluated when machines were first able to take over more complex work processes. In this sense, what is still called intellectual work today and comprises such diverse activities as a death insurance clerk, a refrigeration and air conditioning engineer, or a psychoanalyst will become clearly differentiated and re-evaluated. And in the future, what can't be replaced by a computer will be considered intellectual work; on the other hand, work still thought intellectual work today will be replaced by computers and expert systems. Undoubtedly, any schematically alphabetical knowledge, a collection of what is known by rote — and thus not actually — known, will be done much better by an equally mindless but infinitely faster mental slave. The more machine-like, systematic an activity, the more it has the character of a thinking machine, and the more likely it will fall victim to technological entropy.

We could say that in the face of the computer, the redundancy and simplicity of specific systems of thought are becoming evident — after all, that an expert system can take over the work of a human being is proof that he was not an expert in the first place. All that a computer can do will fall victim to an inevitable devaluation; intellectual work, on the other hand, will have to be measured by whether and to what extent it exceeds the computer's level of abstraction. Interestingly enough, where the mind is already in quasi-crystallized form, it will probably change the least. A novelist writing a novel will appreciate the facilitation of a word processor; nevertheless, the story will not look much different in its decisive features, just as little as a philosopher will begin to think differently in the face of the computer - but frankly, I am not sure...

It is the mind that intellectual work will rack its brains over.

Translation: Hopkins Stanley and Martin Burckhardt

Burckhardt, M. Digitale Metaphysik. Merkur, No. 431, April, 1988. [Translator’s note]

Leviathan — Berlin Journal of Social Sciences is a German Journal published by the Freie Universität Berlin, Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, and Hertie School of Governance. [Translator’s note]

Burckhardt, M. Metamorphosen vom Raum und Zeit: Eine Geschichte der Wahrnehmung, Campus/Verlag, Frankfurt/M, 1994. [Translator’s note]

Burckhardt, M. Im Arbeitsspeicher – Zur Rationalisierung geistiger Arbeit. In: König, H., von Greiff, B., Schauer, H. (eds) Sozialphilosophie der industriellen Arbeit. LEVIATHAN Zeitschrift für Sozialwissenschaft, vol 11. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden, January 1990. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-663-01683-0_15 [Translator’s note]

The difference between Digitize [Digitise in the UK] and Digitalise is one of scale. Generally, Digitize refers to converting a single file or document in a digital format, while Digitalise refers to the conversion of more than a single item, such as a library, community, industry, administrative entity, or an activity. [Translator’s note]

Burckhardt, M. Vom Missbrachswert [The Values of Abuse], Ex Nihilo, May 3, 2023. [Translator’s note]

Taumeln captures this notion of teetering, reeling and whirling as you lurch to and fro in a wobble, struggling to stand upright as you begin staggering and floundering until finally tumble down into what Martin, in dark humor, sees as the image of Wiley Coyote’s invariable sudden awareness of having again fallen for the Road Runner’s trick. It is also a continuation of a thread that began in Digital Metaphysics, eventually becoming der Schwindel [Vertigo] of Post-Modernism in Chapter 2 of the Philosophy of the Machine. See Burckhardt, M. Philosophie der Maschine, Berlin, 2018. [Translator’s note]

This reference to a Joker function is an further observation about the simulacral process of dissimulation which Martin describes in Digital Metaphysics. It presages what he’ll later describe as the Joke Economy in his 1999 lecture on Time as Money as Time that is traced on through his œuvre to be more fully relieved-out as Schein Production in the Psychology of the Machine series. See Burckhardt, M., Vom Missbrachswert [The Values of Abuse], (ibid) [Translator’s note]

The prototype here is the Eliza system developed by Joseph Weizenbaum between 1964-66, with its LISP-like structure. After the AI (Artificial Intelligence) Winter of the 70s, when project funding was difficult to obtain, AI research funding was revived by the commercial success of Expert Systems as stand-alone AI systems, notably in medicine and with LISP programming language. It’s these early forms of AI that Martin is referring to here. [Translator’s note]

In using the phrase hand and head, Martin refers to the Marxian sociological economist and philosopher Alfred Sohn-Rethel's notion of real abstraction and how science conceals the problematic social problem of exchange abstraction that rationalization conceals. See Sohn-Rethel, A. Intellectual and Manual Labour: A Critique of Epistemology, trans. Martin Sohn-Rethel, Atlantic Highlands, 1978. [Translator’s Note]

Here is one of the earliest red thread beginnings of what Martin refers to die Maschine as the ratio of logos becoming transformed into the rational edifice of the equation’s synchronic equal sign, which he’ll ultimately see as the unconscious outsourcing to the Psychotope. [Translator’s note]

This mention of Millennialism is the beginning of another red thread that Martin traces and weaves through his œuvre in various forms. In particular, he will first start by bringing it into relief as Transhumanism in Universale Machine. See Burckhardt, M. - Die Universale Maschine – Merkur, 12/1990. [Translator’s note]

Martin published an essay on die Universale Maschine less than a year after this chapter was published, ibid. [Translator’s note]

Martin’s emphasis on WRITTEN [SCHRIEB] is essential to note as a continuation of what he began tracing in Digital Metaphysics as reminding us that writing in alphabetic script is a universally-symbolic encodement (or economic rationalization) which he will eventually bring into relief as the Greek Alphabetic Wheelwork [Rädarwerk], sometimes referred to as the Printwheel [Typenrad], that is a Universal Machine’s space of empty symbolic signs which can be encoded in it’s outsourced Psychotopic unconscious. [Translator’s note]

This paragraph is an important beginning tracing of a red thread leitmotif in Martin’s thought labyrinth as it progresses through his major works on the Universal Machine and into the Psychology of the Machine series. The dialectic that began in Digitale Metaphyik is continued here; and will go on to become the lost wax process where the forma formata always leaves its imprint on the forma formens — meaning that the fusioning of fissioned encoding back into the field of the real bears the marks of what formed it; ultimately he’ll trace it out as the diabolon/symbolon. [Translator’s note]

This notion of the information processing process — fed with rationality is the beginning of another red thread that Martin will continue tracing out across his œuvre as diaita, the Greek word meaning way of life and the root of the word diet; specifically, how do you digest something that’s nothing more than simulacral information of various phenotypes. [Translator’s note]

Of note here is this notion of a second raw material will that will be traced through to the logos spermatikos, the secondary re-birthing of a god that Martin continues developing in Die Universale Maschine and on through both Philosophy of the Machine and Psychology of the Machine as magmafication. See Burckhardt, M. Philosophie der Maschine, Berlin, 2018, Über dem Luftmeer: Vom Unbehagen in der Moderne, Berlin, 2023, and the rest of the forthcoming Psychology of the Machine series to be published.

In this paragraph, we find a further tracing of the genotype/phenotype red thread from Digital Metaphysics that will become the Phantasms, Chimera, and Windei [non-viable foetus] Ex creatio Nihilo capabilities of the Kraftwerk [our human powerhouse of imagination] arising from the Gesellschaftstriebwerk [Social Drives] we find in Martin’s later thinking. [Translator’s note]

This reflects what Martin points out by quoting Max Weber in aphorism #2. Analogously, Weber also points out that science is a demagicification which we call the natural sciences; something Martin continues developing as a leitmotif that blossoms beautifully in Philosophy of the Machine, coming into full-relief in his conversations on Ex nihilo and the Psychology of the Machine series, (ibid). [Translator’s note]

This reflects Heidegger’s statement that science has its own method. Here Martin points out computer simulations don’t reflect the real world and its conditions; instead, they represent a particular moment that’s been sampled, digitally encoded, and manipulated — meaning the computer’s digital solipsism is analogous to Boyle’s Vacuum Chamber.

Structurally this reversal of time’s arrow is a thetical vivisection of symbolic logic — digitalisation is a symbolic death. Across his œuvre, Martin traces this out in greater detail as the coining of coinage and in the etymology of Leichnam [Cadaver or Corpse] in his consideration of the too-perfect Machine of death — the Guillotine and how it’s relieved-out in the French Revolution’s Psychotope. [Translator’s note]

This is basically the question of surplus value. - And surplus value means thinking something the machine cannot yet do. We end up, as in the process of the lost form, with the imagination. The question is: If thousands and thousands of forms are possible, why does this particular form convince us of its authenticity - and not that one? [Translator’s note]

Joseph Beuys (1921-1986) was a German artist and cultural theorist who invented the term social sculpture, which Martin will use as a strand in developing his thinking about Gesellschaftstriebwerk of our Universal Machines and their Psychology. [Translator’s note]

This tracing of Logic’s ratio into the edifice of economic rationalization is the red thread that is relieved-out in Martin’s thinking labyrinth as the psychotope, the Machine’s unconscious staging of our shared conscious field of the real and its psychology. [Translator’s note]