There are lines of relationship that seem bizarre, especially when they are found in one and the same person. Without a doubt, Carl Schmitt belongs in such a register, and this is even though he personally did not undergo any significant shedding of his skin, but remained largely true to himself in his philosophy, from Political Theology to his late writings. More than the thinker, therefore, his followers leave behind the impression of a hopelessly fragmented, indeed downright multiple, intellectual bunch. That Carl Schmitt (who, in the Weimar Republic, was still courted by the Communists and revered by Walter Benjamin) should become the intellectual stirrup holder of the National Socialists is a turn of events that could be explained by the horseshoe theory, according to which the political extremes touch each other. But it is, however, much stranger that the crown jurist of the Third Reich, with his writing on the partisan, should become the spokesman for the Red Army Faction. After all, their impulse was precisely settling accounts with their parent's generation and the National Socialist legacy – which should have prohibited Schmitt's invocation. That he was nevertheless rediscovered had to do with the shared contempt for liberal democracy (which Schmitt derided as a wishy-washy State) – and the fact that preaching a redemptive state of emergency certainly suited the terrorists' logic of escalation. However, this is not the end of the story – and it is the subject of this short text. Because just when Francis Fukuyama was proclaiming the end of history, a decidedly postmodern mind like Jacques Derrida fell under the spell of Schmittian thought. Derrida's fascination is explained by the fact that he (as a philosopher who teaches the language construction of reality) gravitated toward Schmitt's decisionism. For:

Sovereign is who decides on the state of exception. (Political Theology, 1922)

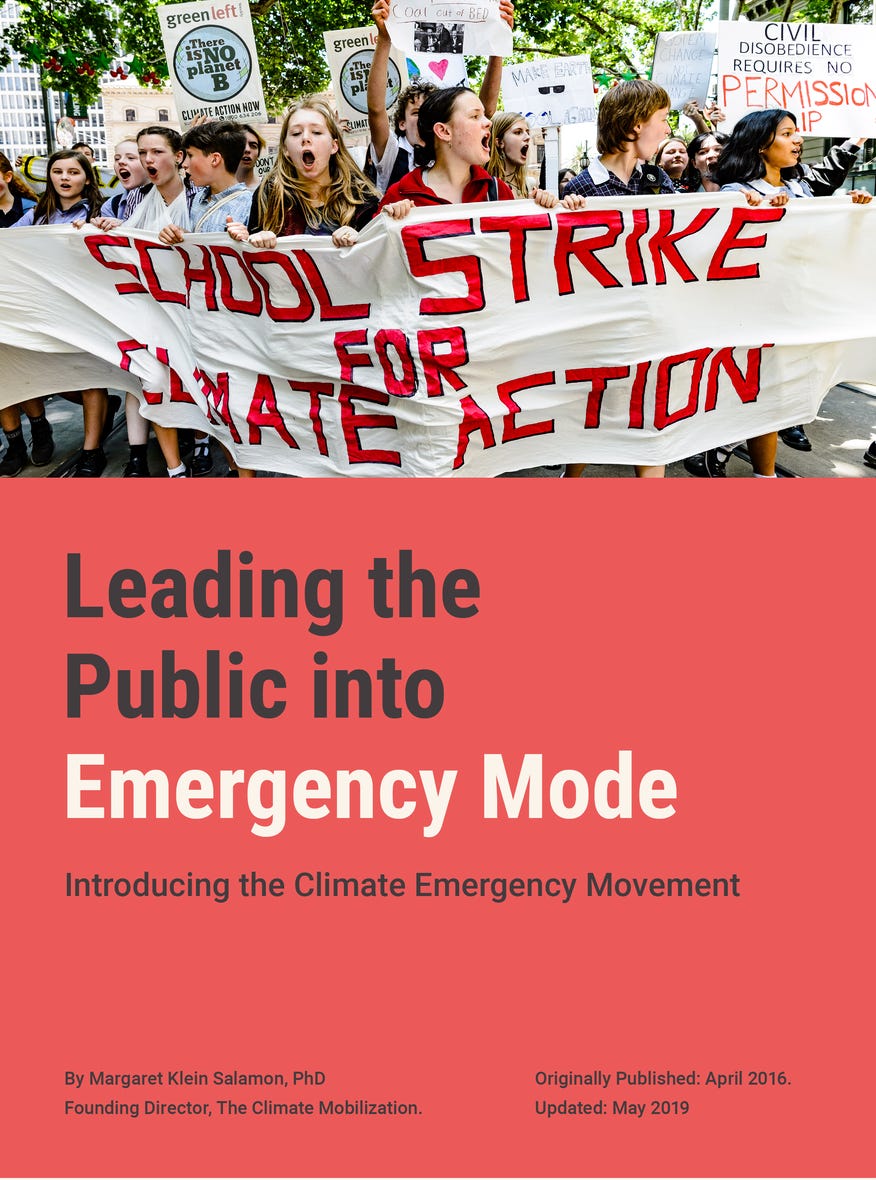

And because this flatters the philosopher's vanity, it is no mistake to understand Derrida's praise of Schmitt as "the last great representative of the European metaphysics of politics" as a form of self-praise. But the references to Carl Schmitt becomes more bizarre when one sees how a thinker like Bruno Latour, who is equally unsuspicious of postmodernism and right-wing machinations, revives Schmitt's political theology in his Gifford Lectures. In doing so, Latour uses Schmitt's notorious friend-and-foe distinction to create an entirely new kind of schism, one that can no longer be reconciled with the classic distinctions between left or right, progressives or conservatives. For now, the earthbound (the Gaia worshippers) are played off against the world-less Anywheres. In a curious way, political sovereignty – the Mortal God of Thomas Hobbes – is thus naturalized. And thus Gaia (as the State of Nature, which Latour writes with a capital S) takes the place of the worldly Leviathan.1 With this return of the political order to a state of nature, Latour proves to be the spokesman for the contemporary environmental movement. In any case, it is not surprising that this argumentation has been adopted by climate activists – thus popularizing Schmittian thinking, indeed making it an Apocrypha of pop culture. A fascinating document in this context is by American psychologist and climate activist Margaret Klein Salamon. In 2017, she published Leading the Public into Emergency Mode, a strategy paper that is being taken to heart by groups such as Extinction Rebellion and the Last Generation we will turn to next.

However first, the question arises: what is so appealing about about Carl Schmitt that a wide variety of movements have succumbed to his thinking? The above list makes it clear that no particular worldview can be identified but that Schmitt's thinking, depending on the case, suits different doctrines and mentalities. In addition to the radicalism and verbal clout of the self-proclaimed Conceptual Ballistician, his teaching of sovereignty proves to be the connecting link – a logic of self-empowerment through which communism, national socialism, counterculture, and environmental activism stake their claim to power. When power becomes a question of decision as a power word, even the defeated can speak it – the only desideratum is their will to power is so pronounced that they can proclaim a State of Emergency. Once this power word has been spoken, the situation is clear: friend and foe are separated, the agenda is set. Of course, the question arises as to who authorizes the person in question to make this schism. Here it must be remembered that Schmittian decisionism, articulated as a critique of sapless and powerless liberalism, is inseparable from the divine, a political theology. Now the source of this doctrine is by no means to be attributed to a particular faith; on the contrary. What prompts it is that liberal democracy is based on a highly fragile faith in reason. And really, Schmitt succeeds in unhinging the liberal conception of the state with a single sentence: All the concise concepts of modern state theory are secularized theological concepts.2 And because this reminder of the modern state's religious origins is absolutely precise, this sentence brings the unconscious of liberalism to light. This, however, is not much more than a genteel illusion, a pseudo-rationalism that doesn't want to perceive the condition of its possibility. If the dictum of Schmitt's student Ernst-Wolfgang Bockenförde enjoys increasing popularity ("The liberal, secularized state lives on preconditions that it cannot itself guarantee"), this is saying nothing other than that the liberal state springs from a religious environment, indeed that secularization is not a disenchantment but only a rededication – towards a political theology. For this reason, Schmitt immediately follows the reminder of his historical genealogy with a parallel statement: "The state of exception has an analogous significance for jurisprudence as the miracle has for theology."3 Here though, a question arises which is not answered by Schmitt, namely: How could faith translate itself into a worldly order of reason? A wonderful exemplar is how the emergence of the European treasury, as a new order of reason, is established using the imitato Christi. The Scholastics, the Spin Doctors of the Middle Ages, had a great interest in elevating the Roman emperor's purse (the treasury) to a quasi-divine authority. If the good Lord, they argued, can be omnipresent and omnipresent everywhere, then this quality must also be inherent in his representative on earth. With this equation, the precedent of the immortality and omnipresence of the treasury is established. Even more: with this dictum, the prototype of the legal entity is created, which, as we know, possesses immortality (for at least as long as it doesn’t go bankrupt). If one follows the history of Leviathan, such translations abound, and Schmitt's diagnosis certainly corresponds to historical change in the development of the European state structure.

However, Schmitt does not say a single word about how this transformation took place and what the reasons for this transformation are. And with good reason. If he had become involved in this prehistory, he would have had to deal with the questions of the concrete state machine: Economy and technology. This would have dissolved the point of political theology into hot air – it would have been impossible for him to endow power with that divine aura. Instead of coming up with a triumphalist gesture, that is, to come up with authority over the state of exception, on the contrary, would have been doomed to demonstrate the impotence and impotence of political theology. European institutions are by no means triumphalist spiritual foundations but can be understood as compromise structures – like the State's monopoly on the use of force, which could only become a reality after endless disputes and civil wars. If Carl Schmitt leaves the complexity, which goes along with the economic way and the technology, hidden beneath the table, only the political theology remains. Everything is political – and consequently a matter of decision (as if one could decide from now on not to use watches or computers). If he accuses liberalism of unconsciously ignoring religion, he doesn't act any differently – it's just that his solution consists of asserting the primacy of the political: Said! Done!

This finding precisely captures the fascination of this teaching. Ultimately, it is about a form of self-empowerment – and this, in turn, goes hand in hand with a denial of realities. From this point of view, Derrida's compliment would have to be shifted to a psychological level. What he calls the 'metaphysics of politics' is just another word for narcissistic self-empowerment: a politics of heavenly conquests, with which you give yourself, as the case may be, a supernatural veneer or a divine mandate. In this way, you have climbed to a height from which, enthroned, you no longer have to deal with the travails of the plain (loosely based on the Hegelian insight: "If the facts do not agree with the theory – so much the worse for the facts!"). Because you have been ordained by a higher power and destined for higher things, the world is wonderfully ordered. Not only are the circumstances clarified, friend and foe separated from one another, but also, filled with the importance of the mission, you are freed from having to deal with your own powerlessness and helplessness. All the self-doubt arising from the confusion of modernity is forgotten. If you can revel in the feeling of power, it is because, in contrast to the enemy, you have a deeper insight into the circumstances. From this point of view, the Manichean schism is virtually a psychological prerequisite – which Schmitt has clothed in the quotation adopted from Theodor Däubler:

The enemy is our own question in form.

One clings to the enemy because his blindness is the prerequisite for the ability to be considered king, at least as a one-eyed man. This relationship of dependence is striking evidence that the claim to sovereignty is a borrowed one, indeed that something is being kept alive here that has long since ceased to exist. Transplanting Schmitt's doctrine back into its context, one is particularly confronted with the experience of deep powerlessness. Here is a country convinced that it could conquer the world but then lost a world war and fell into a deep crisis of values and identity. Historically, the battery from which Schmitt's claim to power is fed is purely the opposite. His diaries show a small man struggling largely raging with anti-Semitism and alcohol addiction, a kind of worldly disgust in which everything that is not one's own coalesces into a toxic brew: "Disgust at being poisoned by Jews. Neither beer nor wine in the evening. Thank God, incomprehensible this compulsion to alcohol".

Quite obviously, the sovereignty Schmitt promises is proof of its opposite: Evidence of a deeply rooted sense of powerlessness. Schmitt's artifice – his genius, if you will – now consists in letting this sense of powerlessness sink into a darkness, while on the other side, as if by itself, an aureole of power shines. That Schmitt's teaching has experienced such an intense resonance is indebted solely to this logic of self-empowerment. In the fusion with the movement, the atomized individual experiences meaning and belonging. This is precisely the essence of all identity politics: Empowerment! As a contemporary exemplar, consider the aforementioned treatise by climate activist Margaret Klein Salamon: Leading the Public into Emergency Mode.

Although there isn't a single direct reference to Schmitt, the arguments read like a popularized 1:1 translation: a kind of Schmitt-for-the-masses. The objection she raises against the social majority is that it indulges in an illusion of normality – the belief that one can carry on as before. On the other hand, the author, as a psychologist, diagnoses a widespread feeling of helplessness. What is striking about this argumentation is that the perspective of the autonomous, or at least the self-responsible individual, is abandoned – and, instead, appears in a state of herd behavior. But this is to be taken advantage of. Because the disaster mode also evokes a kind of herd behavior, it is necessary to create a Pearl Harbor moment – and to convey to society the same sense of community manufactured when it entered the war. Attempting to follow the author's argumentation with benevolence is to say that the American war economy, namely the invariably cited Manhattan Project – if you take it in view of pure efficiency – represents an unprecedented collective effort. Now, the dilemma of the current climate crisis is that the catastrophe (that is, the state of emergency unquestionably assumed by the author) is by no means self-evident. On the contrary, indolent ignorance is spreading because the public is not grasping the signs of the times. This must be confronted. What Klein Salamon preaches is, in short, alarmism and mass psychology – techniques that (as she never tires of claiming) all successful social movements have used.

The climate movement must fully adopt the language of immediate crisis and existential danger. We must talk about climate change as threatening to cause the collapse of civilization, killing billions of people, and causing the extinction of millions of species. These horrific outcomes await us during this century, possibly even in the first half of it if things truly slip out of control. This is not a matter of “protecting the planet for future generations” but protecting our own lives and those of the people we care about. We are in danger now and in coming years and decades. The climate crisis is, far and away, our top national security threat, top public health threat, and top threat to the global economy.

While this assessment may seem like common sense even to educated, thoughtful contemporaries by now, the way that Klein Salamon builds up the state of emergency into a psychological ideal state is astonishing. This is because it is related to the psychological flow state, which the Hungarian psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi described as an 'optimal state of consciousness,' a state "in which we feel our best and perform our best." In the spirit of Steven Kotler, who based this insight on the manifesto of the postmodern self-optimizer, The Rise of Superhuman, Klein Salamon portrays life in a state of emergency as the foundational meaning of paradise, a sense of belonging, and social efficiency – only that you have to wake up and enter a state of spiritual warfare (the WWII state) to do so.

This psychologizing argumentation is remarkable for several reasons. That the modern project of the enlightened individual can be sacrificed to mass psychology, indeed that the state of emergency can be welcomed as a form of creating society and meaning, is remarkable in itself – after all, it testifies to the fact that this form of mobilization has the primary purpose of turning an internal emergency into an external one, of imbuing a 'thinly populated interior' as Christopher Lasch has called this mental state, with a sense of meaning and belonging. In this sense, the object of desire (the climate) proves to be primarily a wish-fulfillment Machine4 – showing that what is at stake here is a form of Schmittian self-empowerment. If the world is to wake up, it is because this battle cry puts the individual into a state of self-assurance. Consequently, the psychologist cites the mental flow state that primarily characterizes high-speed athletes as fully merged with their activity. But this is precisely what individuals who need social excitement lack. It is not without consequence that Klein Salamon doesn't at least deal with concrete environmental issues but devotes her entire approach to the question of how to use the logic of virality as a weapon to mobilize the movement. Just as Carl Schmitt could only construct his political theology by missing the point, here we are dealing with a revenant of his thinking – only that the Leviathan has been replaced by an apocalyptic State of Nature, by the raped Gaia.

But this rounds out the picture. The fact that Margaret Klein Salamon's Climate Emergeny Fund supports groups such as Last Generation – and, after the disruption of road traffic, they have taken to attacking works of art such as Monet's Haystacks (after da Vinci's Mona Lisa, Vincent van Gogh's Sunflowers, or the Sistine Madonna) – shows that the real meaning of this iconoclasm lies in self-empowerment – in rising above a past that has been declared fossil. That it is hoped these particular attacks on works of art will mobilize sympathizers is only, to a certain extent, due to the attention economy that makes such actions in social media go viral.

Beyond the collective ecstasy, these actions point to the spiritual void: we are dealing with the exorcism of that inner voice that makes doubt loud. Because if you ask to whom the innovations of modernity are owed, you are not dealing with collectives. It is the individuals in the blind spot of the present that have sought and brought such innovations about — and who, above all, have paid the price for this deviation. And just as Carl Schmitt's failed literary career was succeeded by his state of emergency, the declaration of a climate emergency also follows a totalitarian screenplay; as always, when it comes to the big picture, it is not the world that is at stake, but heaven. The fact that it had to be apocalyptically darkened for this purpose isn't relevant. What does Greta say? I am as happy as I have ever been.5

Translation: Hopkins Stanley, in cooperation with Martin Burckhardt

Bruno Latour: Facing Gaia. Sex Lectures on the Political Theology of Nature. Edinburgh 2013.

Carl Schmitt: Politische Theologie. Berlin 1934, 2nd edition, p. 49.

Ibid, p. 49.

But what's really fascinating is her explanation of why bigger decisions are easier in the first place: "But the exciting thing is: the bigger the decisions, the easier it is. What gives me more trouble are the small decisions. For example, what socks to wear in the morning."