And if you look into an abyss for a long time, the abyss also looks into you. (Nietzsche)

That abstinence is preached, or even that this sermon of repentance falls on receptive ears in the wake of the energy crisis, is hardly surprising. For there is no doubt that late Capitalism is stuck in a productivity trap of its own making – an insight already noted by John Kenneth Galbraith in his (more than half a century old) Abundance Economy.1 Consequently, the void that advertising has torn open with its psychological sophistication is filled with consumer goods that are less than satisfying in the long run. Or, as the apocryphal elaboration of a Fight Club quote goes:

With the money we don’t have, we buy things we don’t need to impress people we don’t like.

Economists may celebrate this as increasing the gross national product, but the futility of such a sham production is apparent to any reasonably bright contemporary. While the criticism may be self-evident, the solution to this systemic dilemma leads to all sorts of embarrassing quandaries of thought. It may be for this reason – because it creates clear conditions – that the Degrowth movement enjoys a particular popularity. The answer to the Post-Growth economy (as it presents itself to the academic audience) consists of shrinking – and remembering the consumptive desires that find only ersatz satisfaction in the form of compulsive buying and conspicuous consumption. And because you want to remember real life in the counterfeit one, the criticism of consumption is immediately turned into criticism of the system. The fact that we live beyond our means and need a second or third earth in the long term to satisfy senseless consumption is the strongest argument of the Post-Growth economy: There is no Planet B. And because the reality principle can be claimed with this lack of alternatives2, any objections to it can be nipped in the bud. But as justified as the critiques of Capitalism and consumption are, the intellectual apriori underlying the Post-Growth economy are questionable, not to mention the political consequences of managing scarcity.

The essential argument that’s been haunting the public sphere since the late 1960s (since Paul Ehrlich’s Population Bomb3and Meadows’s The Limits to Growth4) concerns the finite nature of our planet, which sets limits to the (tendentially infinite) Capitalist promise of growth. Consequently, the representatives of the Post-Growth economy never tire of pointing out Capitalism’s hidden costs (the pollution of the water, the air, the karstification of the soil, etc.). Thus, we are dealing with a systemic conflict, an economic system that not only ignores what it lives on but, in the long run, annihilates it. As economic thinking is translated into a global resource economy, it follows a perspective that sees the economy as a zero-sum game. Against this background, progress is only a kind of shape-shifting; every gain in productivity is a synonym for accelerated entropy. The consequence: a cultural pessimism, which is soon joined by a darkening view of man (which is why the terribles simplificateurs, like Eckhart von Hirschhausen, branded the logic of growth as a cancer5). In the zero-sum economy, the gain of one can only be another’s loss; it goes without saying that the achievements of industrialized Modernity are owed only to a logic of exploitation (first of the third world, then of nature). Based on this assumption, the conclusion is it’s necessary to replace the Capitalistic economy with a Subsistence economy that’s as caring as possible; preserves resources and the environment; and it’s essential to create empowered authorities that ensure the equitable distribution of scarcity (an idea that’s evolved into climate justice in the context of climate change). The decisive counter-argument is that this approach, which only sees a thermodynamic change of form in every progress, misjudges the modern paradigm and the essence of thermodynamics in general – namely, that here we are not dealing so much with the discovery of fossil fuels as with the cunning of matter.6 It is no coincidence this story doesn’t begin with an energy source but with the discovery of an actual vacuum7. It led Robert Boyle, the sceptical chymist, in the middle of the 17th century to a new way of looking at the material world – and this, in turn, led to modern chemistry and the discovery of the steam engine and electricity.

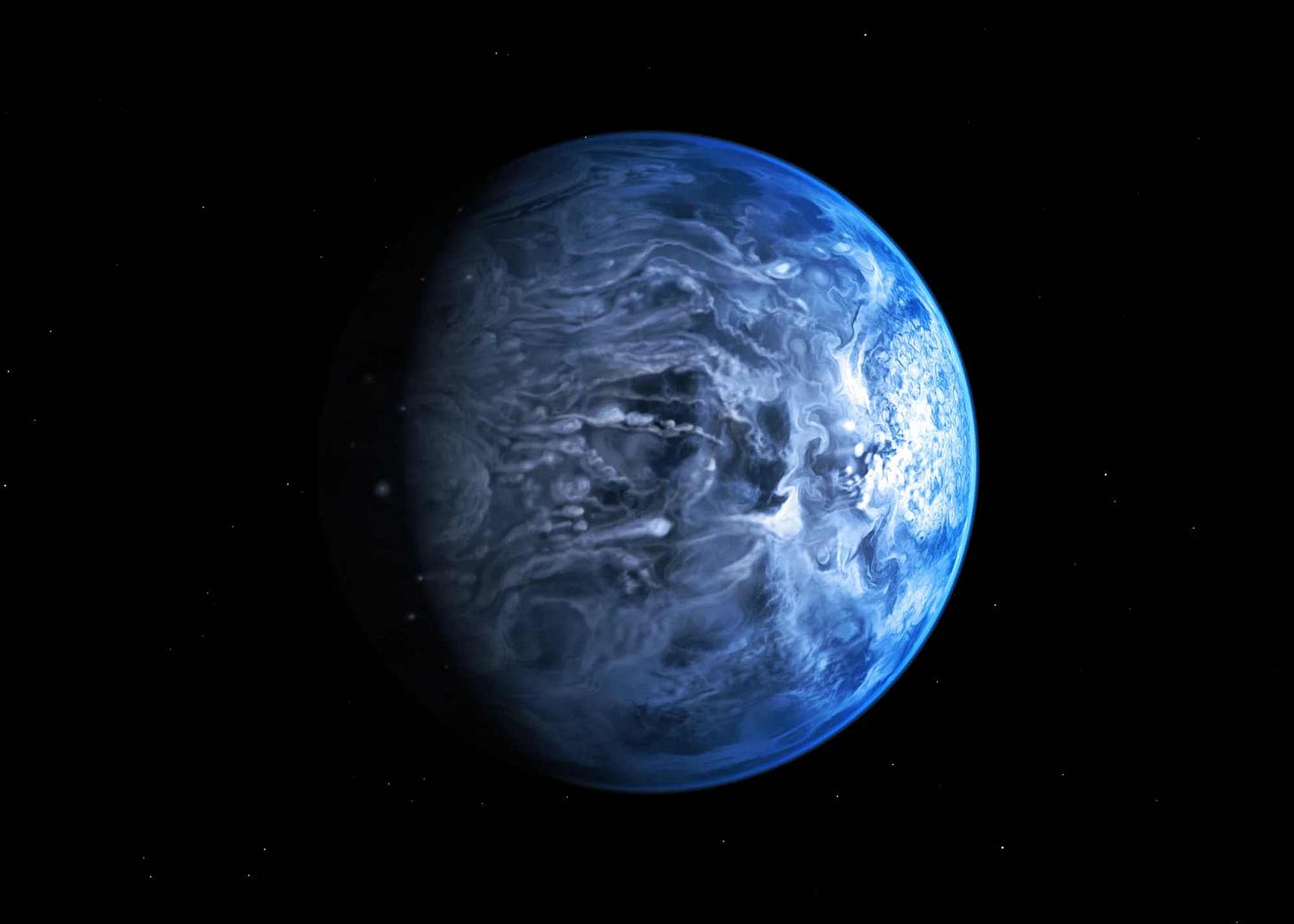

If you try to get a fix on the scientific revolution’s point of view, it is remarkable you have to locate it extraterrestrially, so to speak. At least, this was the insight of Galileo’s successor Evangelista Torricelli, who discovered the barometer’s air column on a mountain was much less observable – from which he concluded that a) air itself must have weight, b) there must be a space above the sea of air.8 Conceptually, this insight anticipates the satellite’s view, which the general public first became aware of with the photographs of the blue planet. In this sense, modern thermodynamics is a product from this height of abstraction, which anticipates the extraterrestrial view (in intellectual form, anyway). But more importantly, is that the progression of thought is being inverted. Here, progress is no longer articulated as transgressing the spatial horizon as a form of the Plus Ultra9, which characterized the early modern era’s dissolution of boundaries movement, but as a Plus Intra, as a walk into the inner world – or as Novalis made wonderfully clear:

Inward goes the mysterious way.

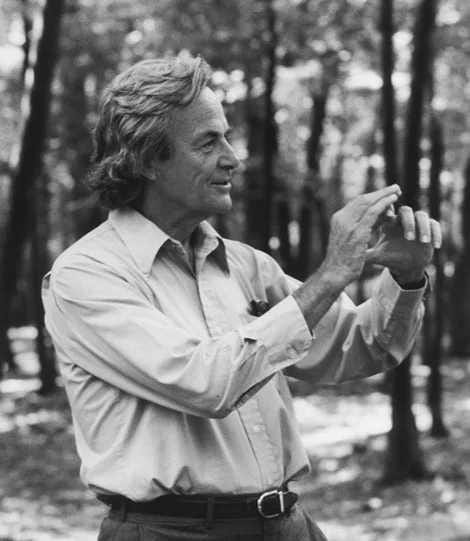

What may warm the heart of the romantic means nothing other than that material land-grabbing gives way to scientific land-grabbing. From now on, growth means increasing intelligence. In this sense, the dominion of space is replaced by science (or how the computer pioneer Vannevar Bush put it: Science. The Endless Frontier). This change of perspective is even more precisely illustrated in Richard Feynman’s beautiful slogan, with which, in the 1950s, he postulated the entry into nanotechnology10:

There’s plenty of room at the bottom.

Every computer chip makes it clear this reversal in the progression of thinking is not a lofty desire but a fact. While the first integrated circuits of the 1950s combined less than a dozen circuits on one silicon crystal, this amount increased by a factor of billions within half a century. This improvement wasn’t from using more materials but from increasing intelligence. In short: What the propagandists of Degrowth are postulating has already long been fait accompli with the Plus Intra of Modernity – the efficiency of a given mass can be improved by increasing our intelligence. If one looks at Modernity from this point of view, it becomes clear that when read as an unleashed battleground of materiality, it can only amount to a misunderstanding. Even the steam engine's history cannot be deciphered unless you understand its initial idea wasn’t the combustion of fossil fuels but the discovery of a vacuum. That this perpetuation of misunderstanding continues to this day testifies to a form of historical forgetfulness even Degrowth Advocates cannot escape. Because as right as the reference to thermodynamics may be, it is as wrong to want to bury the intelligence factor under the given subject material. If you have to consider them, the idea of the absolute limit has vanished into thin air, no, into a vacuum. Since there’s no absolute above the sea of air – the horizon of society and its time, therefore, lies in its knowledge of the world – and, as a result, a resource-fixated view necessarily misses the paradigm of Modernity.

In essence, the Post-Growth economy denies something very simple: namely, the logic of the Machine. This is by no means an achievement of the industrial age, but it goes back to antiquity, which translated mechané most aptly as 'defrauding of nature.'11 And, because in this realm’s register where the discovery of vacuum produces a renewed innovative thrust, all recollections regarding the Limits of Growth, the Earth Mother Gaia, and the Anthropocene miss the truth; the simple fact that, with a vacuum, the cunning of the Machine triumphs over nature – yes, even a sober concept of nature, freed from demons and spirits – is, without this fraud, a thing of impossibility. Here lies the critical error of the Post-Growth economy. For in denying the mechané, the Degrowth Advocates undermine the raison d’être of Modernity in the first place. To prove this, it is only necessary to look closely at their slogan of less is more. If they want to remind us that the happiness of the human race lies in resource conservation and a new frugality, this admonition to turn back is proof they’ve missed the essence of modern progress – and fundamentally so. For the apotheosis of minimalism undercuts the Plus intra, along with the fact that the less goes hand in hand with an increase in intelligence – which means using limited resources in ever more intelligent ways. The fatal consequences of suppressing this engine [Triebwerk12] only becomes apparent when you consider the political implications of the cure of shrinking economic growth. Because if humanity is condemned to save, it goes without saying that the coming generation has to prepare for losses. With it, however, the promise of transcendence is dispensed with. If Capitalism is understood as a secular world religion, the termination of the promise of growth can be equated with the death of God – an announcement that must shake the contemporary couch potato, the consumer, to their foundations. Still even more fatal than the shaking of the foundations of faith are the political consequences of such a statement. Because if the hope for an improvement in living conditions is vain and delusion, indeed, if the population isn’t voluntarily prepared to do without, this task – the management of scarcity – must be handed over to a suitably qualified elite. The enthronement of such a command economy means no more and no less than a level breakage moving outside the rule of the law’s normalcy. For the rationality (headlessness) of the market, where the egoism of the individual, as if guided by an invisible hand, miraculously enhances the common good, must be replaced by a political authority. But because the spectre of a new command economy rears its head here, the question of sovereignty arises: who is authorized to manage the shortage, and with what mandate? While this may not cause the Last Generation, as the avant-garde of the revolution, the slightest headache, inventorying the shortage is already a problem. In retrospect, haven’t all the warnings of doom proved untenable – simply because they extrapolated a present into all futures? One need only recall that Paul R. Ehrlich, in his Population Bomb published in 1968, predicted millions and millions of deaths as early as 2000 – just as Dennis Meadows’ simulations proved untenable. If one tries to identify the blind spot underlying these misleading predictions of the future, it lies in the fixation on the available material – and the fact that any growth in world knowledge is banished from the equation. Instead, one clings to an old, materialistic conception of the world, which lets the incredible growth of intelligence fall under the table in the rigid view of limited natural resources. INTEL co-founder Robert Noyce summed up this blind spot nicely in a lecture from the 1980s.

If the progress of information technology were to be transferred to material space, a car trip from Silicon Valley to New York would not take a second and would not cost a cent – and the tiresome parking problem would also be a thing of the past. Once in New York, the user would simply stow his car in his pocket.

This example illustrates two dichotomously competing and, even more so, diverging ideas of growth. If one movement follows the PlusUltra of modern times, the other flows into the Plus Intra. The pandemic has already provided an excellent exemplar of this. If you’d asked a pre-Corona contemporary whether it would be possible to maintain Capitalist business as usual with a tenth of the previous air traffic, you’d probably have expected a bewildered, if not pitying, look. But if the pandemic (more precisely: the company Zoom Technologies) has shown something, it’s that not every foreign flight is a strict necessity; indeed, that telematic communication is sufficient in most cases.

Because the Advocates of Post-Growth economics – in their assertion of the zero-sum economic game – underestimate the modern concept of growth’s reversal within the Plus Intra, they risk falling back into an ultimately reactionary position of a neo-Malthusian worldview. This doesn’t mean the diagnosis of Capitalism’s living beyond its means is inappropriate – just as one can’t dismiss the criticism of a consumer society indulging in ersatz gratification. Nor does it cast doubt on the assessment that an economy knowing no other value than self-created money runs the risk of getting lost in the labyrinth of its phantasms. (One would have to be a fool, by the way, to dismiss these criticisms). But, on the other hand, the intellectual toolkit is doubted and declared insufficient, which completely undercuts the digital society's decisive Engine [Triebwerk]. If the less is more isn’t aimed at increasing intelligence but at humbling oneself, the baby is thrown out with the bathwater. In this sense, one could claim (paraphrasing Karl Kraus) that the Degrowth movement is the very disease it thinks it’s treating. This may be a biting judgment, but it only points to a widespread form of operational blindness that’s virtually cultivated among its experts. That, in their fixations on the evil to be eliminated, the critics of a grievance repeat it in symbolic form is probably the deepest reason for the déformation professionelle. Consequently, the prophet of scarcity can only preach scarcity while remaining blind to the fact that his cure of economic shrinkage undercuts the solution to the problem. It is no coincidence that the Degrowth Economy Advocates join the world’s Luddite League, which has placed the digital operating system’s unleashing under general suspicious – and in doing so, are depriving themselves of a growth process whose goal is not an ever-escalating battle for materials; au contraire, it is an ever-smarter exploitation of the given. But what, and this is the question, is this fascination with scarcity? What is the seductive power of a thinking that can be understood only as a repentance sermon turned into secularism, a sermon that does not know how to preach much more than repentance and conversion? What is the cui bono of such an attitude to the world? Well, first off, it’s probably that this posture shows you have an attitude toward keeping the Plus Intra at bay. Because, given the exploitation and devastation of nature, you’re inevitably inclined to ally yourself with the desecrated earth mother while equally declaring the grievance grifters sinners. In this context, the Limits to Growth can be manipulated as an absolute standard. In any case, anyone referring to it can feel as if a higher power has ordained them. Given this self-empowering act, in which Gaia’s defender becomes the voice of a desecrated, muzzled earth religion, it’s understandable why the newly ordained priest only condemns the digital operating system as the latest symptom of a deep intellectual aberration. After all, doesn’t constructing a chip factory also involve an enormous material expenditure? If you look into the question, you’ll see this plea for a digital detox is little more than a lazy excuse – and that it puts you in the company of those who shun digital literacy as fervently as the devil shuns holy water. For with digitalization, the horror vacui of Modernity has been touched, the fact that Modernity’s level of abstraction leaves a deep sense of unease (vacuum, electricity, quantum mechanics). Not only is it arduous to enter into the logic of Plus Intra, but it also requires the adept to sacrifice several cherished beliefs and articles of faith. And because this would involve a loss of privileges, large sections of the population are not interested in this – indeed, they are busy trying to prevent the triumph of artificial intelligence. All you have to do is perform a little thought experiment. Imagine a government determined to digitize every administrative act consistently and every routine official task. The result would be easy to predict. Because all these administrative processes, transferred to a digital program, would disappear into the museum of work, the administrative apparatus could be consolidated into a state machine that, with the same, if not significantly improved, performance, would only need a fraction of the human personnel. And because this threat is in the air, it is not surprising that a general Katechon attitude has developed, a spirit of resistance in which public servants indulge primarily in the simulation of productivity and irreplaceability – while, conversely, they’ll do everything they can to fortify the institution against novelty and innovation. Considering this explanatory foil, the Degrowth movement joins in with the front of resistance in general. And it’s for this reason – not because of their justified criticism of consumption – that their reversal sermons are reactionary. To avoid looking the horror of progress (which leads into Plus Intra) in the face, you preach conversion. And why? Because a known evil can be preferable to an unknowable and threatening future. Here lies the basic paradox which is simultaneously symptomatic of the loss of reality: the augured promises of negative growth are not imminently ahead of us; instead, they are in the form of Plus Intra as the law of Modernity’s movement in general – and every computer chip, every smartphone can be understood as an apotheosis of this thinking.

Translation: Hopkins Stanley and Martin Burckhardt

John Kenneth Galbraith: The Affluent Society. New York 1958.

Here Martin refers to Carl Schmitt’s thinking of Political Theology, where using an act of speech to declare reality allows you to thwart any objections and declare a state of emergency, enabling a movement to step outside the normal legal order. See Burckhardt, M. Carl Schmitt and his Heirs, Ex Nihilo (Substack), Nov 26, 2022, and On Sustainability, Ex Nihilo (Substack), Dec 9, 2022. [Translator’s note]

Erlich, Paul R., The Population Bomb, New York, 1978 [Translator’s note]

See Meadows, Donatella & Dennis [and others]. The Limits to Growth; a Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind, New York, 1972. [Translator’s note]

This is an idea already brought into the world by Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker when he fixed information (as the increase of mind) as the entropic counter-concept.

The existence of a vacuum as an object in a void has been debated in Philosophy since ancient Greek times. However, it wasn’t until 1643, when Evangelista Torricelli produced the first actual vacuum in a laboratory, that an imaginative period of intelligent and inventive thinking sparked the beginnings of the Scientific Revolution with a rapid increase and accumulation of scientific knowledge. [Translator’s note]

This is a thought that is the starting point of my Modernist narrative in Über dem Luftmeer, which will be published in May by Matthes & Seitz.

This was the motto of Charles V, which he included in his coat of arms and which can be read as the motto of the conquest of America.

This slogan is from Richard Feynman’s 1959 There's Plenty of Room at the Bottom presentation, where he predicted the emergence of what we now call Nanotechnologies in the late 1980s-early 1990s. Here, the critical point is that shrinking technology to use less material seemed impossible, but as Modernity’s underlying basis of Plus Intra continued developing and accumulating human knowledge, it became possible, reflecting the Impossibility of the Possible. [Translator’s note]

This refers to the mighty potency of our emergence as humans in the anthropocentric shift from autoplastically adapting ourselves to the environment into alloplastically dominating and yoking it to our needs; this disenchantment of the natural world is how the Machine defrauds nature using its machinations. Tracing its rise and sneaky obscuration begins with the pre-historical pre-Indo-European root word *magh, meaning to be able, to have power, as it moves into the Greek mechané that is the freeing of the imagination where it becomes the Universal Machine’s veiled pulsating powerhouse [Kraftwerk]. Here, the imagination provides the metaphysical battery of the Greek miracle, with its techné grammatik, that formalizes the Machine’s deceptive Worldly demagicification as it bends, shapes, and en-structures the natural world for our domination through the concealment of our veiled forgetting [letheia]. See Burckhardt, M., Philosophie der Maschine, Berlin 2018. [Translator’s note]

Triebwerk is the Engine of the Universal Machine’s Social Drive [Gesellschaftstriebwerk], powered by the Imagination’s intelligence [Kraftwerk]; see fn. 8 above. By suppressing this Engine, the Degrowth Advocates’ push to use less to do more clogs the Social Drive by stifling the Imagination’s ability to intelligently create something out of nothing [Ex creatio Nihilo], hence, discover more efficient ways to use materials.[Translator’s note]