The concept of Sustainability has rapidly grown since the 1970s, becoming socially pervasive. And because this proves one's future viability, no politician fails to adorn their speech using this boilerplate. What's more, some countries have even gone so far as to elevate sustainability to the rank of a constitutional principle.1 So, who would have any objection to establishing such sustainable solutions? Considering this all-encompassing sense of social connection which knows neither races, castes, nor nations, sustainability seems like the most commonplace of all platitudes, a 'container concept' used by the most diverse schools of thought. Now this rubrication, which leads to the association of containerizing (the dumpster diving), may feed the suspicion that we are dealing with an intellectual garbage can here; in any case, the question arises: What does sustainability mean if you are dealing here with a mental garbage can? And the question comes forth next: What does Sustainability mean if you don't content yourself with merely longing for eternity (Oh, just a moment, linger!2)? The fact that yesterday's promises of sustainability have not infrequently turned out to be disastrous like the much-vaunted biodiesel which, for example, has contributed to the massive deforestation and destruction of Indonesian palm and rain forests, should give rise to a certain skepticism – as should the fact that the term has developed a radiance just as modern certainty about the future has shrunk. In this sense, a historian could read the rampant pathos of Sustainability as the very evidence of its opposite: that the more sustainability is demanded, the more our intellectual toolkit's usefulness has shrunk to the point that, by following the necessity of shortsightedness, we govern by sight.

From Kant comes the beautiful remark: "Concepts without views are empty; views without concepts are blind.” So, where does this concept of Sustainability begin? Although, while not explicitly stated in this form, the concept comes from Sylvicultura Oeconomica, or Home Economics, News and Natural Instruction for Wild Tree Breeding, written in 1713 by the Saxon chief miner Hans Carl von Carlowitz (1645-1714), in which he argues, roughly speaking, that one should promote the regrowth of the forest.

Such reforestation measures seemed sensible to Carlowitz because he stated that there was a "great shortage of wood everywhere and in general,"3 but, on the other hand, as the owner of a glassworks, he had in mind this question of energy and was convinced that "wood is indispensable for the conservation of man."4 Consequently, he suggested that, instead of producing wood charcoal, peat should be used as a heat source, and attention should be paid to the overall "equality between the increase and decrease" of wood. What is remarkable about this story is that the notion owes less to a particular romanticism of nature than it does to an energy requirement, namely that there should be a “continuous standing reserve for exploitation5”.6 Insofar as this reasoning follows an economic view, sustainability means creating a reserve that is available to fall back on.

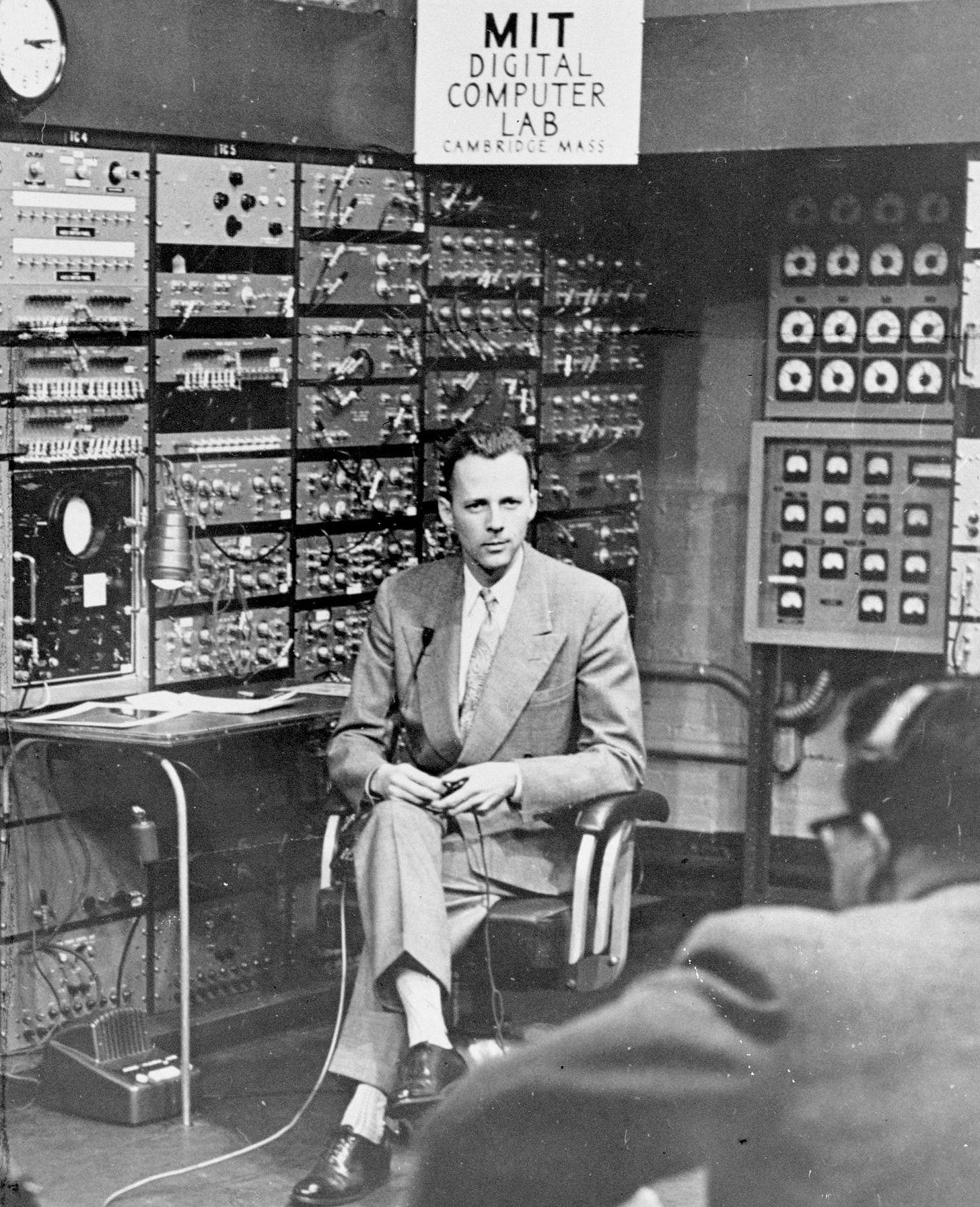

The fact that the concept of Sustainability – like the concept of capital – gets lost in abstraction is not accidental. That’s because assessing whether a particular practice proves sustainable only makes sense from a systemic point of view. Consequently, the notion of modern Sustainability appears over where the idea of the natural equilibrium (such as the forest) is transferred into a capitalist economy – as an expression of en-framing within the peculiar coinage of the word ecology. For here, the Nomos, meaning the natural order of the Greeks, is replaced by the Logos through a social sculpture. And this has little to do with nature and all the more with a human-all-too-human perspective, meaning the discovery that one has made the calculation without the host. This raises the question of how such an overall systemic view blundered into the world in the first place – and what implications it brings with it. More fundamentally: How can modern economic activity and natural exploitation parameters be modeled? This question brings into play a way of looking at things as far away from most environmentalists’ views as the other side of the moon. Historically, however, this is the conditio sine qua non. For what precedes the Club of Rome and the shock about the limits to growth? Nothing other than the development of modern computer simulation. It owes much to computer pioneer Jay Forrester, who invented vacuum tube memory in the early 1950s and used it to build the American air surveillance system S.A.G.E. – a network of some 35 surveillance points that together represented the most energy-hungry monster the world had seen to date (even though its aggregate computing power at the time was less than what a contemporary smartphone is capable of today).

In a remarkable career move, Forrester then went to MIT, where, at the Sloan School of Management, he set about transferring what he called the 'mental database' into an executable computer simulation. Analysis of a beer brewery's business processes revealed that even the simplest, economical methods (namely, proper estimation of demand) overtaxed the participants, resulting in the equilibrium of supply and demand being disrupted by so-called hog cycles. In this sense, Forrester's simulations were evidence of the limitations of human judgment, confirming what psychologist George Armitage Miller noted in his Magical Number Seven – that humans can only keep track of a very limited number of variables at any one time. In contrast, a computer model has almost no limits. Although Forrester's computer simulations depicted a series of logistical and urbanistic facts much more precisely than his social sciences colleagues could, his forecasts frequently triggered indignation – simply because they contradicted common sense. And because Forrester, guided by his calculations, predicted that the development of satellite towns with low rents wouldn’t benefit the disadvantaged working castes in the least; instead, that they’d lead to a form of ghettoization, he had an enraged colleague storm into his office, yelling he didn't care if Forrester was correct or not as, in any case, statements like these were unacceptable. Since Forrester's computer simulation proved exceedingly helpful à la longue, the Club of Rome, holding its first meeting in Bern, Switzerland, in 1970, took up Forrester's suggestion to use his System Dynamics for a world simulation there. Financed by the Volkswagen Foundation, 28-year-old Dennis Meadows was entrusted with implementing this research project. His model of the world and its future, which led to The Limits of Growth7, was based on a computer model of just five variables. And though his predictions weren’t wholly accurate, it only proves that even computer-augmented intellect can fail because of the complexity of a task.8 The book's worldwide success was not diminished by this. In some respects, it seemed like the era’s literary supplement to the visual sensation of the NASA photos of the earth as a circumscribed, blue planet – which was only because the transistor's shrinkage of space had made it possible to send a manned spaceship into space (besides satellites).

What is remarkable about the modern concept of Sustainability is that its location in computer simulations plays no part in its genealogy; indeed, it’s virtually suppressed. To put it bluntly: one allies oneself with the host so as not to have to reckon with the cost (how does Franz Alt say? The sun does not send us a bill). You can see this in the so-called magic triangles that have dominated the debate since the early 1970s – and take the following form:

According to this model, the well-being of humanity rests on the two pillars of nature (as ecology) and the social. The fact that this relationship is not innocent, but, per se, is a relationship of exploitation, is overlooked, just as the digitalization project of the post-war period could have been interpreted as a model, even as a blueprint for all sustainability efforts. This is because of the success in placing much more information within a silicon crystal (according to Moore's law), thus, greatly increasing its energy efficiency ratio (which, entirely incidentally, also led to the discovery of the solar cell). That the concept of Sustainability is instead wedded to the forest and a diffuse unease with modernity may have warmed the hearts of environmentalists, but it has also fogged their vision. This is because such an attachment to nature fails to recognize that a resource is only understood as such if it is significant within a technological environment. Cobalt, for example, has only shed its bad reputation because it can be used in battery production. Because it gave off foul odors when heated, the miners of the Middle Ages believed it to be the residue of goblins who preyed on silver and excreted the inferior, foul-smelling cobalt. One might consider this omission a venial sin, were it not at the same time connected with an intellectual gap – indeed, almost an unconsciousness that allows the concept of sustainability to slip into a magical register. Because only by suppressing the contemporary (and that means: the digital) operating system of Capitalism can we stride towards the re-mythologization of Nature, towards the Gaia hypothesis. This has (see the above biodiesel exemplar) nothing to do with real sustainability but more with the continuation of the Philosophy of History through other means. Having reached the end of history, the Hegelian Zeitgeist is unceremoniously replaced by Gaia – through that state of Nature which Bruno Latour wanted to write with a capital S. Because a religious desire is ultimately articulated here, it is not surprising that the climate disciples revel in apocalyptic images and figures of thought, displaying a severely limited capacity for concrete solutions in their activist millenarianism. And as Sustainability is in danger of devolving into a form of apocalyptic metaphysics, it is essential to develop a certain skepticism towards this sermonizing and preaching. A sober look9 shows that much of what is considered sustainable today will be the industrial ruins of tomorrow – a hazardous waste we do not know how to dispose of.

This is precisely what leads back to the beginning; to my astonishment that Sustainability has emerged precisely in that epoch where future thinking has taken its leave – and where you have been able to watch, as it were, how the discourses have spiraled downwards as they’ve lost the thought of durability. In this sense, Adenauer's famous statement: ‘What do I care about the things I said yesterday?’ could be interpreted as a kind of discursive self-empowerment, as a license to indulge passionately in one's wishful thinking. And it was precisely at this point that a reaction mode evolved within me, more precisely: a suspicion, which virtually takes a fundamental paradox as a given. Accordingly, a term appears because one is actually dealing with its disappearance. When we talk about Sustainability, we can only conclude that the people concerned must have lost any form of future certainty. In this logic (fair is foul and foul is fair), it no longer makes sense to get involved in the content of a statement. Instead, it is essential to realize that a behemoth is building up behind the shimmering monstrosity of terms – that which really wants to drown out the beautiful words. For example, if you witness the proclamation of the Education Republic of Germany, your first thought would be: For God's sake, how bad must education be there?! And this applies equally to the German Good Childcare Act, to the delegitimization of the state relevant to Sustainability’s constitutional protection, you name it. This is why Sustainability, even if it claims all the time in the world for itself, is nothing other than: The End of History.

Translation: Hopkins Stanley and Martin Burckhardt

This has been the case in Switzerland since 2000 but also is under consideration by Germany – as suggested by the expert opinion of the former President of the Constitutional Court, Hans Jürgen Papier. See Hans Jürgen Papier: Sustainability as a constitutional principle. May 2019.

This refers to Goethe’s line, “When I say to the Moment flying; 'Linger a while – thou art so fair!' Then bind me in thy bonds undying, And my final ruin I will bear!” from Faust. [Translator’s note]

Hans Carl von Carlowitz: Sylvicultura Oeconomica or home economics, news, and natural instruction for wild tree cultivation, p. 97.

Ibid, p. 372.

Ibid, p. 105.

It’s curious how Hans Carl von Carlowitz, as a glassmaker no less, predates certain deep ecological interpretations of Heidegger’s referencing of Ernst Jünger’s standing reserve here by 200 years. See Vincent Blok, Reconnecting with Nature in the Age of Technology The Heidegger and Radical Environmentalism Debate Revisited, in Environmental Philosophy, 11:2 92014), pp. 307-332. [Translator’s note]

See Donella H. Meadows [and others]. The Limits to Growth; a Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind, New York, 1972. [Translator’s note]

Similarly, all the models used to calculate climate trends are based on modeling software which, if it contains bugs, leads to seriously flawed inferences and predictions.

This is a topic requiring a separate article. Therefore, just as a reference: Mark P. Mills: Mines, Minerals and "Green" Energy. A Reality Check. Manhattan Institute, July 2020.