As Dalí started dreaming of WALL-E

About Dalle-E and how to move in the Game of Signs

Why a self-experiment with DALL-E? Perhaps because life is life-sized, and the clearest view of a thing comes from not owing any thing to secondary sources – only our own experiences. DALL-E’s quickly explained as the visual application of OpenAI. However, having acquired a particularly dark notoriety in the form of ChatGPT, its real developmental revolution has been obscured: it provides us with previously unheard of, even unimaginable, user tools which allow us to create pictures through the use of language – that is, through pure Power of Imagination. Ultimately, we're dealing with that situation which we’ve made clear in the examplary of Marcel Duchamp's Fountain.

The idea of image production completely detaching itself from craft is irritating and disturbing – yet it's a reality that, sooner or later, will completely change how we look at images, if not our worldview. Curiously, we find a recurring point of view here originating from the medieval theory of signs when the scholastics asked themselves whether the field of Signs has hierarchical order? If the Renaissance answers this question with the primordiality of pictures (Leonardo da Vinci, in his "Book on Painting," takes great pains in presenting painting as music's big sister)1 – then Scholasticism's thinking points in a completely different direction. The Scholastics believed the Sign, being closer to God, is of higher significance. Consequently, the thought has an almost divine meaning regarding its immateriality. The spoken word follows it – then the written one, and last but not least, comes the painted, the pottered, or an otherwise formed image of some Thing. The extent to which contemporary cultural studies still pay homage to this phantasm becomes clear remembering the 90s when one could still proclaim a visual turn. But because the wheel of time reliably continues turning, this turning of the mind has been given over to a merciful oblivion –thus, it seems that the only continuum is that of the progressive movement toward abstraction.

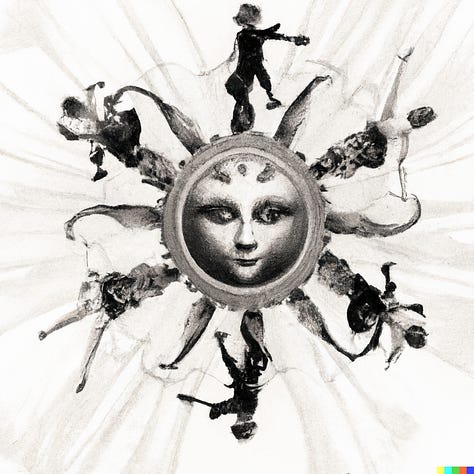

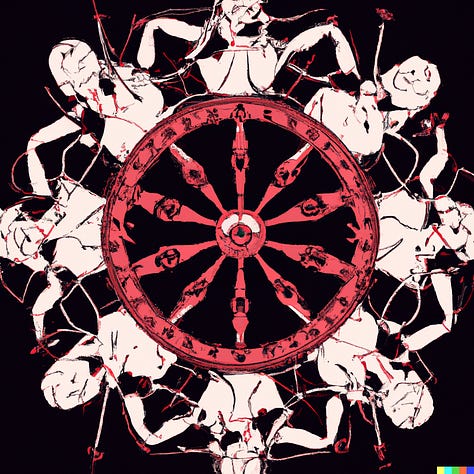

But now, on to the point! What do you do if you want to elicit a picture from DALL-E? You enter a line of text into an input field – and wait for the artificial intelligence's digestive system, the Mega-Fountain, to spit out something passably recognizable. For obvious reasons, this kind of configuration cobbles together representations that reality itself can't offer. Thus our first task for the AI: A wooden wheel whose spokes consist of human bodies – yielding this result:

We start imagining how such a picture could have come about, asking ourselves what would happen if we varied our query – so we ask for a mask-like representation of a deity as the wheel’s axle. And, for it to take on a more symbolic representation, we ask to transpose it into the world of 'primitives':

And then there’s the desire to be shown this picture in a Baroque style – leading to these somewhat strange results:

A trip back in time to the 14th century gives us this:

While delving into displaying further variations shows us these:

Since it’s already an ornamental motif, we ask ourselves what it would look like in a classical Greek style:

Then, because depicting bodies raises some puzzling refusals to digest some of our requests (apparently out of political correctness, DALL-E reacts irritably with hypersensitive responses to the word body) – so we immediately come up with a circumventing thought: What would the picture look like if you’re dealing with a skull whose spokes were actually bone-shaped? Of course, the answer doesn’t take but a minute – it looks exactly like this:

This response was most curious, naturally tempting us to request several variations at once – so we asked the software to engender images in the style of photorealism, resulting in something seemingly taken from Haitian Voodoo culture or the Mexican Day of the Dead:

But then, what would the wheel of humanity look like as seen through Pieter Breughel's eyes?

Or Max Ernst?

Or what if we commission a Marc Chagall to execute our ornamental motif as a stained-glass Church window:

And because the beauty of these results catches us off-guard, we find ourselves catapulted into architectural space as we ponder: What might this look like if we want to design a cupola in this way? DALL-E obliges, returning this very surreal image:

And the following intriguing variations:

The more intensively one becomes involved in the Game of Signs, the more the mind detaches itself from a specific solution. Inevitably, that’s how playing the game of free association begins – that’s how we almost inevitably find ourselves departing from our original notion, replacing the human body with something else – insects, for example.

And it’s most curious how this shifting of our request gives the whole project a familiar coat of paint – the curio wonder cabinets of science:

Or that one of us imagines the revered entity at the center of the human gearbox is no longer a deity – but now a rock star, surrounded by guitar-shaped spokes:

If this self-experiment with DALL-E teaches us anything, it's that a manual approach to image production is demodé – that the actual battery of image production lies in pure Imagination. Considering this, it becomes apparent the current debate over Artificial Intelligence, at least where it raises the question of replacing humans, misses the actual point. No, it is not about replacing humans with artificial intelligence. Instead, it’s about dealing with such a Wishing Machine of Desires; what's needed is a new kind of educational program aimed at unleashing our Power of Imagination. As the student revolt chanted: L'imagination au pouvoir.

Cyborg Psychology

One of the peculiarities of the Artificial Intelligence Discussion is this conviction that it's only about replacing the human being, while there's hardly a thought given to the fact that what we've put into the world is nothing other than a magic mirror reflection of ourselves- and that this instance will necessarily change our self-image as well.

Our bodies are still alive

A daily ritual. You get on your exercise bike, start cycling and let a YouTube sequence of some pop songs play — and suddenly, after a Lana del Rey track, this announcement pops up: Jim Morrison (AI generated) sings Video Games by Lana Del Rey. And then Jim Morrison's

At this point, the medieval concept of representare begins shifting into depicting reality as an act of representing as reprasentatio. If we recall that repraesentatio stood for the heavenly register of all the saved souls, this reveals a moment of secularization. Reality becomes a simulacral representation of what’s real, what is painted in such realistic detail that it fools the eye in its abstraction from reality.