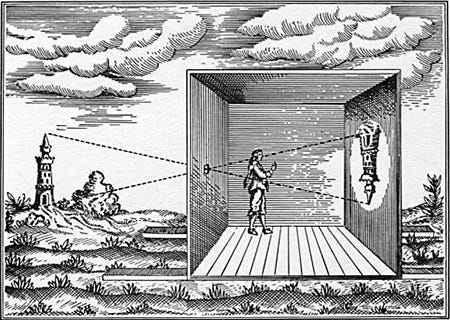

From Günter Anders comes the beautiful observation of the Promethean shame — that split in which the creator apologizes for his creation. In a contemporary way, this can also be taken from the statements of Geoffrey Hinton, the researcher who revolutionized artificial intelligence around 2012, using an anthropomorphic shape recognition operation to reduce the enormous amount of data previously required by machine learning1. The results of this humanizing action were so resounding that within a few years, the software revolution occurred now confronting us in the form of OpenAI, chat GPT, and DALL-E's automatic image generation algorithms — not to mention the countless applications offering text-to-speech solutions; AI-powered audio or video enhancement; or automatic translation. A success prompted this venture's spiritus rector to confess it was terrifying. However impressive all these results undoubtedly are, they have little to do with what you could call intelligence — namely, intellectual penetration. Instead, the researcher discovers in his magic mirror nothing more than the condensate of human intelligence, a kind of mass soul. Structurally, Artificial Intelligence works like the camera obscura of the Renaissance, which mechanically presented an engram of reality that the artist (squatting inside) copied onto his canvas — with the only difference here is it isn't the outer nature, but an image of the collective soul appearing in the magic mirror — of all that has already been thought, said, done.

Just as the painters of the Renaissance used this new image-processing technology for their purposes with the greatest of ease — exemplary is the forms of mobile camerae obsurae with which landscape panoramas could be recorded — it's clear these new kinds of tools will also become part of our social life. And it is equally clear that many of these skills today still covered by artistic aura will lose their social (and economic) esteem — while, conversely, the intelligent, intellectual use of these tools will become the actual object of creative work. Marcel Duchamp demonstrated this process in its paradigmatic form as early as 1917 with the exhibition of his Fountain Urinal.

The artist’s personal contribution was limited to the signature under his artistic Avatar as R. Mutt – 19172 and a 90orotation of the object itself. Duchamp referred to the artwork as a ready-made — signaling that it wasn't the object itself but its perception that constituted the actual work of art. We can already recognize in this slight shift the birth of the Attention Economy — or, more generally: the conceptualization movement of modern art, in which the work of art (the exhibited perception) becomes a social act.

If we contrast this form of aestheticized perception with the Attention Economy practiced today as a Capitalist rationale, it's striking that the latter isn’t interested in refining the gaze but only in making the object of desire completely streamlined and compatible with the masses. The goal is the mass product — or, more precisely: the absorption of a mass potential for attention. This means that everything incomprehensible and unintelligible is culled and weeded out. Only in this way can you enter into the trending and feeding back process of virality, that perceptual circulus vituosus in which always already existing expectations, partialities, and biases are continuously served and confirmed. As observed over the last three decades, the consequences are this progressive decline in quality and a consistent lowering of expectations. This not only affects cultural artifacts but is also reflected in our declining level of education — which in turn has direct repercussions on the world of professional work-life. Expressing individual beliefs is replaced by calculation, a calculus of quotas compelling the individual to behave according to prescribed rules, competencies, and compliance requirements. To put it disparagingly, this textbook performance acquires an android characteristic — a demeanor that can be studied in vivo in the comportment of call center employees. Structurally, this corresponds to machine learning logic, with the individual being reduced to a socially acceptable pattern, a living coinage, if you will. This striving for formatting is directly observable in the education system itself — which, with its constant evaluation of progressively detailed course modules, aims at reproducing a pre-defined set of specified competencies. The fact that the humanistic ideal of education — with its appreciation of the individual — has had to be buried in the modularization mania becomes collateral damage, even priced in as an inevitable cost. More troublesome is society's need for this formation amounts to reproducing the Machine's Ideal (euphemistically titled as 'canonization' or masked as competence). Crucially here, as in the case of assembly-line production, the discours de la mèthode are predetermined, and the teacher is nothing more than the executive organ of its delivery. An exceedingly absurd example of this technique is the multiple choice test that has flooded educational institutions since the 1970s. Initially developed by B.F Skinner as a kind of stimulus-response apparatus, its objective was to give immediate feedback to the student interacting with a teaching machine — in other words, what computer games have achieved in hindsight. That this machinery didn’t win its triumphal march in its original form, but on paper, is an irony of history reminiscent of an episode from the time of the first printing press. Because the monks in the 12th century had already designed a sophisticated system of Bible editing, their reaction to the delivery of a Gutenberg Bible was precisely just this: Each monk took the Bible passage he specialized in and checked it for printing errors — a job repeated on each and every one of the books delivered. And just as the monks confirmed the logic of pecia with this action, transferring multiple choice to paper affirms that even where you sacrifice humanism to the Gutenberg galaxy, you remain wedded to its techniques — a digital illiteracy, if you will.

If you analyze the initial conditions that the AI revolution is encountering , you can call it a perfect storm. For artificial intelligence is approaching a society suffering from a crisis of values in several registers at once, one that, instead of opening itself up to the future, is exhausting itself in maintaining a dysfunctional Social Machine — an operating system that cannot deny its imprint of the mechanical world view3. The computer pioneer Charles Babbage already analyzed this fact very precisely in his On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures4. Because the longer a society refuses the Machine's Rationality, the greater the potential gap and the more shocking the replacement of human work by the Machine's program becomes. This is precisely the current situation — explaining why just playing with Chat GPT causes a kind of intellectual jolt — why teachers or professors are pondering whether the assignments their disciples are turning in could be machine-generated. If these fears are primarily a sign of how far the educational practice has moved from its emphatic educational ideal, they also reveal a second fundamental error — the idea that artificial intelligence could be anything other than a magic mirror.

This fixation on the eerie Golem’s existence might make fabulous material for a gothic novel, even a digitized Frankenstein remake, but it obscures the fact that we aren't dealing with an ethical dilemma here — and, above all, with a question of rationalization (and this is what burns on the nerves, especially where reason fails). Whenever the computer world successfully substitutes itself for human activities, it happens wherever people are content with performing average mechanical routine work. And because any work that exhausts itself in routines can be digitized, it will disappear into the museum of work sooner or later. If the advantages of presence teaching were painted on the blackboard during the Corona crisis, the educational catastrophe now significantly coming to light testifies that a teacher's presence alone isn't enough — significantly if their role is reduced to simply being an assistant instead of a teacher. If we were to seriously undertake the task of exploiting society's potential for rationalization, this would probably be tantamount to a form of societal self-dismantling — it is to be feared that the potential for savings would be far greater than was the case with the introduction of the assembly line in the 1920s. Perhaps even more fatal than this rationalization shock could be that under the conditions of the Attention Economy, there is little incentive to engage in elaborate world improvement projects. Instead, we’ll (have to) prefer the substitution of machines for people.

Actually, under the present circumstances, it is doubtful that the possibilities of artificial intelligence will unleash what the computer pioneers of the early days dreamed of: an augmentation of the world's intelligence. However, allowing yourself to take this Utopian view instead of indulging in its dystopias could paint a very different picture. Because if you understand AI as a form of the subservient mind, as a personal assistant now accessible to everyone, it is evident that this assistant can render the most astonishing services to its master, and even more so because the assistant has unlimited patience and an almost inexhaustible memory — which predisposes it not to be merely a humble house servant, but to be a reliable everyday companion. Unlike the teacher, who faces a class (a cohort of students), you are here dealing with an initial situation entirely individualized for a single person. And this allows the assistant to focus on the specific quirks, idiosyncrasies, and distinctive personal characteristics of the individual while simultaneously accommodating all of them. Or, to put it another way: the private tutor of the privilege of the propertied classes in the education-assiduously loving 18th century can now be democratized. Now the personal assistant has a significant advantage: unlike the teacher, it has unlimited time and patience — and most importantly, being endowed with almost unlimited memory, it can adapt to its specific protégé. Because the interactions are stored and metricized, speaking of an educational curriculum for the first time becomes possible. Here, not only the individual user but the authority behind the program is also evaluated. And this raises the crucial question left out under the Attention Economy conditions: What image of humanity is this education effort being aimed? It’s evident the mediocrity that’s been pinpointed (the so-called artificial intelligence) cannot be the frame of reference here — but that we must go beyond it. As Marx already has formulated most aptly, added value is created only by man. But, because under the Attention Economy’s conditions, a limbo economy has emerged5 — furthermore, because the deep value crisis of the industrial societies has not even been spelled out in its approaching forms, it's to be feared what liberation from monotonous, routine work prevails, it could be in the form of a deadly, destructive perfect storm.

Translation: Hopkins Stanley and Martin Burckhardt

The fundamental question of Hinton, differentiating itself from the back-propagation stratagem, consisted in how to equip a computer with a capability coming close to that of innate human recognition; because the latter, unlike a classical machine learning algorithm, requires only a small number of examples to recognize a pattern. See Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, Hinton, G. - ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks, in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 25 (NIPS 2012), ISBN: 9781627480031.

The name referred to the company Mott Iron Works on the one hand, who manufactured the work, and on the other hand, to a popular character from Bud Fisher's famous American comic strip, Mutt & Jeff.

Here, Martin is referring to the Wheelwork [Räderwerk] driving the old Universal Social Machine [Gesellschaftsmaschine] and the interregnum between its transitioning over to the new one, that of the Computer and its’ oscillating Digital Drive [Digitalwerk]. [Translator’s note]

Published in 1832, Charles Babbage’s work is considered the first work on operations research, including the division of physical and mental labor, and was studied intensively by Karl Marx. It was written when manufacturing underwent rapid development and radical changes in its processes. See Babbage, C. — On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures, Cambridge University Press, 2010. [Translator’s note]

Here is a lecture I gave on this subject in 1999 shortly after the publication of Vom Geist der Maschine in 1999 —

— and the English version of an essay that first appeared under the title Im Arbeitsspeicher in 1990 in a book on the social philosophy of industrial labor: