The following text is an invited lecture on Gender Studies to an Academic group of Feminists in 2000 at the University of Innsbruck, six months after publishing Geist der Maschine1. After re-reading the text, we realized its prescience in how it thematized a new, dialectical concept in which culture doesn’t appear as a possession but as an Angel Maker—a desiring Machine going hand in hand with the loss of nature within the opening of the Occident. In one of Martin’s typical ›Cultural Psychoanalytics,‹ we see how the appearance of a symbolic, or more precisely, an Alphabetical Order recodes our questions of Gender, Religion, and Philosophy – and how the dogma of the Immaculate Machine (the receiving of God’s word into Mary’s ear) can be read as a form of desire, culminating in the University, Book Printing, and the Enlightenment. This train of thought becomes wonderfully sophisticated in how he transfers historical insights into Modernity’s present discontent with itself—or rather with ourselves. Read against this psychotopic backdrop; we get a more primal understanding of the intense debate surrounding transsexuality. Or, as Martin writes, with a view to the dawning computer age:

It's about stripping away the earthly body to take possession of a higher, transsexual corporeality.

Hopkins Stanley

Martin Burckhardt

Birth of The Diva

Why culture is an angel maker

Ladies and gentlemen,

Now, I've associated the »Injured Diva« with Caligula’s Sister—while hanging behind her the sinister portrait of Culture as an Angel Maker—and right away in advance, I’m admitting that with this preamble, instead of desired enlightenment, I’m presenting you only enigmatic images. This is further complicated by the fact that the heroine of this lecture makes only a brief guest appearance before immediately disappearing inside the metaphor. So why, despite all this, did I choose such a title? For one single reason: I didn't choose this title, but it was bestowed upon me. Searching for the word’s possible etymological offshoots, I read that Drusilla2, the Sister of Caligula, was the first—albeit posthumously—to be honored with the title Diva: Diva Drusilla. Already, this opens on an interesting tradition since the story tells us of a mésalliance between ethereal transfiguration and raw violence – that the bizarre pairing of a Callas and an Onassis shouldn't be considered an aberration, but instead read as a structure, as a kind of law of mating. That's how this misfortune, which befell the diva through the form of her brother, isn't a misalliance but an alliance in which something deeper relieves itself out, namely that fundamental tension from which the diva initially arose. One could ask whether a diva blessed with indestructible health and radiant integrity is conceivable? The absurdity of this question makes it clear that the wounded diva – whom has lent her fragile image to this event – is already a tautology: quite obviously, vulnerability belongs to the diva; she becomes a diva precisely because she is vulnerable and mortal. Now if we can turn this perspective around, we would be looking on from the eyes of a young Caligula, that notorious butcher of men who crowned his tenderly beloved Drusilla as a diva. And so it's clear that the diva is a kind of miracle—or wound ointment—that's supposed to heal what’s incurable. It’s evident that Drusilla's divinization is a kind of proxy action. To divinize the sister is to divinize oneself, which means to suspend that existing-to-die, which can be understood not only as life but also as an incurable illness.

The Birth of the Diva – follows upon a dictum of Benjamin's, who said there is no act of civilization that’s not also an act of barbarism.3 Even if only conceded experimentally, the path to the Angel Maker’s figure isn't far behind. What is meant by this? Let’s take, just as a symptom, the figure preceding the opera diva. Here we have the castrato, who conquered European stages in the 16th century whilst seeking to appease the unholy melancholy of Philip II. There is, for the sake of an angelic voice, something else aborted – or, to use a terminus technicus, ligated—because factually, we're not dealing with an act of excision, but with an operation in which the sole aim is achieving the desired vocal miracle - and it's enough to tie off the boy's testicles.

What is the desire? Why undergo such an operation? As a preliminary answer, I'd like to assert that it's about a desire for transsexuality – whereby I understand trans-sexual quite literally: as something moving beyond sexuality – a conquest of biological sexuality. It's about stripping away the earthly body to take possession of a higher, transsexual corporeality. This observation coincides with the castratos' historical reality. Strangely enough, the castratos were by no means, as one might have assumed, desexualized, pure voices—but functioned as sexual symbols: the audience was full of men and women who longed for physical contact with this being – despite everyone knowing about their infirmity.

The castrato is also a good exemplum because it clarifies that nature, aborted here, isn’t a privileged female. But that means: if culture is an Angel Maker, then it's not limited just to the popular sense but is also on a metaphorical level. It stands for the dialectic of aborting nature for the possibility of culture: that there’s no cultural act that isn’t also an act of barbarism. Using a psychoanalytic term, you could also say that every sublimation has a price. It’s precisely this relationship that interests us about the diva—that she’s the battlefield on which conflicting positions become visible. But what’s this conflict? And what is its driving force? I’d like to introduce an intellectual triangle here, which you’ll find as a subtitle in Sylvia Eiblmayer's Hysteria, Body, Technique4. This triangle is much older than you would think, originating at the turn of the first millennium BC. This was when the alphabet was introduced – and Greek culture learned to function in a purely symbolic circle: en kyklos paidein. From now on, the Signs no longer refer to things but to themselves. This is where the megalomaniac idea arises that there's something everlasting, divine, metaphysical —and that man can possess it. If you read Plato's Cratylus, you'll find the line of argument that makes the alphabet appear to be the divine original language—a point worth pausing on briefly. Socrates claims that the right of naming originally comes from the gods, from the high-flying celestial beings. As Socrates etymologically demonstrates, the name of Zeus, as an exemplar, already reveals its true essence: as a giver of life and a pure, unclouded intellect. Following this etymological program, the world of heroes can also be read symbolically: »so that the heroes mean speakers and questioners,« and »this whole heroic tribe becomes a race of speakers and sophists.« And then his opponent, who, as we know, is little more than a prompter, says: »It may well be that language was once divine, but humans have corrupted and contaminated words through their use«—thus invoking the problem of the confusion of languages. But Socrates doesn’t dispute this, as he readily admits the erroneous use of words has disfigured them—but this doesn’t apply to the letters. In the letters, he explains, the original driving forces are contained. The »R,« for example, is the element of the rolling, the stirring, the organ of movement – and along this line of thought, each letter has its elementary function. Even if incorrect use has corrupted the correct names, it’s still possible—by understanding the original, divine meaning of the Signs—to determine the correct naming, meaning the original language can thus be reconstructed.

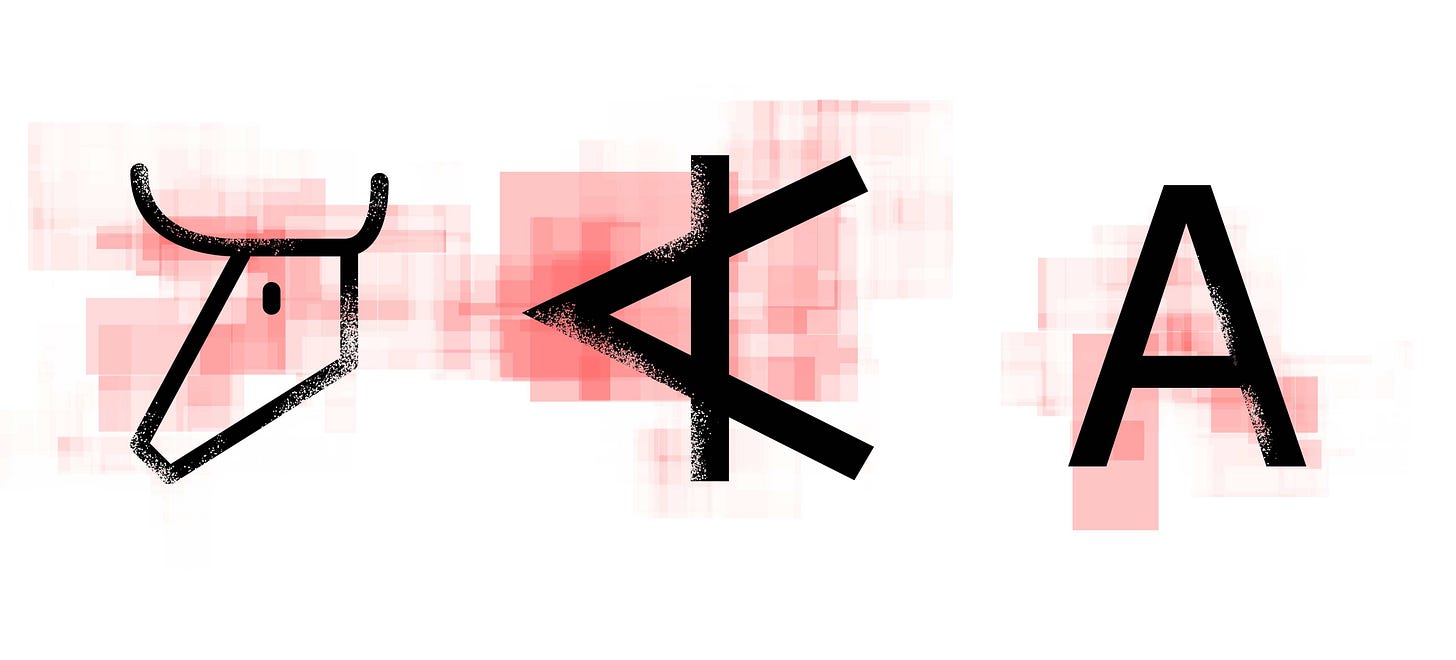

In short, with Socrates, the Alphabet becomes a symbol of the divine, a kind of genetic code, a DNA. This logic has been retained to this day, and it’s called metaphysics or the Language of Nature, depending on the case. However, Socrates' pattern of argumentation reveals his Sign’s hoax – as we’re dealing with an a-Logic, a negation of logic from the very beginning. But what prop is Socrates using here? That »A«is empty; it's nothing but A=A. But this isn't true—just take that capital »A« and turn it upside down. What do you see? Two little horns—and a bar between them. And the meaning of this sign is the Ox in the Yoke—this is the Hebrew translation of Aleph, but it also applies to the entire Mediterranean civilization of the 2nd millennium B.C.

Take the letter »B,« Beth, Beta, and lay it on its side. Beth means the leg in Hebrew but also represents the female breast. You can still see it.

So when Socrates claims that the letters of the Alphabet originate from the high-flying celestial beings, a divine code reveals itself here: this is a blatant act of repression, a repression of the fact that each Sign once had a body. Culturally speaking, an incredible rift appears, one we’re dealing with every day. If you talk to a Systems Theorist about signs, be it Money, the Alphabet, or the Logic of Zeros and Ones, he'll tell you, in the Saussurean tradition, these are self-referential, autological systems and that here we're not dealing with references to the world, but with arbitrary Signs. When I hear something like that, I open and search the etymologos—the authentic logos—and look under arbiter. Arbitrarius means random, arbitrary - just like the Systems Theorist told us, but arbiter is a strange word. First of all, you have the eyewitness, then you have the mediator and arbiter - and finally, the leader and guide. But the last meaning is quite strange because it means: executioner.

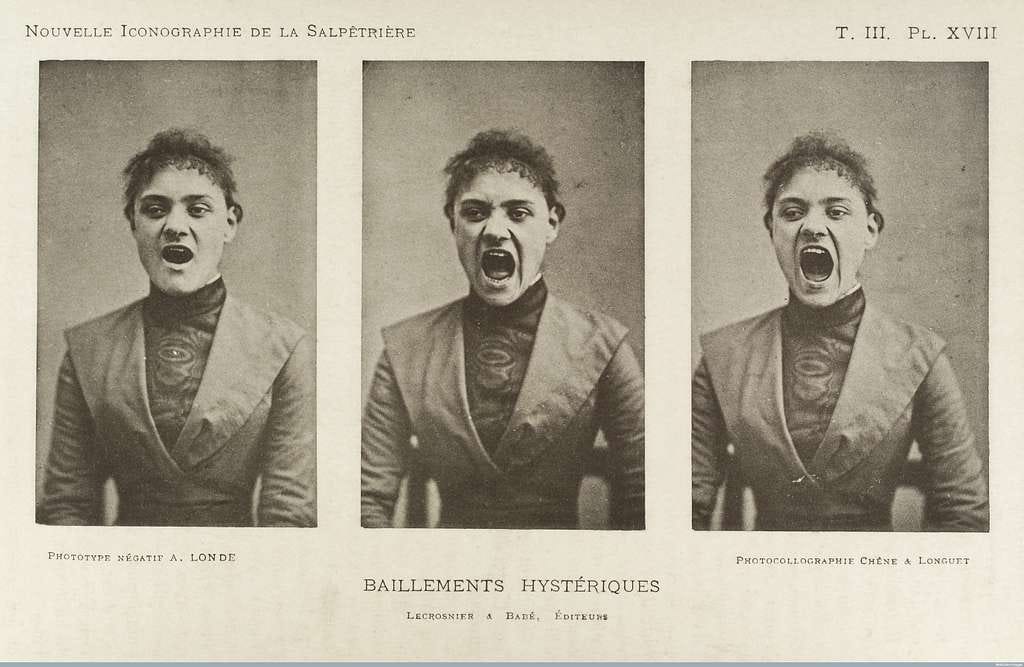

What is the connection? In principle, it’s easy to understand. Imagine I'm the Chinese emperor with the privilege of arbitrarily designating characters since I’m the first to print paper money. Because writing a number on paper is so easy, I write out a banknote and offer it to you. But you will politely decline, especially if the amount is so high that you can never cash this note. And it’s not unlikely you’ll refuse to give up your beautiful house for a scrap of paper. But what happens then? We're confronted with the arbitrary Sign’s logic, which, mercifully, the Systems Theorist has spared us—because not accepting the Sign is deemed an insult to the King and punishable by death. Incidentally, this is not a Chinese peculiarity. This was still the case in Europe’s early modern period, where non-acceptance of a sovereign mark was punished with imprisonment or forced labor in the galleys. In short, behind the arbitrary Sign lies the threat of death. And when Socrates divinizes the letters, there is something unfathomable behind this metaphysics—or this A-logic of negation as I would call it—an impulse to abort that which isn't beautiful, true, and good – and also un-angelic. I’ve described the Alphabet as a Symbolic Machine – and in this word, I believe, lies the driving force behind the problem we confront in the wounded diva’s form. Mechané – the Greeks saw this as a »betrayal of nature. « This is precisely what comes into play with the Alphabet, where the body is disposed of for the sake of ideal purity. Perhaps it becomes clear why the Greeks, these A-logicians, posited that nothing can come from nothing. This is, of course, a specious proposition since all of culture emerges from this nothing. If the sentence has a meaning, it lies in the collective deception of nature not being allowed to become apparent, that the price of the arbitrary Sign shouldn't be felt. Now, as we know, it’s not only Western culture but also its most faithful companion, Hysterika, arising from creatio ex nihilo as the other side of the Logos, the embodied speechlessness, aphonia. The hysteric dreams the dream of the Machine—in this, it's thoroughly indebted to the culture of the angels – but this is also how the Angel Maker side of this culture comes to the fore. In this sense, the very engine of culture itself comes to light in the deception of the hysteric since it follows precisely the same law: how do I deceive nature?

If, for the sake of argument, I were to summarise this schematically – I'd state that with the Greeks, the desire for metaphysics came into the world. Incidentally, when Socrates believes that, with the Alphabet, he has a divine language in his hands, he’s already anticipating antiquities' Twilight of the Gods—as, after all, intoxicated by the thought, we will be able to think of ourselves as gods. Nevertheless, the human race’s desire for divinization had to mature for a while before it dared emerge in all its simplicity – roughly around the turn of our era. At this point, I could return to Caligula's sister – but I'd like to contrast her with a contemporary who, unlike the diva Drusilla, wasn't just deified by her unhinged husband but had a genuinely triumphant career. Who am I talking about? The answer is Madonna. Yes, that’s right, Madonna, who, in my opinion, is the first and perhaps most momentous prototype of a diva. Now, to trace this career, I must confront you with this lady’s shortcomings and handicaps – because this story only becomes plausible by keeping the initial conditions in mind.

First, we need to correct our idealized view of Greek culture. Because here, too, we're dealing with what I see as a one-sided criticism of Christianity: namely, hostility towards the body. Just look at the etymology of the Greek word sarx, which means flesh. But sarx also means sarcophagus or coffin—but that means you’re as good as buried alive in your own body. Keeping this dichotomy in mind, you're constantly trying to glorify the body in symbolic form, as a sculpture or a verse – but at the same time, being aware of the mortality and impermanence of this body. That is the Greek tragedy – and it brings the cross onto the scene as a solution, to cross heaven and earth, to marry physis and meta-physis and let them become one. Nothing could be simpler: you just let the Son of God descend from heaven and take on human form. That’s how it happens in the Gospel of Mark, where there’s no mention of a virgin birth—but that of a dove sitting on Jesus' head and a voice from God calling out: »You are my dear son, in whom I am well pleased.« But a God who becomes man really isn’t the point – instead, it’s the other side of this chiasm: the man who becomes God. But how do you do that with this human material? The thought that God might have come into the world through the womb of a virgin is so offensive that you're willing to think anything but God in the Flesh—because that's an absurdity, an unnatural state. The God introducing himself this way violates the dress code. If there's a halfway decent way to enter the world, it's not through a woman's womb, but, like the goddess Athena, out of your father's head: a spotless head birth. This is the source of Gnosticism. Because the gnostics don't want god to be contaminated by the flesh, they claim he passed through the virgin like water through a tube, or they deny he’s created at all – claiming he’s a figure of light, a chimera. The problem always comes down to the same thing: how can God—the metaphysics—come into the world without contaminating himself in the process? The solution that's found consists of what can be called the sham solution archetype: the idea that Jesus supposedly assumed only a sham body, that what became visible of him was a mere shadow, a mere phantasm. He appeared to the disciples, preached and worked miracles, was indeed in the world – but only as an apparition, and thus immune from any confusion with the flesh and from any venereal disease: a truly Alien God. Theologically called Docetism, from the Greek dokein for ›to appear,‹ this somewhat difficult position is perfectly consistent, given the split between hyle and pneuma. And, logically, Marcion—to whom this doctrine is owed—must deny those nervous points running counter to theological hygiene which, significantly, take the shape of the Cross: the birth and the crucifixion of Jesus. The birth because it would have unthinkably allowed God and man to become mixed in with each other – and the crucifixion because it would have proved this God was mortal. To avoid this, an apocryphal writing rewrites the crucifixion. Accordingly, in this apocryphal teaching, Jesus appeared to his disciple John—who'd secluded himself so as not to witness his master’s crucifixion—in a different place where he laughingly announced that the one hanging up there on the cross was someone else, that the crucifixion was only an evil illusion – and that he, Jesus, was alive and immortal. In short, the Gnostic position is characterized by the denial of the Cross.

Seen in this light, the impulse that introduces this dogma was to valorize the human being. And because no one could think of anything else, they began portraying Mary as an Angel. There are also some grounds for this because suspicions were circulating that Mary had made it all up, that she'd run away from Joseph and conceived a child at night with a soldier named Panthera, to name just one of the rumors. Moreover, the scriptures are by no means unambiguous. They recall the saying, »Woman, what have I to do with you? « or the beginning of the Gospel of Matthew, where the genealogy of Jesus leads through Joseph as if he were a natural son. Precisely because of these dark spots, there is a tendency to make Mary an Angel.

An apocryphal writing from the 2nd century attributes a legend to Mary. She is the child of a priest, Jochim, and at the age of three, she's given to the temple, fed by angels, and kept utterly pure. Pure as snow, she arouses admiration like that of a thirty-year-old. She prays fervently and weaves the temple curtain with other virgins. When she is 12 years old, the widowers are summoned to bless their rods—don't ask me what that means—and a dove flies onto Joseph's rod, which is a sign that he, an older gentleman, is to become the guardian of her virginity – and so it goes on. The problem this legend is supposed to answer is this: Mary is supposed to be as pure as snow, and she's not supposed to contaminate God. This is where the inventiveness of theologians comes into play. The solution is the so-called logos theology. Since it is the Logos, the Word, that becomes flesh, they reasoned, it must be an insemination through the ear. So we now have a virgin birth. The theologian Origen takes this idea further and says that, just as it went into the ear, it must have come out of the other, giving us a virgin after Jesus’ birth.

Starting from this foundation, it is an obvious conclusion that Mary's virginity extended to her entire life on earth. One obstacle on this path is that Jesus' siblings are mentioned in the scriptures, so it can be assumed that Mary must have fathered other children with Joseph after the supernatural conception of the Son of Man. This is, of course, absurd because now, after all the trouble, we'd be dealing with a fallen virgin. So the theologians hastened to explain this blemish out of the world by having these brothers and sisters come from an earlier marriage of the widower Joseph. Through this artifice, Mary has become the perpetual virgin (in partu and post-partum). The step to Mary Theotokos, the god-bearer, is evident from here.

So, we have the archetype of the Cinderella story. Coming from a dubious background, ennobled in several steps and made into the eternal virgin, Mary advances to become the mediator and finally the accomplice in the divine plan of salvation. The God-bearer becomes the Mother of God. And, of course, she, like her Son, is granted the privilege of ascending to heaven and residing there in the flesh, in a virginal form, at the side of the Father and the Son: as the Holy Family.

It is clear: this body isn’t an individual body but a symbolic one, a body free from nature. Mary: As the archetype of the body that's left its natural place, it’s literally u-topical. But the u-topical—a particular dialectic—becomes topical after all. This body, in turn, gives birth to other bodies aligning themselves with it: in the beginning, monks go into the desert, then the monastic brotherhoods, and finally the church itself – and then the material body of the cathedral, which isn't coincidentally named Notre Dame, Our Dear Lady. This brings us to the final phase of this dogmatic architecture, which coincides with the Gothic cathedral for a reason. However pure Mary's life may have been, the last open question is whether she’s still part of the human race – if she’s affected by original sin? According to St. Augustine, original sin consists of libido and evil desire. For Mary to be freed from this, the case is constructed that God supposedly intervened in Joachim and Anna's love life and, when Mary was conceived, provided them with the gift of divine apatheia, a divine lack of lust.

And with the 12th century, the history of the dogma is complete – and nothing more is added. Recapitulating, we could say this process represents a movement toward stellerization movement. This is also reflected in the etymology added to the name. From mirjam, the bitter sea, it becomes stella maris, the Star of the Sea, which steers the church - with the Pope as captain - safely through the perils of time. As you can see, we're dealing with a clear shift. Take the Cathedrals as an exemplar, representing the Corpus mysticum of Mary. Considering that every stone in these buildings has already been schematized, you can see the idea that this body is no longer mystical but technical. It's no coincidence that Modern-day corporate bodies arise from the Cathedral, the Guilds, and, above all, the University. If I were to describe the shift articulated in all of this, I'd say that the body of knowledge is changing its form. It's becoming abstract and rational, as abstract and rational as a wheelwork automaton [Räderwerkautomat].

I don't want to bother you with all my questions about the fine mechanics, but rather, I want to tackle the problem where the Christian God also reveals himself, namely in Scripture. So, let's turn to the form in which the Mechano-Logos reveals itself: the mechanization of writing. We're now changing gears and entering the printing world. Two things are essential for the mechanization of Scripture. The first, which I will only touch on briefly here, is the condition of possibility: that it’s possible to print black on white, that there is, in other words, suitable virgin white paper.

This is precisely where the Gothic paper mills deserve credit. The rags are the medieval raw material, making a functioning textile industry prerequisite – the Medieval Industrial Revolution. Mill technology, textile industry, division of labor. This is precisely what the collective text incorporated into the paper: the abbreviation of the watermark, the producer's logo. The paper should be pure, white, and smooth. How is this done? First, light-colored rags are taken to caves, rotting and turning into pulp. And this raw material must be cleaned, which is only possible where the water is very clear and pure and hasn't yet been contaminated by the tanners who polluted the rivers of the Middle Ages. Consequently, papermills are located near mountain rivers, upstream from the cities. The cleaned pulp is now scooped, flattened, and sized. This refinement process can be seen as a metaphor for the purification also articulated in the history of dogma. It's no coincidence that the mechanization of paper mills coincides with intellectuals' Marian mysticism. Just as the latter is concerned with Mary and the speculum sine macula, the »immaculate mirror,« paper production is concerned with the smooth, empty surface—with the construction of mere receptivity.

Now I, after having bothered you for so long with the Madonna – and, what's more, from the perspective of a Protestant who neither fully suffered nor understood Marian devotion – will take a little leap and come to that Madonna who, for example, sang like a virgin, in a white corset, in bed, lasciviously lolling in front of the camera. There are some strange overlaps here. An Art Historian who organizes small tours through museums told me that if she had the misfortune of guiding school classes through the museum, she always had to deal with this problem. When they come to a painting of the Madonna - and she says, ›Here we have the Madonna in front of us‹, each time she is confronted with a lot of perplexed children's faces - and of course, she is somewhat irritated, in the sense of wondering: ›Did I say something naughty? Has a flatus slipped out of my mouth?‹ Until a child's heart opened up and complained that this woman doesn't look like the Madonna at all, that it's a complete mystery to her how these oil paintings were painted 200 years ago, and watching it all on video is much cooler. I won't hide that the Art Historian told me this as proof that the West must have really and irretrievably perished— who knows whether it really happened that way. For my part, I think Madonna's name choice is anything but coincidental; in her pseudonym, this Detroit lady has precisely tapped into a culturally charged battery. For in Madonna’s speculum sine macula, we can discern a kind of Occidental mirror stage – and we must give her contemporary re-revenant credit for having grasped Madonna's diva structure. In this light, I wouldn't speak of the West's decline but of Catholicism finally being lived out. I'm not even sure whether Madonna is really what is commonly referred to—using an obscure term— as a sex symbol. Because what Madonna presents to us seems to me isn't actually sexual but falls into that register Plato aptly called the device’s gender – which, transposed into today's world, I’d call a sex machine.

And that's precisely what we get to see: pure, clean, serial sex.

If you like, it's nothing more than asceticism, only inverted. But its price says: bodybuilding, work, work it out. What seems much more interesting to me is what lies behind it as a new, inward-looking, psychogenic kind of virginity that's being articulated. And so Madonna is right to call herself Madonna. The innocence that Madonna presents to us lies in the fact that she can shed one skin after the other—I almost said virgin skin. Still, in all these transformations, she retains her ability to negotiate her receptivity. Her body functions like a palimpsest or the video screen that creates and destroys the image; it is the foil of pure receptivity.

Assuming that Madonna is the closest to divinization in the present day we can get, we have to ask what price this media staging comes at. What Angel Maker is behind this strange angel? At this point, Madonna reveals herself to be a true Catholic. Because—and this is undoubtedly the most interesting part—we learn nothing about that. We see the symbol and what it may promise, but not what kind of threat it raises above. This is one reason I left Madonna as a source for the question.

Perhaps my thesis will become more plausible if I describe the sequence of events that led me to the question of hysteria. My original interest was understanding why machines act as phantasmatic magnets, why they are burdened with all kinds of proofs of God's existence, or why they are loaded with metaphysical contraband. I increasingly realized that machines—like the Alphabet—must be understood as symbolic reproduction machines or, more clearly, as birthing machines. Correspondingly, Mechané's foundation is concurrent with the foundation of hysteria. Hysteria – originally meant the womb, or a wild animal, as Plato says, burning with the desire for children but—unsatisfied in this desire—goes to the head. This is where hysteria begins.

Equipped with this argument, it won't be difficult to discover a similar structure in the machine: one is inclined to posit a second-order reproductive machinery in the place of nature. Here, we speak of second nature, artificial life, and so on, and it's in the nature of the great symbolic Machines—Alphabetic Wheel [Typenrad], Wheelwork Automaton, and Computer—to produce a mental surplus having no model in nature – and in this sense, they have a genuinely hysterical effect. Take the concept of identity, for example. It only makes sense on the basis of the formula A = A—but the affinity between machine mania and hysteria goes even further. Just as hysteria doesn't know what it's talking about – but it does so in a displaced, mute way—so the discourse of the Machine doesn't usually know what it's talking about either. It's no coincidence that the great symbolic Machines are shrouded in a kind of twilight zone and traumatic silence. We don't know who invented the Alphabet or the Wheelwork—or also the Computer, born in an era obsessed with a history following every contribution, however marginal, with the zeal of a preservationist, that’s genealogically eclipsed.

The reason for this belated eclipse is easy to see and was already given—and in an exemplary fashion—in Socrates' defense. You can't pass off the letters as a divine language if they refer to something of this world – the chest and the phallus. And so, for the sake of metaphysical flights of fancy, it takes a truly fundamental act of forgetting. However, this forgetting goes hand in hand with a further mistake. Suddenly, the language of the Wheelwork is being passed off as our genetic code, as the language of nature itself, or it's claimed this genetic code, that our brain is a kind of physiological computer. All these renaturalization efforts have in common that they feign nature, where we're dealing with a human artifact. And not only that. They're repeating the grandiose topsy-turvy movement set in motion by Gregory of Nazianzus, a 4th-century theologian, who said: »Virginity is what marriage merely signifies.« This meant that pure love, the love of God—and reason and science, I might add—is the original, while the lower world with its carnal desires is only the symptom, the distorted, derived form. With this trick of thought, Descartes passed off living beings as natural automatons, which today we can read everywhere: that we are information-processing thermodynamic machines.

It's true that the language spoken by our high-flyers and celestial experts today is no longer the lettered writing of classical metaphysics but digital logic, and they no longer speak of the divine but of nature – but the structure of error and misappropriation is the same. For when it comes to the crunch, they always conjure up a concept of nature – only, as Lacan once said so beautifully:

You first have to put a rabbit in your top hat before you can pull it out again.

My formulation of Culture as an Angelmaker opposes this form of illusionism. This formula isn't even meant to be culturally critical. I have no objection to the Angelic. If this formula has any meaning, it forbids returning to a naive conception of nature. It claims it's impermissible to prattle on about the nature of man in one way or another under the sign of the Machine. In the realm of the Machine, which is fueled by the desire to defy nature, we imagine ourselves as angels, as transsexual, extraterrestrial beings. It doesn't matter whether we do or don't do this as individuals – because we are constantly dealing with it, whether we want to or not. If you take any old limited liability company and wonder what kind of strange body it is that's timeless and immortal, and for this reason—unlike the law's so-called natural persons—doesn't pay inheritance tax, you have the proof of the thesis.

The LLC exists only in the image of Christ; it is – like the tax office – his earthly revenant, a transcendent being settled in the real world that now looks like reality. The angels have been among us for a long time, and metaphysical desire has become the lubricant of Capitalism. I have no objection to that. Or if I do, only the small detail is that it’s not in the nature of man to establish LLCs and pay taxes. And so the talk of being HUMAN is a lie owing itself solely to the fact that it obscures the view of the underlying problem: the violated diva, the sister of Caligula, culture as an Angel Maker.

Thank you for your attention.

Translation: Hopkins Stanley & Martin Burckhardt

Burckhardt, M. – Vom Geist der Maschine: Eine Geschichte kultureller Umbrüche, Frankfurt/M, 1999.

Julia Drusilla was known to be Caligula’s favorite sister, and various historical sources have imputed that their relationship was incestuous from a very early age. Indeed, even though she was married to his friend Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, Caligula treated her as if she were his legal wife. Consequently, she’s often referenced as his wife.

Benjamin, W. – On the Concept of History, trans. D. Redmond, 2005. »There has never been a document of culture, which is not simultaneously one of barbarism.«

Die verletzte Diva. Hysterie, Körper, Technik in der Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts [The Wounded Diva: Hysteria, Body, Technique in 20th-Century Art] was an exhibition at the Lenbachhaus in Munich’s Kunstareal between March 4th and May 7th in 2000 with an accompanying text. The event was co-produced with the Kunstverein München, Siemens cultural program, the gallery in the Taxispalais Innsbruck, and the Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden. See Braun, C., Bronfen, E., Eiblmayer, Silvia (eds.) – Die verletzte Diva. Hysterie, Körper, Technik in der Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts, 2000, Oktagon, Köln.

Related Content

The Sleep of the World

After one of his first lectures on the unconscious, Freud made the beautiful observation he’d encountered such emphatic silence from the audience that it was as if he’d stirred the sleep of the world. This formulation describes a social condition where the World’s collective

Alien Logic

The following is the visualization of a lecture Martin gave on May 11, 2021, at Vienna's IWM, where he spent a few months as a fellow in the spring following the publication of the Philosophy of the Machine. Because this lecture is a tour de force pulling together his previous thinking as a prequel to his five-book series, the

I came to Martin from Levinas’ notion of ›the Other‹, and what I quickly learned was this question was so much larger than the question of Gender that my peers were so hung up on. The real question was about ›procreation‹ rather than ›reproduction,‹ and how the Machine introduced the concept of the Neuter, which is the precondition that makes you understand the Gender Role. I’m fascinated by how we talk about »Reproductive Medicine« rather than »Procreative Medicine« as if a birthing machine is simply a Xerox copier…best — Hopkins Stanley

If by Machine you mean as 'Other'ness, then this is very relatable to what I am doing

"My original interest was understanding why machines act as phantasmatic magnets, why they are burdened with all kinds of proofs of God's existence, or why they are loaded with metaphysical contraband. I increasingly realized that machines—like the Alphabet—must be understood as symbolic reproduction machines or, more clearly, as birthing machines. "