Following the English translation of the Labyrinth of the Signs, Parts I & II, as the first installments in a series of chapters from Vom Geist der Maschine, we now post the translation of the seventh chapter, titled Under Current [Unter Strom], which discusses how Abbé Nollet’s experiments with the Leyden jar at the dawn of electricity led to what Martin jokingly calls the ›discovery of the Internet in 1746‹ and the electrification of Writing. Next in the series will be our translation of The Black Sun [Die schwarze Sonne], which examines Sigmund Freud’s discovery of the unconscious—or, more precisely, the strange phenomenon with which Freud created a metaphysical battery that elegantly obscures the conditio sine qua non, namely the electrification of society, leaving the reader with the unsettling realization that we are actually dealing with an unconscious of the unconscious.

Hopkins Stanley

Martin Burckhardt

Under Current

Flashback

The year is 1746, a year marked by few major historical events. In Lima, across the ocean from Europe, the earth quakes and trembles; Frederick V replaces his father, Christian VI, Ferdinand VI replaces Philip V, and in America, the American General Pepperrell is knighted as Sir William. There are wars of succession, intrigue, and romance—nothing new under the sun, as far from the cities, armies stand facing each other, both armed and armored with massive machines of war, fighting out the struggles of dynasties on battlefields that resemble chessboards. At best, anecdotes make the rounds as exemplified by: Lord Hay, who stepped in front of the enemy troops at the Battle of Fontenoy, offered a toast, then challenged them to fire first. In Paris, Rousseau finished his heroic ballet and opera on the »Noble Savage,« which the court appreciated, but was too busy, so all that can be said is: »Time passed, and with it the money.« The year 1746 passes, just like the one before and the one after. Absolutism is at its zenith. But of course, where the Sun of the European court doesn’t shine, something new is beginning as Rococo ornamentations are transforming into lines of sentimentality, shown passionately at first, then with increasing nervousness. What appears to be a daydream of heated imagination, like cirri-form wisps drifting across the sky, will eventually gather into a storm cloud that finally sweeps across the landscape as revolutionary fervor. But that’s still a long way off for now. When new ideas emerge, they do so only in isolated forms. In Königsberg, the father of the young philosophy and theology student Immanuel Kant dies. Meanwhile, Samuel Johnson compiles an English dictionary of unprecedented scope, Diderot begins work on his Encyclopédie, and a series of memos are published that later will mark the Age of Enlightenment‛s agenda. You could think of the year 1746 as the midday of Absolutism, that state of stagnation in which change itself seems like a daydream. »The sun shone, having no alternative, on the nothing new.« (Beckett1).

But this impression of uneventfulness is also misleading. The year 1746 brought a shocking experience with it—one more powerful and, above all, more enduring than the precipitously fleeting fantasies of the French Revolution of 1789,2 which marked the beginning of Modernity. The standards of thought shifted so fundamentally here that we must speak of a revolution in thinking. Naturally, this change didn’t immediately write itself into history, nor did it have a clear historical agent. What changed was the episteme, the field of knowledge.

The Field of Knowledge

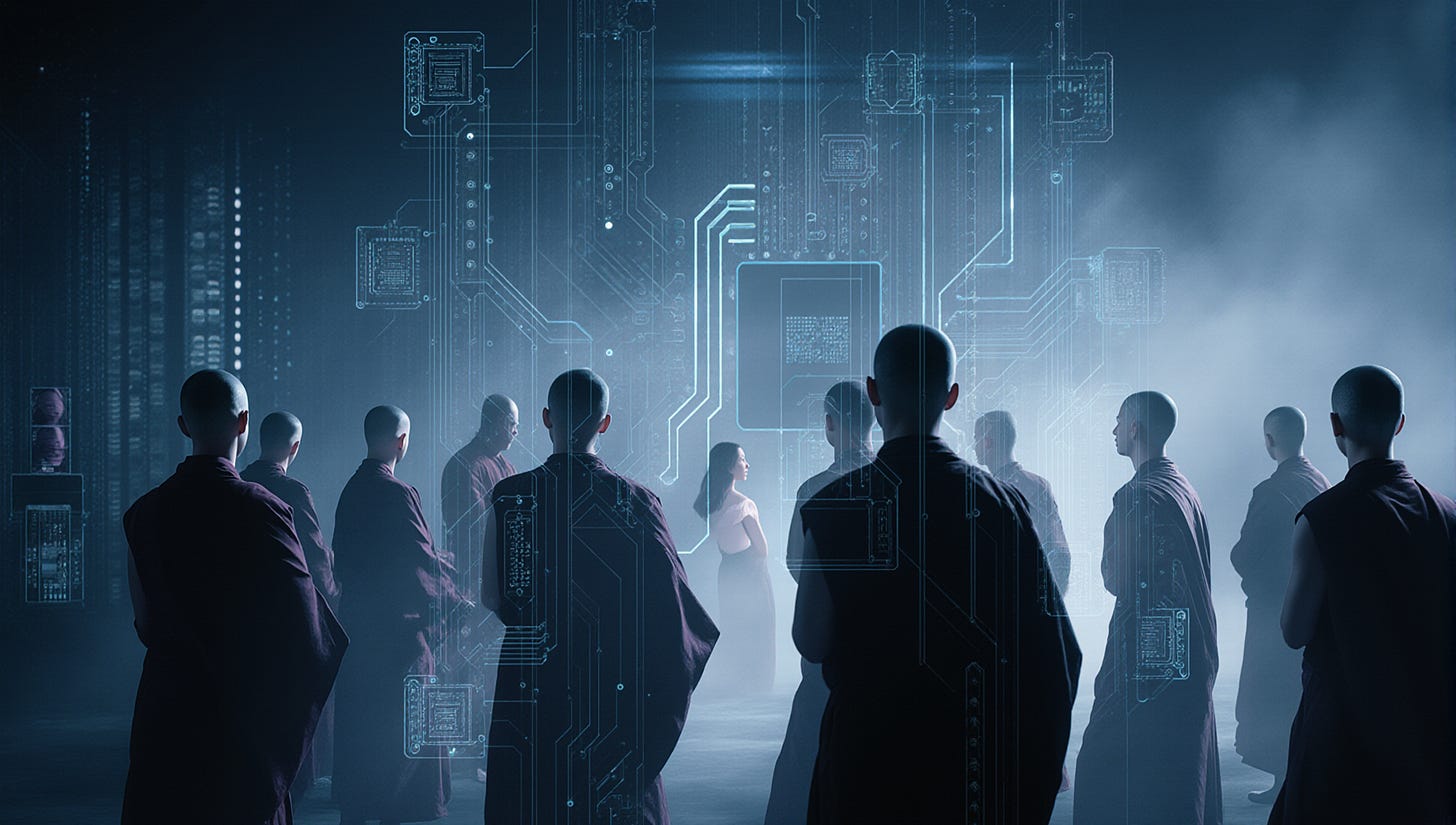

Remarkably, the field of knowledge isn’t just an abstract intellectual space but a real place somewhere in northern France. In my imagination, it resembles one of those flat green military cemeteries you find in Normandy, just without the crosses. An abbot, Abbé Nollet, stands there, instructing 200 Carthusian monks to form a circle. The circle is enormous, several hundred meters across, but the monks can still see each other. Once everyone is in position, the monks start wiring themselves together with iron wire. When this is finished, the abbot touches a container wrapped in tin foil, both inside and outside, filled with water. A small wire resembling a homemade antenna extends into the container. At the moment the abbot touches the container, something strange occurs—a phenomenon that deserves to be called a temporal rift [Zeitriß3]—the wire-bound Carthusian monks all begin twitching at the same time.

Now, this act isn’t some obscure ritual, but a highly scientific experiment dating back to electricity‛s early days, when, just one year earlier, it became possible to store a large charge of electrical current [Strom] in a capacitor: the so-called Leyden jar.4 This is precisely the news reported by Herr Musschenbroek in a letter dated January 1746. »I am sending you details of a new, truly terrifying experiment, and advise you not to repeat it yourself.«5 Thus, the storage of electricity, which remained an inexplicable mystery well into the 18th century, marked a profound turning point in the history of electricity.6 Equipped with such apparatus, the effects of electricity—previously difficult to extract from matter—could now be systematically investigated. It’s in this sense that Abbé Nollet, a highly respected physicist and experimenter, approached his work in a thoroughly systematic way: he electrified mustard seeds to see if they germinated faster, electrified dead birds, and at Easter, the festival of resurrection, he attempted to treat a paralytic patient—with the result that one of the patients »felt a tingling sensation in an arm that had been paralyzed for several years, which he had never experienced before and which made him want to be electrified again.«7 The electricity that Nollet’s teacher, Cisternay du Fay, had described just a few years earlier as a »minor phenomenon of physics« is now revealing itself as an unprecedented force. Nollet, meticulous as he is effective in his experiments—earning him the task of teaching the royal family the secrets of electricity—demonstrates this power before the king. At the king’s request, he arranges 180 soldiers in a circle, has them join hands, and, with a single discharge from his apparatus, causes them to jump into the air. In the monk’s version of this experiment, the question was figuring out how quickly this strange substance traveled through space—a question that, back when electricity was still largely seen as mysteriously occult (with thinkers like Kant pondering if cats had some sort of special animal electricity), truly needed answering. And the answers arrived so swiftly that they scrambled all the old ways of thinking because electricity moves so fast that you cannot see it with your eyes, which seemed to mean it moved without any time passing.

Episteme

We will now focus on this field because it has the characteristics of an epistemological field, a field of knowledge.8 In this sense, it isn’t just about a specific experiment from the early days of electricity, but also about the ideas that emerged from it—ideas that went far beyond what the people involved could have imagined or thought possible. »When the scale changes,« Emile Durkheim profoundly observed, »the nature of human relationships and institutions also changes.«9 This sentence offers a thorough critique of what is considered »history« and what constitutes a historical act. The actions of the actors are not purely autonomous but are embedded in a web of thought patterns and time scales that are so transparently obvious to the actors that they don’t consciously recognize them as factors influencing their actions and society. Seen in this light, scale can be understood as the historical driving force [Triebkraft] par excellence.10 Nevertheless, scale also has a historical dimension because the structures of space and time that span historical periods are themselves historical artifacts: Space-Time-Machines. The historicity of this scale is obscured to the extent that it (like the time of the Mechanical Clock) is taken for granted, assumed to be natural.

At this point, Durkheim’s statement about the Nature of human relationships and institutions is strangely imprecise, even absurd. Magmafied down to its core, it argues that Nature arises from standards. This puts him precisely in line with Descartes’s instrumental error, who sought to breathe nature into the Mechanical Clock and concluded from the Wheelwork Automaton [Räderwerkautomaten] that Natural automata existed. Insofar as human relationships and institutions are traced back to an a prior standard, it is hardly possible to speak of human nature anymore; au contraire, it would be more accurate to see this so-called >Nature< as a symptom of abstract, culturally grown forms. This raises the question of the historical agent, the cultural driving force that recodes the nature of human relationships and institutions as defined by their constitution. In this context, it‛s notable that the Revolution of 1746 didn‛t go down in the annals of history as a date steeped in history, but appears rather as a confused waking dream, a construct still belonging to the night sky of thought—this is why, when we speak of a revolution, we should speak of a Revolution without Revolutionaries. In a sense, the history of changes in standards is the history of forgotten, obscured revolutions.

The core question underlying Abbé Nollet’s experiment is one of time. How quickly does electricity travel? The answer is: electricity moves so fast that we cannot notice any passage of time. Everything in this circle happens simultaneously; there is no detectable time difference between points A and B in space. This dispenses with the conventional Arrow of Time,11 inaugurating what is known as real time—which essentially marks the spatialization of temporal processes. Time no longer forms a line but a circle. From there, it is only a small step to a bizarre claim: the Internet has its roots in the 18th century. Because what the Techno-Monks, twitching in real time in a circle, are demonstrating is precisely what we call a processor (which would make them, curiously, Human Processors). While this may sound strange, it is entirely accurate. The central processing unit (CPU) of a computer is characterized by its ability to represent a self-oscillating space, a space where data waiting to be processed is made available in real-time. In other words, there is no time difference between points in space; everything is equally distant. This is the condition of possibility for real-time and virtual space to both co-exist.

If we now consider what is new about this processor, it lies precisely in its ability to overcome the time lag in space: the time it takes to transport a charge from A to B. In this sense, the processor achieves what could be called the Removal of the World. From the perspective of this space, where the speed of electricity has eliminated the familiar distances, the scale of what we call »virtuality« would need to shift—after all, this space is as real as an electrical surge [Stromstoß], and the feeling of unreality comes from stepping into an unreal space that our bodies cannot handle. A Sign Body fed into this space is comparable to one of those medieval angels believed to be moving so fast that if caught in a rain shower between Barcelona and Rome, hardly three drops of rain would fall on them. Seen this way, it is not only picturesque but also perfectly fitting that monks, of all people, subjected themselves to the practice of collective electrification. They formed a claustrum of a new order, a paradisiacal world where everything is within reach, as in the land of milk and honey. Since then, processors have become smaller and thinner every year, eliminating the need for cables and human resistance – yet the goal has remained the same. When you enter a monastery, you leave your old worldly body outside its walls. The monastery isn’t just a gateway to a new World, but it also blocks off another. This same feeling of closure also applies to the telematic space of electricity: For this processor, space conflicts with the inertia of the human body, with the fact that we are not equal to the ideal of omnipresence. As a result, Internet pilots must park their sluggish bodies, often called wetware, in a chair before embarking on their journey.

The question remains: why do we need to look back to the 18th century to understand the origins of the Internet? The answer is very simple: the »Human Processor« described by Abbé Nollet demonstrates how what we now metaphorically12 call a network has a real foundation. This avoids the false distinction of separating virtual space as something artificial from what‛s considered reality. It is precisely the physical aspect of the wired, electrified monks that shows us the Internet is part of a networking tradition, not a break from Modernity, but the ultimate logical expression of our electrical modern collective. Social networking is Modernity’s human condition. And as Abbé Nollet’s experiment shows, it not only makes the monks feel comforted in a sense of a collective community they’ve never experienced before, but that it also comes at a cost – because disconnecting from the twitching collective to live your own life isn’t easy. Unplugged.

Mass(ification)

Insofar as electricity transforms the bodies of the wired monks into a twitching, synchronized »mass,« it can be described as the first true mass medium. Although the concept of mass may sound strangely foreign in this specific context, it isn‛t immediately transferable [übertragen] to the figurative meaning — the phenomenon studied since the late 19th century as mass psychology. While the mass psychological perspective risks becoming quickly entangled in the timeless aspects of anthropology,13 the wired monks of Abbé Nollet evoke a historically and psychophysically accurate image—here, for the first time, a pile of bodies wired together reveals itself as a whole, just as the soldiers shockingly leaping into the air embody a new form of field strength. Naturally, anticipating an objection, the printing press of the 15th century, when about a million books were already circulating throughout Europe, could also be called a mass medium. However, the massiveness lies in the book itself, not in the reader who always engages with the text individually. In contrast, the twitching bodies of the monks form a new kind of massification, as they are interconnected in the blink-of-an-eye in a way that creates a collective entity. This entity can become aware of its own mass-like nature through a feedback mechanism. In this sense, electricity represents the medium that creates a mass in the modern sense.

The clarity of the image's physical form shows that a term like collective body isn't just a social construct. It specifically refers to the psychophysics of the mass marking a historical dividing line: this collective entity, which reacts in real time and shares the same sensation, represents a historical formation without precedent14 – and is based on electricity as its condition of possibility. Seen from this perspective, it is highly questionable whether the concept of the masses possesses the necessary precision to differentiate between traditional mass gatherings (such as those in the church and the army) and the electrified masses. In fact, the modern masses no longer need to gather physically; it is enough for them (the silent majority) to work themselves into a frenzy through the power outlet, in other words, in a transferred form which unites the individual into a twitching whole. Childhood memory: what it was like when walking down a deserted street, seeing the bluish glow of televisions behind curtains, and then hearing that cry coming from everywhere and yet as if from a single throat—Goal! In this sense, the psychophysical incarnation of electrical mass corresponds to a movement toward abstraction: toward an invisible but no less real entity.

Undoubtedly, Abbé Nollet’s attempt highlights a somewhat obscure area that has slipped into a twilight zone of consciousness within the theories of the masses, as presented by Le Bon, Freud, Canetti, and Broch. Reading Freud’s Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego, we can see he bases his concept of the masses on the Mind of the Father – that he sees projection mechanisms at work in the artificial masses of the Church and the Army, which follow a Father substitute in the form of a spiritual or secular leader. Now, it isn’t without irony that Abbé Nollet uses these two historic mass formations in his demonstrations, proving the soldiers’ strength in one swift display—just as he manages to bring his Carthusians, it must be said, to a state of ecstasy. In doing so, however, he powerfully demonstrates that crowds of people no longer need a figurehead to form a mass. When bodies are welded together into a mass, they are no longer held together by some idol or representative; they are not even bonded through the Sign of Something, but rather they are directly connected. But no, »immediacy« is fundamentally wrong here, because there is a medium: electricity.15

Truly, it is a recoding of the first order. For now, it is a non-personal agent assuming the Father‛s role—or rather making that role unnecessary. Perhaps it‛s no coincidence that, once they understand themselves in this way, the masses quickly rid themselves of their king to focus on highly metaphorical constructs: the Supreme Being and the Nation. In this sense, you could say that the King and the Executioner had already died long before the turmoil of the French Revolution.16 In a world where one-is-in-the-other and everyone is connected to the collective battery of the masses, they inevitably become foreign bodies. And perhaps this is what the French revolutionaries were truly celebrating when they inaugurated the Festival of the Supreme Being: not Man, but the battery that gives him the sensation of being-one-with-another. Liberté. Egalité. Fraternité. In this context, it seems rather pointless to invoke a historically powerful, autonomous subject. It is astonishing that Freud also completely overlooks the electrified masses, instead fixating on the Father and Oedipus figures—just as nearly all authors who have studied this phenomenon have overlooked the semantics of electricity. In Freud’s case, however, this fact is even more remarkable because the psychical apparatus with which he attacks the phenomenon cannot deny its roots in electromagnetism—a point that will be discussed later.

In Formation

What are the semantics of electricity? While this question may seem strange, it becomes less strange when considering that electricity is the telematic battery par excellence—and insofar, it has a close connection to the modern conception of information. If it was previously said that the speed of electricity determines the distance within the world, then it’s clear that this omnipresent hero embodies the ideals of all the telematic devices characterizing Modernity. It is, therefore, all the more surprising how conspicuously electricity‛s absence is in the definition of information. We are, according to Shannon’s definition, dealing with a sender, a channel, a receiver, and a charge, which is simply described as needing to be encoded during transmission and decoded upon reception. However, the medium enabling this transference in the first place—and which once seemed like a miraculous substance in the 18th and 19th centuries17—has now been completely removed from the equation. This absence is even more surprising considering how this conception of information completely replaces the traditional understanding of Writing, especially in the context of a procedural description of a transmissive transference technology [Übertragungszusammenhang].

Taking this absence positively, what is the benefit of its sleight of hand? In short, you can sidestep the semantics of electricity by creating a syntax without one. Information becomes a meta-script, a Sign no longer needing to be embodied. The similarity to the Alphabet is striking. Just as the doctrine of the alphabetic purity of the Sign is only a reflection of a metaphysical belief, Shannon’s idea of information also seems to be the rational side of a strange, even completely irrational desire—a desire that is articulated in its meta-biological form. If information is understood as vis vitalis, meaning as life force, then the path to the fertility sign isn’t far off. Just as the Alphabet excludes the Body of the Ox, and just as this exclusion enables us to engage in Natural Philosophy, so the subsequent obscuring of semantics allows evolutionary theorists to speak of Natural Programs, Autopoietic Systems, and the like.18 However, if instead of starting with Shannon, I derive the concept of information from Abbé Nollet’s monks, it’s because how they come into formation is fundamentally a type of information: information about information.

On this side of a meta-theory, the interest lies in tracing the hidden meta within the common concept of information back to its original form, where its initial claims can be recognized. So when we talk about wanting to expand the field of knowledge to include an interest in knowledge, this isn’t mere sophistry, but has a very physical dimension: the monks whom Abbé Nollet trained in this field are interested in the most immediate, literally in-between [dazwischen]—between iron wire and battery. Therein lies this image’s advantage: it makes visible again all those processes that have inexplicably disappeared from view in Shannon’s apparatus. Abbé Nollet’s experiment shows that what is transmitted is not random, but that the meaning of electricity is always transmitted in this context of transmission. Therefore, Pure Information is just as questionable as the Pure Sign is metaphysically charged. Seen in this light, the experiment’s context becomes more than just significant; it becomes crucial. Abbé Nollet’s question doesn’t just touch on a minor detail, but rather delves into the very core of the epistemological field itself, explicitly addressing the questions of Time and Space. It is about nothing less than the a priori assumptions of Modernity. That this a priori structure has been overlooked or forgotten in our understanding of »information« shows just how much we are likely to be dealing with a fundamental oversight.

Transmission/Transference

If Shannon refers to the term information as purely the technical aspect of a transmissive-transfer, and if—when transferred [übertragen] to what we call »reality«—the figure of a newscaster delivers news of a grotesque world as if it were just pure information, then the question arises about what kind of »transference« we are dealing with. Based on what has already been said, the word‛s double meaning is unmistakable: »transference« is also a psychoanalytical term. In this sense of transference, the image of the Father is transferred to the Analyst—which can be understood as a projection of the second order.19 While we’ve previously discussed the Representational Projector expressed through the image of the KING, we now see transference of the Father’s mindset to the communication machine. This observation doesn’t quite align with the classic Freudian interpretation20 (as already noted with the issue of mass), but that shouldn’t prevent us from exploring this idea. It is, above all, the contrast between telematic transmission and the representational triangle (King, Collective, and Law) that signifies the deep shift occurring here. While in the triangular representational realm of Central Perspective (where all points in space are depicted and viewed from a single, emphasized point), the context of electrical transmissive-transfer creates a void: the position of the King remains unfilled. However, this means that the collective not only loses its representative (its image), but also that the Logic of Projection and Reflection itself becomes obsolete. This process is further complicated by how what was previously referred to as an Omnibus, in only a symbolic sense, now becomes a reality: that artificially composed, collective body.

In a certain sense, the triangle is redefined on an abstract level. The KING is replaced by the MASS, not as a collection of isolated human bodies, but in such a way that the mass is integrated into the framework of transmissive-transfer as prototypically presented by Abbé Nollet‛s experiment. Here lies the law, the Constitution of Modernity. Insofar, the death of the king doesn’t mark the beginning of lawlessness, but only the moment when the law—the Father’s mindset—becomes abstract.21 With its constitution as a mass entity, the collective loses its transmission apparatus, which has served Europe since the early Middle Ages’ days of the speculum sine macula, as a means of self-assurance. Where the King once sat enthroned, now sits the Representative who talks his way out of the system’s constraints; where the King’s potency guaranteed sovereignty, now stands an electric chair.22 If, as the martial rhetoric of modern totalitarianism suggests, the Nation is welded together, then this bond isn’t really made of blood, sweat, and tears, but instead resembles the pattern of wired monks, creating a collective echo chamber reverberating within itself. Attributing atavistic instincts to the Nation or Nationalism fails to take into account the complexity and, more importantly, the historicity of this construct, much like Freud’s mass psychology, which evokes the image of the primal horde and assumes that »the psychology of the masses is the oldest form of human psychology«.23 That twitching, collective body is what is first created in the bodies. The Law of Representation gives way to the Law of Simulation – and this law, in turn, is deeply linked to the semantics of electricity.

However, it should first be noted that this transfer of power takes place not in the usual manner (The King is Dead, long live the King!). Rather, we are facing a standstill, a breakdown. It is no coincidence that mirror‛s loss brings with it a dilemma that the story‛s characters try to avoid, whether by placing themselves (like Mirabeau) in the absurd position of royalist revolutionaries, or by devising a kind of god Machine, a supreme intelligence that understands all human passions but isn’t subject to them, or like Robespierre, establishing an être suprême, a kind of State godhead that promises elevation to the virtuous – and to which wickedness can be sacrificed. All these acts are characterized by attempting to fill the empty space with a higher being, a spiritual battery. However, it is evident that they cannot align with the mind of the Father who now reigns in the context of transmission.24 At this point, we might once again ask about the connection between the problem of Writing and the Masses. As already mentioned, the collective is deeply linked to the aspect of the legein; it follows the pattern of Writing and thus of communal reading. Against this background, the question arises once again as to what the semantics of electricity really mean.

Neon Sign

There is a notable disconnection between discussions about the semantics of electricity and the traditional understanding of »semantics«. And if we follow the linguistic rules of academic purism, such an expression borders on nonsense – after all, this places the electric shock on the same heuristic level as the World of Words. But compared to a word, an electric shock is at best a semantic void. It’s equally doubtful whether the monks’ convulsions can be seen as meaningful and intentional Speech Acts, or if we’re even dealing with language and meaning here. Armed with these objections, you could dismiss the semantics of electricity as an inappropriate concept, while, of course, a second glance reveals the meaning of this supposed nonsense. This is because the electric shock sending the Carthusian monks into convulsions is merely a symbolic foreshadowing of how Modernity communicates and transmits information, where electricity plays the role of a conditio sine qua non— making it all the more remarkable that electricity is always assumed but never questioned. Just as Shannon’s definition of information doesn‛t focus on the messenger carrying the encoded message from the sender to the receiver, the dichotomy between signifier and signified doesn’t fully capture the meaning of the transmissive substance of transference.25 Now, based on the course of our current investigation, this situation is no longer very surprising, but rather represents the repetition of a drama that has been tried and tested many times over. Just as the bull was displaced from the Alpha Sign to be reborn in a tamed form as Natural Philosophy—so too is the material carrier substance removed from the Sign’s conception so that it can be reinvented as a malleable figure of thought (such as an autopoietic system or similar). If this mechanism of escamotage functions by creating a kind of contact barrier between the signifier and its material carrier, then electricity can be seen as this law‛s exemplification, since its use is based precisely on the signifier being »insulated« from the circuit. Furthermore, if the image of the monks wired together – similar to other experiments from the early days of electricity – is enlightening, it is primarily due to their lack of insulation.

However, once you conclude that every transfer of meaning [Sinnübertragung] can only happen through a carrier of meaning [Bedeutungsträger], this logically leads to a decisive reevaluation of the carrier of meaning. In this sense, it is the emergence and coming into effect of a new transmission substance, in other words: this shift in transmission modality, represents a drastic cultural change impacting all aspects of the transmission process that adds a myriad of new modes of transmission. So if, despite linguistic objections, there is talk of a semantics of electricity, it’s because this messenger substance recodes the entire modern context of information transmission. Just as the mechanization of letters was accompanied by a revolution in the Medieval conception of Signs and Writing, the electrification of monks had far-reaching consequences not only at the level of the wired masses (the collegium), but also recoded the register of Writing itself. Therefore, it’s no coincidence that J. H. Winkler, one of the early pioneers of electricity, delighted his visitors by demonstrating a neon sign to them:

›The more strongly a metal is electrified, the more vividly the light in an airless glass tube glows when one approaches it with the same metal. Place letters in front of such a tube: they will glow brightly when the tube is brought close to a strongly electrified metal in a darkened room.(...) Some distinguished persons to whom I had the honor of showing the electrical experiments were particularly delighted when they saw the initial letters of the most illustrious name AUGUSTUS REX illuminated in the brightest light in the open air and in a room where everything was dark, saw them appear to burn and observed the surging flood with which the electric light suddenly permeated and filled the glass letters.‹26

What does the advent of illuminated Neon Writing [Leuchtschrift] mean? The sensation caused by J. H. Winkler’s fleeting letters can be understood as a process of ›illumination,‹ as the moment when Writing transitions into light. From now on, the letter no longer stands as printed, but rather as if illuminated; this is an ephemeral manifestation, a phainomenon, a display. Whereas the phantasm of Writing was directed toward the immutable law, toward the metaphysical World Formula enthroned like a fixed star in the sky of thought, logic now takes its place with its ability to appear, disappear, and reappear. Structurally speaking, a temporal dimension now enters into the Sign, or to use a technical term: a time code. While the printed type, imprinted in black ink on white paper, asserts a kind of logic of perpetuation or at least basks in the reflection of a metaphysical nunc stans, the flickering writing on the display has a mercurial quality that, as a pulsating, metamorphic entity, is capable of changing volume and form.27 Attempting to grasp this transformation of Writing more broadly, we could say the structure of time, as that artificial eternity conceived by thought, is being transformed. The logic of perpetuation (metaphysics) is replaced by the logic of development (metabiology). From a religious perspective, the suddenness of the illuminated writing corresponds to the epiphany, while the immateriality of the written Sign (the pure light) is evidence of its spirituality. Of course, this is brought about by a technical apparatus—it is not a god but an electric dynamo that sustains the energized, disembodied Sign.28

The dissemination of the written word not only brings with it a fundamental change in the traditional concept of writing, but also allows what can be considered writing to become more diffuse. One of the most intriguing questions in the field of electromagnetic Writing is: What kind of Signs does this Writing actually consist? Even a quick glance at a computer screen is enough to make you recoil from the boundlessness of this question. Images, sounds, texts, formulas, program instructions, compression and decompression algorithms, written in various formats, dialects, and so on—all of this may seem like a multimedia library of Babel. Nevertheless, we should attempt to ask this question. Perhaps it best takes shape when viewed against the backdrop of the electrified monks. Let’s put ourselves in their position, in the blink-of-an-eye, before Abbé Nollet touches his capacitor. If you had asked an educated person in the 18th century what a Sign was, they would probably have first mentioned numbers and letters (reflecting medieval thinking). Then they might have mentioned musical symbols. Next, they would likely have considered hand signals and gestures of daily life, pictorial signs, artistic and religious symbols, and finally specific pre-existing meanings in Nature—spots, marks, or physical symptoms. – If the question had been clarified to mean that only something reproducible, clearly defined, and intersubjective can be considered a Sign, then not much would have remained beyond alphanumeric code. You might call this the intellectualism of pre-digital logic. Or, to put it in biblical terms: the mind hovering over the waters. However, the difference between Mind and World becomes obsolete with the electrification of the Sign. For insofar as the logical form enters the body, the mind is in turn liquidated. We can therefore tentatively claim that anything that can be electrified can become a Sign. However, this would greatly expand the concept of the Sign, as it would now encompass the entire World. With the semiotization of the World, the old, clear-cut division between the beyond of logical forms and the here and now of bodies (between hyle and pneuma) becomes blurred. The abstract no longer reveals itself as the non-physical, metaphysical (as that which eludes the regime of the physical), but instead inserts itself into the body. And because, conversely, every body can be a carrier of a code, it must be understood not only in its physis, but always also as a coded and linguistic event. Here, as a mass phenomenon, that old Christian dilemma returns: the dualistic nature of Flesh and Word.

From this perspective as well, Winkler’s experiment is extremely interesting. When his illuminated writing appears in an airless tube, it captures these two dimensions of the body, continuing and carrying this ancient division of hyle and pneuma into the here and now. For if we take the body as the carrier of information, then the ideal body is one that is capable of binding information to itself. However, this ideal, non-conductive body is no longer a body, but a vacuum.29 While Galileo Galilei brought the vacuum into play as an investigative tool for guaranteeing the World System’s smooth functioning (»Imagine the air away,« is the request in his Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems30), under the conditions of electricity, it‛s no longer a question of res extensa in a vacuum, but that of the body as nothing.31 In an extreme, unsurpassable form, this marks the division that characterizes Modernity: the code and the nothingness, Writing and its medium.

Pneuma

It is no coincidence that religious concepts and ideas are intertwined in the description of the historical revolution that electricity represents. The electric shock of the 18th century marks not only a fundamental shift in the epistemological field, but also releases emotional vibrations that are clearly of religious origin. The spiritual battery connected here is that of the Sign of the Cross. To the extent that God becomes Man, Man becomes more like God. In the terms of Hegelian philosophy, this would mean: the abstract becomes concrete, the concrete abstract. The soul of God (or what is believed to be as such) inscribes itself into the World – becoming the World Soul.32 This term, which became a philosophical program in Romantic Natural Philosophy, describes the problem exceedingly precisely in all its dazzling ambiguity: for it is about Transcendence in Immanence. Insofar as it is significant that the great systems of thought in Romantic Natural Philosophy oscillate between Sacred Embrace and »new System Theory«, between religious sensibility and cool rationality. What’s being articulated here is a kind of down-to-earth miracle of Pentecost. The abstract sphere of the Word is given concrete form. Insofar as the evocation of the World Soul (which can be understood as animated matter) marks not only a new chapter in the history of science but also draws on religious traditions.33 It‛s precisely this fundamentally ambivalent dimension that draws on religion to transport the human—and all that is human—into the realm of the divine, providing the intellectual foil against which the early, sometimes playful experiments with electricity must be viewed. One of the early experimenters created a so-called Radiant Crown [Strahlenkrone], which he electrified and used to draw sparks from the head of the female wearer—a process he sensibly baptised Beatification, meaning bliss. The line of thought and the ideographic potential feeding such an experiment are unmistakable. To interpret the Virgin Mary‛s electrification as a mental aberration or, depending on your point of view, as sensationalism would be misleading—in fact, this dip into the past hits the nail on the head. Mary, the pure receptivity that served the 15th century as a form of spiritual precursor to the printing press, becomes a new kind of medium—and in this mediality, the apotheosis of this new and wondrous medium, understood as a life force, as vis vitalis, takes place.

Electricity is a miraculous substance, and those who experience it firsthand witness a transubstantiation. In the mid-18th century, Daniel Bernoulli experimented with reviving drowned birds using electric shocks; Nicolas revived rabbits suffocated with carbon dioxide, and the Danish physician Abildgaard brought a chicken back to life after killing it with an electric shock to the brain by administering another jolt of electricity.34 Therefore, it isn‛t surprising that electricity was regarded as a miraculous substance with thaumaturgical powers. This reverence persisted well into the 19th century. When the first transatlantic telegraph cable was successfully laid in the middle of the century, Messrs. Briggs and Maverick wrote:

»Of all the marvellous achievements of modern science, the Electric Telegraph is transcendently the greatest and most serviceable to mankind. It is a perpetual miracle, which no familiarity can render commonplace. This character it deserves from the nature of the agent employed and the end subserved. For what is the end to be accomplished, but the most spiritual ever possible? Not the modification or transportation of matter, but the transmission of thought. To effect this an agent is employed so subtle in its nature, that it may more properly be called a spiritual than a material force. The mighty power of electricity,- sleeping latent in all forms of matter, in the earth, the air, the water; permeating every part and particle of the universe, carrying creation in its arms, it is yet invisible and too subtle to be analysed. «35

Maverick and Briggs, mind you, who wrote this apotheosis of electricity, were not clergymen, but utilitarian-minded, coolly calculating engineers. And if even people of this ilk could bring themselves to such effusions of heartfelt emotion, it was hardly surprising that a storm of protest arose when, shortly afterwards, the idea was floated of executing criminals sentenced to death by means of electric shocks – for this was seen as a desecration of a »divine substance.«

Against this backdrop, it remains questionable whether mastery of this substance (as embodied in the Leyden jar) can be left to the History of Science, or whether a religious-historical perspective should be adopted instead. From this point on, however, a completely different story would unfold of God’s objective reification, his incorporation into society, and, ultimately, his disappearance into the Laws of Reason. The divine spark, Jupiter’s privilege as the divine thunderer in ancient times, now passes into the here and now. Or more precisely: the problem of this life and the hereafter will be dealt with in another dimension—thus bringing a long development to its conclusion. If we take the individual stages of this progressive transubstantiation miracle, first we have the construction of the Logos in the Alphabet, then its descent into Christianity, followed by its ascension in the Assumption of Mary, then the mechanization and auratization of transcendence in the Logic of Representation, and finally its material incorporation—Formation—Information. Reading along these lines, we can see what a profound change electricity has wrought. The Logos no longer adheres to that pneumatic instance characterized by being not earthly, but intellectual; it no longer functions through the figure of the Representative (or, structurally speaking, through the Central Perspective Triangle, the Law of Representation), but inscribes itself as a physically perceptible sensation in the individual. Conveyed to each individual, this sensation creates what, from a theological point of view, could be called immediacy before God. The distance has been removed; therefore, there is no difference, and the individual, in a sacred embrace, may feel that he is the place where the World Soul pulsates. Thus, the Marian event becomes universalized, rendering the union with God, previously only possible for mystics, as an enthusiastic figment of the imagination, an immediate reality under the conditions of electricity.

When we say that electricity is grounded, we can, considering its historical origins, speak in general terms about the grounding of the Logos. Insofar as the Logos represented the pneumatic, and therefore non-earthly sphere in early Christian thought, we are now dealing with a complete inversion. Seen in this light, it’s questionable whether the religious-historical point of view, as such, is tenable, as this grounding clearly goes hand in hand with neutralization. Just as mechanical philosophers enclose God within the Wheelwork, so too does the grounded, wired, and networked isolated god gradually become less visible in the human world. Basically, we’re dealing less with a god than with an abstract God Machine communicating not through revelation theology, but rather it releases revenant figures in veiled, metamorphic forms. Essentially, it’s a recycling process: the material and its structure are transformed into new and different experiences. In the world of the zapper, the problem of this World and the hereafter, the transcendence of Space and Time, becomes routine: because every this World can appear in an inner-worldly hereafter, just as every inner-worldly hereafter can be projected back into this World.36 With electricity, Modernity enters the artificial paradises of telematic space, the realm of the virtual and remote control.

It‛s all the more surprising that the religiously coded semantics of electricity (which is essentially fueled by philosophical batteries) are barely visible as a trace memory two centuries after its introduction. It has been sublimated to the point where chiliastic hopes are now directed toward »the network« itself, the collective intelligence, and that strange process called globalization.37 There is no doubt that we are dealing not only with new realities but also with highly charged fantasies that share similarities with the World Soul—except that the historical bridge linking them to the 18th century experience has been torn down. Essentially, the media is repeating the mistakes that have characterized the history of Western rationality from its very beginning. The mechanism is notorious. Once again, it's the concept of the medium, once again, it's a misunderstood »Nature« allowing us to overlook the Signs that the medium inscribed in the 18th century. Marshall McLuhan (who otherwise has such a keen sense of the cultural significance of electricity that he speaks of the »Age of Electricity«) writes: »While all previous technology (except language itself) had actually extended part of our body, electricity has brought the central nervous system itself, including the brain, out into the world.«38 In other words, electricity no longer has any semantics, but represents a Natural event [Naturgeschehen]. It’s under these auspices that McLuhan can speak of electricity as the hormone of society, as a messenger substance that functionally informs society about the overall state of the collective organism. Thus, without warning, the wired monks have grown together into an organic collective.

This raises the question of what this magical substance’s incarnation entails, raising further questions about the electricity stored in the Leyden jar. Electricity is an appropriate word, as it helps us understand that we’re dealing with a flux phenomenon, with a medium without boundaries and a consistency similar to water. It places whatever it touches under a current [Strom], immersing the object in this special flowing element. When electrified, the object softens and becomes spongy until it appears to be nothing more than software—a dissipative structure dissolving into the medium itself. (This is actually the original meaning and origin of the word. Software refers to the cryptographic messages used in World War II submarines, which were made water-soluble so that they would not fall into enemy hands if the submarine were sunk.)

If there is one defining characteristic of this medium, it’s this logic of fluidity. All the ideas of a deluge, a flood, waves, and noise are anticipated in it—as is the fantasy of domination [Herrschaftsphantasama]—that one can glide across this sea like a surfer. Such ideas were quite common during this epoch. Benjamin Franklin, who made a name for himself not only as an American diplomat but also as a pioneer of electricity, distinguished between ordinary matter and electrically fluid matter39 – comparing ordinary matter to a sponge that absorbs water—you could say that the material World floats in an electromagnetic fluid.40 This idea of an all-encompassing electricity, that is the question of how electromagnetic space can be integrated into the traditional spatial structure, was crucial in the 19th century as a thought vehicle rendering theorems of the past unrecognizable.

Drude and Abraham set out to replace Newton’s concept of absolute space with ether, which they believed to be the medium through which electromagnetic waves travel.41 However, the Michelson-Morley experiment in 1887 proved that this carrier substance didn’t exist, and it was replaced by the free electron moving at the speed of light, as well as Einstein’s Theory of Relativity. If we analyze this development in the field of knowledge, we can say that space itself is becoming fluid, dissolving into electromagnetic waves and vibrations. In this sense, the theories developed in the 19th century still reflected the disturbing experiences and the rift caused by the discovery of electricity in the 18th century. Strictly speaking, this removes the boundary between a body and its surroundings, so it no longer makes sense to discuss incarnation in the sense of becoming flesh. Everything is wave and vibration. Mathematically, this is expressed in Hilbert space, which dissolves the concept of space as a composite of electromagnetic vibrations, allowing for as many dimensions as there are vibrations. In fact, this theorem doesn’t just mean going beyond the realm of human experience, but the complete elimination of the body.

However, it’s not the body itself that’s being digitalised, but its electromagnetic shadow (so we’re not actually dealing with the romantic World Soul, but merely with its encephalogram). This raises the question of how electromagnetic shadows are detected, which brings us to George Boole’s Laws of Thought, published in 1854. The digital logic contained within it is the symbolic equivalent of what happened in 1746. Boole’s major achievement was to separate algebra from numerical Signs, no longer viewing zero and one as representations of a thing, or even as quanta at all, but as the two poles delimiting the overall state of the system and in which things appear. The idea of a systemic, encoded space replaces that of a representative body. This algebraic space no longer simply records the quantity of things (meaning it no longer counts), but emphasizes the things themselves. It doesn‛t matter whether this X represents a number or a body. Digital logic reckons with apples, pears, and operators, and in this sense (insofar as it leaves the domain of numbers) it takes over the functions of language.42 Boole’s logic thus marks the end of Representation. In a profound remark, Erwin Schrödingerdescribed zero as the only number with a certain carte blanche, a kind of royal privilege43 – and indeed, the mathematical development of zero can historically be linked to the function of kingship and the logic of Representation. The 14th century, which struggled to resolve the Greek quadrature of A:B=C:D into a triangle – something that was satisfactorily achieved only with the introduction of zero – christened the placeholder for this solution the Representative. By assigning a new function to zero, Boole performs a kind of symbolic regicide – or rather, creates a system in which the systemic space comes before the appearance of the individual.

Interestingly, Boole develops an analogue, or rather an extension, of Aristotle’s Identity Principle. For him, the question of Identity remains the same as for Aristotle, namely: What remains the same? Boole’s answer is: Only zero and one can be multiplied by themselves without changing. One times one equals one, zero times zero equals zero. These are the only two numbers that correspond to the formula that defines the digital universe: x=x². This justification of Identity is interesting insofar as it isn't static in the strict sense, but dynamic; it can be driven further and further (Pump up the Volume) into the third, fourth, fifth power. Whether x3, x4, x5, or xn – zero and one remain the same. But what happens if this formula is applied not to zero or one, but to any physical object? This question highlights the conceptual shift in Identity. It essentially reduces it to nothing more than the copy command on a computer, which allows the production of an infinite number of derivatives of an object. This formula renders the concept of an original obsolete, as any physical object made of ordinary matter that is digitalised —meaning it is converted into liquid matter (or liquefied) —can be copied at will. It is a sample of itself, a gene pool that can spread endlessly through cell division—and in this sense, it tends to be superfluous.

Translation by Hopkins Stanley and Martin Burckhardt

See Beckett, S. – Murphy, London, 1938, p. 5.

Reading the letters of the young Camille Desmoulins, who discovered himself as a tribune of the people and a demagogue during the storming of the Bastille, provides insight into what is meant by the term Spontis today. See Landauer, G. – Briefe aus der französischen Revolution, Berlin 1999, p. 101 ff.

Der Zeitriß, literally a rupturus rifting, a rip or a crack in time that Martin will continue tracing out as a significant leitmotif in his thinking as der Knisternden Zeitriss: the crackling rift in time.

The Kleistian or Leyden jar was independently discovered by Georg Ewald von Kleist and physics professor Pieter van Musschenbroek at Leiden University a year later. It is precisely the independence of these two »discoveries,« also clearly seen in photographic development, that demonstrates how we’re dealing with ideas that were, so to speak, already in the air—pointing less to individual inventors than to a broader epistemological picture.

»I am sending you a new, truly terrifying experiment, and I advise you not to repeat it yourself. [...] I had suspended an iron bottle from two silk threads, which had been electrified by means of a glass ball that was quickly rotated and rubbed with the hands. At the other end hung a copper thread, the end of which was suspended in a round vase partially filled with water, which I held in my right hand. With my other hand, I tried to draw sparks from the iron bottle. Suddenly, I felt such a violent blow in my right hand that my whole body was shaken as if by a lightning strike.« (Musschenbroek to Reaumur, January 1746, quoted from Jean Torlais: Un physicien au siècle des lumières: l'Abbé Nollet, Paris 1987, p. 65).

This was also well known to contemporaries. For Tibere Cavallo, the great discovery of this »wonderful bottle in the memorable year 1745 gave electricity a completely new face«. See Cavallo, T. – Traité complet de l'électricité, Paris 1785, p. XXIII.

See Torlais, J. – Un physicien au siècle des lumières: l'Abbé Nollet, Paris, 1987, p. 68.

Kant’s great achievement was bringing knowledge down from the heavens of metaphysics and placing it in an earthly topography: »Our reason is not an indeterminately vast plane whose boundaries can only be recognized in a general way, but must rather be compared to a sphere whose radius can be found from the curvature of the arc on its surface (the nature of synthetic a priori propositions), but from which its content and limitations can also be determined with certainty. Outside this sphere (the field of experience), nothing is an object for it; even questions about such supposed objects concern only subjective principles of a universal determination of the relations that can occur under the concepts of understanding within this sphere.« See Kant, I. – Kritik der reinen Vernunft, Berlin/Vienna, 1924, p. 384. In a certain sense, mathematical expression also highlights Kant’s limitations, as he failed to fulfill his promise to write the history of Pure Reason (and thus to examine its vehicles). Here would be Gaston Bachelard, who has linked modern epistemology to electricity. See Bachelard, G. – Epistemologie, Berlin/Frankfurt/M./Wien 1971. Admittedly, Bachelard is writing from a hard science perspective in a certain sense. The opposite would be the sociological platitude, as defined by Rorty, exemplified as: »To construct an epistemology is to find the maximum amount of common ground with others. The assumption that an epistemology can be constructed is the assumption that such common ground exists.« See, Rorty, R. – Philosophy & the Mirror of Nature, Princeton, New Jersey, 1980, p. 316.

Durkheim, E. – The Division of Labour in Society, London 1984, p. 370.

The French Revolution also included, appropriately enough, the Metrification of the World. See Guedj, D. – Die Erfindung des Meters, Frankfurt/M, 1995.

Strictly speaking, the concept of real time is misleading. In fact, the difference between the points in space is not eliminated; it is only minimized by acceleration to such an extent that human perception of time is outwitted, and the illusion of a space oscillating in ›real time‹ arises.

»A network is a system of nodes and links that can be described by its topology and architecture. It has both a physical form and a logical one insofar as it is governed both by physical interconnections and by sets of rules that govern exchanges of energy or information. The spread of electronic networks has been matched by a widespread use of the network as a logical device or metaphor, something that is good to think with. As a metaphor, the word fills many different roles, describing grids of fibre, copper cable and radio, links of personal friendship and informal relationships in political organizations, to mention just a few. So widely used is it that the word sometimes seems to lose its original meaning, of an object in which threads or wires are arranged in the form of a net: a sense that came to include systems of rivers, canals and railways. This underlying meaning, of a set of lines and crossing points, of nodes and links, gives the idea of a network broad applicability in complex, dense and highly interactive societies.« See Mulgan, G.J. – Communication and Control. Networks and the New Economies of Communication, Cambridge/Oxford. 1991, p. 20-21. The release of the network as a mere metaphor often leads to the fact that here – quite similar to the dialectic of the natural automata in Descartes – a body image creeps in. In a speech to the British Association in 1956, A. R. Bennett described commerce and industry as the lifeblood of Britain and the roads, railways, and waterways that connect them as »the arteries through which this blood is conducted, while telegraphs and telephones may be compared to the nerves which feel out and determine the course of that circulation.« Quoted from Marvin, C. – When Old Technologies Were New, New York, 1988, p. 141.

Freud writes: »The masses appear to us as a revival of the primal horde« – and a little later: »We must conclude that the psychology of the masses is the oldest human psychology.« See Freud, S. – Massenpsychologie und Ich-Analyse, Frankfurt/M, 1967, p. 63.

Against this backdrop, the question arises as to whether it is permissible (as Habermas did in his Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere) to read media history as a history of progress without taking into account the profound rupture associated with the emergence of the electrified public sphere. See Habermas, J. – Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit, Neuwied/Berlin 51971. If it is true that the collective is formed through shared experience of writing, then the rift between the printed word [Druck-Schrift] and what I call electromagnetic writing highlights a division between two collective projects. The latter, the project of a global society, can only be partially understood. Jean-François Lyotard has clarified this connection under the heading of telegraphy: »Schools teach future citizens how to write. But which institution would be responsible for teaching telegraphy? Is an institution for teaching telegraphy even conceivable? Isn’t the idea of such an institution linked to the State and to writing and reading? In other words, to the ideal of a political body?« See Lyotard, J. – Logos et tekhnè, ou la telegraphie. In L'inhumain. Paris 1988, p. 61.

On an intuitive level, talk of puppet masters certainly reflects the nature of the new social structure. John Stuart Mill writes about the tyranny of the bureaucratic system: »which leaves no free agent in all France, except the man at Paris who pulls the wires.« See John Stuart Mill, quoted from Beniger, J.R. – The Control Revolution. Technological and Economic Origins of the Information Society, Cambridge, Mass, 1986, p. 14.

It is not without some irony that Abbé Nollet was appointed tutor to Louis XV's children, and that the Dauphin, later Louis XVI, who, having been exposed to his influence for years, began taking the apparatus apart and putting it back together. This experience left such a lasting impression on him that precision engineering, especially lock-making, became his favorite hobby, which led Marie Antoinette to remark thoughtfully that she could hardly appear as Vulcan in his makeshift workshop, but neither could she as Venus. See Torlais, J. – Un physicien au siècle des lumières: l'Abbé Nollet, Paris, 1987, p. 165.

Priestley writes »that it is more the powers of nature, than of human genius, that excite our wonder with respect to them.« See Priestley, J. – The History and Present State of Electricity, London, 1767, part I, p. XII.

Insofar, it is not surprising that contemporary evolutionists attribute immortality to information. »All forms of life have a common origin. The origin is information, which is organized according to the same principle in all living beings.« See Eigen, M. – Stufen zum Leben,Munich/Zürich, 1987, p. 50. In Richard Dawkins’s view of evolution, specimens are simply vessels that the genetic code—i.e., information—employs to attain immortality. See Dawkins, R. – The Extended Phenotype, Oxford/San Francisco 1982.

In this context, it is not insignificant that Freud liked to use metaphors relating to publications (new editions, coffee-table books). See Freud, S. – Bruchstück einer Hysterie-Analyse. In Gesammelte Werke, Frankfurt/M, 41963, vol. 5, pp. 279-280.

As will become apparent, this dimension is present in Freud's thinking in an extremely problematic, hidden way—which opened the way to Lacan's reading, or more radically, to the desiring machines of Deleuze/Guattari. See Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. – Anti-Ödipus, Frankfurt/M, 1977.

Rousseau speaks significantly of a supreme intelligence which, as Joseph de Maistre sharply remarks, represents a kind of divine machine: »In order to discover the principles of society most suited to the welfare of nations, it would require a higher mind, one that could see all human passions and feel none of them; one that lacked any connection to our nature and yet possessed knowledge of it; one whose happiness was independent of ours and yet had a tendency to concern itself with ours (…)« Jean-Jacques Rousseau – Der Gesellschaftsvertrag, ed. Heinrich Wittstock, Stuttgart 1969, p. 72; see also de Maistre, J. – De la Souveraineté du peuple. Un anti-contrat social [1975], ed./annot. Jean Louis Darcel, Paris, 1992, p. 116.

However, this shift cannot be understood solely in a historical context. In fact, electricity was regarded as a divine substance well into the 19th century; therefore, the idea of executing a human being in this way was viewed as a desecration of this miraculous substance. On the other hand, the modern serialization of death by guillotine proves that the shift in sovereignty (from the potemce, the gallows, to the electric chair) had already started in the 18th century.

See Freud, S. – Massenpsychologie und Ich-Analyse, Frankfurt/M, 1967, p. 63.

When Joseph Goebbels said that »radio was the brown house, the temple of National Socialism« (in a speech to WDR [Westdeutscher Rundfunk Köln] employees in 1933), this sacralization of the medium revealed the insight that sovereignty in modern times is established through media transmission devices.

Here, it becomes clear that classical dichotomies must be replaced by tertiary orders.

Winkler, J.H. – Die Eigenschaften der electrischen Materie und des electrischen Feuers, aus verschiedenen neuen Versuchen ercläret, und, nebst etlichen neuen Maschinen zum Electrischen beschrieben, Leipzig 1745, p. 66. – Winkler was also the one who clearly grasped and described the telematic aspect: »On the other hand, with the help of electricity, one can produce an effect at any point in time, at any distance on the earth's surface, e.g., fire a gun or give a sign.« See J. H. Winkler, Grundriß zu einer ausführlichen Abhandlung von der Electricität. Leipzig, 1750.

Basically, the musical note, which in conventional notation only indicates time value and pitch, makes the transition much clearer.

This logic can be observed time and again in the history of electricity. After successfully constructing a telegraph apparatus in 1833, Carl Friedrich Gauss wrote to Alexander von Humboldt: »In the present year, I have built my apparatus mainly for electromagnetism, and also for induction, which can be measured most beautifully with it. Most recently, we have been engaged in large-scale galvanomagnetic experiments. A wire connection between the observatory and the physics laboratory has been established; the total length of the wire is approximately 5,000 feet. (...) The effect is very impressive, indeed it is now too strong for my actual purposes. I would like to try to use it for telegraphic signs, for which I have devised a method; there is no doubt that it will work, and with a device, a letter will take less than a minute.« Sees Gauß, C.F. – Brief an Alexander von Humboldt, Göttingen, June 13, 1833. In Carl Friedrich Gauß. Der »Fürst der Mathematiker« in Briefen und Gesprächen, edit. Kurt R. Biermann, Munich, 1990, p. 153.

See Blachelard, G. – Die Epistemologie der Physik. In Blachelard, G. – Epistemologie [selected texts], Berlin/Frankfurt/M./Wien, 1971, pp.. 51-52. – It isn't an insignificant detail that the computers of the 1940s and 1950s, as designed by Turing and von Neumann, used vacuum tubes to store information. Of course, the vacuum tube was regarded as the analogue of the brain cell. See John von Neumann – Die Rechenmaschine und das Gehirn, Munich, 21965, p.48.

»SALVIATI(..) Note that I spoke of a perfectly round sphere and an excellently smooth surface, in order to exclude all external and accidental obstacles. I would also like you to disregard the air, which constitutes an obstacle insofar as it offers resistance to cutting through, as well as all other accidental obstacles, should any such exist. Galileo Galilei – Dialog über die Weltsysteme. In Galilei, G. – Siderius nuntius, edit. and intro. by Hans Blumenberg, Frankfurt/M. 1965, p. 180.

The analogous process can also be observed where the question isn't one of the transferring substance, but rather of the logic of Transfer. Jacquard's loom, which replaces the Sign with the hole, follows the same movement, as do the gear wheels that turned into punch cards during the 19th century. See Burckhardt, M. – Metamorphosen von Raum und Zeit: Eine Geschichte der Wahrnehmung, Frankfurt/M, 1994, p. 242 ff.

Here lies the connection to romantic Natural Philosophy, to Schelling, Schleiermacher, Novalis, and Ritter. Reading the texts that celebrate the unio mystica with the world soul, it is easy to recognize the experience of electric shock, or more generally speaking, nervous dissolution: »I lie at the bosom of the infinite world: in this moment I am its soul; for I feel all its forces and its infinite life as my own; in this moment it is my body, for I penetrate its muscles and its limbs as my own, and its innermost nerves move according to my sense and my intuition as if they were my own.« Schleiermacher. F. – Über die Religion: Reden an die Gebildeten unter ihren Verächtern, Göttingen, 61967, 2nd speech, p. 64.

The reception of mystical texts, from Meister Eckhardt to Jakob Böhme, is a clear indicator that the Gnostic tableau is unfolding its virulence.

See Torlais, J. – Un physicien au siècle des lumières: l'Abbé Nollet, Paris 1987. – Benjamin Franklin explains in a lecture that »artificial spider, animated by electric fire, so as to act like a live one« See Franklin, B. – »Course of Experiments«. In Writings. New York 1987, p. 355.

Briggs, Charles F., Maverick, A. – The Story of the Telegraph and a History of the Great Atlantic Cable. New York 1858, p. 13. – A little later in the same text, it says: »The inspired author of the Book of Job exclaims in an interrogatory, meant to bear the burden of the impossible, „Canst thou send lightnings that they may go, and say unto Thee, here we are?“ But this is precisely what science has done in the Electric Telegraph.«, ibid. p. 21.

Here, the ideas that patristic theology has developed on the question of Time and Eternity could be used as a conceptual model.

See Levi, P. – Die kollektive Intelligenz, Berlin, 1998. This book can be read as a transfer of the World Soul phantasm to the real conditions of communication in the Internet age. The guiding fantasy (as represented by the »grassroots movement« of Internet pioneers) consists in the formation of utopian communities that communicate with each other in self-organized, non-hierarchical spaces. However, the new communication relationships appear much more ambiguous when viewed from an economic perspective. See Schiller, D. – Digital Capitalism: Networking the Global Market System, Camebridge/London 1999. Here, Schiller, who links the Internet with the theory of neoliberalism, speaks of a de facto Balkanization and compares the closed internal spaces of the Internet (the Intranets) with the parcelling out of the community as it was in pre-civil war England in the 17th century. See ibid., p. 77.

McLuhan, M. – Die magischen Kanäle. Understanding Media, Dresden/Basel, 21995, pp. 375-376.

See, Franklin, B. – Briefe von der Elektrizität, trans. from English, with notes by C. Wilcke. Leipzig, 1758, p. 73.

The two Kinnerly Lectures given by Benjamin Franklin in 1751 are interesting evidence insofar as they briefly list the beliefs and strange phenomena attributed solely to electricity. Franklin states: »II. That electric fire is a real element, distinct from all those hitherto known and named, that it is extracted from matter (not produced) by friction with glass and other substances. – III. That it is an extremely fine fluid. – IV. That it requires no perceptible time to traverse great distances in space. – V. That it is intimately mixed with the substance of all other liquids and solids on our globe. – VI. That our bodies contain enough electricity at any moment to set a house on fire. – VII. That although it heats non-combustible matter, it does not itself exhibit any perceptible heat. – VIII. That it differs from common matter in that its parts do not attract each other, but repel each other. – IX. That it is strongly attracted to all matter. – X. An artificial spider that has been brought to life by electric fire and behaves like a real spider. – XI. A constant rain of sand that rises as quickly as it falls. (...) – XIII. A leaf of the heaviest metal floating in the air, as is claimed of Mohammed's tomb. – XIV. A phenomenon like fish swimming in the air. – XV. That this fire will live in water, and that a river will not be enough to extinguish the smallest spark of it.« See Franklin, B. – »Course of Experiments«. In Writings. New York 1987, p. 355 F. The second lesson announces an electrified coin, which no one wants to accept; how to pull a coin out of someone's mouth without touching them; how to elicit sparkling glances from a lady; how to burn a clean hole in paper, melt metal, kill animals (»if someone in the audience wishes to sacrifice one for this purpose«) using electricity, how to drive eight bells using a machine powered by electric fire, or the like.

See Jammer, M. – Das Problem des Raumes. Die Entwicklung der Raumtheorien, Darmstadt, 1960, p. 160 ff. – Ludwig Lange proposes a different formulation for describing the revolution in the concept of space: absolute and immovable space is replaced by space in motion, an inertial system.

»As to the lawfulness of this mode of procedure, it may be remarked as a general principle of language, and not of the peculiar language of Mathematics alone, that we are permitted to employ symbols to represent whatever we choose that they should represent —things, operations, relations, etc., provided 1st, that we adhere to the signification once fixed, 2nd, that we employ the symbols in subjection to the laws of the things for which they stand.« See Boole, G. – On Certain Theorems in the Calculus Variations [1838]; quoted from MacHale, D. – George Boole. His life and work, Dublin, 1985, p. 50. Against this background, it is plausible for Boole to be regarded as the founder of Information Science. See McHale, ibid., p. 72.

See Schrödinger, E. – Die Struktur der Raum-Zeit, Darmstadt, 1987, p. 11.

Related Content

In the Labyrinth of Signs - I

The following text is part one of the second chapter from Martin’s second book, titled »Vom Geist der Maschine. Eine Geschichte kultureller Umbrüche«, published in 1999.

In the Labyrinth of Signs - II

This is part two of the second chapter from Martin’s second book, titled »Vom Geist der Maschine. Eine Geschichte kultureller Umbrüche«, published in 1999. You can find part one here:

The Psychotope

The following text appeared in German in Lettre International, No. 146, Autumn 2024. Since the Universal Machine and its Psychotope are such central leitmotifs to Burckhartdian thinking, we’ve translated the text for our English readers.