This is part two of the second chapter from Martin’s second book, titled »Vom Geist der Maschine. Eine Geschichte kultureller Umbrüche«, published in 1999. You can find part one here:

Martin Burckhardt

In the Labyrinth of the Signs – II

Shame of Minos

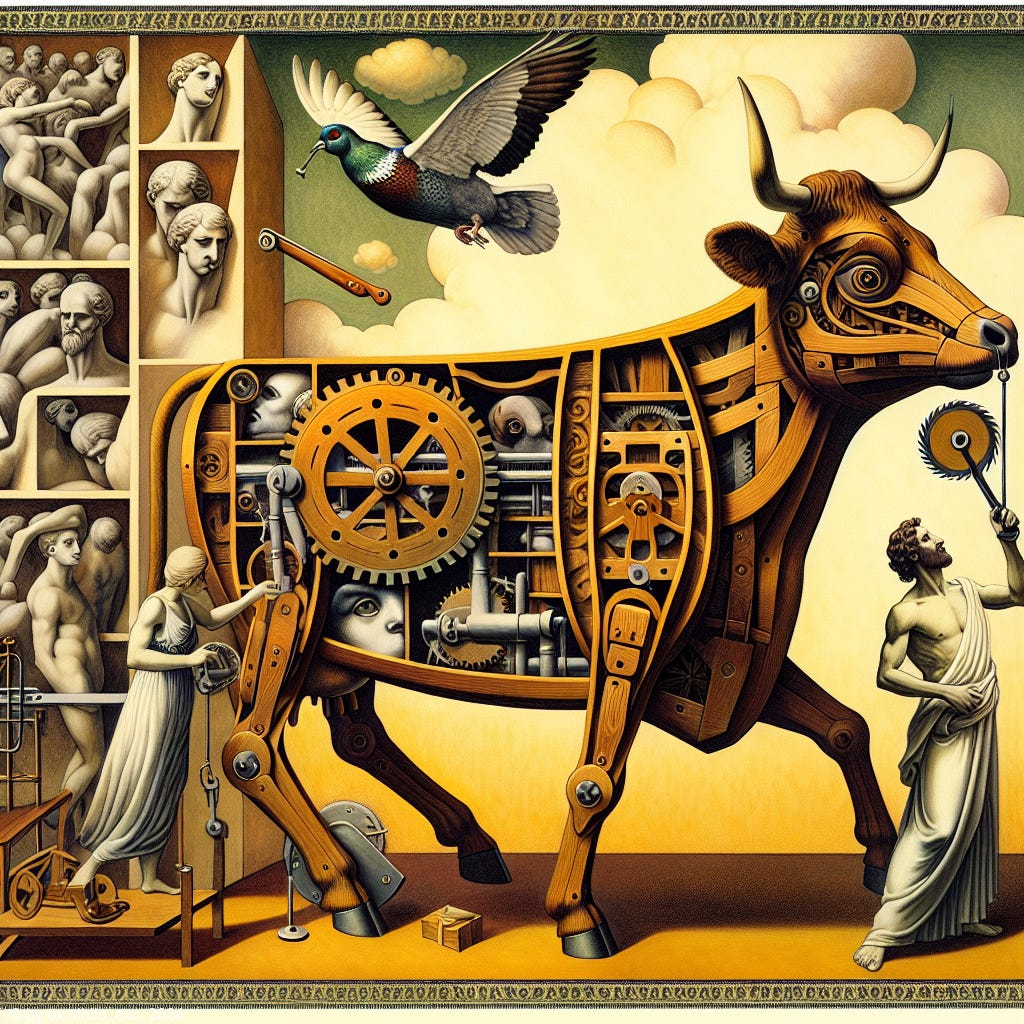

Back to the island of Crete, where the unfolding of the Greek pantheon’s ending begins, reigns Minos, son of Zeus and Europa. This king is a lawgiver, a despot, a warlord.1 His iron-clad ships crisscross the sea, conquering the surrounding islands and mainland cities. Unassailable from the outside, his inner self is fragile. Like the guardian Talos, he's also torn by a seam, an irresolvable conflict. The fertility goddess, whose sign is the Bull, prevails in his palace at Knossos, where the bull’s gilded and decorated horns represent the highest object of the Cretan cult. On the other hand, the language of power and might [Macht] has been passed to the Curetes, the bronze race that embodies the Cretan kingdom’s superiority.2 In the theater of Minos’ Palace, sacred bullfights take place in which the bull isn’t killed.3 Instead, young acrobats are seen vaulting over the bull. The act of leaping over the Bull, an initiation rite for Cretan youths, signifies a moment of hubris—in fact, it deprives the fertility goddess of her rightful sacrifice. Perhaps Zeus' disguise as a bull, which appeared to Europa on the shores of the Phoenician Sea and abducted her to Crete, was already a first step in this direction: a kind of travesty finding its logical expression in the theater, in the evasion of the bull sacrifice. Additionally, Minos fails to sacrifice the white bull emerging from the waves of the sea one day. This theft of a sacrifice marks his misfortune’s beginning. From that point on, Minos is plagued by all kinds of calamities. His fertility suffers – he can now only father monsters: snakes, scorpions, centipedes.4 The Bull’s semen has lost its miraculous power—or, more precisely, has taken on a power of its own that cannot be controlled. The white bull, which Minos didn't want to sacrifice, goes wild. Pasiphaë, Minos' wife, also goes wild upon seeing this white and smooth bull. At the sight of the white and smooth bull, she falls in love with the animal, and with such passion that she asks the artist Daedalus to create an artificial wooden cow to be with the bull from inside this prosthesis. The Minotaur is born from this union, which, translated back, means the bull of Minos. As a human being with a bull's head on his shoulders, this bastard, the horned Minos’ badge of shame, can only be kept in check by constructing a labyrinth of containment.

While King Minos appears to be a great and feared ruler, and at times even an exemplary one,5 the Bull represents a series of humiliations—it symbolizes his ongoing loss of power. Not only must Minos defend himself against his wife's illegitimate child, but his natural son, Androgeos, also falls victim to the Bull: the wild bull of Marathon. Furthermore, Ariadne, who betrays her father's powerlessness to Theseus, the mortal enemy of Athens, will also become involved with the bull-headed Dionysus. In all of Minos’ stories, there are twists and turns. The theme of nemesis and atonement for the sacrifice taken away is present. What was once a symbol of fertility becomes a symbol of infertility – or rather, it gives birth to monsters, beasts, and hybrids that will ultimately destroy the order Minos is still trying to preserve. In this sense, Minos' conflict is personified in the figure of the Minotaur. But what’s this strange creature? This human being with a bull's head on his shoulders. In Ovid, the Minotaur is merely an image of the horned husband, »the shame of the house«,6 which must be hidden. This verdict, showing that tragedy has already clearly marked the bourgeois mourning drama, expresses the morality of classicism, which opposes the gods’ world of archaic hybrid creatures and chimeras to the resistance of the cultivated one. The same resistance makes the bull-headed Dionysus a foreign body in the Homeric world of the gods. The duality of god and bull, of Jovi and Bovi, has nothing disreputable about it in archaic times, since Zeus himself (as his series of bull marriages shows) loves to appear in the form of a bull. A reflexion of this religious significance also comes to the Minotaur. His epithet is Asterios – indicating he is a star being.7 Human sacrifices are made to him as part of his divine origin. However, Minos, once again skipping the sacrifice, doesn't recruit the virgins and young men consecrated to the god from the Cretan population. Instead, as punishment for his son Androgeos’ murder, this blood tribute must be paid by his arch-enemy, Athens. Nonetheless, the appearance of this star is undoubtedly associated with an ill omen – a dark fate. Thus, the implication that the king will henceforth only produce monsters, snakes, and centipedes is a Sign of a profound disturbance – namely, in that which the sacrifices are intended to serve: fertility and general well-being. What manifests as an economic disruption affecting both the victim and the general welfare follows an inner necessity—or, more precisely, it marks a shift in the bitter necessity, the tyche. If the Bull stood at the center of cultic life in an agricultural culture that discovered writing, then the sema of the Bull must lose its miraculous power—and to the extent that Cretan culture pays homage to telluric sacredness. But this replaces the old nature deities with cultural deities that are now under threat of being branded as all too human. Even the Bull, utterly contrary to its nature, is incorporated into the order of cultural signifiers. This corresponds to how the Sign of the Bull undergoes a reversal in Crete, becoming both depotentiated and idealized, and becomes the ideogram of love.

Of course, as the fate of Minos and Pasiphaë shows, this process of idealization and aestheticization is by no means a harmless game; instead, it unleashes fantasies that challenge the times to the utmost. It could be said that the more theBull is subject to control (in cultural history: the more agricultural cultures internalize fertility laws), the more it takes on a new, uncontrollable power. However, this only seems paradoxical at first glance. If you consider the Latin word factitius, which means: artificially made or manufactured, you observe a very similar development because the fetish derives from factitius. This historical transformation is traceable from the Bull to its Zodiac Sign, from the force of nature to the fetishization of the phallus. Translated into a formula (which would also have the advantage of physiognomic conciseness), it can be said that the Bull goes to the head of thought. The Minotaur would thus be the Bull in Thought, the aestheticized, symbolic force of nature that now begins exerting a phantasmatic effect. Pasiphaë’s desire is not fueled by the desire for procreation, but signifies nothing other than the smooth and white bull itself, the ultimate phallic symbol. It's not the bull robbing the woman (as in the story of Zeus and Europa): instead, it's the woman who robs the bull, which puts Pasiphaë's lust in a certain gender-specific symmetry with the Minoan sacrifice. Logically, this double sacrifice takes the form of the Minotaur, a pervertedly twisted fertility god. Its mechane, meaning »the deception of nature,« is what constitutes the scandal – and indeed, nowhere is this more clearly visible than in the wooden apparatus, this prosthesis of lust, by which Daedalus enables Pasiphaë to take possession of the sekretum. Against this background, the myth describes a series of shifts: from the dark force of nature to the Sign, from the Sign to the space in which the Signs appear. The Minotaur himself is the hybrid being that embodies this transition. Seen in this light, it would most accurately be captured if Lacan's beautiful play on words were applied to it: alphabête, Alpha-Beast. But this seals its fate: if the Alphabeast is to become Alphabet, the beast must disappear.

Daedalus. Schizo

In ancient times, Daedalus was considered the epitome of the artist: the Sculptor. He's said to be the first one to open the eyes of statues. Plato tells us of his sculptures’ liveliness: how they had to be tied down to be kept from running away.8 Some of his statues simply walked away while the temple guards had their backs turned.9 If the inert mobility of these statues is evidence of artistic skill, then the master's most significant work of art must be the artifact not appearing in his works catalog: the wooden cow he built for Pasiphaë. But what kind of work is this? Here, the conception of artwork coincides with conception in the sense of reception—this is the purpose imposed on the master by Pasiphaë. For only through Daedalus' work of art can Pasiphaë come into possession of the divine sekretum. In a sense, the master's method is a somewhat crude, legendary form of what Socrates later conceives of as the Philosopher's most noble task: to be a midwife, to serve the maieutics of thought. The Bull, the Sign Aleph, inscribes itself into the medium created by human hands, and from this connection between divine Sign and human ingenuity springs forth the Minotaur, the hermaphroditic creature.

The comparison with Socrates is illuminating insofar as Daedalus isn’t merely a figure who brings something new into the world (the mechanical sculpture); he is also a master of making things disappear. This is the double movement of abstraction: that which appears conceals something else from view.10 Indeed, Daedalus' situation is highly paradoxical. His work of art is meant to achieve what nature cannot. He’s supposed to give Pasiphaë the strength of a bull, but the medium he devises is a simulacrum: a mechanical cow. The Greeks translated mechane as a »deception of nature,« which can be read as a secularized continuation of deceiving the gods, as in the theft of sacrifices. However, Daedalus' skill doesn’t prove to be a blessing, because every theft results in a curse, for his artifacts give rise to hybrid creatures, which in turn necessitate the construction of a new artifact. The Minotaur must be hidden, he must be concealed in the labyrinth—the Sekretum of the god is replaced by an order whose statue aims to make the Minotaur invisible.

If Pasiphaë's drive [Antrieb], as a liberated lust, is immediately apparent to us, we might ask ourselves what drives the artist Daedalus. Psychoanalysis might suggest the Jungian castration complex, but the myth tells a different tale, that of redemption and revival. Daedalus, an Athenian by birth, is a stranger in Knossos – an exile and a refugee. He’s also what might be called a schizo, a figurative form uniting the rift within himself that divides him. Schizein literally means: to divide, which is precisely how Daedalus’ story begins, long before entering the service of King Minos. It begins with Daedalus, who works as a stonemason in Athens, feeling the impulse while cutting stone to split the raw stone in two with a fine, clean cut instead of breaking it apart. To do this, he devises a plan to cut teeth into a metal blade, thereby constructing something like a saw. Now Daedalus has a student (named Talos!) who eagerly emulates his master and, being incredibly talented, surpasses him. He perfects his master's invention by replacing the saw blade with a circular metal disc with teeth. The construction of this circular saw arouses such jealousy in Daedalus that he kills his overly studious pupil. When the citizens of Athens catch him burying the body, he pretends to be burying a snake – but his deed is discovered. He is banished, and the story of his exile begins with this banishment. In another version told in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the student is transformed into a partridge when he falls.

Just as Minos interrupts the cult of sacrifice, wherein after everything that happens to him takes the form of a bull—Daedalus is his inverted mirror image. Although all his deceptions succeed after being caught and banished once, the crime of stolen knowledge returns in his artistry. As with his sculptures, which suddenly run away as soon as someone turns their back on them, so it is with all his artifacts: they take on an unpredictable life of their own, which can only be controlled by another device, which today is the mechanism referred to as a material coercion of practical constraints [Sachzwang]. Because the Minotaur must be hidden, Daedalus is forced to build a cage [Zwinger]: his famous Labyrinth. He constructs it so perfectly that he cannot even find a way out. Cursed to be locked within his self-made dark labyrinth with the Minotaur, he devises a means of escape: artificial wings coated in wax, with which he sets off on his famous flight of abstraction, taking his son Icarus with him. Icarus flies too close to the sun, melts the wax, and falls from the sky. Whatever Daedalus does, whatever flying or escape devices he devises, he cannot escape the curse of hubris. In a sense, his art comes to an end with the death of his natural son: »And he curses his art and buries his son's corpse in the grave.«11 At the moment of burial, a partridge appears,12 rejoicing over the death of Daedalus' son.

When it's said that the student Talos/Perdix invented not only the circular saw13 but also the compass, this little detail highlights how circular the story is. The instant [Augenblick] when the father buries his son's body marks not only Daedalus' shame and the reversal of the natural order, but also creates a perfect circle. The fall of Icarus is cheered by that strange bird creature, which, traumatized by its own fall into the abyss, doesn’t honestly wish to fly. Daedalus' transgression, the theft of knowledge, seems to have been atoned for. Moral balance has been restored, yet there can be no question of a return because everything has changed. Daedalus' path is lined with metamorphoses and transformations, all seeking to deceive nature. Just as an artifact responds to the unforeseen life of its predecessor and drives the artist deeper into the labyrinth of his mind, this path leads him from one exile to the next. The Hybris that was so suspect in Greek culture is reflected in the father's instruction to his son to maintain the right balance, characterizing the artifacts of Daedalus. Hubris—that is not only arrogance and conceit, but it also marks the products of this desire: the hybrids that spring from the deception of nature.

The Labyrinth

The labyrinth of Daedalus marks a new kind of boundary: between inside and outside, between raw nature and an architecture that creates its own laws. One could call the labyrinth a magic circle [magischen Zirkel]. More precisely, as an enclosed space, it symbolizes the circle of knowledge itself, revealing that knowledge is contained within a corset made by human hands.14 This knowledge isn’t abstract, nor is it what’s referred to as dead letters—rather, it embodies the laws of fertility, the Bull’s sekretum. It is the Bull that’s gone to the head. It is essential to remember the original form of the labyrinth, which was not yet a structure, but merely a hole in the ground, a cave. These cave labyrinths were sites where initiation rites took place. They also served to consecrate bronze artifacts,15 the cult of Prometheus. Continuing this line of thought, the labyrinth appears as the logical counterpart to what the ideogram of the snake conveys: the secret knowledge of reproduction.

However, there is a significant shift here. The labyrinth reinterprets the concept of domination. While the crossbar of the Alpha still hints at the triumph of having forced the Bull into submission, the domestication of the Minotaur no longer takes the form of physical coercion; rather, it manifests through dominion over space, over confinement. To control a body, it is no longer necessary to chain it; it's enough to control the space in which it appears. The letters of the Alphabet also experience this confinement because the semantic constraint no longer comes directly from the letter’s shape, but from the Alphabet’s circular form. When we speak of a magic circle, the magic of this labyrinthine Alphabetical circle lies in its inherent genetic power. In this sense, the cavity’s transpositions are decisive, encompassing the place of birth, the metallurgical workshop, and the abstract, logical space of the Sign.

However, as long as the labyrinth harbors the man-eating monster, as long as the Alphabeast hasn’t yet attained the immateriality of the Alpha Sign, this place hasn’t fulfilled its destiny. But what might that destiny be? Another myth could provide some insight here. Apollo, who ordained a Cretan priestly caste at the oracle site of Delphi—the place originally belonging to a female dragon named Delphyne (meaning womb, uterus)—wants to build a temple there. This temple has a strange shape. Bees, it is said, built a temple for Apollo out of wax and feathers, which the god sent to the land of the Hyperboreans, from where he returned every year. Seen in this light, the function of the labyrinth would be its abolition – or, if you will, the portability of this knowledge. This is precisely the solution Daedalus chose: armed with wax and feathers, he sets off on his flight to the heavens.

Mythology tells of another way out of the labyrinth in the famous story of Ariadne, the natural daughter of Minos and sister of the Minotaur. Similar to another great heroine, Medea, who kills her own brother (or Scylla, who betrays her father and kingdom out of love for King Minos), Ariadne embarks on a path of betrayal against her home and family for the sake of a stranger (which led Roberto Calasso to remark that betrayal is the heroism of women16). This stranger is Theseus. To enter the labyrinth, he has joined the ranks of the Athenian boys and girls destined to be sacrificed to the bull. Theseus is well prepared for what awaits him: he is, after all, a famous bull-slayer and womanizer. It was he who slew the bull of Marathon, the presumed father of the Minotaur. Ariadne, who has fallen in love with the young hero, shows him the way through the twilight with a glowing wreath or diadem. In this way, the hero reaches the interior, where he finds the Minotaur asleep. On some vases, Hero and the Alphabeast can be seen facing each other in a duel. Theseus has a sword – the Alphabeast only has a stone in his hand. The inequality of their weapons already reveals the outcome of the fight. However, the decisive detail of the story lies less in the fight itself than in the question of how he’ll navigate his way out of the labyrinth. Only with the help of Ariadne's invention, the thread, does Theseus manage to find his way out of the labyrinth. This thread, if you will, is the pattern of writing, as it enables the hero to find his way out of the labyrinth of Signs, to move forward sentence by sentence in that cryptic text that writes the legend’s fabric and from which the great Attic tragedians draw their material.

Read in this way, the labyrinth essentially appears as a texture, as a text desiring to be read and deciphered. Here, geometry and narrative, text and architecture intersect, revealing that the story of the Bull, which (guided by the maieutics of Daedalus) descends in the form of a bull-man, and is about a System of Signs. The mastery of the Alphabeast makes sense when a ribbon connects the Signs. In this sense, the shining diadem, Ariadne's halo, acts as a kind of enlightenment program, while the thread is the chain connecting the Signs.

Just as the sekretum of Talos (which can not withstand Medea's gaze) doesn't disappear from the world, but instead becomes at home throughout the Mediterranean world with the departing Cretan ships, so too does the labyrinth, which the Athenian hero leaves victoriously, become portable, as it were: a brightly shining circle of symbols. It’s said that on his way home, the hero performed a round dance that imitated the labyrinth’s pattern and twists and turns. In this dance, which accompanies a thank-you offering to Apollo, the labyrinth finds its purpose, for here the hermetic architecture of Daedalus is transformed into a mastered form, a form that has ceased to be a prison and instead conveys itself light-footedly in the dance of the dancers. Theseus has made the knowledge of the labyrinth common property, so upon his return, he is elected king.

Ariadne

And Ariadne? Ariadne stays behind, abandoned by the hero. Out of lovesickness, it’s said, she hanged herself on Crete, or died in childbirth without giving birth. This circumstance is commemorated in a Cypriot cult dedicated to her, in which a young man acts as an artificial mother in a mimesis of the birth process. According to another version of the myth, Dionysus17 stole her from Theseus. Whichever version one prefers, they all agree that Ariadne must remain behind. There is an inner inevitability to this. Because Ariadne, like Persephone, a kind of goddess of the underworld, is part of that world whose passions are deeply interwoven with the world of the Alphabeast. If the function of the labyrinth is to preserve itself in the form of socially mediated knowledge, the mistress of the labyrinth represents a relic that can only survive in idealized form, as a statue. As a result, she’s left behind and doesn’t follow the path into abstraction, into the realm of mere symbolic witness.

This touches on a leitmotif constantly recurring in the stories about gods and heroes: that of the women left behind. Whether it's Medea, before whose eyes the secret of Talos expires, or Ariadne, who reveals the labyrinth's secret—these figures embody the homesickness and longing for that vanished world. To the extent that the law of reproduction becomes a SIGN-making process [ZeichenZeug], to the extent that Signs become homogeneous and in turn produce uniformity [Homogen], femininity (as the mystery of birth and procreation) loses its meaning. If the cult dedicated to Ariadne has a young man demonstrate the process of birth, it marks, as it were, the problem’s endpoint that began with the suffering Rhea and the mountain in labor: for in the future, the secret of social reproduction lies with that priestly caste that knows means other than natural ones.18 In this sense, the image of Ariadne giving birth and dying serves as a symmetrical counter-image to the myth of Zeus, who swallows his wife to give birth to his offspring, Athena, from his head, as a pure brainchild.

It's strange to have wings. Fingers covered in feathers, arms like wings. And the feeling of wax on my skin stretches as if I were being embalmed, like a pharaoh, only while still alive. The advantage is that I can feel what eternity feels like and what it's like to live as an artificial bird. It's not unpleasant. This relief, this happiness, comes from being able to simply shed the weight of my body like a skin that’s become superfluous. When I lifted off the ground, I thought what a strange sight it must be: these feet lifting off the ground (and for some reason, I felt that my pair of shoes should remain behind). An imprint, a trace at least, like bird tracks, scratches in the sand. They say typoi in the language I spoke. But nothing. It was quite simple: I breathed, felt the air entering me, and there I was, already in the air. And how easy it is (if one may say so) to become lighter in an unstoppable upward movement, like a column of smoke or the breath that escapes from one's mouth on a cold winter day. And then, when I heard myself involuntarily utter this long Aaaa, I saw the Sign in front of me, a large calligraphic A, and understood for the first time that it showed my body, my two legs spread apart and my arms pointing toward the sun like an arrow. Below me (it now makes sense to say ›below me‹) lies the labyrinth I built—in which I was trapped all those years—and I see my shadow circling above it, the shadow of my body, the shadow of the flapping wings. I see the Minotaur. Perhaps I am mistaken; perhaps it is just my own shadow, but it seemed to me that I saw him wandering through the corridors. He will roar with rage because of me—that is far away; I can no longer hear anything; I am already much too far away.

How beautiful it is to see the labyrinth from above. It's as if I'm only now beginning to understand the plan I carried out back then, blindly. Now that I'm floating above it, light as a feather, the circular order reveals itself to me. It's as if I can see my thoughts, as if I can look inside my head – and suddenly it seems to me that it is myself, the labyrinth, the island, the water, and the movement of the waves in which the sky floats and the clouds....

Bull in the Head

The death of the Minotaur tells us that revolution, the reversal of the Sign, marks not only a continuation or further development of the Sign as a tool but also a profound upheaval of the religious and social order. Insofar as it’s no coincidence that the end of the Cretan world around 1450 BC ushers in the long period of darkness historians call the Dark Age of Antiquity: plague and destruction, the migration of peoples, and the turmoil of the Trojan Wars. Out of this darkness finally emerges Cadmus, the hero, and with him the Greek Polis – with such unheard-of complexity, unparalleled anywhere, that this sudden appearance has repeatedly been described as a Greek miracle (Ernest Renan).19 However, evoking genius obscures more than it illuminates—and if there is anything to be gained from the astonishment of historians, it’s that the ineffable horizon of the Lost Form analog will become the driving force [Triebkraft] of future historical process. It's precisely this driving force that becomes abundantly clear in the Alpha Sign. Because its effectiveness lies not only in what the Sign says but more precisely in what it doesn’t say. Alpha does not merely say A=A; it also superimposes the pictographic function, the image of the bull—and this superimposition represents this condition-of-the-possibility for this-worldliness-of-Signs to unfold in any way at all. But here the essential question arises: How could this blending process have been possible in the first place? How is it possible to constantly overlook what even a child could see: that the Alpha, turned upside down, looks like a Bull's head? The answer is simple but momentous. If this oversight succeeds, it’s because one sees only the metaphysical Sign, but not the physicality to which it owes its form.

The fact that this process of continually overlooking the visible, the suppression of pictographic meaning, is necessary is based on a profoundly changed conception of Signs. The individual alphabetic Sign isn't regarded as such, but only as part of a whole that, in turn, represents the totality of sounds – or, more precisely, is nothing but sound.20 The Sign is stretched across the Typewheel [Typenrad] of Signs, and it's only through its interactions, in the symphony of sound Signs, that this machinery makes sense. When Cadmus marries Harmonia, her name says it all. She embodies the circular energy that's inherent in every system of thought. If one attempts to translate the Typewheel of alphabetic Signs into an image, the labyrinth of Daedalus comes to mind. Just as the labyrinth of Daedalus serves to conceal the Minotaur, the logic of the Alphabet contributes to rendering the pictographic dimension of the Sign invisible. The encapsulation precedes the appearance of the metaphysical Sign and ultimately the liquidation of the image value: Iconoclasm. — When we spoke earlier of how, in the labyrinth, domination over a body no longer requires direct coercion but is mediated through the cage, that is, through the space of domination, we we can then say the aspect of fertility is also transferred: from the individual Sign, as the alpha-phallus Sign of Taurus, to the labyrinth of Signs, that systemic cycle formed by the Alphabet. This is the function of the killing of the Bull. Only when there’s no longer a privileged Sign of fertility in the system can the phantasm of fertility pass over to the system, which in turn keeps the Signs running in circles: en kyklos paidein. Encyclopedic discipline takes fertility into itself and, as a result, articulates itself first and foremost as Natural Philosophy. The bull, risen to the head and transformed into abstraction: logos spermatikos.

Closed world

The Signs of the Alphabet describe an empty, closed space. The closure is twofold. First, the physical world is shut out—so things and living beings can no longer cast their shadows into this space from now on – and second, the Sign space itself becomes a totality, which expands the cage to infinity to such an extent that the World’s no longer perceptible. These two related points distinguish the Alphabet from its precursors: the notation of vowels and the concept of a system. Because the Alphabet describes a closed cycle, it can encompass the fantasy of wholeness (the Holon, the World) within itself. In today's terms, one could say that the Alphabet represents a Symbolic Machine. It may seem confusing at first to speak of a ›Machine‹ here—but this term is accurate in a crucially precise sense, namely when we understand the Machine as representing a symbolic cycle [Kreislauf], which is the characteristic feature of everything we call a ›System‹ and which is usually only a variation of Wheelwork [Triebwerk] and Control Loop.21

It’s precisely this idea of the symbolic cycle that reveals to us what myth can only tell us fragmentarily or in dark images: that the hiatus detaching the Alphabet from traditional forms of writing consists precisely in how the symbolic, taken entirely on its own, is capable of becoming a cycle, and that the world can now be understood as a Machine. The circular shape [Kreisgestalt]—this distinctive archaic form22—contains the incision marking the Alphabet’s uniqueness. One could envision the circle as a skin, a membrane isolating the Sign from the physical world, thus creating an abstract, symbolic wholeness. In a sense, this wholeness is like a cover, a symbolic order under which the physical world vanishes just as a monk's body disappears under his robe. This detachment from the physical world seems essential to me, not only because it creates a barrier between Thing and Sign acting as a cutting disc that henceforth divides the World into signifiers and signifieds, but also underscores the shift in meaning accompanying the advent of the Alphabetic Sign. For the Sign system, which runs in circles, marks a new field: an inner space governed by its own laws—the Labyrinth of Signs. Nothing will penetrate this closed edifice of thought; nothing will be able to contaminate the purity of the Signs. Here comes a final point, and probably the most significant in the history of ideas – the point where the Mind in the Machine, as it were, leaps into the religious realm. Whereas earlier forms of writing were influenced by semantics, and a change in the outside world necessitated an adaptation of the symbolic apparatus (adding a pictogram as an exemplar), the closed inner space of the Alphabet opens a sphere detached from the world and time. In sharp contrast to the animal deities that die and resurrect with the changing seasons, this is cut where the assertion of eternity takes shape, simultaneously harboring the idea of comprehensive fertility—as if everything had already been said and done. The relationship between Time and Eternity, which the Philosophies of Christianity and late Antiquity will elaborate as its ultimate hypostasis, is already prefigured here as absolute stasis. »In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and God was the Word (John 1:1).« The Alphabet appears like a primordial cell (cage) containing within itself the pleroma, the fullness of being. Just as the relationship between Body and Sign is inverted, so too is the relationship between Time and Eternity. If the Body is considered a form of decay, a bastard of a metaphysical archetype, then Time is also regarded merely as a shadow of Eternity, the mere materialization of a pre-existing Form.23

This event's religious significance seems to be the crucial point: the revelation of the god of Writing. This, however, implies the possibility of understanding the Religion of Writing [Schriftreligion] in the simplest, most paradoxical sense: as a Religion of Writing [Religion des Schrift] itself. Just as God created Man in His own image, so every word and every thought will be formulated in the image of the Alphabet, just as everything must return to this first Circle of Signs.24 The second commandment also holds true: for this iconoclastic God of Writing, who is invisible like the voice in the burning bush, has banned images. In this sense, every Gram—even if it still carries the moment of imagery within itself in the verb of writing, graphein—already embodies an ascetic ideal that is virtually unattainable for mortals.

At this point, where we can already sense how ancient Philosophy, and especially the Logos-theology of Christianity, are taking flight to soar into the heavens, it's helpful returning to the birth of these figures of thought, to Zeus in his diapers, who first saw the light of day in a cave in Crete. The fertility of Signs may have replaced animal power, and the idea of logos spermatikos may have taken its place, but we mustn't forget that what is ›delivered‹ in bronze casting from its lost form has first been destroyed and completely annihilated in its own physicality. In this sense, the Alphabet itself can be read as a hollow mold: a generative nothing, a vain procreation. However, this process reprograms the body's constitution. Just as in lost-wax casting, each mold is preceded by the molten metal, as wax and bronze must be melted into an isomorphic magmafied mass. The concept of the Alphabet’s system brings about an indifference of types: it makes no difference whether one letter value replaces another. If one letter counts for as much as another, it's because the Signs have been through the fire, having suffered that symbolic death. That's the price exacted by the Pure Sign. Every form that must pass through the kenon of the Alphabet will henceforth carry with it this moment of annihilation, this memory of the Lost Form.

The Scandal of Philosophy

It isn't only Zeus alone who sees the light of day in the Cretan cave; here, long before its own awareness, is also prefigured that form of thought we call Philosophy. Significantly, philosophical thinking begins with speculations about Natural Philosophy. Regardless of which element is favored- whether it’s Thale’s oceanic substance, the Heraclitean fire, or the Pythagorean fundamental unity of the number 1—or more precisely, since the Greeks write numbers as letters, the Alpha Sphere 25—all of this, insofar as it constitutes the essential prerequisite for such thought figures, boils down to the thinking of the Alphabet. In fact, reading the pre-Socratics takes on a new meaning when read in light of the Alphabet, this generative Sign Space, which in turn imposes specific laws. Heraclitus' cryptic figures of thought are the chanting chorus of the Alphabet's laws: »Connections: wholes and non-wholes, things coming together, things separating, things resonating, things falling apart; thus, from everything, one, as from one, everything.«26 What troubles Natural Philosophers is the relationship between the element and the whole, the holon and the atom, movement and rest. Translated into an image, it could be said: the cenotaph of the Minotaur, the labyrinth of Signs, gradually fills with the Chimeras of Philosophy: with the mind that Heraclitus attributes to fire, with Parmenides' Being, the One and abstract god who is hearing and seeing (Xenophanes).

However, when we speak of Natural Philosophy – insofar as it's understood as a systemic cycle according to the Alphabet's logic – it does not contain an image of physis, but rather that of mechane, the abstract Machine with which Daedalus tricked the Minotaur. Consequently, it is NOT about physis, but about metaphysics, in which physis no longer poses a problem: it’s a question of the ideal body. This, however, brings into play the cartoon accompanying not only the revolution of the Alphabet, but also subsequent revolutions of thought. The mechanism of self-deception, which ultimately leads to those great metaphysical constructions, is extremely simple. It consists of ignoring or misinterpreting the idea, the basic tool of thought, as a Force of Nature. However, when we speak of Natural Philosophy, insofar as it's understood as a systemic cycle, according to the Logic of the Alphabet, it doesn't contain an image of physis, but instead that of mechane, the abstract Machine with which Daedalus tricked the Minotaur. Consequently, it is not about physis, but about metaphysics, in which physis no longer poses a problem: it's about the ideal body. What we call Nature is really just the camouflage of a symbolic apparatus. However, it is impossible to admit this fact, because Xenophanes' criticism, which refers to self-made gods, would also apply to self-made Machines of god. For this reason, people strive to pass off the Machine as Nature, which can only succeed if it is cleansed of all traces of human intervention and the appearance of the unmanufactured is created. Only then can it be assumed to be an original body—or›natural‹. The advantage is obvious, because the Machine, now called ›nature‹, is known in advance. Thus, what purports to be an analytical process is always already synthetic. In an extremely flippant yet unbeatably straightforward manner, Apple founder Steve Jobs summed up this intellectual leap: »The computer is the solution. What we need is the problem.« This logic, where synthesis precedes analysis and what is to be revealed about things is always assumed in advance, has been inherent in Philosophy from the beginning. In this sense, Greek Natural Philosophy can be understood more as a literacy campaign in which the logic of letters is imposed on a presumptive nature purified of the gods and dark forces.

In an early Platonic dialogue, the Cratylus, where Plato has Socrates develop his theory of ideas, this misunderstanding can be traced back to its origins in a conclusive and grandiose manner. When Socrates calls himself an heir to Daedalus, it is noteworthy that he focuses only on the positive aspects of this inheritance, excluding its dark side. This distinction becomes clear in the ambulatory sculptures of Daedalus, which Socrates states have value only as bound objects, but not as wandering ones.27 With this statement, he separates the positivity of the artifact from what is also inherent in it: its transience. In the same way, the Labyrinth becomes a temple of pure reason.

This position deserves closer examination. In Cratylus, Socrates sketches the figure of the word creator, who is the rarest of all artists among humans—and who therefore has the function of a lawgiver. The emergence of the lawgiver, in whom the figure of the philosopher-king is already foreshadowed (as is later elaborated in the State), possesses an inner logic. According to Socrates, the right to name things originally came from the gods, from those who dwelt on high and understood the heavens. The name Zeus, for example, as Socrates knows how to explain etymologically, already reveals its true essence: as the giver of life and a pure, unclouded mind. According to this etymological program, the World of the Heroes can also be interpreted symbolically: »so that the heroes mean orators and interrogators«, and »this whole heroic tribe becomes a race of orators and Sophists.«28 If the name is of divine origin, as the breath is understood as a kind of divine spirans, a soul, the question is whether and to what extent this divine origin is still recognizable in light of the transformations that words undergo at the hands of humans. Why do things have different names? Since Socrates admits the possibility of semantic corruption, any etymological procedure, and therefore the search for the true logos (the etymo logos), must always take this corruption into account where the words themselves are concerned. For this concept of mimesis, ideally conceived, amounts to a complete duplication of the object: »We would then have to concede to those who bleat after sheep and crow after roosters also that they name what they imitate.«29

At this point, when the question arises regarding what constitutes an adequate designation, Socrates brings the letters into play. He explains that the letters contain the original driving forces. The R, for example, represents the element of rolling and movement, the organ of movement 30– and analogously, every letter has its elementary function. Even if incorrect usage has corrupted the correct naming, it is still possible to arrive at the correct naming through insight into the original divine meaning of the Signs. Accordingly, the art of naming consists of assembling those original entities. 31The Kratylos thus anticipates a theme that’s preoccupied minds ever since, as an idea that can no longer be dispelled: the idea that it's possible to find one's way back to the original language by assembling the most advanced sign system. A further ambiguity is inherent in this idea, because insofar as the letters are both known and of divine origin, they belong equally to both zones; they are physical and metaphysical at the same time. In this ambiguity, however, the double bookkeeping is already laid out, which will express itself in the antinomy of Sacred Scripture and the Book of Nature. Socrates’ ingenuity (his discours de la méthode) consists of bringing the sphere of letters into the realm of pure essences. Although words are corrupted by use, letters are not. On the contrary, they articulate the unmixed, the identical, which enables the word picture to form the great, the beautiful, and the whole. Thus, if they are endowed with pure elements, things can be spelled out again. It is obvious that and why the »pure letter,« the unmixed atom of the divine, becomes the secret archetype of the Platonic doctrine of ideas.32 A prerequisite for this operation, which inspires Plato in his speculations on the Logos, is to ignore the historicity of the Sign toolbox—something that was already successful in the time of Socrates, as the argumentation proves. However, the Letter not only leads to those higher spheres that Christian Logos-theology will later take up. As already noted, it has a highly earthly fall side that will inspire the materialism of pure Signs. It is primarily Aristotle who lays this trail: namely, in the Organon, where he expands the Sign toolbox with his logical principles. Aristotelian logic is no longer concerned with the essence of things, but with elaborating fundamental tools of thought. Whatever is conceived here is fed by the phantasm of the pure and unadulterated letter. Whether Aristotle invokes the consistency of letters (that A cannot be both true and not true at the same time, the law of contradiction), whether he allows letters to oscillate between true and not true (in the law of the excluded middle), or whether he invokes the law of identity (A=A) – all these axioms go back to the axiom of the pure letter.33 In the literal sense, Aristotelian logic is A-logic from the outset because the Letter is the axiom of axioms. Of course, because according to the formula that states the efficacy of the Sign lies not only in what it says but also in what it doesn’t say, this axiom already contains an omission. And with good reason. For if the prehistory were present in memory, the acrobats of logic would plunge into the labyrinth of Signs, where Alphabeast lurks instead of pure ideality.

How to Philosophize with a Hammer

Socrates' philosophy of language can be viewed as an early form of media theory, as he compares the process of word formation to the art of blacksmithing, continually returning to the tool's reference.34 Naturally, one of the tool’s fundamental images is that of the hammer. As an extension of the hand, as an exteriorization and reinforcement of an already inherent power, it seems to be a part of the body that is an organon turned outward.35 The unity of tool and hand suggests complete control, acting in full possession of the user's powers, reinforced by an Iron Hand. Any philosophy using the tool concept as such—and this includes the various »media discourses«36—is essentially philosophizing with a hammer. Now, the essence of the Alphabetic Sign consists not only in what it says, but also in what it conceals. However, this concealment aspect doesn't become evident when bringing your philosophical hammer to bear. Even the Lost Form’s casting process is of much greater complexity than the medium suggests, for this technique is based on exclusion, or, if you will, on the abstraction of the human hand. The ingenuity of this process lies not in human power but in the knowledge of the material and sequencing of its production steps, shifting the very conception of the tool to knowledge, and in how the metallurgist puts his material to work. In this sense, the process's intellectual nature becomes wonderfully clear in its form, which dissolves, having fulfilled its function. A reflexion of the Lost Form is articulated in its mechane, reflecting its double reality: the Machine, which follows a specific function on one side. At the same time, it also acts as a deception of nature on the other. This dual purpose can be described if the Alphabet is understood as a symbolically structured Machine. While it functions as a notation instrument capable of recording everything (even that which doesn’t exist), its other purpose is opening up a virtual metaphysical space for the Alphabeast’s liquidation. It is no accident that fantasies sparked by Writing open up a totality of what is accessible: depending on the context, meaning the World, Nature, Creation—which later gets summed up as machina mundi: World Machine. This claim to totality, however, makes clear that the idea of the tool as something at hand, functioning like a hammer, falls far short of the mark. The Alphabet is not to be understood as a Tool, but as a Workshop. This Workshop, in turn, is symbolic—pretty much what we today call a virtual space. In this sense, the Labyrinth's image strikes at the matter’s heart. As a closed, artificial space, it marks the exclusion of the World while also assuming a spatial dimension. It's now evident how inappropriate the Tool’s conception is when discussing a space. I don’t have control over this space; I am part of it. Yet it is precisely this relationship that gets ignored whenever Writing is conceived as a tool or medium. The reason this occurs is quite banal. To dominate Writing means taking possession of its creative power, without making the sacrifice of abstraction that Writing demands. This sacrificial deception persists, as it were, in the Tool’s conception. Naturally, this sacrificial deception, which reaches its highest form in the fantasy of self-creation and hubris, comes at the cost of relativizing, repressing, and separating off all the tributes that must be paid to Writing.

Placing this split-off sphere of written religion in a structural relationship with the ancient fertility religions, we can say that the place of shame is no longer occupied by infertility, but by illiteracy. Assuming this, the ability to write acquires a different significance. If Roland Barthes once said that »desire writes the text,« then it could be argued that Writing and the ability to write structure desire. Thus, by putting letters together to form words, I may indulge in the illusion that I have mastered my ›typewriter‹, but insofar as the logic of this process eludes my thinking, this means something inscribes this act in the unconscious: the desire to participate in the world of Pure Signs, the desire not to be who I am. 37But precisely, this desire amounts to an exclusion of everything that could contaminate this space, which marks an ascetic energy—an energy finding its perfect expression in the great non-signifiers, the genderless angels of Christianity. If the medium assumes that I write (that I could be the master conqueror of Writing), then the workshop says that, like the Minotaur, I’m stuck in the cage [Zwinger]. Written by writing, conquered by compulsion.

The Serving Grave

The Alphabeast's death has left an empty space, a kind of cenotaph behind. However, this grave, in which the Cretan bull god's sekretum enters into the Alphabetic Sign, becomes fertile again: for here the promise of artificial life comes into force. Strictly speaking, therefore, the Alphabeast isn't dead, but has merely changed its form. If the Minotaur must die, it is so that it can be brought back to life anywhere, anytime, anyhow—precisely where the Signs are made to dance. As they said in ancient times, we're dealing with a serving grave, a hollow form giving birth.38 In fact, the Sign's emptiness is the prerequisite for its fullness. Only when the Sign is nothing, because no trace of reality clings to it, can it become the universal equivalent, the substitute for any body.39 Writing, as a Monument to Things, takes the place of the World, and it can do so because it’s inherently an absolute tautology (A=A, the promise of metaphysics). The God of philosophers establishes himself in the Sign of the pure, tautological Sign, which has relieved itself of its body. This God is not only an abstract entity but also (insofar as he's absorbed the mind of the Minotaur) fertile himself. Of course, the fertility of the logos spermatikos should be thought of less in terms of nature than in the manner of the Cretan metallurgists: a kind of magma, a glowing substance from which, in a most miraculous way, the forms and formulas of thought spring forth. The Alphabet thus marks something like a symbolic conflagration of the world, a profound transformation. Just as molten bronze annihilates the body, this negation is accompanied by the idea and mastery of a prima materia. Similarly, the Alphabetical Sign annihilates the worldliness inherent in the Body of the Sign. If we try to imagine the early stages of this thinking, we can not envision this process as hot enough. This isn't a cool Sign operation; au contraire: here, the magma40 is bubbling, the cauldron of magmafication from which Western Philosophy forms its syllogistic tools: Identity, Causality, the doctrine of the excluded middle, and the like. However, and this is where the hermeneutic difficulty of this process lies, there is no way back from all these cold structures. These products conceal their passage through fire. Only by examining the myth's dark images can we begin to grasp the powerful violence [Gewalt] of this process – a power which, incidentally, even when obscured, constitutes the actual driving force [Bewegkraft] of thought. This power is most clearly evident in Greek Natural Philosophy, which was dedicated to searching for the World’s universal formula. When Heraclitus writes: »Fire turns into the universe and the universe into fire, just as gold turns into coins and coins into gold«41 – the awareness of semantic meltdown remains. Only two centuries later, Aristotle will write in his Metaphysics that »natural philosophy is a kind of wisdom, «42 but it’s preceded by logic. With this dictum, Aristotelian A-logic decouples itself from the condition of its possibility.

Added Value

Heraclitus' equation, which has the spirit of fire and the All-One on one side, surprisingly brings coins into play on the other side. Although this may initially serve to merely illustrate the idea, it should be kept in mind that the appearance of the coin immediately follows the Greek Alphabet, and around 650 BC, coins that were mass-produced and stamped with their face value began to circulate. Considering that money in the form of temple money was originally intertwined with the religious sphere, the circulation of these coins alone marks a significant turning point corresponding precisely to the change brought about by the Alphabet. Just as the Aleph with the Sign of the Bull removes the obligation to pay tribute to animal forces, so too does the coin also lose its sacred character. In doing so, however, it reveals itself as the counterpart to the Alphabetical Type.

The fact that a coin can be taken at face value is itself a remarkable process: A process describing the intrusion of the concrete abstract into reality. This process assumes the existence of the Alphabetical letter, which in Greek also functioned as a numerical Sign. Because the elementary lesson of the Alphabet lies in how each Sign can only be taken at face value, and it would make no sense to decipher the body of the Sign—in other words, recognizing the shape of a bull in alpha or a female breast in beta. In the same way, those taking the coin at face value ignore the Sign's respective body, which is precisely where the volatility and transferability of the Sign lie. The coin in circulation is always meant figuratively, therefore metaphorically, which is always assumed when speaking of a medium of exchange. If, on the other hand, we imagine replacing the metaphorical body with the concrete coin itself, we'd immediately encounter the same resistance children show when they cling unwaveringly to the shiny coin despite its face value and all the persuasion in the world. This childlike belief doesn’t seem entirely unfounded (after all, casting was also referred to as ars fingendi), and even the act of merely naming something at face value isn’t sufficient guarantee of the coin’s quality and validity. Thus, the coin reveals the inscrutability of the pure Sign43, for here we are dealing within that sphere where the mere face value must be taken as true, not as an airy sign thing, but in its materialized form: as the Body of the Signs—a body that must be universally accepted and capable of being traded.

Nevertheless, when such a type of coin appeared in the 7th century BC, the most remarkable thing was how this entity had removed itself from the realm of religion to such an extent that in Crete, coins can be decorated with images of the Labyrinth and the Minotaur. In the Heraclitean analogy, the coin's appearance signifies that the right of coinage (and thus sovereignty, not only over the Sign system but also over the act of creation) is interpreted as belonging to this World, revealing the grave’s function as a place of service. We're dealing with a symbolic death and, at the same time, the promise of a symbolic life. In this sense, the semantic meltdown turning gold into coins and the Bull into the Alpha marks the Holocaust of the Greek pantheon. With the myth of the Minotaur, and with the founding act of Cadmus, Greek culture expels from itself what it will henceforth call barbarism: that pantheon of gods beholden to the potency of animal power [Tierkraft].

Nevertheless, when such a type of coin appeared in the 7th century BC, the most remarkable thing was how this entity had removed itself from the realm of religion to such an extent that it could be decorated with images of the Labyrinth and the Minotaur in Crete. In the Heraclitean analogy, the coin's appearance signifies that the right of coinage (and thus sovereignty, not only over the Sign system but also over the act of creation) is interpreted as belonging to this World, revealing the grave’s function as a place of service. We're dealing with a symbolic death and, at the same time, the promise of a symbolic life. In this sense, the semantic meltdown turning gold into coins and the Bull into the Alpha marks the Holocaust of the Greek pantheon. With the myth of the Minotaur, and with the founding act of Cadmus, Greek culture expels from itself what it will henceforth call barbarism: that pantheon of gods beholden to the potency of animal power [Tierkraft].

You only have to read how precisely and with almost ethnographic detachment Herodotus describes the Egyptian bull sacrifice44 to appreciate the deep chasm that opened up between the Greeks and the barbarians. The barbarians will be those who worship occult customs. We could say: with the Alphabet as the flight of metaphysics, Greek culture rises above nature in the same way that Crete sought to leap over the Bull. If we consider the Metaphysical Philosophers as mental acrobats, it seems as if this leap beyond sacrifice has actually been achieved, as if thought has freed itself by its own power, soaring toward the sky, toward an empty and blue sky…however, as the coin shows (which is itself a collective construct of belief), the obligation to pay tribute has merely shifted—in the sense that now the Sign System’s integrity must be maintained. This is the point that compelled these thinkers to make this sacrifice to the Philologists' God. Just as meticulously as the Egyptian priest examined the purity of the sacrificial bull, so too in the Scriptural God’s temple of the Written Word were symbolic sacrifices carefully examined for purity. In this sense, the mental acrobats' trick of transcendence is to effectively bypass the taboo by leaping over it, which not only devalues their sacrifice but also tears asunder the cohesion established by the Sign. At this point, the deep aversion of Greek Philosophy to nothingness becomes understandable in all of its clarity. This vacuous Nothingness, which cannot be—marks not merely an intellectual gap, but also the symbolon's diabolon. The diabolical nature of this nullity of the Sign lies in that, insofar as the symbolon is self-made, the diabolon would no longer fall back on an external tempter, but on the maker himself.45 In other words, to look inside the tomb wouldn't be encountering the bliss of beholding the naked supernatural Logos—it would be looking at yourself: staring into your own phantasm, in a diabolical form.

Shared Reading

Wherever »nature« purified by the gods comes into play, we’re not dealing with nature, but with the Book of Nature, which essentially means plastic. And since the zoon politikon also belongs to this »Nature«, social space doesn't appear to be natural but a social, transformable plastic [Kunststoff]. One way of structuring this space is through law. Legislation, in turn, is an act that has its prototype in Writing. If Cadmus is celebrated not only as the bringer of the Alphabet, but also as the founder of the first Polis – the only one, incidentally, whose mentioned by name – this parallelism proves that both spheres are always encompassed in the Nomos. City and Writing, Lex and Lexicon, Orthodoxy and Orthography are inseparably linked. The revolution of the Signs goes hand in hand with a revolution of Society, and this is precisely what defines Greek culture.46 So it's therefore no coincidence, nor an internal inevitability, that the »invention« of the Alphabet cannot be attributed to a single genius—but instead, it dates back to myth, to a time when a new order dawned in the night sky of thought. As Europa's migration of symbols tells us, we're dealing with a cross-generational, collective process that only experiences its apotheosis in the marriage of Kadmos and Harmonia. And if the symbol is based on the act of symballein – as the communal throwing together – which in turn goes back to the communal sacrificial feast, then it stands to reason that the collective sacrificial deception which culminates in the Alphabet symbol also amounts to such a throwing together. What’s remarkable here is how the concept of the collective already presupposes such a communal reading. The Greek legein means to gather, select, distinguish, say, read, count – and from this, it can be concluded that the collective is already the fruit of a communal reading, a com-legare, a collegial, collective discipline.47

If Writing, or more precisely, the symbolic body of the communal legein, represents the community-forming moment, then the Sign operations must have their reflexion in the collective structure. Putting it bluntly: the individual's image must correspond to the Alphabetical Type. And indeed, it is obvious to read Greek democracy against the backdrop of homogeneous Signs. Thinking from the Sign also lends credence to that strange, antinomic double meaning that interprets the citizen of the Polis both as a freely moving individual and as a collective existence brought into conformity (which would be the Spartan variant). Given this interdependence, the antinomies familiar to us of individual versus society must seem inappropriate. The Greek Hoplite order exemplifies how the logic of types is inscribed into society. This army formation represents a novelty that sets the Greeks apart from the »barbarians« in military terms, just as the Alphabet and coinage do.48 While duels prevailed in the archaic times of Homer’s heroic sagas, the Hoplites marched in lockstep in closed formations armed with bronze breastplates, greaves, helmets, and wooden shields. Most importantly, the shield held by the Hoplite didn’t protect just his own body but that of the man next to him.

If you imagine the injuries caused by the enemy's spear – above or below the shield, where the neck and genitals are located – it's not difficult to envision that, in this order, charity and brotherly love become a commandment of self-love. Such a Hoplite army is a collective entity, pulsating with an ethos that Murray calls »the duty of the individual to the state.«49 Of course, this explanation doesn't shed light on what motivates the individual to voluntarily enter into such an arrangement in which the instinct for self-defense is subordinated to collective striking power and discipline. 50How is something like this possible? Invoking the State hardly helps here. As a rule, this only leads to a game of metonymies, a tautological chain in which one riddle word is answered with another: the State with patriotism, the sense of community with ethos, or vice versa. But what is the State? And are we not dealing with a new structure that has never existed in this form before?

More promising, in my view, is the reference back to the symbolic order that (as the myth of Cadmus tells us) accompanied the founding of the Polis. In fact, the novelty of the Hoplite order would be more plausibly explained by considering the figures of thought developed in the Alphabet as ideals of Body and Personality. Because the homogeneous Sign always also implies HOMO-GEN, the Hoplite formation demands that each individual perform a similar act of homogenization. While relativizing his intrinsic value, it also promises him a higher harmonious existence in the Social Body [Körperschaft]. Seen in this light, the reference to the State makes sense again, namely as the highest conceivable stasis, as a system of Signs and Order in which all parts of life (procreation, education, everything considered to be discipline and order) converge. Assuming this is a collective community reading, it becomes understandable how such a structure, which robs the individual of his nobility and uniqueness, is possible. If this male alliance (whose faint reflexion can be found in Men's Choral Societies of Harmonia) has the power to impose such a narcissistic affront on the individual as nothing less than virtual castration, it is only because participation in collective existence means participation in the phantasm. Conversely, this participation also means that individuals are relieved of specific precariously tricky questions so that their concerns can be delegated to the collective and disposed of. Therefore, taking your place in the Alphabetical order means: the ability to effortlessly leap over the bull. The Greek Hoplite order does not stand for itself, but as an exemplar of the literate society's constitution of the subject, which requires each member to learn the ABCs. This act of discipline represents a loss: the loss of childhood, if you will. Nevertheless, this incorporation also offers compensation as the Alpha type with its writing, enabling the imagination to break free from this group discipline. It is the freedom of the blank space: to stand above things, to be unchangeable, to participate in a higher identity, I AM THAT I AM.

Like many of the pre-literate cultural heroes, Minos is thought of as a collective figure. Minos is therefore the title of the Cretan priest-king genealogy that ruled Crete from 2500 to 1500 BC.

In the Idaean Cave, believed to be the birthplace of Zeus, bronze weapons are consecrated with bloody sacrifices. According to tradition, Minos visited the cave every eight years to consult with his father, Zeus, and renew his royal power. See Werner Burkert – Griechische Religion der archaischen und klassischen Epoche [Greek Religion in the Archaic and Classical Periods], pp. 56-57.

See Eliade, M. – History of Religious Ideas: From the Stone Age to the Eleusinian Mysteries: vol. 1, trans. W.R. Trask, Chicago, 1978, p. 134.

Occasionally, it is also said that Minos, bewitched by his jealous wife, killed his many lovers with snakes, scorpions, and centipedes. See Pseudo-Apollodorus – Library III, trans. J.G. Frazer, Cambridge, 1921, [note I] xv-2, p.105.

In Homer, Minos appears as a venerable, just ruler who holds a golden scepter in his hand and consults with Zeus. Plato, in particular, portrays him as a cultural hero of almost Mosaic proportions. This other part of the tradition, which cannot be reconciled with the image of the tyrant, depicts Minos as a conflicted figure, a symbol of a broken order.

»But the shame of the house grew: people recognized the mother's beastly deed / Horror in the child's monstrous double form. / Minos is determined to remove this stain from his marriage: he wants to lock him / In a hidden building with dark, winding passages. « See Ovid – Metamorphosen, Book 8, v. 155 ff.

In depictions from Crete, priests can be seen wearing bull masks.

See Plato – Menon, chapter 39. In Menon, Euthydemos, Kratlyos, trans. Friedrich Schleiermacher, Munich, 1974, 97d.

See Françoise Ducroux – Der Künstler, Meister des Lebens und des Sehens [The Artist, Master of Life and Vision]. In: Daedalus. Die Erfindung der Gegenwart, [The Invention of the Present], eds. Gerhard Fischer, Klemens Gruber, Nora Martin, Werner Rappel, Basel/Frankfurt/M. 1990, p. 33 ff.

The context in which Daedalus' steles appear in Socrates/Plato is highly illuminating, as Plato neatly separates the two aggregate states of these artifacts. They possess value as bound, tangible, and fixed artifacts, but not where they lead eerie, uncanny lives of their own. »SOCRATES: So, to possess one of his works that has been let go is not particularly valuable, just like a vagrant, for it does not remain; but a bound work is very valuable, for they are beautiful works. Why is this about, then? It is about correct ideas. (...) And that is why knowledge is to be valued more highly than correct ideas, and it is precisely the fact of being bound that distinguishes knowledge from correct ideas.« See Plato – Menon, chapter 39. In Menon, Euthydemos, Kratlyos, trans. Friedrich Schleiermacher, Munich, 1974, Book VIII, v. 233.

Ovid – Metamorphosen, trans. Hermann Breitenbach, Stuttgart 1971, Book 8, v. 233.

»As he arches the hill, he sees him / From the muddy swamp, the chattering partridge: there he bobs / With his plumage, he lets his joy be recognized by his song, / At that time a unique animal, unknown in earlier times, / Recently becoming a bird, eternal shame on you, Daedalus!« See Ovid – Metamorphosen, Book 8, v. 236 ff.

The circle, called Kerkel in ancient Egypt, traces to the two Indo-European roots Ker and Kel. Ker means: to throw forward, and from this comes kara – the head (Karas Horn, karymbos highest point. And Greek korone – the crown, which refers to the one who arranges everything, to humans, the crown of creation. Krikos, kirkos (church), kyklos, krypta. The skull. Kel means »to hide« and pointing to the hidden. Cella – cell, cellar. This is the space in which I hide, but it is also the helmet under which I conceal my head, the hidden, the shell, the cave: The shelter. The etymology of Kerkel, Zirkel [circle] can be read as a prefiguration of the image that becomes essential to the Daedalus story: the Minotaur in the labyrinth—the fertile cave of thought, the mind's catacomb, the head's inner space.

However, this attribution is already based on the recoding that the labyrinth underwent through the legendary labyrinth of Daedalus. As an autological space, the labyrinth already appears as a prototype of modern spaces, which is why we speak of the first geometrical space, or algorithm. (See Pierre Rosenstiehl: »Geometer Daedalus.« In: Daedalus. Die Erfindung der Gegenwart, [The Invention of the Present], eds. Gerhard Fischer, Klemens Gruber, Nora Martin, Werner Rappel, Basel/Frankfurt/M. 1990, p. 26). The intensity of this logical form's echo is evident in how medieval cathedral architects chose the labyrinth as a symbol of their own creativity, which they depicted in church interiors.

See Werner Burkert – Griechische Religion der archaischen und klassischen Epoche [Greek Religion in the Archaic and Classical Periods],Cologne/Mainz 1977, [Note 80] p 56.

See Calasso, R. The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmonia, [Note 32], p. 76.

The connection with Dionysus becomes much more plausible when considering that both figures belong to the same problem area: a reproductive order that’s broken away from conventional forms and, instead, with the twice-born god, already follows the Promethean phantasm.

The phantasm of artificial life pervades all layers and side strands of the myth. One of Ariadne's brothers is Glaucus. It is said that Glaucus fell into a barrel of honey as a child and died. Minos calls upon a soothsayer, Polyidus, for assistance. He is locked in a cave with the corpse and instructed to revive him. In this womb-like situation, a snake approaches the honey barrel, and Polyidus, the soothsayer, kills it. A second snake approaches, and Polyidus observes how it touches the first snake with a leaf and brings it back to life. Polyidus, the all-seeing, can revive Glaucus, who suffocated in the honey, with this leaf. One interpreter has interpreted this myth, quite plausibly, as a secret teaching of metallurgists. See Braune, A. – Menes - Moses - Minos: Die Altpalastzeit auf Kreta und ihre geschichtlichen Ursprünge. Essen 1988, p. 125 ff.

In its fundamental differences, this culture was already a mystery to the »barbaric« contemporaries of the Greeks. Herodotus recounts the bewilderment of Persian historians, who were utterly ignorant of the Greek tendency to go to war for the sake of a woman: »Their [the Persians'] opinion is that stealing women is the business of unjust men, seeking revenge for those who have been stolen is the business of the ignorant, and not caring about those who have been stolen is the business of the wise; for obviously they would not be stolen if they did not want to be.« See Herodotus – Historien, translated by Eberhard Richsteig, München 1961, Book I, Chapt. 4.

To anticipate an objection, it is certainly undisputed that the development of writing systems in the second millennium shows a clear tendency toward phonetic notation. This argument seems to relativize the special position accorded to the Alphabet here. However, there is an essential difference, one that also applies to the metallurgical innovation of the lost form casting technique. The Alphabet marks the final stage in which the Sign is nothing more than sound. In a closed system, there’s no longer any impact from outside. The Alphabet has thus become self-sufficient. Only through this process does the illusion of autology arise; that is, an inherent power [eine inhärente Kraft] that becomes fertile in its own right.

See Burckhardt, M. – Metamorphosen von Raum und Zeit: Eine Geschichte der Wahrnehmung, Frankfurt/M, 1994.

The extent to which the circle dominated Greek thinking becomes clear when considering that even the trajectory of an arrow was regarded as a composite of circular movements.

The Aristotelian concept of entelechy, which posits that matter articulates itself according to the form inherent in the seed, also follows this pattern.

Novalis once said that the »highest book« is like »an ABC book.« See Novalis Werke, ed. Paul Kluckhohn and Richard Samuel. Darmstadt 1960 ff., vol. II, p. 610.

»The first [harmonious] combination, the one in the center of the sphere, is called ›hearth‹.« See Philolaos' Writings, in: Die Vorsokratiker, edited and translated by Jaap Mansfeld. Stuttgart 1986, vol. I, p. 153.

Heraclitus, frag. 46, in: Die Vorsokratiker, edited and translated by Jaap Mansfeld. Stuttgart 1986, vol. I, p. 259. – It's interesting to see that Heraclitus has a unique sense for the hidden nature, or the abstraction of this process. Not only does he claim that nature tends to keep itself hidden, but he also links his sacred fire with the figure of Zeus, in the monotheistic sense as conceived by Wilamowitz-Moellendorf: »The one thing that is, is not ready and yet ready to be named Zeus.« (See Die Vorsokratiker, edited and translated by Jaap Mansfeld. Stuttgart 1986, vol. I, p. 257.)

See Plato – Menon, chapter 39. In Menon, Euthydemos, Kratlyos, trans. Friedrich Schleiermacher, Munich, 1974, 97d.

See Plato – Kratylos, trans. Friedrich Schleiermacher, Munich, 1964, p. 120.

See Plato – Kratylos, trans. Friedrich Schleiermacher, Munich, 1964, p.149.

»(...) The letter R, as I say, seemed to the person who established the naming system to be a beautiful organ for movement, as it itself represents movement through its agility; hence, it is used very frequently for this purpose. First of all, it represents movement in streams and currents; likewise in defiance and in roughness, and in all such verbs as to rattle, to rub, to tear, to smash, to crumble, to turn.« SeePlato – Kratylos, trans. Friedrich Schleiermacher, Munich, 1964, pp. 152-153.

»Now that we have become familiar with all of these, we must understand how to bring them together and relate them to one another according to their similarities, whether it be one to one or several mixed together to form one, like painters who, when they want to depict something, sometimes apply purple alone and at other times another color, but then mix many colors together, when they prepare flesh color, for example, or something else of that kind, depending, I think, on what each image requires of each coloring agent. So too, let us apply the letters to things, sometimes one to one, when we deem it necessary, sometimes several together, forming what are called syllables, and then combining syllables to form words, nouns and verbs, and finally we want to form something great, beautiful and whole, as there the painting is to the art of painting, so here the sentence or speech is to the art of language or speech, or whatever the art may be called.« See Plato – Kratylos, trans. Friedrich Schleiermacher, Munich, 1964, p. 151.

If Socrates, this non-writing philosopher, is also considered one of the great critics of writing who subordinates the dead letters of spoken language, there is no contradiction in this. For what’s at stake here is the existence—ideally attested to by the letter—of a metaphysical being that can only articulate itself in the world in a corrupted form. Instead, the powerful concept from the Book of Nature comes into play here, which cannot be pressed onto papyrus scrolls or book covers. The body itself becomes the sytlos. SOCRATES »(...) For some say that bodies are the graves of the soul, as if it were buried in them for the present time. And again, because through it the soul makes everything comprehensible that it wants to indicate, it is also rightly called, as it were, a gripper or stylus.« See Plato – Kratylos, trans. Friedrich Schleiermacher, Munich, 1964, p. 122.

This World, in quotation marks, is inconceivable in a writing system such as Chinese (and so it's perhaps no coincidence that China had to wait until the nineteenth century of our calendar before someone took pity on its people and wrote the first Chinese grammar book).

See Plato –Kratylos, trans. Friedrich Schleiermacher, Munich, 1964, p. 109.

This idea of exteriorization (which always conceals an idea of evolution) is, so to speak, a leitmotif of historical anthropology. See André Leroi-Gourhan – Gesture and Speech, Cambridge, 1993.

Even though the term medium is a sober, functional description of the tool’s conception, it extends the idea of the tool by interpreting the medium as an intermediary for a purpose. The medium, therefore, presupposes that those who use it have control over it.

In the contemporary version, which differs in that the realm of letters has been replaced by electromagnetic writing, a cursory study of pornographic productions reveals that there isn’t a film that doesn’t operate with the artificial eye of the camera.

A detail of the Oedipus tragedy is striking here, namely that Oedipus leaves no burial place behind. This intellectual aspect has always been overlooked in Freud's infantilization of Oedipus. Not only does Oedipus free the Thebans from the Sphinx’s reign of terror by solving her riddle (thus inaugurating the Gnostic project: Recognize that you are a human being), but this journey of self-knowledge also continues when it comes to uncovering the crime. Thus Oedipus hurls at Tiresias that he should strike him »by the mind,« and not »by the flight of birds« (Sophocles – König Ödipus. In Tragödien, trans. by J. J. Ch. Donner. Munich 1970, v. 399.) This slight shift, which replaces the flight of birds with the flight of thought, reveals Oedipus's tragedy as an intellectual tragedy. The story of Oedipus doesn't end with his blinding. In Oedipus at Colonus, Sophocles paints the picture of a purified sage. Oedipus flees from the pursuit of his heirs to the throne, who’ve driven him out of Thebes, to Theseus, who grants him exile. Ultimately, Theseus, the bull-slayer, accompanies the wise and just man to a sacred grove. Oedipus dies without a grave: »But tell no man where my bones lie hidden, nor in what place they rest. / And it will be a stronger protection for you all / than a shield and many mercenaries against your neighbors.« (Oedipus at Colonus, v. 1552 f.) When Oedipus' daughters, Antigone and Ismene, wish to see their father's grave, Theseus refuses them, stating that »no mortal may approach that place.« Because Oedipus' grave remains unknown, it can become a monument to the collective. According to the Socratic formula that one makes one's own body the stylus of the soul, the gravestone-less Oedipus becomes a kind of suggestion box into which the community writes everything individuals cannot articulate about themselves.