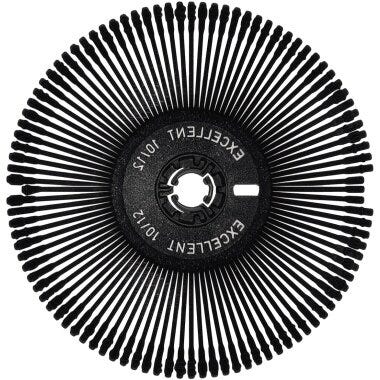

I don't know where the power that Writing has exerted on me comes from. It may be that the Holy Scriptures, the world of prophets and revelations have played their part. But because I don't really believe in holiness and also doubt there’s such a thing as a born author, this fascination must go back to my childhood. I do remember my Father giving me a typewriter before I even started school. I don't know what prompted him to do so. Perhaps it had something to do with that I’d taught myself to read - in any case, I was suddenly the proud owner of an old Olympia typewriter. Now, because it was already a bit old, certain keys would get caught in each other - whereupon they had to be carefully released from their entanglement. This was probably the reason it came into my possession as my father from then on typed his sermons on a more modern machine - but it didn't dampen my pride in this extension of myself; indeed, it was my plan that I would now write a book myself. And to copy the format of my Enid Blyton children's books, I divided the A4 page in half and spent a good six months thinking up the story to go with it. At some point, somewhere between 180 to 190 pages had come together - and the idea of a book was no longer a foreign continent to me.

If you immerse yourself in the great works of world literature, the idea that you can easily become a great writer recedes into the distance. Instead, you realize the subtleties of writing - and fall under the spell of fiction production, that great seduction that's been the lifeblood of all writing since Don Quixote. One has one's head in the clouds - or more precisely: you breathe the air between the lines and realizing this ethereal world eclipses everything the material letter presents. That’s why what the critics called Bovaryism (the life that becomes a novel) is the precondition of all authorship. It's no coincidence that when Gustave Flaubert was accused of violating religious morality and good manners, argued in his defense: he was none other than Madame Bovary, except that this whore would outlive him and he'd die like a dog (‘Cette pute de Bovary va vivre et moi je vais mourir comme un chien.’). Nevertheless, the question is: what happens when the letter changes? What if the letters, as in my decrepit typewriter, begin to interlock?

Basically, the emergence of what I've called electromagnetic writing (which has entered a state of complete liquefaction with digitization) marks a profound change in what can be considered writing. What is writing isn't limited to the world of letters anymore but encompasses everything that can be digitized. It was precisely this explosion that initially disturbed and then electrified me as a young writer - because it brought fantasies into play that'd previously been completely unimaginable. In retrospect, my juvenile great writer megalomania looked like a form of adolescent aberration, but the disappointment stopped. What was more rewarding was this realization that the position of writing had changed: in place of the ruler who'd command his of letters like a general over his troops, a form of authorship had emerged in which patient listening was far more important than dictation. And so the discoveries of the wonderful sounds felt far more gratifying than any gesture of domination of a paper world brought into life by ordre de mufti. If the recording studio had made me familiar with the position of being a receiver, this also changed my relationship to the words. For they no longer seemed to me like docile instruments but became like ambassadors from another world, voices emerging from the unconscious - awakening forgotten, repressed worlds. And because this continent was a foreign one, from then on, I began each day by copying a paragraph from Dornseiff's German vocabulary or delving into the etymology of some random word. If there was one result of this retreat, it was that I began trusting the language to such an extent that writing sometimes felt like a form of ID SPEAKS, an écritue mecanique, where I had to do nothing more than make the words sound.

The experience that etymology opens up a foreign world, even a mental unconscious, was an insight that's also served as a guide when returning to forgotten zones of cultural history. Basically, it was linked to nothing more than a willingness to abandon supposed certainties in the face of an unexpected encounters. And just as the words had taken me into strange spaces ('The longer you look at a word, the stranger it looks back'), one blue wonder followed the next. One exemplary: Because I'd read that a certain Nicole Oresme, Bishop of Lisieux, had delighted his contemporaries with a proof of God (in which the good Lord was unceremoniously retrained as a watchmaker), my curiosity was piqued to find out more about this 14th century scholastic, all the more so because the histories of philosophy had ominously characterized him as a 'pre-Cartesian.' But when I began studying his writings, a moment of confusion set in. Because alongside his proof of God's existence was a treatise on the devaluation of money and next to it lay a work entitled De Proportionibus Proportionum – which contained a series of mathematical sketches. Strangely enough, they were all uniform triangles which led to a puzzling question about the purpose of these representations. Eventually, a redeeming thought occurred to me. If this Scholastic writer answered one proportion (let's say: 1:2) with another proportion (2:4, or 3:6, or 4:8), it was because he was in a world before zero, and it was impossible for him to notate this quantity as a number: as 0.5. Nevertheless, all the uniform triangles were pursuing the goal of making this representative, as Oresme called his desired figure, tangible. Oresme's triangles were nothing more than an attempt to approach the zero position via triangulation, and I realized that the zero had been invented so that geometrical bodies could be scaled independently of their length. This meant that the zero could be understood as a machine for creating geometric solids.

Because I had gotten into the habit of doing a little etymological research on every word arousing my curiosity, at some point, this word appeared before my inner eye: mechané. That the Greeks, who had coined it, first and foremost used it to describe ‘trickery,' or even the ‘deception of nature' (and this before any use of a material machine), seemed quite understandable to me - far more plausible than the unreasonable proposal that, as suggested by deus ex machina, the machine world should be understood as a mere theatrical coup. Nevertheless, the question remained how such a worldly interpretation could have come about in the first place. After all, the Indo-European *magh, from which mechané is derived, refers to magic in the broadest sense, just as it refers to might - and these were always higher powers, demons, and spirits. This was precisely the moment when the image of a typewheel appeared before my inner eye - and with it, the thought that the alphabet could be understood as the first machine, as the moment when a belief in miracles in primitive cultures was replaced by reason, the deception of nature.

That the machine is not a device but a system of writing was an intuition that went hand in hand with everything I'd experienced first-hand in the recording studio when working on the spoken word. In 1993, when the Internet was still in its infancy, answering such a question meant going to the State Library. Consequently, one day, I found myself there, more precisely: standing in the dusty parking lot between the Philharmonic and the St. Mathew church. Because my search had been successful, I was holding a book bearing the title Sign and Design, which promised to shed light on the psychogenetic sources of the Alphabet. But what I saw before my eyes as I pulled the car keys out of my pocket gave me pause - it practically put me in a state of forgetting the world around me..

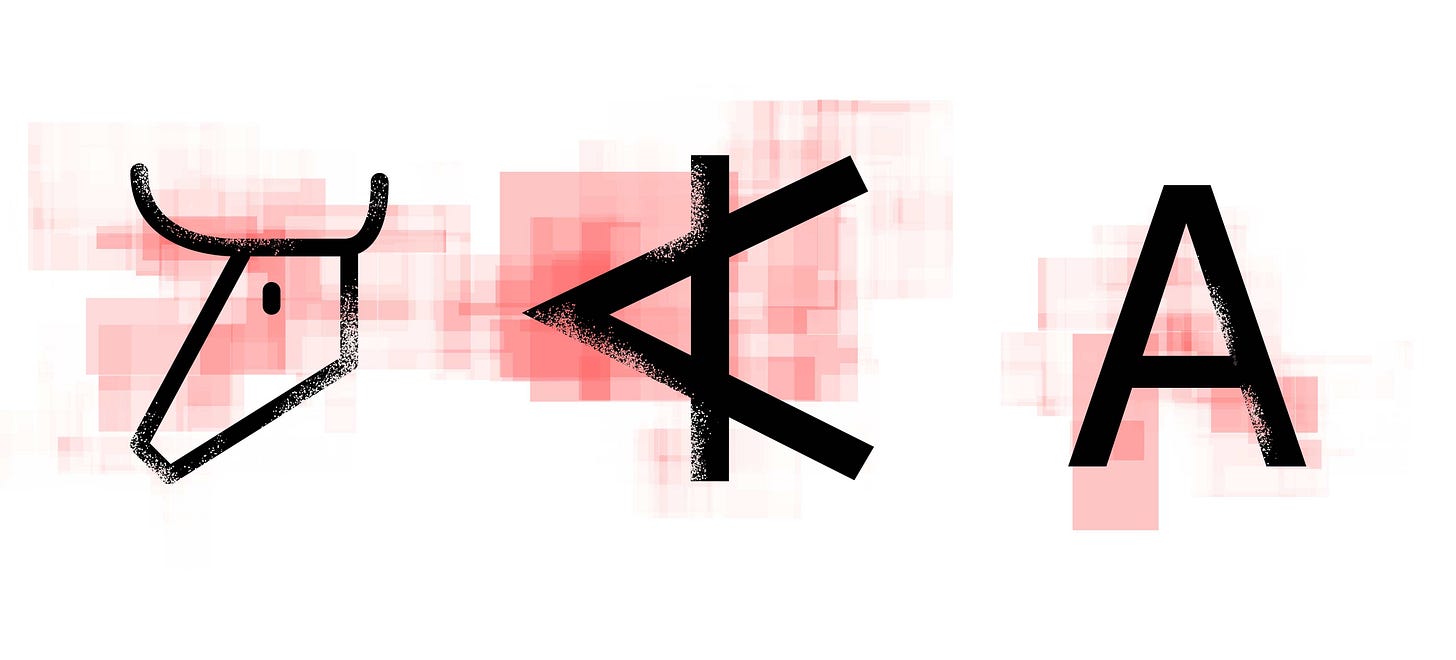

The first thing that caught my eye was a series of illustrations. One showed the image of a bull. At first, it seemed pointless to me, but then I realized this bull sign was nothing more than an upside-down capital A. And when I saw that there was another A next to it - except it was rotated by 90°, I understood that the revolution of signs wasn't just a headline, but reflected the history of the sign itself. However, even more powerful than this realization was the shock that, although I'd studied the philosophy and cultural history of signs, I'd never seen what a child could have seen: that the sign once referred to a living being - and it was at this moment that the state library behind me, with all of its thousands and thousands of books, rose up and flew away.

Perhaps there's no more convincing image than this: our writing itself represents an unconscious, a fertility order hidden so deeply within our cultural memory that we are no longer able to see its meaning. Nevertheless, this battery is there - and its charge pulsates through every thought so strongly that we impose a higher power on the phantasm of writing, even if it stems from our own desires: artificial intelligence. And perhaps this was the real meaning of my Father's gift: that you only understand a typewriter when its letters, weak with age, interlock.

Translation: Hopkins Stanley

Related

Éducation sentimentale V

If the Machine seemed as a kind of longing for me, it was because it marked the breakage of my genealogical chaining to the world of my fathers and forefathers: a whole seven generations of Pastors, interrupted only by a professor of English who'd written a textbook entitled

Éducation sentimentale IV

Who doesn't know it? That moment when the RECORD switch starts flashing, signaling the recording is in progress. And not infrequently, in a professional environment especially, this is accompanied by a moment of panic: knowing from now on, every lapse, every slip of the tongue will be recorded. Consequently, the voice begins to tremble, one hears how th…

Éducation sentimentale III

What does a child of pop culture do when suddenly, in the guise of fatherhood and teaching responsibilities, he finds himself in a role for which there is no script? It all began with a simple request: a radio editor asked if I would like to join him in a three-week intensive seminar at Berlin's Hochschule der Künste (University of the Arts) on familiar…

Éducation sentimentale II

Perhaps only in the distance does a historical event take on a metaphorical grandeur. Up close, Francis Fukuyama's end of history was little more than a flickering television image lost in the noise of screen pixels. In any case, dismantled there a few miles away, the fall of the Wall felt less like a final triumph of Western democracies than that of a …

Éducation sentimentale I

Actually, the question of my counterpart was exceedingly simple. How does one come up with such thoughts as set forth in the Philosophy of the Machine? And my reaction to it was: “Because at some point, at the end of the eighties, I took a different turn.” I can’t say that this chosen path was a decision. Rather, it was probably a form of gradually beco…