Who doesn't know it? That moment when the RECORD switch starts flashing, signaling the recording is in progress. And not infrequently, in a professional environment especially, this is accompanied by a moment of panic: knowing from now on, every lapse, every slip of the tongue will be recorded. Consequently, the voice begins to tremble, one hears how the speaker is pulsed with nervousness, and it is not infrequent for the lump in the throat to become larger and larger and to grow into a globus hystericus.

When my surgeon friend, when I met him, remarked, he was sitting on the right side of the knife — where one might think of the director, sitting there, elevated at that, on the other side of the glass pane, dominating the shooting situation. In truth, it was anything but pleasant. Rather, it seemed to me that all the young acting students who sat there, one by one, at the microphone, communicating with the "director" via the intercom and waiting for the red light to flare up, were undergoing some kind of symbolic execution. I'd seen it dozens of times: a young person entering the recording room — and asking me, the director, how I wanted the text, whether he should be the cowboy or the sensitive one. But then it doesn't take a minute. Because the red light flares, the put-on self-confidence collapses, only just a bundle of nerves sitting there, struggling with itself, the world, above all the director up there. And because I'd experienced this dozens of times before in this seminar, this time I'd resolved to take every moment of intimidation out of this game. Everyone would be able to read the text they'd chosen from a collection of texts, there wouldn't be any intervention or interruption — and the inevitable question "How was I?" would be followed by invitation to come up to the control room and listen to the result for yourself. What followed was an astonishingly uniform parade, during which you could see the acting students exasperations listening to their performance under the headphones — if they didn't indulge in wordy self-flagellation. And, of course, everyone asked to be allowed to do another take — a request, oddly enough, backed up by the argument: "That's not me!"

And because that wasn't new either, the question had crossed my mind about what would happen if everyone listened to their voice in its raw, natural state. To relieve the speaker of any form of responsibility, I'd come up with a completely idiotic text: a kind of instruction manual, which the students only got to see once they'd set themselves up in front of the microphone. On the table were paper and pencil — and the task was copying this text and reading along what they were writing, as in elementary school dictation (complete with period and comma): That's a Tex-t. Period. And again, the procedure: Come up to the control room, listen to it! What was surprising to me and my colleague, who I co-hosted this intensive seminar (running eight hours a day for three weeks), was the students' reaction: Because everyone listening to their spelling practice performance under headphones was deeply taken with their voices — you saw (were there'd previously been a form of physiognomic disgust) a form of being blissed out, even delighted, "although, admittedly, the text is completely idiotic."

In a curious way, this unexpected result marked the seminar's goal: that the students, with their regained voice, would be able to shake off the artificiality of the recording situation and be freed up for the real task at hand. What nonetheless preoccupied me was the moment of division, and even schizophrenia, that the students had displayed. Because where they'd been given all the freedom in the world (the choice of text, the manner of interpretation), they'd ended up with a defiant self-negation, whereas the dictation that'd relegated them back to a form of childish irresponsibility had been experienced like a liberation, in fact, a blissful finding of themselves. And during the weekend, I’d mulled over where this contradiction came from. Obviously, the situation's artificiality provided a massive stress factor — and this was true even for those who'd been doing the job for years. For example, the actor who had delivered a long text for me in the station's soundproof radio play studio emerged sweaty and physically exhausted. In effect, all the technical equipment evoked a feeling of being in a spaceship about to take off at any moment. So I thought about what it'd mean if the whole setting faded out as far as possible, so the person involved was the master of the situation in every moment. With this desideratum, the following experiment essentially relieved its setting out, and it was only a matter of convincing my partner Wolfgang Bauernfeind of its utility. As a long-time radio editor who'd also directed countless times himself, he was deeply familiar with the problem — but was nonetheless taken aback when I laid my plan out for him. "Let me recap," he finally said. "You want a room with nothing in it but a recording device. And then, then what?" The student's job, I laid out for him, would be to go into that room, press the RECORD PLAY button, and then speak something onto tape for ten minutes – anything. It could be a prepared text, an improvisation, or a stream of consciousness – but they should also have the option of sitting in silence in front of the microphone for the entire time. The only condition was my colleague, and I would listen to the results and present one or the other take to the group — which is why the whole thing could also be thought of as a form of time-delayed speech.

Finding a suitable room didn't take long: a small, sparse practice room that the musicians usually used. Next to the piano was an armchair and a small table where the tape recorder and microphone could be placed. Since I was busy in the studio continuing to record lyrics, I didn't hear anything about the recording process. The assistant escorted the respective candidate into the room — and sometime in the evening, I was handed three or four cassettes. When my colleague and I listened to the tapes the following day, we didn't have the slightest idea of what to expect. And in fact, each performance was unmistakably distinctive. There was someone who'd prepared a text but broke off after just a minute or two, apparently feeling complete absurdity, and then apologized profusely. A young woman talked about what she wanted to talk about but then said she was having terrible period pains and wasn't feeling well today. And finally, there was the angry young man who, after pressing the record button, remarked how moronic he thought this experiment was, but if we want to hear it, so be it. With this, he opened the piano and hammered away at the keys with his fist for twenty minutes. Curiously, each of these performances afforded a glimpse into the depths of the soul, indeed, was of a hypnotic intimacy in which even supposed failure was of a disarming sincerity — something reminiscent of the experiment with childhood noises we had conducted in a previous seminar. And although we had granted the possibility of silence, no one used it. On the contrary: it was precisely the invitation to refuse that resulted in the speakers carefully considering their performance and thus taking responsibility. But what surprised me most of all was how the promise that all these recordings would be listened to by us had set a form of mental dialogue in motion. What is in Psychoanalysis called transference unfolded almost in the pure form before our, no, not eyes, but ears.

Having become hypnotized after few of these takes, the following performance unleashed a mental cataclysm in me, a brainstorm of immediate questions. Not much was heard at the beginning, just a clearing of the throat, then a few heavy breaths. Obviously, the person was very nervous — which after a while, he articulated: "I don't know why I'm nervous; I'm all alone in this room.” And then, after a long pause, "Funny, I feel like the walls are closing in on me." To focus on the situation, he now began breaking down the entire process into its details: how each of his words, once articulated, dissolved into a sound wave, how it hit the membrane of the microphone, was translated into electromagnetic information and was written by a recording head onto the magnetic tape. And the listening process would proceed in the same way: At some point, someone would insert the tape, the electromagnetic voltages would be read by the read head and converted back to sound, and now another person would listen to the sound of his voice. The way he analyzed this process was equally thoughtful — or as if someone were spinning himself a mental vest. After a long pause, a pop sound followed — quite obviously, he was now holding the microphone; at least his voice was very close when he said: "Funny, that looks like it has hair." My colleague snorted — but then followed that sentence, which seemed to me as if a veil had suddenly been drawn away from my inner eye. "It looks like when I discovered the hair in the priest's ear through the grille." That was it! Not only did this process represent a form of transference in the technical and psychoanalytical sense, but furthermore, the machine took on the role of a symbolic father here. And with this sentence, the room we had set up for our students had turned into a confessional, just as each recording represented a confession from which the actor hoped for absolution.

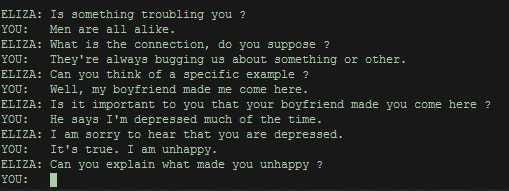

Even before these conclusions were burned into my brain, a story came to mind Joseph Weizenbaum had told me about his Eliza program, which had earned the aura of artificial intelligence in the 1960s — even though this chatbot was as far away from artificial intelligence as the earth is from the moon. If it excelled at anything, it reflected in question form what the user had just typed in as a statement. "I'm not well today!" "Oh, you're not well? What's bothering you?" Then, while working on this paraphrase machine, Weizenbaum noticed that his secretary, deeply engrossed in her work, was typing something into her computer terminal whenever he walked through the outer office. What was strange about this hyper-engagement was that Weizenbaum couldn't remember having given her so many work orders in the first place — so he approached her a few days later to catch a glimpse of the screen in front of her. And what did he see? His secretary was sitting in front of his Eliza program and telling it how she was feeling: "Oh, you're not feeling well? Who knows, maybe I can help you." Indeed, Eliza was there — and it didn't matter that the secretary knew that Eliza was nothing but a Machine for paraphrasing, having long since converted it into a mechanical analyst.

All this flashed through my mind while the sound of this sentence reverberated – and many thought-puzzle pieces came together in my mind's eye to form a picture. And this picture explained everything. Not only did it explain that and why the acting students were mentally exposing themselves in front of the microphone, but it also made clear to me this whole setting we'd come together for had been heading towards this sentence and insight. Because there was nothing, absolutely nothing, wrong with that sentence. Nothing of what Goethe had meant when he aptly wrote: "Thus one feels intention, and one is disgruntled." Even the presence of an addressee who'd eventually listen to this tape had vanished into thin air — more precisely, into this voice that wondered about the hairiness of the microphone's guard and had found its way back, without transition, to that childhood memory: what it was like to be able to see the hair in the priest's ear through the grates of the confessional. Ego me absolvo. If the actors had discovered their out-of-tune non-ego in the production, this voice of self-forgetfulness was something reaching far beyond that moment. Even weeks later, when I recalled the thought process of a medieval theologian, I knew this sentence was key since it made it unmistakably clear why the Middle Ages had brought the Machine and the proof of God together. And it was on the tip of my tongue as I tried to make my editor understand my claim that the Machine was the unconscious — while he looked at me, skeptical and amused, like an entomologist looking at a rare species. And it may be that one writes books only for this reason: because one tries to clothe a conceptlessness in the right words.

Translation: Hopkins Stanley and Martin Burckhardt