If the Machine seemed as a kind of longing for me, it was because it marked the breakage of my genealogical chaining to the world of my fathers and forefathers: a whole seven generations of Pastors, interrupted only by a professor of English who'd written a textbook entitled The Little Englishman1. However, the discovery that I’d been mistaken was all the more irritating as I'd been looking for the far side – and instead encountered the confinement I'd been trying to escape. It was like a slowly swelling, disturbing noise, placeless tinnitus that hadn't yet been identified as such. It’d begun while sitting in the State Library, looking at early Renaissance paintings for hours. Curiously, this was already a return to the world of my childhood. Whenever I’d brought home a good grade, my father rewarded me with a postcard of a Renaissance portrait – with which he wanted to make it clear to me, en passant, that what is truly worth striving for does not consist in filthy mammon, but is to be found on the other side of the number: in the image, in the incommensurable.

That is what went through my mind as my eyes wandered over the open art volumes lying on the table in front of me. My intention may have been writing a chapter on the logic of the eye (or, more precisely, on the laws of the central-perspective image-processing machine) with the same cutting coolness which I'd previously used to immerse myself in the history of photography – but, at the same time, this rakish gesture didn't fit in with what I saw there: nothing but depictions of the Virgin Mary. I'd compared the thinking of the Renaissance philosophers to a philosophical clearing squad and had spoken of a symbolic patricide – but the pictorial material, as such, resisted my interpretation. For there wasn't merely theological baggage at work here, but clearly that the image motif of the annuntiatio (thus: the Ghost of the Father) had an inherent maieutic function – indeed, that the depiction of Mary, who an angel prophesied was to give birth to the Son of God, was itself the driving force of the new representation.

My father died before I finished my studies. Consequently, there was no longer an opportunity to ask why he'd chosen me, of all people, to debate theological questions with him. Perhaps he'd harbored an audacious hope that his second-born son would end up in theology; it’s more likely he'd assigned me the role of an advocatus diaboli as his intellectual sparring partner to whom he could expound his train of thinking – figures of thought that had already seemed highly outré, if not wholly cryptic, to his pastoral colleagues. In any case, at barely fourteen years old, I was presented with the Life of Jesus by Rudolf Bultmann2, who, as my father’s teacher at Marburg, introduced him to historical research. And because this was only the prelude to a regular series of discussions, it was followed by Hans Eberhard Mayer's History of the Crusades, a most horrifical criminal history that irreparably shocked me. Nevertheless, these shocking readings didn’t miss their mark. Because the more familiar I became with Luther's doctrine of grace and notion about predestination, the more apparent it came to me that I would flee to the ends of the earth to escape this nebulous language, what Adorno had so aptly called the Jargon of Authenticity. And now it seemed to me – as I studied the portrayals of Mary before me – I'd indeed succeed. I didn't feel any resentment about my origins, desire for demarcation, or burdens needing to be shaken off. To the extent that I'd followed my own ideas, I’d simply stepped out of the Parsonage's world – without zeal, without anger. All the more strange, then, was this discovery now, in the guise of the annuntiatio, that the conundrum of what the dogma of the Immaculate Conception that lay before me might have to do with the modern image-processing machine.

Although my Metamorphosen3 had already appeared, this unfinished question still wouldn’t let me go. And because I wanted to get to the bottom of the Immaculate Conception dogma, I shifted my research from the State Library to the Catholic Academy’s library, which was still housed in a Westend villa. If I'd already approached my endeavor with doubts, what I found was a simplicity that was almost more depressing than what my father had put me through. Curiously, a pomposity pervaded the Mariological texts that were hard to bear. I could see in my mind's eye how the authors went down on one knee, being overcome by a thrilling emotionality accompanied by only jumbled word chunks like mystery, miracle, and grace. At best, this devotional handition was controverted by the reference to an illusive woman, invoking a feminist reading and reminding the reader that Chartres Cathedral, for example, had been built where the Celts had worshipped a mother deity – this mythological grounding back to the earth suited me even less than the Mariological incense while I was trying to fathom the Virgin Machine. In desperation, I'd even written a letter to a Catholic bishop who’d seemed like a reasonably acceptable partner for an exchange of ideas – but only the feeling of a dismissive head-shaking resonated in the benign rejection letter I received from him a few days later. At some point, I came across a book by a Protestant theologian4 who'd traced this dogma's history in a positivist manner, like an entomologist. And the deeper I immersed myself in this history, the more I understood how I'd landed in a mental labyrinth. Strangely enough, it had almost nothing to do with biblical tradition, giving instead the impression of a delusional system wholly divorced from the rest of the world, where a monster seemed lurking behind every bend, every fork in the road. And as I wandered through all these corridors, I became aware that nothing was contemplative about the questions being discussed there – au contraire, they were of an almost insane radicality. No, that term is fundamentally wrong because radix means root, whereas the desire articulated here was precisely the opposite: escapism, ecstasy, an intellectual suicide mission whose goal was to catapult the Virgin's body out into space (as a woman without an abdomen if you will). If in Hamlet, the conduct of the Danish prince is characterized as a mixture of calculating madness (‘If this be madness, yet hath it method’), this was also true of the theologians' various dodges used to contain the absurd contradictions within their dogmatic edifice. All their adventurous inventions, seen up close, turned out to be almost indispensable moves, without which historical progress wouldn’t have occurred.5 When I read that the mystic Origen – musing if Mary had received the Word of God, the Logos6, and was propagating the idea of an ear-conception, followed, as a matter of course, by the concept of an ear-birth – this put me into an almost all-encompassing merriment as I understood, that structurally speaking, the model of a seminary was given: Just as it goes in one ear, it comes out the other. If this was the beginning of a genuinely divine comedy, this absurd idea solved a problem that had remained a historical mystery to me in the form of Gothic Europe. It was only where the dogma of the Immaculate Conception had become native that universities had been founded – whereas the Byzantine Eastern Church, in which the Hellenic heritage was far more pronounced, had not given birth to a single alma mater.7 This simple yet startling insight was that Cathedral architecture and construction, the university, book printing, and Renaissance painting were all inconceivable without this figure of thought – indeed that Europe had needed a Mariological Ascension Command Mission to shoot itself out of the world into orbit. And with this insight, the scales fell from my eyes: if the figure of Mary demonstrated anything, it was the apotheosis of the mechané. In the Mother of God, something was redeemed of which antiquity had only been able to dream: the defrauding of nature was finally put on stage. It is only on this basis that we could have turned the world upside down, that a sentence like that of Gregory of Nazianzus could be made understandable in the first place:

Virginity is what marriage merely means.

Since the Divine was primordial, while the secular presented only a faint reflection, Bernard of Clairvaux had been able to preach that the tree was a fallen column – indeed, the theologians had been able to turn the ladder of heaven upside down: As in Heaven, so on Earth. That was the battery that had fed my father's thinking – and because it had taken hold of the entire culture, there wasn’t an institution that hadn't taken its starting point in Heaven.

If with this thought the weight, yes, the mysteriousness of the story dissolved into a serene weightlessness, it also was simultaneously confronting me with the problem of how to pay homage, of all things, to the Immaculate Conception’s dogma in a postmodern world in which the critique of Christianity was considered part of good manners. Even more annoying – all the things connected with this dogma felt like an obscenity – and so it was almost an inevitability that I would let my essay, which appeared in the magazine Lettre8, start with a thoroughly controversial film scene:

In an American film – which could have been by Robert Altman, I don’t remember anymore much about the plot; but there was a scene that I vividly remember. A blonde career woman, looking like you’d imagine a blonde career woman to look, dressed in stilettos and a very short pinstripe jacket dress, who casually learns during a conversation negotiating a deal that a rival female has appeared in her private life. Then, just as incensed as she is triumphant (you're in an open-plan office, and she is sans panties) – she swings on the photocopier, hits the PRINT button and photocopies her sex, then takes the copy, stuffs it in an envelope, stamps it and sends it to her rival. I remember laughing – and yet, I don't know why. What is this strange message? What is it that is being transmitted here?

As a result of this essay, all kinds of invitations fluttered into the house – as if I had deconstructed the riddle of the woman without an abdomen to an astonished crowd of spectators.9 Nevertheless, when you spelled out its consequences, this thought had that same offensiveness Freud had felt when he admitted his lectures had caused such a fervent reaction of silence – as if he’d touched the world into silence. So it was that one day in a Salon, I found myself vis-a-vís with a professor who I was trying to explain the connections between the Machine, the Immaculate Conception, and the University Seminary – and found myself looking into the face of complete bewilderment as if I’d just described an encounter of the Third Kind or the landing of an Extraterrestrial Mothership.

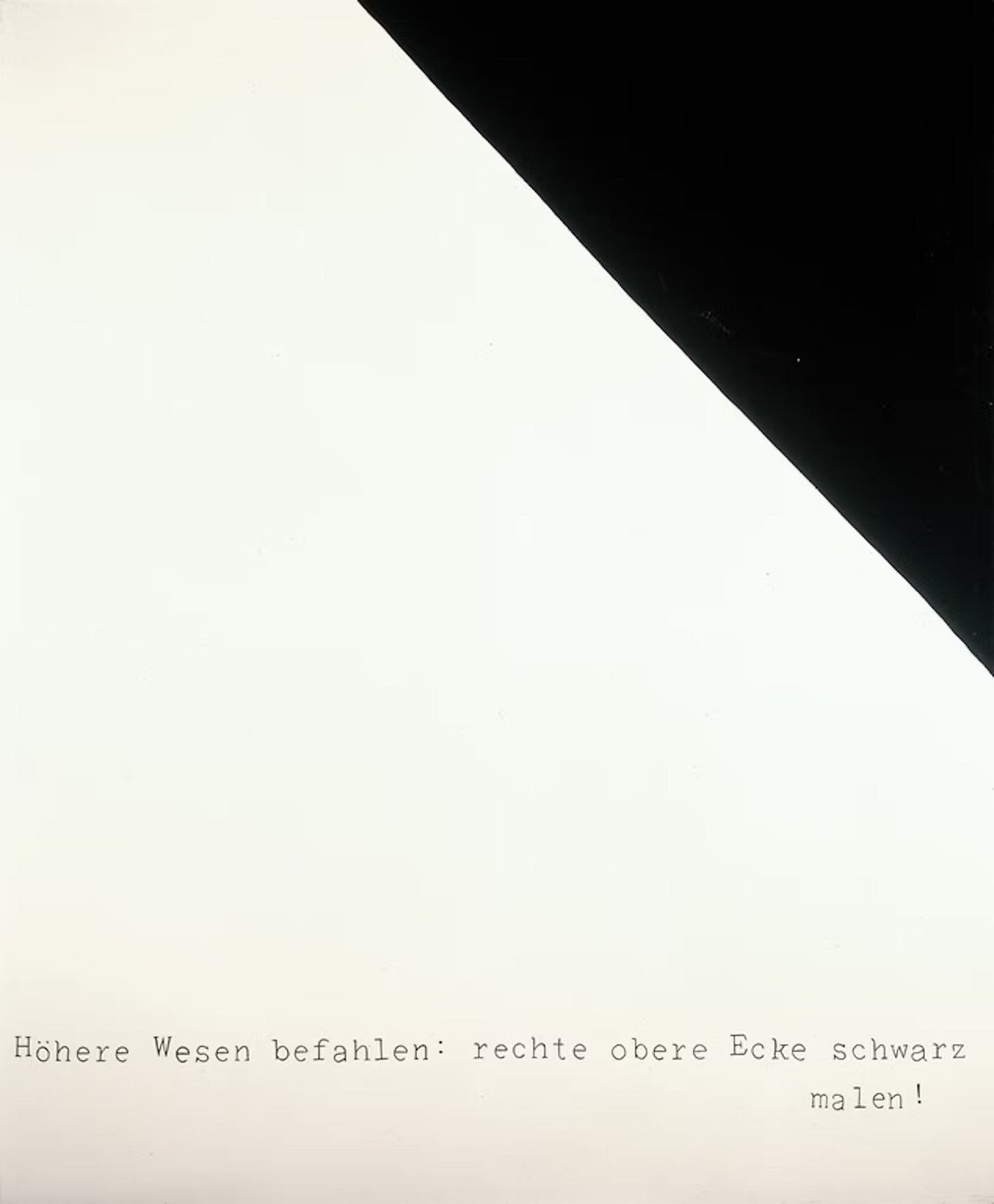

No, I don't know what would have gone through my father's mind if he’d attempted to follow my train of thought. I know only that I've trained myself regarding theological speculations with a friendly, you could say: entomological interest, an affectionate sympathy. How else can such a divine comedy be read? And so, without batting an eye, I would argue that the Immaculate Conception's Ascension Command Mission is one of the greatest and most consequential cultural achievements – the complete apotheosis of artificial intelligence. In this sense, it is no accident that philosophers and artists need conceptio; indeed, in every great work, one will find the evocation of a higher being. For this reason, even such a steadfast logician as Gottfried Frege must insist that a thought is something other than a hammer – namely, a form of timeless, higher inspiration. Or as the painter Sigmar Polke has translated this form of ear fertilization into a picture (where the comment reads: “Higher beings ordered: paint the upper right corner black! “)

Nevertheless: It would be nicer if we could be aware of being part of a great divine comedy – after all, this would be the moment when we escape the narrowness and can step out into the wide, where we no longer have to deal with godheads and metaphysical ghosts, but – with people.

Translation: Hopkins Stanley and Martin Burckhardt

Zum Nachlesen

Der kleine Engländer; oder Sammlung der im gemeinen Leben am häufigsten vorkommenden Wörter und Redensarten zum Auswendiglernen [The little Englishman; or collection of the most common words and sayings in everyday life for memorizing] was an aid book for learning the English language, and excellent for the exercise of memory, probably published around 1826. The author, G.F. Burckhardt (George Ferdinand Burckhardt), a relative in Martin’s paternal lineage, was the son of a theologian who traveled to London in 1780, then to the US, where he published this book before returning to Berlin. Of note, this work is apparently in the US public domain, and there are multiple reprints by small publishing houses that cite it as historically significant. [Translator’s note]

Rudolf Bultmann, a Lutheran theologian at the University of Marburg, was known for his existential interpretation of the New Testament using a hermeneutical methodology, arguing that what mattered was Jesus existed, preached, and was crucified rather than the mythology that gathered around him. Notably, he became friends with Heidegger while the latter was teaching at Marburg. He insisted that while his conversations with Heidegger influenced his thinking, he wasn’t entirely swayed by it. He also taught Hannah Arendt, was critical of Nazism, and joined the Confessor’s Church which arose in protest against unifying Protestantism into a unified pro-Nazi Reich Church. [Translator’s note]

Burckhardt, M. – Metamorphosen von Raum und Zeit: Eine Geschichte der Wahrnehmung, Frankfurt/M, 1994. [Translator’s Note]

Delius, W. – Die Geschichte der Marienverehrung, Munich / Basel 1963.

A beautiful example is how the problem of original sin had been eliminated. According to Augustine's teaching, no human being was free from original sin, so the theologians' efforts to impute a pure, sinless life to Mary would have been in vain. The solution was, again following Augustine's teaching, to liberate the carnal union of her parents from the evil libido – with which the divine miracle (and the core of the dogma) consisted in the fact that her parents Joachim and Anna could commit the procreation of Mary in perfect lustlessness.

The astonishment Martin saw here was the dissemination of mythological stands of artificial reproduction in the relations between the metallurgical cults, the birth of Zeus, the logos spermatikos, the Alien God, and the Immaculate Conception, which he weaves into the leitmotif of the lost-form and its unified dissemination from the Gothic Cathedral seminaries across the Occident. See Burckhardt, M. – Metamorphosen von Raum und Zeit: Eine Geschichte der Wahrnehmung, Frankfurt/M, 1994; Vom Geist der Maschine: Eine Geschichte kultureller Umbrüche, Frankfurt/M, 1999; and Philosophie der Maschine, Berlin, 2018. [Translator’s note]

The Athenaeum in Constantinople, founded in 425, is still faithfully maintained as the institution of the ancient tradition of the Platonic Academy. The Academy of Mangana, founded in 1045 as a School of Philosophy and Law in the Monastery of St. George of Mangana, next to the Imperial Palace, can, in turn, be seen as an institution with which the Byzantine elite was able to train and educate its heirs – which is also true of the first university founded on European soil: the University of Bologna.

Burckhardt, M. – Die Künstliche Mutter: Die Geburt der Maschine aus der Unbefleckten Empfängnis, Lettre International, 27, Winter 1994. Martin will later intricately weave this obscene image into his leitmotif in the third chapter of Vom Geist der Maschine (ibid.), titled Muttergotes Weltmaschine. [Translator’s note]

The fight against discrimination knows no mercy: After the carnival sideshow of the woman without an abdomen had been gracing the Wies'n of the Oktoberfest since the 1950s, the organizer was banned from performing at the historical folk festival in Stuttgart in 2022 because no freak show would be tolerated in the city.