Introduction

For our English-speaking readers, it’s essential to provide the historical context behind this humorously serious questioning of Robert Habeck’s remark on solving Germany’s energy crisis at this year’s Re:public1 event. Contextually, it began with Angela Merkel's one-and-done decision to shut down Germany's nuclear technology in the wake of the Fukushima disaster.2 Germany found itself on a special path [Sonderweg]3 of a separate energy policy, resulting in the country’s deep dependence on Russian gas. The advent of the Ukraine war significantly exacerbated this problem, forcing the Greens, who’ve been governing only since 2021, to accelerate their much-praised transitional Energy Turnaround [Energiewende] revolution even harder. However, the associated social costs of what’s been described by the Wall Street Journal as the World's Dumbest Energy Policy have suddenly become apparent as they’re finding their popular support dwindling. This leads to the strange paradox that the Green Party, which defines itself as a grassroots, citizen-oriented, and empowering political party, is suddenly behaving in an overly authoritarian manner – raising the question of the state's role.

Boom!

It's not that I dislike Robert Habeck – au contraire. Politically, however, what his ministry has brought into the world betrays an encroachment dwarfing any governmental interventions I’ve seen over my lifetime. So the question is: How did this happen? Now, at the last Re:publica, Robert Habeck talked to Johnny Häusler about climate policy – and, with a tiny remark, he gave us a deep insight: Because he recalled how the smartphone had caught on: And whoosh, there it was!

It’s here at 2 minutes, 54 seconds...

Now, the sloppiness of this formulation is not a lapse but reflects the political-philosophical conviction of his teacher Mariana Mazzucato. Following her lead, Habeck hopes that the state, much as it contributed to the smartphone revolution, can similarly bring about the Energy Turnaround’s great decarbonizing transformation of our industrial landscape. And because this is to be taken as exemplary, it’s worth devoting a few thoughts to the underlying theory. In her book The Entrepreneurial State (subtitled Another History of Innovation and Growth), Mariana Mazzucato asks what technologies the smartphone revolutions were predicated on – noting that GPS technology, touchscreen technology, and the Internet were all government-sponsored.

Undoubtedly, the idea that the digital revolution sprang from the minds of some garage tinkerers is a romantic transfiguration, if not outright folly – just as it’s doubtful the private sector was as daringly forward-looking as its staunchest (mostly neoliberal) advocates have claimed. On the contrary, if we take a look at the asset-backed securities of the 2000s, we’d be inclined to think that the financial industry preferred a foundation of fictitious capital (vernacularly: the printing of money) to the laborious economic cycle – which is why the self-proclaimed Masters of the Universe should be much more accurately understood as a herd of risk-averse lemmings who collectively rushed toward an Abyss. From this perspective, Mariana Mazzucato's criticism is entirely justified – the digital revolution would not have been conceivable without the support of the American military, DARPA, the Department of Defense, and the Manhattan Project. However, Mazzucato's conclusion that the state is the better entrepreneur shows an audacious ignorance of factual development. Au contraire – the latter doesn’t justify trust in state planning. While the retrospective view may interpret history as a meaningful chain of events, the situation becomes much more enigmatic if we analyze the contexts of concrete historical facts. At any rate, it wasn’t until the computer pioneer Vannevar Bush took over the scientific coordination of the Manhattan Project that any of the War Department Brass could have even considered handing control of the project’s development and funding over to hard-to-control eggheads – any more than the military would have favored the development of the DARA-financed Arpanet. And what was true of the military was also true of the influential politicians. As almost always, the classe politique found themselves on the wrong side of history. This is less surprising since the Lack of Imagination didn't even stop at the developmental pioneers, or the nerds of computer culture themselves. Although the copier manufacturer Xerox produced the first personal computer, the Xerox Alto, in the early 1970s, they didn't become the world's largest computer manufacturer because of the company executives’ Lack of Imagination when observing a product demonstration – they saw nothing but a group of casually dressed nerds typing away on keyboards in Birkenstock which they decided was nothing more than women's work; neither economically sound nor profitable.

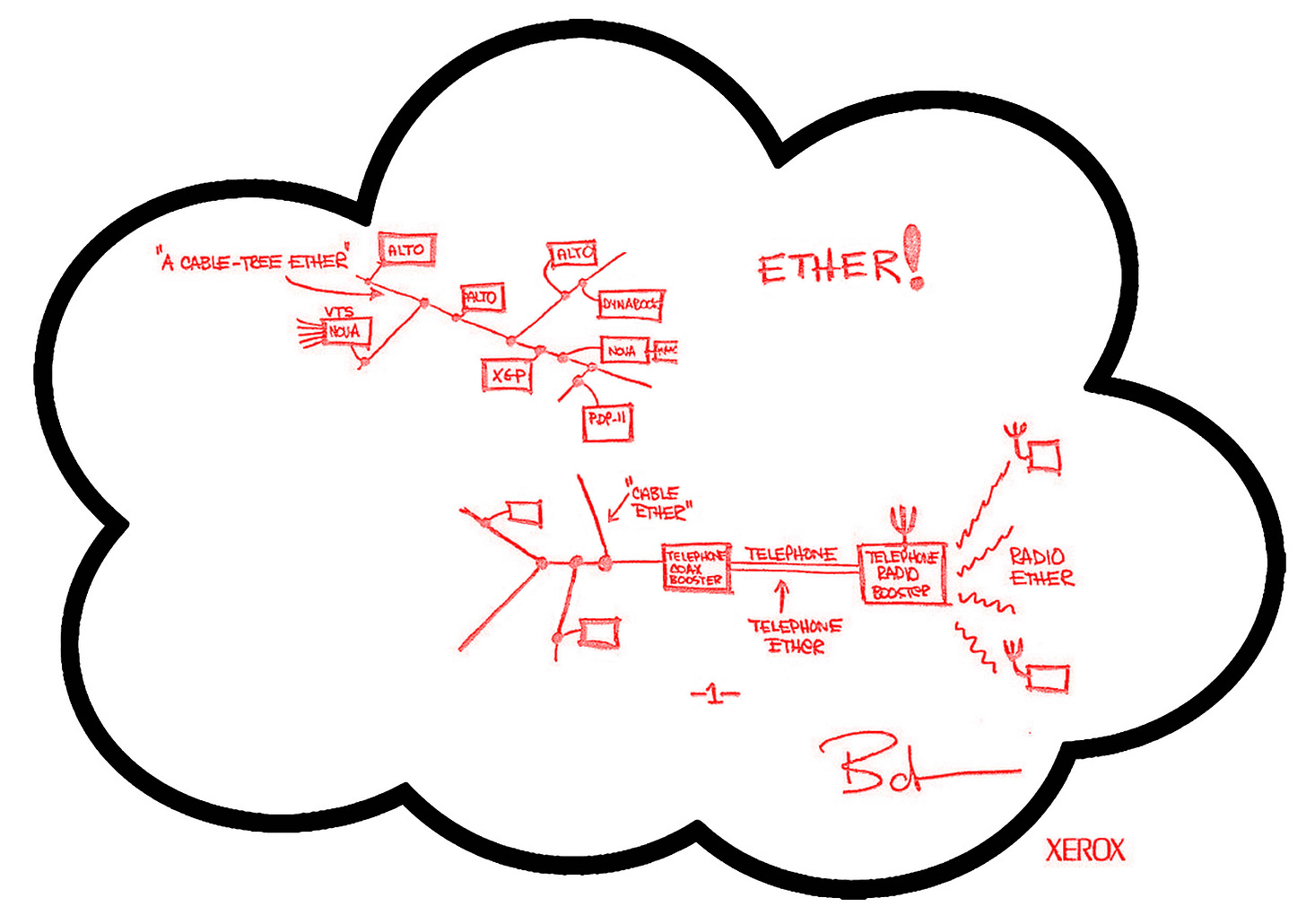

Even more radical is the story of Robert Metcalfe, who, in the early 1970s, was tasked with networking Xerox Park's computers. None of his colleagues were enthusiastic about this networking logic. And why? The simple answer: if my desktop has several months' worth of my work stored on it, networking means my neighbor can take possession of it with the click of a mouse. And because this involves a breach of ownership, the nerds themselves did everything they could to make Metcalfe's Ethernet project fail. Of course, Metcalfe prevailed – and the success of networking spawned all sorts of innovations, such as the @sign, which Xerox Park employees began using to write each other emails. And, even though everyone started using the network, its usefulness wasn't officially acclaimed until it went down – and within five minutes, the entire staff was in Metcalfe's office asking, Where's the network?

If we seriously engage with the history of digitization, we’re confronted with a series of paradigm shifts – wonderfully prefigured in the scene above. If a crisis of property, a crisis of work, or even a crisis of individuality shines through here – and if this development affects even the propagandists of this development – then the thought itself suggests we’re dealing with a profound change in worldview, a change moreover, largely taking place unconsciously. When Mariana Mazzucato writes: the success of these technologies is overwhelmingly due to the foresight of the US government in envisioning radical innovation in the electronics and communication fields going back to the 1960s and 1970s4, this statement borders on mis-directionally misleading – you could just as rightly argue that every achievement rewarded with money goes back to the state – meaning that the state, which brought fiat money into the world, must be seen as the actual originator. The audacity of Robert Habeck's heralding dream of a new disruptive phase in the development of a post-material society as a creative destroyer à la Schumpeter becomes visible in that the fundamental question of energy turnaround has already been missed right from the start – and on several levels. We're talking here about the novelty of a classic top-down supply being merged with a decentralized, bottom-up logic – where the traditional end consumer can now appear as a prosumer (as Jeremy Rifkin has called this type). If such a mixture announces a liquid society, its first answer would have been a computational layer where it could be determined who, at any time, feeds in or is consuming how much energy and where – and if this had been combined with a promise that the consumer would receive a ten percent reduction on their electric bill, there wouldn't have been any need for the currently-issued punishing threats. A second point, which would have argued in favor of building such a smart grid, is that renewable energies impose a fluctuation in availability on the system, which can only be managed by utilizing such an information layer. Now it's evident that such a network architecture (keyword: data protection) is politically explosive – a rethinking of what the relationship between individual interest and the common good in a network and its costs would have been considered. But no such efforts of persuasion have been made, nor have the material, spiritual, and political implications of such a network been thought through. The fact that politicians still aren't aware that the energy turnaround they proclaim means nothing more than the foundation of an energetic Internet can't be understood as anything other than being out of touch with reality. And it is precisely at this point that Mariana Mazzucato's argument becomes politically questionable: what appears here (and has become a form of government action in Germany) is a primitive statism that, even if it cloaks itself in a hipster flair, ultimately leads to a return of the Prussian authoritarian state – with the difference that the pathos of saving the world has replaced Prussian enthusiasm for machines. How did Emmanuel Geibel end his poem Deutschlands Beruf?5

And the world may yet be healed by German nature/One more time.

Please don't!

Re:publica is an annual conference on all things relating to our information society.

Germany’s anti-nuclear movement is an outgrowth of the ‘68 student revolution, beginning with the successful protest against Wyhl's nuclear plant construction in the early 1970s. While the movement’s concerns regarding the Chornobyl disaster were valid, it was also informed by a sophomoric understanding of technology and administrative governance, as exemplified by their early fears of computers, which has led to the current Greens turning pale as they navigate their mandated policy of Energiewende with its disastrous social disruptions and ill-thought-out solutions often demonstrating a lacking understanding of both history and technology.

Sonderweg translates as a uniquely separate, special path – referring to a German historiographic theory considering Germany as having its course different than any other European nation. It can be seen as analogous to the American Imperialistic notion of Manifest Destiny.

Mazzucato, M. – The Capital of the State, New York 2015d, p. 182.

Deutschlands Beruf? [Germany’s Profession] is the title of Emmanuel Geibel’s 1861 poem about calling the individual German states to gather under the German Emperor Wilhelm I. Historically, the line from the poem, Und es mag am deutschen Wesen / Einmal noch die Welt genesen [And the world may yet be healed by German nature/One more time.] became an important political slogan used by the German political leadership to rally the German people during the German Austro-Prussian War of 1866, the Franco-Prussian War war of 1870-1871 under the Prussian prince Otto von Bismarck, and WWI. What’s being captured is this sense of purity-in-heart implicit in the German character, involving calling beyond vocation and profession to unify and lead the world through Prussian superiority as a cross between a vocation and a profession (see Footnote 3 in the Introduction above.)