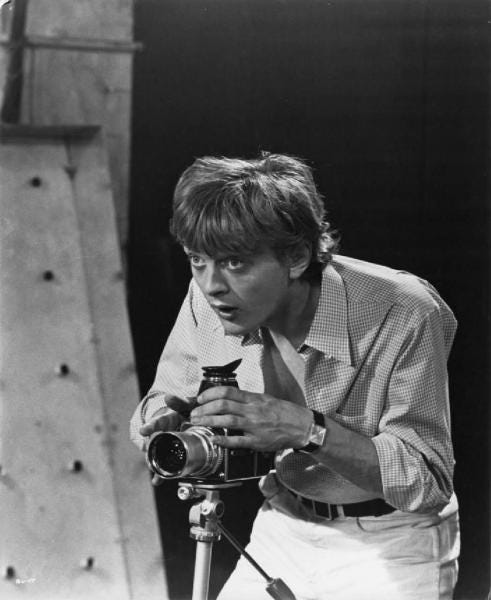

In his Little History of Photography,1 Walter Benjamin points out there's a kind of optical unconscious that the photographer, like the hero of Michelangelo Antonioni's Blow Up, discovers only during the photograph's development. Here, it is realized that an event was witnessed when the image was captured on film, of which the photographer was completely unaware.

That the armed eye’s gaze casts an otherwise denied glance into the world isn't new, as Goethe and Freud were already preoccupied with it. It wasn't surprising then that a philosopher like Hans Blumenberg saw the beginnings of Modernity in the telescope. While the age of drone warfare may have finally proven that the gaze can kill, this fixation on the visual is misleading. In the Digitalised World, everything electrified becomes a Sign—whether it is my voice, a whale’s geo-position data, or a Mars rover's sense of balance. At this point, it was precisely that the program Simon Michelet has developed over the last few months gave us a great surprise. Confronted with the possibilities of AI image production, we saw every text and every conversation is actually a stream of consciousness that - in addition to carefully selected images - is true to the Nietzschean idea that every word is a prejudice as it conjures up every conceivable metaphor from the pool of its meanings. In other words, I'm not alone as a unique and unmistakable original genius when »I« speak – but I am always also the one calling the phantasms of the past into being in the form of metaphors, idioms, figures of thought that have taken on a kind of inherent mobility. In this sense, words are also equivalents of the strange event that myth tells of. It’s said that Daedalus created such life-like figures that they simply walked away the moment he turned his back on them. Thus, the question that Simon Michelet devoted himself to with programming, which was as grateful as it was patient, arose: What does a text or a conversation look like when you’ve distilled it down to its central metaphors and linguistic images? More precisely, what kind of images emerge? The results we ultimately came up against were surprising in many ways – and most importantly, they showed that all writing contains a form of the unconscious in which »IT« speaks (or ID?). If you transform this »IT« back into imagery, you descend into the catacombs of speaking and writing, into that sphere where a form of wild thinking prevails - or where, as Roland Barthes so beautifully put it, desire writes the text. While reason gives the impression that we carefully use words, endowed with the power of definition, and know precisely what they mean, these images plunge us into a surreal daydream world.

Perhaps this is where Simon's program led us to its most surprising insight: that such a form of image production transcends much of what even the most daring imagination could have imagined. This has to do, not least, with the fact that language in the age of artificial intelligence is understood as a resonating social body - and that, in the use of words, we're dealing with a social sculpture. Should we criticize this? Quite the opposite. If you look at what Simon's thought and metaphor processing program brings to light, you can't help but see something quite magnificent and delightful in it.

Here are a few examples:

This text illustrated

Related Topics

Delirium of Images

It's probably unusual for a programmer to speak up from behind the SCENES. After all, we are relatively self-sufficient, and because we're literally lost in coding, we find little reason to appear in public, especially in such an intellectual environment like this. It's only because Martin Burckhardt convinced me to put aside my reluctance, at least tem…

See Walters, B. – Little History of Photography in The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media, Editors M.W. Jennings, B. Doherty, and T.Y. Levin, 2nd ed., 2000, Cambridge, Mass. He also discusses the Optical Unconscious in his essay titled The Work of Art in the Age of Its Mechanical Reproduction in the same volume.