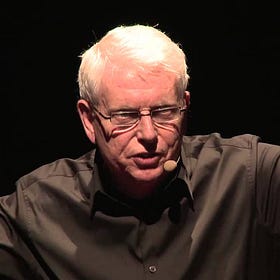

The fact that the monetary order is a mystery even to the majority of economists is perhaps one of the greatest oddities of our time. This is the subject of this interview with Heiner Flassbeck, former State Secretary and long-time Chief Economist at the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development in Geneva. The conversation took place on October 18, 2024,

Martin Burckhardt: Dear Mr. Flassbeck, in today’s conversation with you, I’m looking forward to discussing the more significant economic contexts given the current calamities – which often point to blind spots inherent in contemporary economics, whether neoliberal or neoclassical. But first, a few words about you: after being appointed by Oskar Lafontaine to the German Federal Ministry of Finance [Bundesminsterium der Finanzen] as his advisor, then, for a short time, you served as a state secretary. From there, you became a senior economist at the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) before becoming its Chief of Macroeconomics and Development—and then the Director of its Division on Globalization and Development Strategies. Recently, after writing a fascinating book on the failure of globalization1, you summarized the essence of your knowledge in a voluminous work entitled Grundlagen einer relevanten Ökonomik [Fundamentals of Relevant Economics]2. I think one of its characteristics, dedicated to the big picture, is how you're not only at odds with your own discipline but also with our government's economic expertise—leading me straight to my first question: When did you realize you were entering into a profound disagreement with your own profession?

Heiner Flassbeck: I realized this as early as the 1970s when I joined the German Council of Economic Experts' staff and saw how little essence there was to the whole thing—how much water was in the wine. And, even though I observed a few simple biases, I thought, ›This can't actually be the case. It can't be that an entire field is so weak.‹ But then it went on and on, only confirming my suspicions. Even though the biases seemed minor, I realized it was a peculiar form of science. Today, I wouldn’t even call Economics a science anymore; it’s more of a game. I've always said that it’s a Glass Bead Game, referencing Hermann Hesse's wonderful book3...a game that, while requiring excellent intellectual abilities from its players, doesn’t make a lot of sense in the long run because it simply serves to keep intellectuals busy satisfying themselves while having nothing to do with reality. The only stupid thing is that the people playing this game on a large scale worldwide are repeatedly asked by politicians to answer things they can’t just because they call themselves economists—that’s the dissonance I’ve always seen.

And because I’ve closely aligned myself with empiricism from the beginning in the 1970s until today, I’ve continually asked myself: ›What is happening? Can you explain what is happening? Why can't you explain it?‹ And I haven’t limited myself to saying: ›Where is the market in this when something happens...where is a market, and how can I incorporate the market so that it explains what is happening?‹ But that’s the prevailing economic approach because they always have the Market in mind – so when something happens, they say: ›Yes, there must be a market behind it that we don’t yet understand or have discovered. So, let’s try to discover and describe it.‹ And then, if you describe this invented market, which doesn't even exist, you need 200 assumptions that, as such, have nothing to do with the world. All is good because everyone is happy to have discovered something, even if it has nothing to do with reality. Then, Milton Friedman, one of the most famous economic ideologues or monetary scientists of the last decades, once said, ›Yes, it doesn't matter whether 10 or 20 assumptions are realistic assumptions or unrealistic because if we show a market is functioning somewhere in the nucleus, then it is already good and undoubtedly correct. The entire statement is accurate because it is all based on the Market.‹—but that’s simply wrong!

MB: What has psychologically encouraged you to continue insisting on a reality principle, that is, on a view of reality where the economists, who are required to vouch for the ultimate wisdom of our reality, aren’t in charge? How were you convinced that this wisdom might somehow be unwritten after all?

HF: There are a few steps in the history of Economics, which I’ve set out in my book, where there are already a few cracks in this system of the Glass Bead Game. Everyone knows John Maynard Keynes and his economic doctrine, Keynesianism. Keynes was, and still is, truly important, but it’s easy to see how the cracks in Economics developed after the Great Depression’s incredible shock to the World Economy. After something terrible happens, people are open to new ideas, such as Keynes’ terrible theories. But there’d already been these rifts where we’ve seen that, ›Yes, we can do something with a different description of reality‹ – while, in my eyes, Keynes remained too much attached to equilibrium thinking. He said the most challenging thing was breaking away from ›what has been drummed into you from an early age,‹ so to speak – which, since his father was also an economist and philosopher, he’d absorbed with his mother's milk, poor guy.

And then there's a second big name that also plays a significant role in my book: Josef Alois Schumpeter. An Austrian economist, Schumpeter wrote the most comprehensive work on the History of economic analysis,4 which he hadn’t finished editing before his death. It’s over 1,000 pages long, covering every nook and cranny of Economics, perhaps the most extensive knowledge of any human being on the subject. Although he neglected his own achievements, perhaps out of modesty, he had already accomplished a magnificent feat when he wrote The Theory of Economic Development5 at the beginning of the last century. This is the first and, strangely enough, the last attempt in over 200 years of Economics to dynamize the whole thing—to move away from equilibrium thinking towards a dynamic view of the economy. Having read that early on, I have to say it impressed me and today, it’s one of the pillars or driving forces behind my economic thinking, which is Schumpeterian on a micro basis.

MB: You have a clear view of the fact that and to what extent neoliberal ideology has obscured our political sphere, which I, who’ve been dealing with the history of the Central Bank for a long time, absolutely appreciate. Milton Friedman wonderfully describes this fading out by illustrating the emergence of markets. He has helicopters fly over an island, dropping bags of money. And because the islanders immediately understand that here it isn’t manna raining down from heaven, but money – markets, prices, the dynamics of supply and demand, and the like, all arise. However, this fairy tale doesn’t mention something fundamentally important: that money doesn’t fall from the sky but is issued by central banks. Without this institution, the miracle described by Bernard de Mandeville at the beginning of the 18th century would have been impossible: private vices turning into public benefits. The 17th century, before the founding of the Bank of England, can be described as a period of monetary anomie, chaos, and even an ongoing monetary civil war—as your economic hero, Josef Schumpeter, did. So how were the neoliberal economists able to believe that money falls from the sky Economy, and could they ignore the importance of political institutions?

HF: This is again related to the Glass Bead Game of economics; for money to be, there must be some kind of simulated market for money. Milton Friedman’s whole idea was modest in the grand scheme of progress. He took up an equation that, at first glance, doesn't say anything – but has been around since the 16th century, I think. It’s the so-called quantity equation. And they used it to construct, again, under any assumptions – it doesn't matter what assumptions you make – a world where there can be a Central Bank that’s completely politically independent and technocratically able to control the money supply. The money supply somehow falls from the sky, but the Central Bank controls it. This Central Bank’s technocratic control of the money supply, which is essential to distinguish, was the correctly defined idea of a controlled money supply existing in the economy. That’s how the demand for money and interest rates develops from where the interest rate is again more or less a market result.

Of course, this has absolutely nothing to do with the economy. There is no money supply—there’s also no money supply the Central Bank could even control, though they still claim that sometimes. In the 1970s and 1980s, the Bundesbank officially adopted this, which became the German monetary policy doctrine… even though we know the money supply was never controlled, the Bundesbank claimed it was. They said the Central Bank was behind it all—behind our interest rate management – but I have to say, what the Central Bank does now is simply set the interest rate: that's it. And then it keeps it where it wants it. Yesterday, we saw that the European Central Bank lowered interest rates; it could have reduced them six months or three or four years ago. It would have been just as good. It's completely arbitrary.

But economists are reading something into this by saying, ›Yes, it’s the result of a wiser concept, in which the interest rate is ultimately a market result.‹ That’s complete nonsense. It’s not a market result—it’s an arbitrary act of the Central Bank. It doesn’t matter if you have more intelligent or less thoughtful people running the Central Bank; something will come out of it—that’s all. But it was a subject of considerable hype, particularly in a cultivated Germany, and we can't ignore it. The USA has solved this much more intelligently, so there’s no need to argue about the independence of the Central Bank or anything like that. In the US, back in the early 1980s, they said that after monetarism was overcome—mind you, Germany has a knowledge deficit of around 30 years, which isn’t much—the Central Bank also had to ensure a high level of employment. And then: poof, that's it…the illusion’s shattered, the bubble’s gone, and the balloon’s burst: the Central Bank simply has to make economic policy. However, this monetary policy must be coordinated with the rest of the economic policy. You can't say ›We're making Central Bank policy having nothing to do with the rest.‹ And that's the end of independence for now.

But in Germany, it's taboo that you're not allowed to talk about this. When Mr. Trump said, ›I can also do monetary policy; I could do it better than the funny central bankers.‹—there was an immediate outcry in Germany. The German Business Press wrote that Trump's breaking a taboo was terrible. However, this taboo was already broken 30 years ago when it was said that the Central Bank should also be responsible for employment.

MB: Schumpeter describes, which I find incredibly interesting, that the early 17th century was a real-time of anomie—Holland had 32 central banks, some of which were family-owned. What you’re experiencing is what Marx was already thinking about – that the pound, which was a pound of silver at some point – more or less disappears into thin air when it becomes a component of something. Then, going back a hundred years and looking at what suddenly happened after the founding of the Bank of England, you realize Bernard de Mandeville’s sentence about a private vice turning into a public benefit was virtually impossible before that in the 17th century, which Schumpeter describes as a period of monetary civil war—but the moment when the State appears as an actor pacifying the interest rate in England and can switch to assignats, you suddenly have something like a market. And I've always wondered, if you go into a national library and look at what’s been written about the history of the Central Bank, it's almost a nirvana because there are only a few books about it – it’s like a history that hasn't been written.

HF: Yes, the Mandeville story is that, in principle, you can also organize it privately, so that’s not crucial. You can also say that today, the FED – the American Central Bank isn’t a State institution—I think it’s a corporation or private ownership, but that's not important. What’s important is that this institution has a clear public mandate. They can then make their profits, and whatever else they do is of secondary importance. However, as most countries have done, the State can also organize it entirely. For us, it's a Ministry of Finance department, as was the Central Bank in England until about 15 years ago. That doesn't change the fact that this money has to be spent on economic development.

Schumpeter clearly stated and demonstrated in his theory of economic development that we need money created by the State and banks since banks also create money under this umbrella. When banks grant loans, they provide the money necessary for economic development, which was the sticking point. Before and after that, economists still claimed that money was neutral and the veil. When you throw a veil over the economy, it's called money – and when you pull away the veil, everything is the same as before—that’s grandiose nonsense. It's pure ideology. They wanted to prevent politicians or outsiders from influencing their beautiful markets. But of course, that's not true. Money is crucial for economic development. Central bank policy, as every child should know today, is key to many things, not just fighting inflation. I explained this very clearly in my book. It’s not, and it can’t be the main task of the Central Bank to fight inflation, whose main task must be to stimulate investment saturation. Fighting inflation can be done in other ways, namely, first and foremost, through an income policy and sensible wage development.

MB: You could say that the idea of the market, which consists of nothing but the homo economicus, is heading towards the phantasm of a Hegelian world spirit. And just as Hegel replied to his critics when they complained his theory didn’t fit in with the facts, ›All the worse for the facts.‹ The economists' profession prefers its model calculations – and when you are dealing with ideals, the practical world is more of a hindrance for them. This might be bearable if Economics was still a niche science, but there’s probably not a politician who isn’t, as John Maynard Keynes so aptly put it, the mental ›slave of some dead economist.‹ Looking back at the financial crises from the past four decades: Why didn't the economists see all this coming? And what did they lack to at least anticipate the coming disasters?

HF: That's very easy to explain. They believed in their market equilibrium and efficiency of the markets. Just a few years ago, an economist, Eugene Fama, was awarded the Nobel Prize for proving Capital markets are efficient—grandiose thinking they’re efficient because they all process all the information. No, that's nonsense—which also plays a significant role in my book. Capital markets aren’t efficient; they’re herd-driven objects of speculation abused by herds of speculators, creating all kinds of wrong things, like currency crises.

Most of our crises have been currency crises clearly caused by misguided Capital markets simply speculating in the wrong direction because they were profitable. It’s worthwhile if you’re running in the right direction with the herd…the direction the herd wants to take. It's all self-fulfilling because you’re creating the profit you expect through your actions. If the Central Bank or someone outside with an overview of the whole thing doesn’t intervene, there will be huge misallocations and wrong prices. We’ve seen an infinite number of false prices. And, of course, 99% of the ruling economics members can’t foresee this because it simply doesn’t exist in their worldview. So, it's straightforward to explain because everything on the outside is simply pushed away—and there can’t be people questioning the Capital Market’s efficiency. If you try writing articles now, as a good scientist, and send them to so-called independently refereed journals, you get the result: ›No, of course, you can't publish what you're writing because you're questioning the Standard Economics Model. You can't possibly be questioning the Standard Economics Model.‹ And again, here you see it’s purely an ideological event having nothing to do with science. A few months ago, more as a joke, I published an article with a young colleague containing unambiguous statements that specific theories, such as the theory of international trade, are wrong. We then received three or four replies from referees who didn't understand what it was all about—they didn't even understand what we were talking about. Then I wrote to an editor I knew and said, ›That can't be right. Why don't you find a referee who at least understands what we're talking about?‹ So he looked for another one, who again didn't understand it. It was evident they didn't understand what we were talking about. And he said, ›I'm sorry. I think you're right, and you have an important point. But I can't publish that because three referees said no, so it won't be published in Science.‹

MB: Looking back at 1987, during Savings and Loans’ first crash, everyone was using these computer models. Or you look at the dot-com bubble, when a small company called EM TV, which owned the marketing rights to Maya the Bee, had a more significant market capitalization than Lufthansa. Everyone was getting a Stupid Bonus, which was a term that haunted me at the time because you had the feeling that virtually everyone if they were stupid enough to run after it, had a real advantage. But then there were all these collapsing bubbles and the disasters that came with them.

HF: Well, they really have that. If you're in the herd, you have an advantage, at least for a while. The Americans also say: The trend is your friend. You may have seen a wonderful movie called The Big Short about real estate speculation, where one or two people in the financial markets ask themselves, ›Have we all gone crazy? Are we crazy? Has everyone gone crazy?‹ And then they conclude: ›No, they've all gone crazy. So we’ll speculate against everyone, and then we'll win something.‹ And indeed, they were all crazy. But in theory, it shouldn't happen that everyone is crazy—but everyone is crazy. We have currency speculation, and as I’ve said, we‘ve seen quite clearly that it leads to disaster. Countries with high inflation have seen their currencies appreciate—Brazil is the classic case—because of so-called carry trades, where money is borrowed from Japan at zero interest rates and moved to Brazil, earning 10% interest. That's completely crazy and should never happen because everyone would have the risk embedded in their brains if they were the right neoliberal market participants. But they haven't and couldn't care less as they shift billions to Brazil, bailing out at the last minute. They may have lost a little money, but before that, they'd made endless amounts of money for years. And none of my economic colleagues are looking at that. If you point it out to them, they say, ›No, I don't want to look now.‹ It's like with Galileo, where the critic says, ›No, we don't have to look. We know that we’re right. We don't need to look through your telescope. Because we know you're wrong.‹ That's the great thing because it’s exactly how it happened. You can write theater scenes about how deluded the economists were—and are.

MB: We talked with Thomas Mayer, the former Chief Economist of Deutsche Bank. And he told us a story about how he came to Deutsche Bank around 2002, which I think you remember well. Deutsche Bank was suddenly of the opinion they should only have securitized loans stamped as secure by an auditor. That's precisely where we are with these ratings. But that means the lender in question no longer looks at the economy and no longer listens to the business model. But if we follow Schumpeter's logic, we‘d have to say it’s actually the moment of creative destruction, the disruption—›that which I don’t yet know, that’s my added value – not what I know, not the securitized credit.‹ This is a collectively prescribed dumbing down. Is that a bit too malicious?

HF: No, I can say – although I may disagree with Thomas Mayer in many respects – he’s right on this issue. Of course, they put stamps on everything. It was good as soon as it was insured, and the assumption behind it was pretty simple. As the movie The Big Short shows, house prices will rise for 100 years in America. If you believed that, then everything was fine. A lot of people felt that for a very long time. And because so many of them did, they were right for a while – even for five or six years. It was the same with the dot-com bubble, where everyone believed that anyone with a dot-com company would become a big thing. And that’s where we end up with the 99% and 99.9% companies, namely those that have lost 99% of their value and those that have lost 99.1%. And yes, that’s precisely the opposite of what a market should do, but that’s herd behavior, which you have to look at again.

Philosophically, neoliberals are strongly influenced by Mr. Hayek, who basically said the opposite. He noted herd formation is dangerous and shouldn’t exist at all, and what characterizes the market is that every single person comes to this market with their world of information, so to speak, and then acts.

That’s why we have such an infinite number of positions that can’t be wrong because they all have distinct and individual reasons. But that's not true for the Capital Market, which everyone knows isn’t individually based because they all have the same information, all acting at the exact moment – you can prove that as it can be shown the peaks on many Capital Markets move simultaneously. For example, when the American labor market report comes out, they go up or down. They do that on the stock, commodity, and currency markets. In other words, the same kind of information harmonizes all these markets. This is clear evidence there’s no Hayekian information processing. Still, no neoliberal in this world would look at it and ask himself whether it is still in line with his Hayekian ideal. I even discuss it with people here, but they’re utterly blind to it and don't want to know about it. It’s enough for them if they’ve adopted Hayek's ideology.

MB: We’ve come to the point that’s amazed me all my life: politicians and economists alike have seen globalization as the decisive driving force of our economy but missed that removing the distance of the World is an epiphenomenon of digitalisation. After all, it’s no coincidence that Bretton Woods' end was preceded by the Unix epoch, which was the development of the telematic communication system that made the emergence of global financial markets possible. Because of this, the 80’s and 90’s limbo economy developed. In this sense, what you aptly describe as globalization's failure is essentially an intellectual failure: the failure to grasp that Capitalism's new operating system is digital. Given recent events, it’s certainly possible to initiate re-shoring—bringing forces previously outsourced to India or elsewhere back home. Do you see this as a strange conceptual confusion?

HF: Yes, that's the crux of the matter. I just have to say that economists love globalization more than anything else, which is easy to explain and understand because they have no theory of development. We’ve talked about Schumpeter, whose theory of development is that the system develops independently, driven by the entrepreneur. You don't need international trade for that as this can happen just as easily in a region as in a country or even the whole world, as trade has no particular function here. But, since economists know nothing about endogenous driving mechanisms, they need an exogenous driving mechanism that can only be Trade – and nothing else. So this world is stupid in how it’s somehow limited by the fact that we already have the Chinese and the Indians in it...nothing comes after that. It can’t go on after that if the only driving force is international trade. And it’s with this image that they’ve thrown themselves into globalization, and, in the end, they’re terribly disappointed with this globalization because it’s an entirely different process than they’d assumed it was—and doesn’t work the way they imagined it would. And then there’s the financial markets you’ve mentioned. Where we really had supplemental globalization, it was essentially a false or inappropriate one. My main criticism is that the entire system wasn’t considered—what kind of global regulation is needed for globalization to function? Nobody wanted to think about that.

Now, I’ve made attempts myself as when there was commodity speculation, and, as UNCTAD’s Chief Economist, I held a major international press conference in New York with American politicians and others, including a president from Central America. We tried to make the global public a little more aware of what is happening—that commodity speculation is killing people…and that it’s a terrible thing. And what happened? Nothing. People closed their eyes and covered their ears. People didn't want to admit it because they believed in the fiction that the market always works properly. Even Paul Krugman said, ›Yes, it will work out in the end.‹ But no, it just doesn't work because globalization has been overlaid with these extreme processes. Whether you digitalise them, and digitalisation is a prerequisite for this—that’s absolutely clear. After all, we have trades processed in milliseconds. Of course, this isn’t possible without digitalisation. However, you can see that crazy Capital Market processes existed in the 1920s, as did crazy currency speculation in the twenties and thirties. So, the system is always superimposed on a Capital Market, where the real world delivers much less than the Capital Market. As a result, we get incredible distortions in the system.

MB: Globalization applied to economists—a wonderful passe-partout since everything could be obtained cheaper elsewhere. So the big word in the 90s and 2000s was locational competition – then suddenly, there was outsourcing and downsizing. And if you think this logic through to its end, it means that everything is cheaper somewhere else.

HF: That’s the driving force. That's where progress comes from...

MB: If we’d set our sights on digitalisation, we would have said we’re with Schumpeter—with a creative destroyer. We would have had to say, ›Okay; we’re suddenly dealing with disruptions that weren’t anticipated like this.‹ Henry Ford once wonderfully said ›If I’d asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.‹ So, every story eventually catches on at some point, both before and in the digital world; it’s essentially a level break—the creative destroyer. And digitalisation was, if you like, the blind spot of people who didn't want to deal with economic processes. That's why this story by Thomas Mayer is interesting. Securitized credit also means: a collective of the blind leading the blind.

HF: As I said, the underlying assumption is that we don't always understand the processes taking place. Locational competition! The biggest mistake people claiming to understand economics can make is talking about competition between locations. They should have known that this is nonsensical and can never work. How are countries supposed to compete against each other? Should States compete against each other? Applying Schumpeter's model to States means that States can disappear—but strangely, States don't disappear. Germany can't outcompete France—we tried but failed, as France still exists. Of course, our location competition has done a lot of damage to France. How crazy is it that this has been used as an official model for decades…they also don’t understand how competition with developing countries works—China’s the classic case. But China isn’t a case where, in retrospect, you can say they are having trade surpluses again, as they're now saying – while the Germans don’t—no. Even though the Germans are three or four times larger per capita than the Chinese, that doesn't matter because if it's against the Chinese, it's all good.

But we’ve needed the Chinese for decades. And what did we use them for? We moved our factories there. Our companies moved their ultra-modern factories to China, where they staffed them with cheap Chinese labor, making production cheaper. Now, the Chinese are doing it themselves, which, for God's sake, mustn’t ever happen under any circumstances – even though it has! This is another example of economic failure—namely, the direct investment process of combining highly productive Capital with low-paid labor, which doesn’t exist in theory. As I mentioned earlier, that was precisely the topic of the article we tried to publish. The problem is economists can't begin to understand it because it doesn’t exist in Economics. It’s inconceivable to them that you could put an ultra-modern factory in China and then have low-paid labor there because – after all – workers have the same productivity everywhere—the vaunted marginal product. That’s the way it is with economists: Everyone wears a piece of paper on their shoulder; one says, ›I'm productive at 12 euros/hour,‹ another says ›...20 euros/hour,‹ while another says ›...2 million euros/hour,‹ and that's God-given – you can't do anything about it—which is completely crazy. In reality, people don't work like that; they work under the conditions they are given. They work productively or not productively, depending on the conditions. And, of course, the Capital they’re given is the most critical condition.

But there’s other conditions, like clever bosses who deploy people intelligently, and then there are workers twice as productive as a stupid boss who doesn't understand their potential. The big thing is that economists erase all of that, replacing it with some stupid, simple, ridiculous fiction – such as people having specific marginal productivity. If they exceed it or get paid more than the corresponding marginal productivity of the minimum wage, the situation is immediately dismissed, and they’re immediately fired because it’s no longer worthwhile for the employer to work with this person – because there’s no justification for it. The implication is, as I’ve always said, you have to imagine a primary school teacher who has always done the same thing for 500 years—always teaches children reading and arithmetic because they’re always born stupid. There's nothing you can do about it. We may be super-intelligent, but children are all born equally stupid, so there has to be someone who always teaches children something and doesn't become any more productive over the decades or centuries. In other words, in the theory of prevailing economics, this person has consistently received the same money for 500 years and is now so poor that he’s constantly starving. What does that show? Simply nonsense. He always does the same thing, so he is equally productive or unproductive and yet gets more money. And why does he always get more money? Because otherwise, nobody would do it anymore. These people have a right to remuneration because they’re part of the team; without them, the whole thing wouldn't work. And even if their individual productivity is extremely low or always the same and never changes, they still have to participate in progress as part of society—which again shows the whole idea of marginal productivity and neoclassicism simply belong in the scrap heap of history.

MB: I’d like to return to the question of Bretton Woods because it is interesting since we’re dealing with the dematerialization of money. It raises a very strange question – about not only the dematerialization of money but also the development of the global financial markets. If Capital has left the Capital Markets, who’s the one that, as you say—and I think it's wonderful that you use this term—can act as Capitalism’s system operator? Is this still a matter for Nation-States? Or haven’t we long since been dealing with a structurally atopic post-national order?

HF: Yes, we must have supranational organizations to do this. We have some, but really only one that’s relevant in working with the markets while also controlling them to some extent—albeit only a little. That’s the International Monetary Fund, established by Mr. Keynes in the early 1950s, based in Washington. It was the Central Bank part of Bretton Woods, although whether it was as a genuine supranational or a supporter of the national central banks isn’t decisive anymore. What’s decisive is the idea that we absolutely need something like this. And there’s another institution, the World Trade Organization in Geneva. They should work together and ensure that we get a system that makes rational trade possible, not according to this theory or utopia of absolutely free trade—which doesn’t exist, but according to a realistic trade theory promoting exchange between nations through dialog with each other. You can't just blame the Chinese for everything without an institution that plays the referee and can say, ›People, it's not that simple‹, or ›You can't deal with each other like that‹.

Then there’s the International Monetary Fund for the Capital side—only it failed fundamentally, as has the World Trade Organization in some respects, but I won't discuss that now. But the IMF hasn’t done its job. Why? Because of the prevailing economics dominating it. Very early in the 1960s, there was a move towards neoliberalism, and the IMF became the market defender. In today’s economy, I still can't believe it's the case where, in an official document, the IMF recommends that Nigeria – which has just introduced a new currency – should let the markets free-floatingly decide the valuation of this new currency because they know the markets would make the wisest decision. Of course, it’s crazy to give such advice, not to mention their other bad advice, which simply shows that it’s not doing its work. But if we had a critical international organization with strong powers, as UNCTAD once attempted to create with developing countries, we could ensure an actual balance. However, UNCTAD wasn’t strong enough because it had no money or industrialized countries behind it.

On the other hand, in Europe, we can see how difficult it is. I'm saying this now because, besides really annoying me, it fits here: Germany is now closing its European borders for purely national reasons without talking with its neighbors or even considering them—and without striving for other solutions, which is outrageous. This shows the CDU, a party presenting itself as Europe-friendly, hasn’t even really begun to understand what Europe is all about. I've lived in France for 25 years, and yesterday, when I drove across the border from France to Germany, there was a man with a machine gun. As a Frenchman, you have to ask yourself, ›Have the Germans gone mad now or what? Maybe they've always been crazy, but now they've gone crazy for good.‹ Nobody in Berlin asks that or has anything to do with it. They are aloof. They never drive across a border; if they do, they drive in a company car that’s undoubtedly not checked. And we repeatedly do things like that, which shows that internationalism—or the ability to act appropriately and sensibly in a globalized economy—doesn't exist in most countries. Germany, which has benefited the most from globalization over the last 20 or 30 years, doesn't understand this.

MB: Wasn't Keynes' great trick, which led to these institutions, like the IMF and the WTO, that he understood Capitalism needs something like a belief system? He personally didn't believe in gold because he understood it was a sham—that you had to put it in Fort Knox so people would feel its natural scarcity. He had the wonderful idea that the British Central Bank should bury banknotes in bottles underground so people could dig them up again and be fully employed. So Keynes created a great monetary theater which, if you follow Barry Eichengreen’s example—who wrote about the currency war problems between 1918 and 1945—was a great success because people could somehow believe in this order. Isn't our dilemma that our monetary order is no longer entirely faith-based? The mere fact that something like Bitcoin exists with all those young people who are suddenly no longer backed by gold but by electricity and the encrypted coin, which is also a belief system. But that means we have a decentralized belief system, doesn’t it?

HF: Of course, money has to do with faith. There's no question that people must believe the stupid banknote you put in their hands is worth something. And why should they believe that? Money isn’t given to them by nature, and nothing encourages them to believe it could work. Money is faith and trust. That's why you need trustworthy institutions and governments that handle it responsibly. And Keynes knew gold was a big bluff – that it was always a big bluff because it had no real function. In the 18th and the 19th centuries, it had no practical function. Yes, faith is essential for the monetary system because if people didn’t have faith, they wouldn't accept banknotes. It’s ridiculous that people toil for a whole month and then receive a few paper bills as a reward. It only works with faith. And Keynes knew that—that's why the Bretton Woods system was given a gold treasure chest in Fort Knox. But gold had no significance now or in the past. Even as the so-called gold standard in the 19th century had no real significance, it was always just a belief.

And today, you wouldn't believe how many emails I still get from people who say gold is the only way to go: ›That here in the monetary system, there must be something real, something valuable behind it.‹ No, there doesn't have to be anything behind it other than the decisive trust factor. And now Bitcoin is emerging from this story. Libertarians, who are mainly based in California – the so-called digital kings of the globalized economy – astonishingly believe there has to be something else, that it can't be the State providing the money because this money can't work—that it has to come from the creativity of private individuals. And again, that’s grandiose nonsense because there doesn't have to be anything creative about it at all. The system has to ensure banknotes are distributed efficiently; that people have liquidity in the sense of money; that there’s a banking system analyzing the funding sources; and that existing income flows. You have to have that—otherwise, you don't have to have anything else. And you don't need security. But now, crypto is replacing gold for many people because they believe it’s creating a new value hovering somewhere in the background that they need to preserve their wealth somehow—that’s a pure illusion. It's like the Netherlands’ famous tulip bulbs in the 17th century, which cost a fortune because they were said to be the most important thing in the world. That's how it is now with Bitcoin. Ultimately, it's terrible that our politicians and political system fail to educate people. We’re no longer in a phase of enlightenment, but one of dumbing down, where politicians can’t explain what’s happening or at least have people around them who can. For example, I have to say there’s no one in the German government who could explain to halfway sensible people what the debt is all about—only ideologies or ridiculous claims are put out into the world. This undermines people's trust when they feel there's no one up there who knows what it's all about – who can explain why it's being done this way and why what's happening is sensible. If people no longer have this impression, they will mentally migrate to the AfD and materially migrate to crypto. And these citizens are then out for the moment because they’ve lost trust in the system.

That's the big problem today, which is getting increasingly complicated in the globalized world – or even just the European world. Take the European world. I can’t imagine a politician who can explain what is happening in Europe, why it is happening, why it must happen this way – and what the alternative is. Outstanding politicians, such as Jacques Delors, have come close in the past, but there are fewer and fewer of them, and we can't govern a highly complex world with a layman in the chair. That won't work. I'm an old man, but I have to say that there’s too many young people thinking they can just stand up and say ›I'm a politician now, I'm the secretary general of a party or the leader of a parliamentary group or something, and I'm going to explain something to you. I haven't learned anything in this life, I haven't done anything, nor had a job, and I stand up and explain the world to people.‹ That's nonsense, it doesn't work. It's outlandish and absurd, and it destroys trust in our system.

MB: Coming back to the blockchain story, which is structurally incredibly interesting, as you could almost say it's the realization of a neoliberal project, meaning complete privatization. And then you say to yourself, okay, you're openly dealing with a decentralized currency, which is also something incredibly strange from the perspective of the Bank of England. But now comes the point that amuses me because cryptocurrency only works via this phantasm of electricity, that crypto has to be mined, that it’s a limited, finite quantity—a finite currency that becomes increasingly expensive, which is entirely pointless because a digital good can be reproduced at will. You could virtually print whatever you want. Why do we have to have the ghost that the thing is scarce? Here again, we see an absurd theater where people believe something is scarce because it’s been artificially made scarce.

HF: Yes, of course, the whole idea of crypto is nothing other than gold...

MB: Yes, exactly, an electrified gold...

HF: Gold is limited, so there can be no inflation; that's nonsense! There can be any amount of inflation, but people need this because they're not enlightened and have the wrong idea about money’s relation to prices. None of that works, and it doesn't work because we can't explain it. If there's one thing people believe in, it's the Deutsche Bundesbank. For decades, the Bundesbank has confused people. It’s preached monetarism to them, which wasn’t justified by anything. I'm sure there were enough people in the Bundesbank who knew this. Nevertheless, they told people this because they believed they had to tell them there was a mysterious money supply that stabilized the Bundesbank.

Crypto is nothing other than a money supply limited by a clever technology – not some technocrats like the National Bank, and that’s the only brake helping save the world's financial system. This is fantasy; there is no connection between these sentences and ideas, but people want to believe it because they are unenlightened and still don't understand a monetary system. It has taken decades to explain to people what Schumpeter stated in 1905, namely that banks create money. Of course, the banks create money, which is entirely unproblematic because they generate money within a framework already controlled in some way by the Central Bank and the economy’s overall credit development. This is completely unproblematic; there hasn’t yet been a bank that’s somehow caused an explosion through credit creation, but for many decades, it wasn’t allowed to appear anywhere that the banks created money. If you create a currency in quotation marks, such as a stable coin, then there’s nothing behind it that could pay interest, just hot air. And then, at some point, it goes down the drain. There is a beautiful project in Korea where someone founded Luna and Terra, which are lovely coins. They blew up very quickly. Why? Because it didn't work. At some point, people realized, ›Why should I hold Luna and Terra if all I get in the end is dollars, nothing comes out, and I can't get any interest?‹ Then, some guy offered 20 percent interest on holding Luna. You could buy Terra with Luna, but then he went bankrupt a short time later.

MB: We’re at an age where we can probably state that there’s been an incredible loss of confidence as a biographical phenomenon. And if we look at the 1970s and ‘80s investment activities, a good third of Germany's gross national product was invested in the future. This amount has more than halved. This is reflected in the fact that no relevant future projects are being tackled. You can see it in the streets, the decaying education system and the schools of thought that indulge in resentment or are, at best, able to chant: Great Again! Where do you think this obliviousness to the future comes from? How is it that the time horizon of our economic and political elites hardly covers the next generation, regardless of sustainability trends, while often ending with the following quarterly report or the next election?

HF: Yes, indeed, this short-termism, which starts with the quarters, is indeed quite fatal. That came about with the ‘80s stock market hype. When you just have to be successful per quarter, you don't have to be successful in four years. That led to a lot of terrible developments. Shareholder value was the keyword, which is nonsense because shareholder value always comes out in the end. Still, it depends on how I produce shareholder value, meaning how I increase the company's value. This has led to dangerous short-termism in corporate behavior. Of course, in politics, on the other hand, we stopped pursuing sensible economic policy and sensible management—both simultaneously, especially in the 1980s – astonishingly, when the neoliberals took over for many reasons. One reason is that we constantly had interest rates that were too high because of monetarism, as we’ve already discussed. The other reason is that we then systematically exerted pressure on wages, which was fatal. In a market economy, wages must always rise in line with productivity without much discussion, fighting, or anything else. One of the most important tasks of a government is to ensure that this works and that there’s no stupid fake battles between employers, employees, location policy, and the like. These have all been monumental mistakes. Then, the bridge collapsed in Dresden. I can tell you who is responsible for that—not in Dresden but for the other bridges.

MB: And who would that have been?

HF: Mr. Kohl is responsible for the other bridges. He’s the main culprit for this privatization mania, which involved cost-saving without making any more sensible economic policy. This intellectual and moral turnaround has led Germany into the abyss. Mrs. Merkel continued to do so without a second thought. That was 16 years of total lack of standards, and unfortunately, it hasn't gotten any better. However, we must achieve this turnaround by sensibly discussing debt and investment. How does it help future generations that we have no debt, but the bridge has collapsed? So that's obvious nonsense. If we don't get our act together, we will fail, and Europe will fail. There is slashing and stabbing, and that is also down to the personnel, very much down to the personnel. Unfortunately, I have to keep saying that. You can't just put random people in Brussels and at the head of the Commission. I don't want to mention the lady's name now, but everyone knows her. It would be best to have people with ideas like Delors, whom I’ve already mentioned, and Juncker. People who embody something, have visions and can drive the whole thing forward—while also having realistic insights into the processes—and not political bumblers who sound off every day about doing everything or nothing without any ideas, depending on what suits them politically. That can't work, and we’re suffering greatly from that. I was just in Italy this weekend to give a lecture in Rome. There’s no discussion between Italy and Germany. The foreign minister who spoke after me was very excited about monetary policy, which is good, but there must be communication channels. He stands up in a large business meeting and gets upset about monetary policy. He had good arguments, but that's not the forum or the way to discuss them. And they don't want to hear anything about Germany because they've simply had bad experiences in recent years. And you get the feeling, you notice it: Europe is melting between your hands. You try to grasp it, but it's no longer there. And that isn't good.

MB: We’ve replaced a political economy with a moral economy, which you see in the moral grandstanding with the simultaneous absence of economic reason.

HF: We need rationality. And more and more, that’s being lost. We do all sorts of pipifaxing, genderism, or whatever it is. You can do anything except lose the rational debate. And that gets lost. And that's where it gets critical.

MB: After all, you are one of the – incidentally not very numerous – representatives ascribing a significant role to the State in economic activity. Of course, the question arises as to whether – and to what extent the players have understood the laws of relevant economics. Let us study this using a very specific case. Our Minister of Economic Affairs, Robert Habeck, has realized that the market will not try tackling the much-discussed energy transition. So, he is looking for an economist to provide him with the appropriate model for action. He finds Mariana Mazzucato, who asked herself what the miracle of digitalisation is actually due to. ›How did something like the smartphone, a technology nobody could have imagined a decade or two earlier, come into the world?‹ So she goes back into the history of digitalisation and says, ›Well, it was all the money that made things like GPS, the Arpanet, and the like possible as with State-funded DARPA‹ So Robert Habeck says, ›Let's do it exactly the same way. We’ll set the direction, provide the money, and at some point, the miracle of disruption will happen – what was a one-of-a-kind thing will suddenly scale up.‹ Where’s the mistake in thinking here?

HF: Yes, it's a nice idea, but I'm certainly the last person to deny the State plays a big role – and it can also play a significant role in technology. It’s driven many things forward through military developments, space research, and other things; there's no question about that. We need an active, competent, and proactive State, not necessarily a large State, but an intelligent, competent State that knows its tasks and drives them forward. Of course, this also applies to climate change and the environment in general. But it's no use spreading activism; unfortunately, that's what Mr. Habeck is doing. We’ve lost the big picture in the climate debate, where the big picture means ›I have to go global.‹ It’s no use toiling away here while nothing actually happens globally.

MB: As absurd as I find the political argument behind the Mariana Mazzucato analysis, the argument itself is interesting. I’ve written a History of Digitalisation, and if you follow not only the handling of information but also the very energetic question of transistor development as it happened in the 1950s, you’d have to say it was an incredibly productive time of development. Think of solar panels – the solar-powered radios you probably know from childhood were a transistor by-product. If you ask yourself, did the whole world really do that? No, it was specific, small groups of people who gradually developed things over time—with the effect that today, every person with a smartphone in their hand has more information capacity than NASA had available when they shot their astronauts to the moon. That is an incredible explosion in productivity...

HF: No, that doesn't help if he doesn't know what to do with this information...

MB: Exactly, but he can do that too.

HF: He has to be guided; someone has to tell him what to do with this information. People look stupidly into their devices and look and look and look. And when they find something important, that's incredible information to have in your hand...

MB: But wait a minute, I agree that these things aren’t there for their own sake, and they’re even meant to extend our minds; that’s absolutely correct. But the interesting phenomenon here is that the State didn’t initiate these things, but disruptions unfolded—and not even the players involved knew precisely where it would lead. Here, we see this series of Schumpeterian disruptions that are almost anarchic, which, if I wanted to play a very regulatory role, should have been tamed to benefit th common good. As an exemplar, you could say to yourself, ›Okay, if everything x=xn can be reproduced in the digital world without marginal costs‹. You could then say to yourself, ›Okay; I could imagine and build the coolest education system ever because I can spread it across the whole World: Anything, Anytime, Anywhere! I can literally give it away!‹ But the point is that we don't see any monetary investment in this world. We see stupidity being cultivated. By the way, data protection is a technique for not having to alphabetize yourself so you can continue cultivating your stupidity—meaning if you get involved in this digital world, you’ll gain something, but if you don't, you won't.

HF: Yes and no; AI is now the attempt to overtake our limited brains in the digital world. Let's see how far it goes. So far, what you can retrieve is just an average opinion...I've tested it a few times, and after two queries, it always comes back that the system is dead because it doesn't know what to do when you ask intelligent questions that aren't easy to answer. So far, it's not very impressive. But maybe this is a first attempt, and perhaps we're getting smarter about AI. I doubt it, to be honest. In the end, humans are the limiting factor, and AI always has to pass through our brains. If it doesn't, it doesn't go anywhere—or we all become zombies.

MB: Let's hope not.

HF: So it has to get through our brains, and that's why it doesn't help. We have to train our brains. We must put our children in a position to deal with and understand it. And we don't do that enough. We need to provide a much better education. But education can't mean looking at a stupid computer or that everyone has a laptop in the classroom. That has nothing to do with thinking—we have to learn to think critically, and we have to learn to reason again. We were a bit further along with rationality in the past. So, we must return to the Enlightenment Ideal, where people approach problems rationally and learn to solve them sensibly. The digital world will help us a little but certainly won't solve the problems—we have to do that ourselves. Unfortunately, I don't see the willingness or recognition of the need to spend much money on that. I think more money for education is essential, but not blind digital education now, à la the Nuremberg funnel. We need real education and training in thinking. Then, perhaps we can take a step forward. But we're weak in that area, too. I think Asians, for example, are much better than we are.

MB: If, despite your advanced age, you were to sit down and sketch out the science fiction model of a functioning digital Capitalism that you—as you so beautifully put it—were responsible for running – what would that look like?

HF: I have just written that down. In my book, I gave a blueprint of how it could work, at least for the economy, not society as a whole, but for the economy. I don't want to solve everything, but I have just made a draft for the economy. Let's see where and whether it leads to a sensible discussion. That is the big question. And in the end, everything will be decided by these questions.

Translation: Hopkins Stanley and Martin Burckhardt

See Flassbeck, H., et Al. – Economic Reform Now: A Global Manifesto to Rescue our Sinking Economies, London, 2017.

See, Flassbeck, H. – Grundlagen einer relevanten Ökonomik, Frankfurt, 2024.

See Hesse, H. – Das Glasperlenspiel, Switzerland, 1943 [Magister Ludi – The Glass Bead Game, trans Richard and Clard Winston, 1969.]

See Schumpeter, J. – History of Economic Analysis, London, 1954. Schumpeter hadn’t finished editing this work before he died, but his third wife, American economic historian Dr. Elizabeth Boody, who had assisted him in researching and writing the work, finished its editing and posthumously published the work

See Schumpeter, J. – Theorie der Wirtschaftlichen Entwicklung, 1911 [The Theory of Economic Development: an inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle, 1934.]

Related Content

Capitalism - Dead or Alive?

Der Kapitalismus ist tot (Er weiß es nur noch nicht) was published in 2018, the same year as Philosophie der Maschine and Eine kurze Geschichte der Digitalisierung, and is the fifth in the series of Martin’s New Works. Although audible only as background noise in Martin’s earlier works, the debate with Marx was omnipres…

Talking to ... Jeff Sutherland

Looking at many contemporary institutions, we can't help thinking Modernity's secret goal lies in its organizational irresponsibility. In the shadows, however, a revolution has occurred where the individual doesn’t have to function as a cog in the Wheelwork of a

Im Gespräch mit ... Thomas Mayer

Wenn es in der Ökonomie den Konterpart des Kriegsphotographen gäbe, so könnte man Thomas Mayer einen ›Physiognomen des Crashs‹ nennen, nicht zuletzt auch deswegen, weil seine Biografie ihn mehrfach ins Auge des Sturms hineingeführt hat. Nach dem Berufseinstieg ins Kieler Instituts für Weltwirtschaft gelangte der junge Volkswirt zum Internati…

Life in the Attention Economy

What makes Quota is the second text in our new series of Martin Burckhardt’s later writings. First appearing in the December 2017 issue of Merkur, this essay falls between 2015’s Alles und Nichts:Ein Pandämonium digitaler Weltvernichtung and 2018’s Philosophie der Maschine