Dear Ladies and Gentlemen,

I want to share a few thoughts with you on the peculiar relationship our society has with Artificial Intelligence. It confronts us with the uncanniness of how it’s taken on an almost religious-like quality—why else would the phrase curse and blessing instinctively come to mind when talking about it? To make sure the ideas I present to you are not completely out of touch, I would like to share a few video clips we’ve published on our ex nihilo Substack, created in collaboration with Dall-E and Google VEO using our in-house, proprietary Company Machine. This software is quite unusual insofar as it transliterates classic essays and transcribed conversations into visual metaphors, and because our brain—or more precisely, our language—is a veritable magic box, these produce the most daringly audacious image compositions—things that even the most fantastical mind could hardly conceive. In a curious way, a remarkable reversal can be observed here. When we talk about the power of imagination, when some extremely daring theorists of the 1990s conjured up as the visual turn, it must be said that advanced image production had long since left the visual sphere—and gone to our heads. This is noteworthy as we are witnessing the return of a medieval concept of Signs. At that time, it was believed that the closer a Sign was to God, the more valuable it was – or, as we would say today, the more abstract it was. Consequently, thought was considered the most valuable Sign, followed by the spoken word, then the image, and finally the worldly traces one leaves behind. This changed with the Renaissance, which actually brought about the visual turn that cultural theorists of the 1990s diagnosed with considerable delay – and Leonardo da Vinci reflected on the fact that music is the little sister of painting, simply because it fades away, while painting releases works of eternal value into the World.1 So today, while claiming we live in a visual culture may still appear to be true for large parts of the population, the intellectual and aesthetic drive that feeds this world has shifted its metamorphic form. If Hollywood’s dream factory went on strike recently, it’s because the advances in our computer culture are truly revolutionizing filmmaking. You only have to think back to one of those epic historical films of the 1950s and 1960s, where entire small towns in southern Italy were recruited as extras – and you see the difference. Today, CGI (computer-generated imagery) provides directors with a whole armada of hyper-realistic, malleable actors. And this rationality shock affects not only the extras, but also the set and stage designers, as well as the musicians, whom Bernard Hermann once invited to the recording studio in the form of an entire symphony orchestra. All this is now accomplished by someone like Hans Zimmer or by anonymous CGI artists who conjure up the most phantastical things on screen, which means that what used to be called a set is now little more than just a studio warehouse where a few actors perform in front of a green screen. Now, this threat of rationalization posed by Artificial Intelligence affects not only the immediate production process but also post-production. Today, when voices can be cloned at will, and even translation and dubbing can be done by AI with perfect lip synchronization, the radical revolution of the dream factory is a fait accompli.

Now, I could launch into a dystopian tirade about the changes to our audiovisual tools—and I would be justified in doing so, insofar as the coming surges of rationality are likely to affect the entire industry. But that is not what I want to do right now. Why not? Well, simply because I am convinced that a) this is a matter of inevitability, and b) well, I personally find the aesthetic and intellectual possibilities opening up with this world both sublimely wondrous. The dilemma we face is more intellectual, if not philosophical, in nature—a humiliation that surpasses anything Sigmund Freud recorded in his Civilization and Its Discontents. As you may recall, he identified three intellectual humiliations: 1) The Copernican Revolution, which meant we could no longer feel like we were the center of the Universe; 2) Darwinian Evolutionary Biology, which called our Anthropological Supremacy into question; 3) The Subconscious self, which made it clear to individuals that they cannot even feel at home in their own thoughts, that they are no longer masters in their own house. Now, let’s keep in mind that when these upheavals happened, they only really affected a small number of people (the so-called elite, if you will), but with the Digital Revolution, we are now facing a new and much more serious situation: it impacts everyone, absolutely everyone in this World.

The dilemma we face today can best be compared to what Günter Anders once aptly called Promethean Shame—which can be understood as a form of schizophrenia: I am, but I am not. If Blaise Pascal once said that all human unhappiness stems from the fact that humans cannot remain quietly in their rooms, then it’s evident that networked humans are, by definition, social creatures—or, as I would put it: dividuals who thrive on their divisibility and their urge to communicate. But because that sounds so harmless, I will tell you, who are largely familiar with the practices of our public broadcasters, a little personal story. It has to do with how, as a young man, I couldn’t quite decide whether I wanted to be the next Thomas Mann or a composer. In any case, I realized quite early on that the heroic history of the modern author belonged to the tempi passati. That was in the mid-1980s, and since I had been working with a musician from Tangerine Dream for many years and was deeply involved in the world of recording studios and electronic sound processing, I eventually realized that some unquestioned fundamental assumptions had exceeded their shelf life. When you have a sequencer in front of you that allows you to chase your fingers across the piano, or more precisely, the keyboard, at unprecedented speeds, you wonder why you ever bothered with scales and Czerny’s School of Velocity. Even deeper than this doubt about virtuosity was the discovery that, with sampling, the whole world had actually become a musical instrument, that even the sound of a toilet flushing could be a great aesthetic experience, not to mention that a sampled sound is actually a multitude, a multiplicity. In short: What caught my attention was nothing other than the threat of proliferation posed by digitalisation.

Fast forward three or four years, when I conducted an intensive seminar at the University of the Arts together with an editor from the RBB [Berlins public Radio], where I was working, and Johannes Schmölling, the musician from Tangerine Dream, during which we prepared actors and sound engineers to work together—and because it was going to be broadcast, this wasn’t just any ordinary practice session, but the real deal. And then my colleague from the station, Wolfgang Bauernfeind, had the idea of showing the sound engineers how the professionals at the station work. But since I had worked as a director in large companies and knew that the sound engineers weren’t even willing to touch the multi-track machine in the studio – whereas the studio at the University of Fine Arts was already fully digitalised – I told him that wasn’t such a good idea. But he insisted – and so, at some point (it was around 1992), half a dozen sound engineering students entered the hallowed halls of the station, the T5. But after just fifteen minutes, barely had the professionals begun their work, the first student came up to me and whispered in my ear: »Tell me, Martin, are they serious? « Which was, of course, a very valid question. At any rate, a few years later, I ran into one of the sound engineers in the station hallway, who asked me if I thought someone like him would be employable in the private sector.

Where does this resistance to engaging with this world come from? The answer is simple: people resist because the experiences of engaging with these new tools seriously shake and disrupt their self-image. And most people prefer the phantasms of the past to such an uncertain, unsettling future. Consequently, they talk about true authenticity, about digital detox, or, when their attempts to assert digital sovereignty fail, they proclaim the end of humanity: the Infocalypse. Why is all this so easy? Because Artificial Intelligence, like an alien, imposes itself as a foreign body – for the simple reason that we’ve never really embraced the World of Digitalisation, or at best only as consumers who press buttons. Let me tell you a little story about this. While traveling across the US in the late 1980s to interview the pioneers of Artificial Intelligence, I had a lovely encounter with Joseph Weizenbaum, the great-father of all chatbots, who told me – still shaking his head – about his secretary.

And because she was assigned only to him, she naturally knew that Weizenbaum was working on a chatbot named Eliza – a tribute to Eliza Doolittle from George Bernard Shaw’s play Pygmalion – and she also knew that this chatbot was nothing more than a program that Weizenbaum had written using the computer language LISP. In fact, the program wasn’t particularly sophisticated, essentially little more than a paraphrasing machine. As an exemplar, if you typed in ›I feel bad,‹ the chatbot would respond, ›Oh, you feel bad?‹. What astonished Weizenbaum was that whenever he saw his secretary, she was constantly clattering away on the keyboard—so intently she didn’t even notice him coming. And because he was curious about what she was actually typing – she didn’t have that much to do for him – he stepped behind her one day and glanced at the screen. And what did he see? That his secretary was using his chatbot as a substitute psychotherapist: »I feel bad« – »Oh, you feel bad?«. This discovery intrigued him immensely—he realized that, despite his secretary’s knowledge that she was communicating with a simple program and not a human being, Freud’s mechanism of transference was at work here.

While we might smile at this story, the strange part is that many of our peers indulge in similar behaviors—and that this form of transference (thinking of Ray Kurzweil, who dreams of a superintelligence) doesn’t even spare the experts in the field. This observation deepened my exploration of cultural history—an endeavor that ultimately resulted in the writing of several books. Throughout my research, I’ve kept asking myself the same question: How did this come about? What exactly is a Machine anyway? What makes people imbue machines with metaphysical, often religious significance to machines? But before we venture into the question of what we really mean by Artificial Intelligence, let me offer a very simple, albeit unusual interpretation of the computer world. What makes it so unique? As a young author, what was it that fascinated me about the World of Sounds? You could say it was this: Whatever can be electrified can also be digitalised. This means: What we call Writing is no longer just an abstract idea floating above the waters like the mind of God (or the Letters of the Alphabet), but can take on any imaginable form. This could be the geo-location data of a whale, the sound of a toilet flushing, or the swipe-away gesture of a hand that city dwellers use to reject potential partners they definitely don’t want to get in bed with. Applying this logic to the Work World, which is the only one we value, would mean that any Work that has been digitalised ends up in a Museum of Labour. Here’s another memory from the early 90s: a wonderful pianist came into the recording studio, played a piece by Schumann, and then left. But no sooner had he left the studio than the grand piano, which had stored his finger movements via MIDI sensors, played the piece again—and if we had wanted to, we could have sat down with Cubase or Pro Tools and altered his performance at will. And this raises the question: What does it mean that every piece of work that has been digitalized disappears into the Museum of Work? The answer is simple and familiar to us all. Because electricity transcends distance, the program—in other words, the mummified work process—can be transplanted and accessed from anywhere in the world: Anything, Anywhere, Anytime. Haunting us here is the dilemma of the Speed of Light. And this has nothing to do with Artificial Intelligence. Let’s take this a step further by examining the basic formula of our digitalised Continent of the Mind more closely. It can be found in an 1854 work published by English mathematician George Boole. Although it underpins Boolean algebra and logic, and every programmer uses Booleans routinely, this formula remains a terra incognita. Try it out the next time you get the chance, and you – or, depending on who you’re programming with – will experience the surprise of a blue miracle. And you don’t even need to venture into higher spheres to do this. George Boole, who pursued the project of »removing the representative from mathematics,« asked himself a very simple question: What do zero and one, the two royal numbers of mathematics, have in common—and what sets them apart from all other numbers? If I multiply one by itself, the result is always one, and if I multiply zero by itself, the result is always zero. This distinguishes zero and one from all other numbers. Formalising this gives us the basic formula for everything digital: x=xn. If you retranslate this back into natural language, you might begin feeling vertiginous: because it means the end of the original, the end of identity, the end of authenticity. Taking this seriously and applying this formula to yourself, you would have to say: I am someone else, I am superfluous, I am a population. The extent to which this logic has already taken hold of our thinking becomes clear when we consider that every digitized object (be it a .pdf document, an audio, or a video file) is structurally superfluous. This, it seems to me, is a profound upheaval, the consequences of which we cannot yet fully foresee.

Let’s take this a step further and consider Artificial Intelligence, which is really more like pseudo-intelligence. Because what we see staring back at us in the mirror is, literally, a »mediocre« version of ourselves. Let me briefly digress to The Man of the Crowd, a short story published by Edgar Allan Poe in 1840. What prompted Poe to write this short story, whose motto intriguingly references the misery of human beings (Ce grand malheur, de ne pouvoir être seul – the great misery of not being able to be alone), was his reading of a text published a few years earlier by computer pioneer Charles Babbage: The Ninth Bridgewater Treatise. – This is the same man who founded the Royal Statistical Society and whose Analytical Engine, the precursor to the computer, rendered 10,000 French calculation slaves jobless. Indeed, Edgar Allan Poe’s hero, who watches passers-by from a London café, acts like a statistician—classifying workers, small clerks, cleaning ladies, maids, and so on. But when an older man moving in a strange, unpredictable way catches his eye, his curiosity is aroused. He gets up and begins following him. In this chase, which reads like a crime thriller, the narrator realizes that this man has lost his inner center of gravity—he is almost magically drawn to the events happening around him. This is the secret that is finally revealed after a long pursuit: this man has lost his center—and because he is off-center, he is completely absorbed in society and the world around him. This insight comes as a shock to Edgar Allan Poe’s narrator:

»»This old man,« I said at length, »is the type and the genius of deep crime. He refuses to be alone. He is the man of the crowd. It will be in vain to follow; for I shall learn no more of him, nor of his deeds. The worst heart of the world is a grosser book than the ›Hortulus Animæ,‹ and perhaps it is but one of the great mercies of God that ›er lässt sich nicht lesen.‹« [he cannot be read]

When we enter text into ChatGPT or Claude.ai – or generate an image using Dalle-E, Flux, or Stable Diffusion – what comes out is our stochastic self, The Man on the Crowd. And while this may appear intelligent – and even more intelligent than what entire cohorts of undergraduate bachelor’s students put on paper – it has nothing to do with true intelligence. You get the answers, or more precisely, the patterns that machine learning, with the speed of light of processors, has been able to find and collate from its database. In other words: what we see staring back at us from the mirror is nothing other than this Man in the Crowd. Once you realize that even talking about Artificial Intelligence is a kind of self-deception, the more interesting question arises: How do we deal with this so-called intelligence? And how do we escape the dilemmas that are epitomized in Edgar Allan Poe’s depiction of The Man of the Crowd: the archetype and the genius of deep crime? The answer is both simple and difficult. Simple because this demon loses its power the moment you become aware of it. Difficult because, as a society, we have long since entrenched ourselves in particular forms of social schizophrenia. This is evident in how people don‛t find it strange to want to limit Internet free speech by invoking digital sovereignty inspired by Carl Schmitt‛s thinking. Calling this intellectual confusion cognitive dissonance is almost an understatement, as it seems to me far more dangerous than anything we fear accomplishing with Artificial Intelligence. Yes, creating avatars of ourselves that act as consumer influencers is possible—but this idea has been entrenched in people’s minds long before it became a technological reality. When the call center agent recites his lines from a script, then I’m no longer talking with a human being, but with an android. It’s easy to forget where certain concepts originated. Take the cyborg, for example. In the 1960s, this term was used to describe humans who could only be kept alive in hostile environments—like the vacuum of space—by cybernetic means, turning them into cybernetically enhanced organisms. Viewed in this light, all of us who are glued to our smartphones and computer screens have long since mutated into cyborgs. Is there anything wrong with that? I would say no—or if there is anything to be said, it is that being a cyborg conflicts with claims of Identity, Authenticity, and Digital Sovereignty.

In conclusion, I can certainly see that digital disruption, along with the advent of machine learning and AI, represents a major paradigm shift – and the political consequences could be as profound as the arrival of the Wheelwork Automaton, which plunged the Middle Ages into a veritable crisis of faith. You see it everywhere: a kind of general unease in culture that, in order to assert itself, takes refuge in an eroticism of resentment, a Great Again that seems like postmodern Quixotism: a fight not against windmills, but against processors that, just like Don Quixote, appear to us as monsters of the past. No philosopher captured this dilemma better than Nietzsche when he wrote:

»Those who fight monsters should be careful not to become monsters themselves. And if you stare long enough into an abyss, the abyss will stare back at you.«

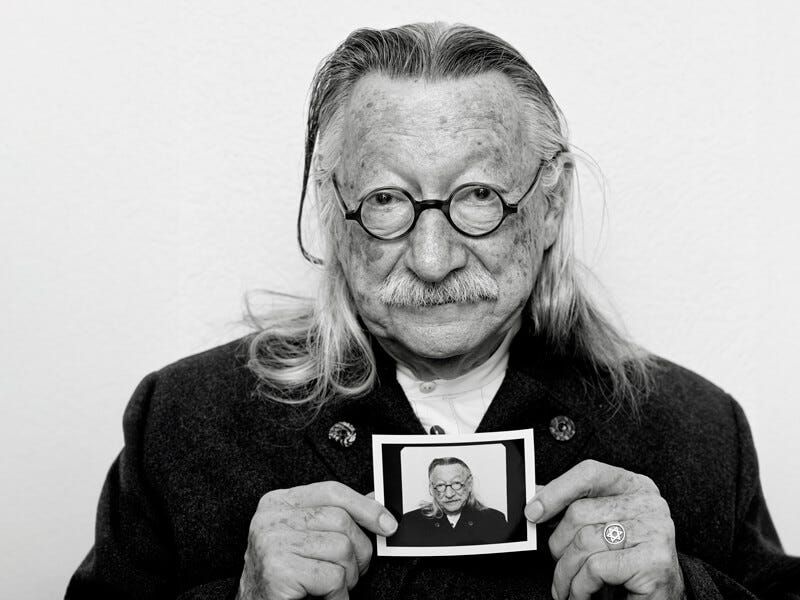

If I ignore all these political questions and focus instead on what could be achieved with AI today, especially in the intellectual and aesthetic realms it opens up, the scenery changes radically—just as its pitch suddenly shifts too. Maybe we’re venturing into territory that’s unfamiliar, if not downright frightening to us in its uncanniness. For my part, I wouldn’t settle for anything less than what the Renaissance did for our culture because the Realm of Signs (see above) is once again undergoing a radical revolution. Anyone who works with audiovisual objects these days could probably tell you a thing or two about this. Immersing yourself in a program like DaVinci Resolve—what an apt name!—suddenly raises questions about the effect of a sound file on color or lighting design; or you find yourself preoccupied with the aesthetics of light leaks, glitches, particle emissions, and so on. All these questions may seem as obscure to you as how my reflections on the Philosophy of the Machine led me to Alien Logic—and I don’t blame you for that, quite frankly. When my son, as a 9-year-old Waldorf school pupil, was asked what his father does, he replied charmingly: »My father writes books that nobody understands!« The point is simply this: all the convictions I have arrived at over time are not inventions of my own, but have to do with the Social Drive that affects us all.

With this in mind, I thank you for your attention.

Translation: Hopkins Stanley & Martin Burckhardt

›Music may be called the sister of painting, for she is dependent upon hearing, the sense which comes second...‹ in his Treatise on Painting. See Da Vinci, L. – Trattato della pittura [A Treatise on Painting], eds. Rigaud, J.F. & Brown, J.W., London, 1835.

Related Content

Alien Logic

The following is the visualization of a lecture Martin gave on May 11, 2021, at Vienna's IWM, where he spent a few months as a fellow in the spring following the publication of the Philosophy of the Machine. Because this lecture is a tour de force pulling together his previous thinking as a prequel to his five-book series, the

Cyborg Psychology

One of the peculiarities of the Artificial Intelligence Discussion is this conviction that it's only about replacing the human being, while there's hardly a thought given to the fact that what we've put into the world is nothing other than a magic mirror reflection of ourselves- and that this instance will necessarily change our self-image as well.