How to ride Windmills against Windmills

A Conversation on the Failure of the German Energy Transition

Introduction

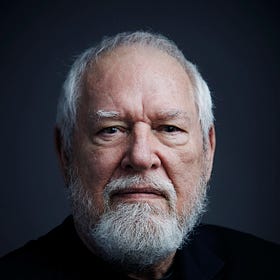

As we’ve known since the French Revolution, the revolution not only eats its own Children1 but also its Fathers. With this in mind, it is easy to understand the career of Fritz Vahrenholt, whose bestseller Seveso ist überall [Seveso is Everywhere] in the late 1970s made him the intellectual catalyst of the new environmental movement and provided his clear and practical impetus as a long-serving senator in Hamburg before going on to establish the first solar roofs and offshore wind farms as a manager for large energy companies. But surprisingly, this man has now been given the dark aura of a climate denier. Why? Has he been canceled because he doubts the rationality of the climate movement, questions the economic rationality of Germany’s energy transition, and brings the practical small print details of science to the fore: namely that a wind power plant in Bavaria only delivers 12.5% of the power that its counterpart in the windy north of the country do - making the construction of such a plant completely uneconomical? It seems that anyone who violates the pure teachings of ideologues must expect sanctions, which is a lesson that Soviet-style communism has demonstrated time and time again - resulting in Mao Tse Tung's re-education strategy: Punish one, educate hundreds! Once the Cultural Revolution’s effectiveness of such behavior has been demonstrated, the question arises: How do you violate the pure teachings of the environmental movement - and what do they consist of? And if these measures aren't carried out by ordre de mufti, then who are the propagandists of this cultural revolution? The only plausible answer to this question is that the spirit of utopia, confronted with the failure of its ideal, develops a certain amount of resentment - and this resentment needs a scapegoat to be released. Considering the German energy transition project, which was launched with great aplomb, it is clear that all attempts at putting it into practice could only end in complete failure. And because there's nothing more terrible than the collapse of this grandiose fantasy, people are holding themselves harmless against those they believe to be responsible for it failing - bringing the movement's forebearers into their sights. In this case: Fritz Vahrenholt.

Vahrenholt was still considered darling des feuilletons in the 2000s until he became a victim of the Climate Activist movement’s devolution into apocalypticism. After resigning from his energy manager position in 2012, he became the German Wildlife Foundation’s honorary President until 2019, when he criticized the German government's climate policy by reminding MPs that a net-zero target for global CO2 emissions is not required for all – and the Foundation's Board decided they couldn’t afford such a president. Consequently, Vahrenholt, who’d campaigned for the living conditions of the red kite, Eurasian jay, Gareten's dormouse, and the golden jackal like the Foundation members, was removed from office, according to the press release, primarily because he had differing ideas about the foundation's positioning in the current climate policy debate. The calculus was elementary: Vahrenholt's publications had earned him the stigma of a climate denier, and the Board members wanted to absolve themselves of any guilt by association. Curiously, this club dispute seemed like a portent anticipating the cracks in the green worldview, suggesting that behind much of what masquerades as environmental protection lies a gesture of self-empowerment, even a quasi-religious belief - and because this can’t be based on a principle of reality, it requires this negative identity: the denier, the indulgence, and the apostate. It's not surprising that this religious war is reaching its climax at the very moment a Green government can implement its ideas on the energy transition – because it's here that the very specters leading to the Green Party’s founding are now emerging and making themselves felt. If we consider the emergence of the German environmental movement at the end of the 1970s, several historical currents come together here: On the one hand, the Greens became the catch-all for a left that had lost its place – while it also offered a field of activity for traditional environmentalists (some of whom also wanted to redeem themselves from their National Socialist past). At the same time, because of the awareness created by the Club of Rome reports, the idea of sustainability was in the air – and it was no wonder that the zeitgeist began turning green almost of its own accord. Although many forward-looking perspectives were opening here, the movement's amalgam consisted essentially of a civilizational criticism in which a left-wing, Marxist-inspired critique of the system was combined with a diffuse sense of alienation. While conservationists were appalled by the environmental damage (for which there were definite practical and tangible reasons), there was also massive skepticism about the system. This was evident in the 1984 German census when a modest suggestion from demographical analysis provoked hysterical reactions and painted a terrifying picture of a Big Big Brother digital surveillance state. As a result, the first Green parliamentary group, just elected to the Bundestag, put up posters in their offices declaring they wouldn't work with computers and were against the computerization of ordinary citizens. This anti-authoritarian impulse has turned into an authoritarianism, eclipsing all previous government initiatives. As Nietzsche aptly put it in his aphorism Against the Fantasists: The fantasist denies the truth to himself, the liar only to others - he makes it clear that the phantasm has nothing to do with reality, but all the more with one's self-image – or to use a contemporary term: the phantasm is a form of identity politics. If the revolution, as in Vahrenholt's case, now eats one of its spiritual fathers, it is because the idea of purity, benevolence, and the affirmation of nature ultimately represents a formula for self-empowerment that's shattered by reality. And because the admitted self-deception would amount to a narcissistic humiliation of the first order, the critic is fought in the strongest possible terms. That’s precisely what makes the conversation with Fritz Vahrenholt a lesson in how practical reason (environmental protection) has been sacrificed to self-empowerment and a resentful ideology.

– Martin Burckhardt and Hopkins Stanley

Im Gespräch mit ... Fritz Vahrenholt

Speaking with Fritz Vahrenholt

Martin Burckhardt: I'm very much looking forward to today's conversation, even though we're entering dark territory with the issue of impending German deindustrialization. But I suspect you’re already used to quite a bit of headwind in our heated political climate. If taken biographically, it’s strange that – like André Tess, who should have been the poster boy of the energy turnaround, or Roger Pielke Jr., who was ennobled as the Lord Voldemort of climate science – you too were an environmentalist from the beginning. In 1980, I still remember in your book Seveso is Everywhere2, you used the example of a terrible chemical accident to raise awareness of the need to protect the environment. And that was probably one of your reasons for serving as Hamburg’s Environment Senator from 1991 to 1997. What’s in your background that moved you to take up this issue?

Fritz Vahrenholt: I majored in chemistry quite successfully, and then I had the opportunity of working in environmental policy at the Federal Environment Agency3 when Germany wasn’t ecologically in a good state. We tend to forget that, in the 1980s, we still had fish dying in rivers and were plagued by waste scandals. In the early years of my senatorship, I still remember having to sound the ‘Smog Alarm’ because the air was so poisoned. As a chemist, I came into this period realizing things were not okay – chemistry significantly contributed to that situation. For example, the poisoning of rivers essentially stemmed from chemical industry wastewater. And I put my finger on that wound, which helped the chemical industry make a 180-degree turnaround, becoming an environmental policy pioneer. Today, you can swim in the rivers and eat the fish – and we have clean air, so those environmental problems I worked on as Environmental Senator were effectively solved; then another issue came up in the 1990s: CO2 pollution – the possibility of climate change, and today...

MB: Stepping back…you grew up in the Ruhr region, which in my childhood was notorious for its pollution. Women had to wash their curtains weekly, only to find them dirty again a week later. Did that play a role in your becoming an Environmentalist?

FV: Yes, I'm from the Ruhr area and was born in Gelsenkirchen – and, of course, I remember exactly how dirty the laundry got when it was hung out in the garden to dry. I still remember experiencing that smell of the Ruhr area – this dusty air full of sulfuric acid. I still experienced it in the 70s when I’d visit the Ruhr area, realizing I was back home when I’d breathe in that air – but that’s over. You may still remember Willy Brandt's saying, ‘The blue sky over the Ruhr’? That was a political goal I grew up with, and I was so proud that when I resigned as Senator in 1997, I could say, ‘…but things are done, the Elbe is clean again, the waste scandals are gone, the air is as clean as it is in the forest – and we can put things to bed now’. But as I said, a new overarching issue that marginalized environmental policy emerged. Because, of course, issues like biodiversity and conservation efforts are now being challenged by the energy transition, like the ecological destructiveness of wind turbines in forests. So, there was a total paradigm shift in the 1990s. People no longer worried about the daily environment; the issue became climate protection.

MB: You’re talking about something very tangible. You go into the garden, you see and feel the smog, you smell the pollution - and then suddenly comes the moment of abstraction, and it's only in this Augenblick that it becomes a topic or a theme emotionally moving people in the way many things do…how can you explain that?

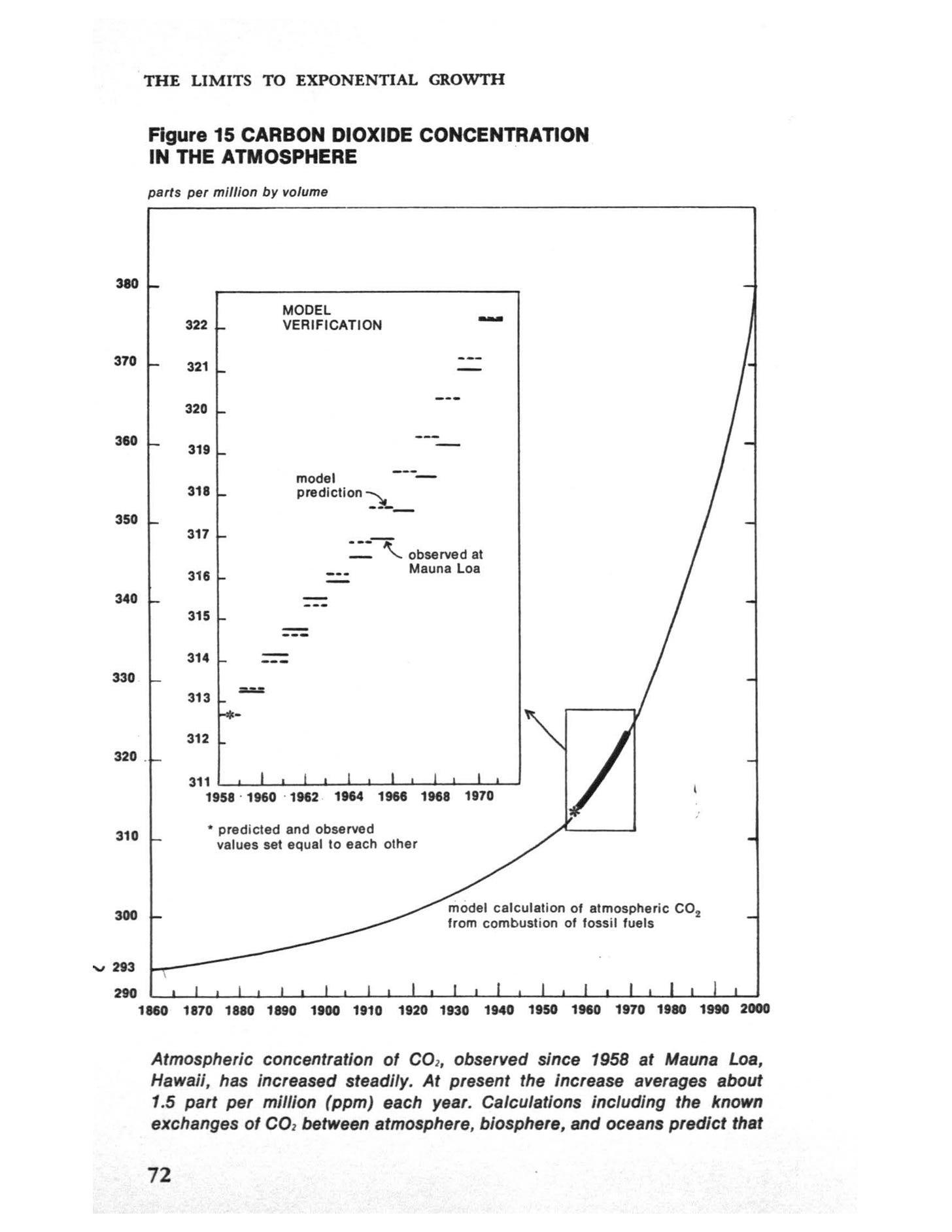

FV: Yes, that's this issue's novelty. Before, you couldn’t only physically feel the environmental problems, but also you could measure and experience them. And suddenly, we were talking about issues that would take decades to document. Only a few years ago, it was repeatedly discussed in the Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change (IPCC) whether the changes were already noticeable and whether the warming caused by CO2 was significant. That put a new quality of environmental policy on the table: We must deal with scenarios and models, which means we still can't determine if these so-called intense weather events are related to atmospheric CO2 levels. In the past 100 years, we’ve seen a decrease in areas affected by forest burning, and there’s also no evidence that heavy rainfall events have increased – none of that data exists, which is why we rely on forecasts and the question ‘What could happen if these atmospheric changes continue? How does that play out 50 to 100 years from now?’ In other words, we've switched from making decisions concluded from empirical observation of nature to future projections based on models. And this raises the big question: ‘How reliably accurate can such models predict the future?’ And there's growing doubt about that...

MB: I’m coming at it from a different corner, namely the history of digitalization I’ve written about, from which you can see bizarre constellations, especially considering this climate issue. An exemplar notes all these model calculations can ultimately be traced back to Jay Forrester’s assistant, Dennis Meadows. And Jay Forrester, who was not only a computer pioneer but also an economist, has always said models are somewhat counterintuitive, a fact that’s often forgotten. But there’s also another fact, which is much more significant: that the solar cell is a by-product of the digitization effort. The transistor was initially a relay and storage device, and the solar cell was a technological byproduct. And while everything revolves around this dimension of abstraction and shrinkage, this whole aspect of digitalization is absent from the conversation. That struck me as absolutely weird. Even remembering - and André Thess was not entirely wrong in pointing this out - that Dennis Meadows' models were not very sophisticated in predicting 100 years of history using only five variables was audacious. And that is how it now reads: Incredibly audacious.

FV: I remember the Club of Rome and Dennis Meadows very well. His models were extremely elementary – and he didn’t even consider Man's rationality and technological development – they merely linearly extrapolated what they saw as the limits. And subsequently, of course, was the forecast in the 70’s of a silver scarcity within eight years. I remember recommending buying silver to my mother because Dennis Meadows said silver was running out – that it would be scarce and expensive – that cost her a lot of money after the price of silver went down from a sudden technological innovation, namely digital photography. After all, silver bromide was no longer needed to make film emulsions. That's the significant shortcoming of these linear developmental extrapolations and why I'm doubtful about any predictions beyond ten to twenty years. I imagine by 2040, we'll have a completely different energy generation technology. For example, fourth-generation nuclear reactors that no longer produce waste are inherently safe and can solve the world's energy hunger. Or think about fusion, which precludes our current policy views.

Policymakers are trying to lock us into today's state-of-the-art by saying, ‘…there won’t be any more new technology in energy production after solar panels and wind energy…that's why we have to use them for 100 percent of today’s CO2-free, renewable energy production.’ They're cutting off all innovative efforts for future generations by burying all the money in these two technologies, which I, too, advocated in the past.

You have to remember that I was a wind power manager and developed solar power at Shell4, which I think are both significant contributions that I’ve made. But now the mistake being made –especially by Germany since we’ve become one of the major forces driving the issue on the wrong side of the road – is believing the world's hunger for energy can only be satisfied using these two technologies. The world map shows that 97 percent of energy comes from other sources. It's fossil sources, it's nuclear energy, it's also hydropower, while solar and wind energy worldwide account for just two to three percent of it. Germany alone believes it will achieve this using just sun and wind energy within the next ten years, while there’s no country in the world – not Sweden, not France, not the USA, not China, not India – going down this path. It's remarkable we Germans think with just these two technologies, we can not only supply Germany’s energy needs, which I doubt, and we can provide it economically – but we also think we can fool the world into believing that they should feel the same. Ultimately, no one will follow our path because it leads to deindustrialization and is too expensive and unreliable - that's why this path will fail in a few years at a significant disadvantage for the German population.

MB: There's something I still don't understand. When I realize that every smartphone has a greater information density than NASA had available when they shot people to the moon – that means each individual essentially has a flight to the moon in their pocket; that’s an unbelievable gain in energy density! If you look at processor development alone, you’d have to say this shrinkage scale is gigantic – meaning that it's incredible that technology advances so quickly. But especially against this background, it is shocking that there's still talk of scarcity.

FV: Yes, undoubtedly, and that’s very important to note as we return to technologies requiring unbelievably large amounts of land for generating energy. The so-called harvest factor illustrates this. Humanity’s development has been struggling for millennia because we’ve never been able to get beyond a factor of three to five. In other words, you had to cut down wood and then use a horse to move it – or harness water or wind power to turn wheels, all having a harvest factor of up to five. Now, we have technologies like nuclear energy with a harvest factor of 100. That means putting one part energy in and getting a hundredfold back, or coal, which is like 60 – but now we're returning to technologies in the range of 5 to 10. Of course, today’s windmill is much better than 200 years ago. Still, its harvest factor isn’t much higher than 10, and solar energy is something like 5 to 10 – meaning we need to consume vast areas of land to produce the same amount of energy. And in the end, that means consuming nature. If you look at...

MB: This Thuringian village in your book...

FV: Yes, yes, to begin with, it is aesthetically terrible. But beyond that, you must consider that its impact on nature is massive. You have to assume that ten bats are killed yearly at every wind turbine and birds of prey in very large numbers. And also insect mortality by wind turbines. Wind energy isn't free to do this. And then on top of that, wind turbines also contribute to local warming because they beat down the air at night, preventing cooling and drying out the soil. So, every energy production has a negative impact somewhere. As I said, I’m a former wind power manager, and that's why there’s an offshore wind power plant bearing my name, Fritz. I'm also proud that I was involved in developing the 5-megawatt plant in Germany, so I accept wind energy; it contributes dramatically in windy areas – just not in Bavaria, where the wind is half as weak as on the North Sea coast. You have to know from the laws of physics that energy yields decrease by a third of its power, which means running the same wind power plant in Bavaria doesn’t cut the output by half, but by an eighth...a half times a half times a half. Trying to make wind energy competitive in places without wind doesn't make sense!

But that German policymakers believe 100 percent of humanity’s growing energy needs can be met with just these two technologies is a grave mistake that will lead to job losses because, in the end, electricity will become more expensive; that's already apparent.

Our current electric prices aren't related to the Russian War; they go back to 2021 when the prices of electricity increased from eliminating nuclear energy and replacing it with more costly renewable energies. Nuclear energy electricity costs 2.5 euro cents, including the final packaging and waste disposal, while today’s wind power costs 8 euro cents, which we see in the electricity prices. Also, with nuclear power, we didn’t need a backup system running in parallel – now we need idle coal-fired and gas-fired power plants for days like today in northern Germany, where we have absolutely no wind and 0 megawatts from the wind. Thankfully, we have a little sun for solar power to offset it, but it slowly goes down, and by 3 o’clock, the coal- and gas-fired power plants have to be started. Running two systems in parallel is expensive, which leads to my concern that we can no longer produce competitively basic materials in Germany because of energy costs. No more steel, or copper, or aluminum, no more of the many chemicals necessary to run our daily lives – or for export; we already see that the energy-intensive industry has declined 25 percent this year, which will cost many valuable jobs.

And there's one more thing our politicians can’t ignore – anyone thinking that the climate will improve if we stop making steel, copper, and aluminum in Germany because it’s made elsewhere must be disabused because it's precisely the opposite.

I've calculated that the same product produced in China has a CO2 footprint three times larger than if it’s made in Germany. In the end, this means we have to fight for every job in Germany because, besides losing jobs and tax revenue, by relocating one of these jobs, we’re also doing something terrible for the climate by emitting three times as much CO2 – climate doesn't care whether the CO2 comes from China, here or anywhere else...

MB: I'm interested in this Don Quixotesque moment where you're fighting windmills with windmills...after all, that's an exquisitely bizarre story! Your harvest factor is critical because asking what has greater efficiency means that pragmatic rationality wins the day. But what concerns me more than anything is precisely this psychological moment, the cognitive dissonance in our politicians. Exemplar is just how planning an energy turnaround is done with no apparent attempts to think through all its consequences completely. This is what Angela Merkel used to call governing by sight, which is nothing more than flying blind. It leads the detached observer, who never wanted to deal with an ideology, let alone become involved in a political party, asking: 'Don't these people actually know what they're doing?' Unlike many politicians, you've taken on responsibility in large companies. You’ve been responsible for building solar panels for Shell, wind farms, and more. And you sat on commissions that advised both the Schröder and Merkel governments, so you know what you’re talking about. Can you shed some light on the world views of those colleagues you came to know when you were an Environmental Senator? How did they come to subscribe to this Don Quixote behavior?

FV: I think that has much to do with the public’s expectations. Politicians have gotten into the habit over the last 15 years of doing what the mainstream expects - what you've called ‘flying blind.' I think Gerhard Schröder was one of the last chancellors to do something necessary for the country's interests– namely, the social reforms of the time, which cost him the election bitterly. These later became known as Hartz IV, transforming Germany from being ‘a sick man into a prosperous society.’ After that, there’s really been only groping about and guessing: ‘What does the majority of the population think?’ Today, we have to consider how the population’s opinions are essentially shaped by media coverage. And if you look at the studies by Kepplinger (97 percent of young journalists vote for either SPD, Green, or the Left), you realize that the media landscape has taken on a Socio-critical left-wing approach, and, in 2011, the first thing they managed to do was slaughter German nuclear power production. Remember the tsunami that year in Japan, which resulted in a terrible nuclear accident that, as we all know, didn’t kill anybody? Instead, any deaths were directly the result of the tsunami itself – but, despite this fact, more Geiger counters and iodine were sold in Germany than elsewhere worldwide...why? Because every evening, the public radio drilled fear into us with its evening program. And that made it possible to talk about phasing out and then closing our nuclear power plants – which didn’t bother us too much at the time because we had cheap Russian gas for generating electricity – and around 70 percent of the population thought we had to stop using nuclear power. Of course, we should have stopped to step closer to look and ask ourselves: ‘Can a case like Fukushima happen here?' If we had, we’d concluded: 'No, it couldn't happen here. It’s just not possible under the laws of nature. We don't have a tsunami area, and waves occur on the Rhine every 100,000 years that are perhaps two or five meters high.' That’s what a reasonable assessment policy would have concluded. But there was another factor at play, which you also have to remember – at the time, Ms. Merkel wanted to build a political bridge to the Greens that nuclear energy was blocking. I think it's always bad when party politics are the priority, not the country's needs, and I’m feeling that again today. You see, amid Germany’s most significant energy crisis, this traffic light coalition is again faced with whether to keep the six nuclear power plants we still have running or shut them down.

It's interesting to see that this time, around 70 percent of the people are saying, 'No, no, no, let's keep nuclear power going; it's crazy to do that and then buy nuclear power from France,’ – which is what we're doing at this very moment. And yet the politicians act contrary to the public’s desire, saying: ‘No, they have to go.' And to me, it’s another illustration of putting party before the country because that would have torn the Greens apart.

So they’ve chosen this path that harms the country and increases the cost of electricity. And it doesn’t help to downplay it by saying only six nuclear power plants supplied only 12 percent of electricity production. People forget that when the cheapest, least expensive power plants are taken off the grid, the merit order of power plant costs to meet the electrical demand shifts to the left, meaning the more expensive gas-fired power plants push electricity’s price to the point of doubling. So yes, to that extent, we have a deeper media landscape problem of putting partisan politics before the country’s interests.

MB: You've given an excellent example with the merit order of cost. Imagine an art auction where they're selling a Picasso painting and a clutter of pretty awful ones, but they’re all priced the same as the Picasso. This has nothing to do with capitalism and the market economy. This moment of merit order cost is when you could say that a kind of ethical opinion...a moral economy, has taken over. And I'm still sitting in before this simple question, puzzling over how you can have a policy where years later you only have to say, 'Yes, I’m sorry…that was a mistake that we got dependent on Russian gas.’ And then I find myself asking: ‘Is the ethics of responsibility over’? What you said about Chancellor Schröder putting the country's interests before his own – I think his shirt was closer to the people. And that's something that needs to be explained. How can a political caste become so deranged and out-of-touch?

FV: Yes, it's a little bit because of how we choose our political elite. It used to be when you had a politician realizing he can’t serve the country with his ideas – or that the majority can't comprehend him doing so, then he leaves politics and pursues a decent profession. When we weren't re-elected in 1997, and the Green Party got into parliament, I said, okay, now I'm going into the market - and became a board member of Deutsche Shell, which I could do because I was good enough to do that. But looking at Politicians today, I think only a fraction of them could get a comparable executive position in the business world – that means now we have a political elite that has to stick to their chair because the privileges are substantial, and the salary is decent. After all, the problem is that the German Bundestag is increasingly gathering parliamentarians who don’t have professional degrees, and a drop-out student is the masterpiece. If I drop out of university at 26, go to the German Bundestag, get 12,000 euros, and have a staff of four, that's sensational. That's a rocket-like rise. And you won't go against the party line because you know you must get on the list again next time. Otherwise, you’ll have a problem with your standard of living. And that's why I think I’m noticing this solidifying, sloping level in politics. It's no accident that, across the country, this administration is considered the worst administration in decades.

MB: I think that a lot of it probably has to do with - and this is a topic we keep coming back to in various discussions - the attention economy, not just what we pay attention to but also saving attention – which means doing things that step into the future and that aren’t necessarily highly valorized. With its governing on sight, Angela Merkel's government team subscribed only to precisely paying attention to demographics and demoscopy in the moment and not the future. But let's get back to the matter at hand. In being attentive to your statistics, it seems clear that an industrialized nation with the highest energy prices in the world is in profound calamity. And if you look at the numbers, you can see how much the explosion in energy prices is due to political factors. The absurd thing is that all the measures having a massive economic impact do very little regarding CO2 reductions. Exemplary is that if we had resorted to lignite, we could have resorted to CO2 ‘capping’ or sequestration. But that technology, although developed at Schwarze Pumpe5 in Germany, is banned in this country. Just like fracking is, while we're happy to buy imported, overpriced liquified natural gas (LNG) imports and, even worse, at the expense of the Third World. This is basically when we talk about issues like social justice and climate refugees, which is complete cognitive dissonance — similar to what happened with bio-ethanol, which then ruined the Indonesian palm forests.

FV: Yes, this isn’t addressed. We actually shut down nuclear power. Then, in 2022, when Russian gas was uncertain – or, rather, blown away – we demanded LNG from the world markets like crazy, which ultimately caused Bangladesh and Pakistan to revert to coal. So that means we destroyed the world markets with our 'whatever it takes' instead of using our lignite reserves. We have enough lignite to last through the next half-century, and could we sequester the CO2 produced from burning it because of this remarkable CO2 capture technology developed in Germany by RWE, Linde, and BASF6 that I worked on and has been adopted worldwide – in fact, RWE is equipping gas-fired power plants in England right now.7 Unfortunately, its use is forbidden here because of the fear factors instrumentalized in Green politics – specifically, the politically created fear that CO2 will eventually bubble out of the ground. This isn’t even scientifically debatable as the CO2 combines with silicates, magnesium, and calcium to form stable dolomites that stay down there safely sequestered; all of that’s been analyzed. Nobody could inject anything at a depth of 1300 meters that could diffuse it, as studies have shown its diffusion rate is something like one meter per million years, which means it's safely sequestered there, and that’s an incredibly invaluable advantage if we used it to off-set burning Lignite here in Germany.

It would also be advantageous to say to the Chinese: ‘Look, we have this technology; we understand that you will want to exploit your coal resources to generate prosperity and economic growth – but then please capture the CO2 so the levels don’t continue to rise.'

As you’ve rightly pointed out, the second thing to note is that natural gas extraction by fracking is banned in Germany8. Instead, we get it from the U.S., where it’s much more environmentally damaging because, after the extraction process, they leave their drilling sites open, resulting in methane release and groundwater contamination from leakage through the borehole itself – rather than doing it here, using our safer German/EU extraction methods. Again, the key driver here is fear factors. The first is that the shocks caused by the underground high-pressure hydraulic injections at a depth of 1,000 meters could reach the surface and lead to faults – and this is coming from a country that’s dealt with mining damage in the Ruhr region for 100 years that says: ‘if we can control anything, it's something like that.’ The second fear factor was saying, 'Well, then the groundwater will be polluted.' That's stupid, too, because the groundwater is at a depth of 200 meters, and fracking the shale gas is at about 1,000 meters, where you can safely extract it to the surface without contacting the water using double-walled pipes. So we also have enough gas for the next 20 to 30 years, which we could independently produce safely and cheaply within a year while saving our industry – and it's not being done – why isn't it being done? It's because although the Chancellor knows this, he's deliberately decided against using it because he's afraid as soon as the first drilling rig goes down in Lower Saxony, there will be a massive demonstration by Fridays for Future or Last Generation – in the end, the media will ensure that the solution can’t be carried out. It’s no longer possible to take controlled risks in Germany – and if you don't take risks, you don't get opportunities – and you can't make any progress either, which is the dilemma of having an energy policy driven by a fear of the world coming to an end. I can reassure them that the world will not end in the next 100 years. It’ll get a little warmer, and we’ll have temperatures in Hamburg or Frankfurt that are 0.3 degrees warmer, which we can easily cope with. But we need to discuss why German Politicians, the German public, and the German media are so eager to paint this picture of Armageddon to push through a particular policy. This heat pump discussion with its encroachment into household basements is entirely insane – our government is telling us, the public they serve, what we must do without looking at the specific needs of our different houses and different financial situations – then mandating we all must install heat pumps by such a date. And it’ll only decrease our CO2 emissions by 1.4 percent...that’s absurd! And they're not even listening to us! We're blowing 130 billion euros on an ideological bill that could be better spent on education, infrastructure, and railway...

MB: Now we're getting into a problem where you see a dysfunctional political staff that can no longer effectively manage. But this goes back much further: If you see that the magnetic train was developed in Germany and then used in China; if you see that the safest nuclear power plants in the world were developed in Germany by Siemens; if you see that CO2 sequestration was successfully developed in Germany with the Black Pump – then you can see this leitmotif emerging over the last 30 or 40 years isn’t entirely new. If I were to analyze it ideologically, I would say that this has something to do with the failure of the Left-Wing’s utopian prospectus, when they said to the workers, 'We want to liberate you’ – but the workers defiantly responded, 'No, we don’t want to be liberated by you. You better go over into the GDR, where the air is even worse than in the West.' Nature doesn't contradict. You can commandeer nature to empower yourself politically, making it a perfect intellectual and spiritual tool. You can see this in brilliant people like Bruno Latour, a sociologist who was very involved with this climate issue. Amazingly and profoundly shockingly, he took on Carl Schmitt’s thinking as self-empowerment at the end of his life by proclaiming a State of Emergency. He said we have to do political theology and do it in the direction of climate. When suddenly the abettor of National Socialism becomes the promoter of the climate movement, then something goes wrong. And this is Politics becomes Aesthetics. FV: Yes, I believe the climate debate is being used to achieve socio-political goals that couldn't otherwise be pushed through. If we’d been discussing 20 years ago whether we should cut back on automobility in Germany, doing away with gas and diesel cars, you and I would have said, ‘Forget it, that's never going to happen.’ Everyone was far too aware that one in five jobs depends on automobiles, on the indispensability of people's needing to decide when and where they want to go freely – yet today, because of the climate debate, we’re faced with the situation that not only the gasoline engine is being eliminated, but the diesel ban is set for 2035. But what’s more, electromobility can't satisfy our mobility needs since you won't be able to drive daily on electricity when you want to – forget about that because the grid isn’t capable of providing electricity whenever we need it. In other words, we will end up with rationing and quotas where you're allowed to drive 50 kilometers a day, and if you want more, you’ll have to apply for permission or pay significantly more – how did this come about? Driving has been identified as harmful to society because of its CO2 emissions. 'It's people like you who drive a car' – or if you're a school child, then you are taught 'It’s your father who drives a big diesel car that’s polluting the climate – and do you want people elsewhere to suffer from your activities?' That’s a successful game strategy as you've just managed to limit people’s mobility with climate fear – and we can continue doing this in so many directions in a society that’s been renouncing its religious orientation over the last 50 years because, with the climate debate, we have all the ingredients of a new religion – and because it’s about faith, you can't tell the climate alarmists anything. If I tell them, ‘Guys, what you're doing here is entirely nonsensical because even if you could bring the gasoline and diesel-driven passenger cars in Germany down to zero – it still wouldn’t have an effect worldwide because, according to Professor Sinn9, the oil will be burned somewhere else – it depends on how much oil is demanded worldwide.’

MB: The Green Paradox ...

FV: Our sacrifice means that others will get it cheaper. But they won't grasp that. They’ll say, ‘No, no, I believe in it!’ You have all the ingredients here; you have purgatory, the sinner and the repentant sinner too – and the indulgence trade in CO2 certificates. Who knew today’s electricity situation, which is so dramatic for every individual and industry, would be so politicized? In its background, European CO2 certificates have unbelievably quadrupled in cost – and who is affected by this? It’s not France or Sweden that have nuclear energy and water; it’s Poland and primarily Germany because we have coal instead – that’s why our electricity prices are going through the roof, which is politically intended to make the indulgences of CO2 expensive. I make something expensive if I want to penalize you for using it and vice versa...the state takes the money, around 15 billion euros, from emissions trading – redistributing it into the technologies it wants you to use, such as wind and solar energy, which hardly anyone notices. But nobody knows about that – there are so many reasonable arguments that favor introducing a correction in Germany – but they keep hitting the wall of people having a firm conviction ‘that Germany is finally on the side of the good guys now, and we're saving the world by going under – and we have to do this for the sake of others, even if it means suffering the penalty of our own demise.’ If you’re against this belief, things can go very badly because it’s only when people finally are in such a terrible predicament that they send their representatives and spokespersons to the devil, as we’ve seen in church history.

MB: The sale of indulgences is such an excellent exemplar because the indulgences treasury was born in the very moment when capitalism was born, in the moment when the first Florin, the first Genovino...the first gold coins in the Middle Ages began circulating. And then the church comes along, which is already on a sinking continent, trying to gain unquestionable supremacy by saying, ‘Well, we also have a treasure’ – you could call it a public-private partnership, and that's a very bizarre constellation because all of a sudden, the laws of capitalism start to migrate into the psyche.

One of the strangest stories is that indulgences had a serial number on them to control counterfeiting – meaning they are the original form of the dollar. The ‘in God we trust’ is actually the indulgence letter in which we see, all too briefly, this cognitive dissonance asserting itself subliminally.

This touches on a point I don't understand…like when we saw the sudden air traffic paralysis during the Corona Crisis; we thought, ‘That’s okay because we’ve got Zoom, so we can communicate even though we can’t fly.’ But without digital media, that wouldn't have been possible, and nobody even considers that this may be our new operating system’s architecture – that's something I never understood about this whole energy thing. You could have said, ‘Okay, we're entering a new world. The old top-down technologies, the old monopolies – all of which used to be state-owned enterprises before they were neoliberally transferred to the market – we now want to make a market-based,’ where everyone can become a producer in this world where, like the Internet, it comes down to paying attention to the information. And then the most critical point in this whole story would have been about having the smart grid, precisely what you're writing about: ‘What do you do when there's too much electricity? What do you do when this miracle of a 50-Hertz secure energy supply no longer works?’ You have to shut down the wind turbines because you don’t have any saved information about the system to regulate its excesses and deficits.

FV: Yes, there’s one thing we shouldn’t forget, which is that even though people often say, ‘Yes, we can all supply ourselves, we have solar energy on the roof, and we still have a battery in the basement, and that’ll power my car too,’ we keep forgetting that only 25 percent of electricity consumption comes from homes – the rest of the 75 percent comes from industry and transportation like railroads. I don't have the fantasy of harnessing solar energy from our homes and then using it to power steel mills – that's very quixotic – that's why I think this is where decentralization will reach its limits. There's nothing wrong with a house being self-sufficient; that’s great. Even though batteries are a little too expensive, I'm sure that’ll eventually be worked out; nevertheless, it doesn't solve our problem.

China has built 130 gigawatts worth of coal-fired power plants, all within the first half of this year, which is about four times what we still have here – are they doing this because they're so stupid and somehow so reckless? No, because as Xi Jinping said, it's a question of economic efficiency for them to start building right now as the climate is a distant second priority, which is regrettable. And it’s not right that China is still considered a developing country by the UN and therefore doesn't have to do anything10. We have to take this into account in our political actions.

After all, what use is it to me if I’m now importing copper from China made with coal because I’ve destroyed my own copper production here in Germany? Perhaps instead of following the strict faith of climate change and jumping off the cliff, we should first stop and say, 'Is that really what everyone wants?’ I don't think so, and that's why we're seeing a lot of resentment among the population from noticing increasingly restricted personal freedoms...that they're being robbed by increasing burdens imposed on them which they can't see as making any contribution to solving the crisis...I don’t ever remember seeing such a loss of party loyalty in the last 40 years.

MB: Complete d'accord. You could almost say it's practically a neo-Malthusian policy – but this begs the question: ‘Where did this come from?’ No conservative government could have come up with that. You’re a man of numbers as befits a natural scientist. And here we come to the borderline, which I find so puzzling, where the logical inconsistencies of the energy transition are blatantly outrageous. In your book, The Great Energy Crisis, you always find the phrase: ‘How to do this remains the German government’s secret’…that ‘the bill can be sent to sun and wind’ may be Mr. Alternative Energy’s11 nice campaign slogan, but if you calculate the total price, you’ll have to concede if the whole world uses wind power technology, it would use up all of the planet’s rare earth resources in nothing flat. Where does this ataraxia of insensitivity come from? FV: You’re absolutely right, as wind turbines are becoming more expensive because the raw materials are becoming more expensive, which contradicts the mantra of politics – and there's not much discussion about that either. I don't know if your audience knows that last December, the German Federal Network Agency secretly raised the electricity feed-in tariff for wind turbines from 5.8 to 7.3 euro cents – that’s 25 percent! And that’s not the end. If you continue doing the math, you’ll see that we’ll need around 200 billion euros to transform the grids into a decentralized system. Additionally, it’ll require more investment systems that can store months’ worth of fluctuating wind energy for long periods of wind lull – I've done the math, and it’ll be 14 to 15 euro cents, which would mean the end of German industrial activity.

But we don't discuss the reality of infrastructure needs and cost; instead, we’re told: ‘Yes, yes, but we have a problem now, and it's become more expensive because of Putin.’ Maybe that’s true for gas, but not electricity, which is the huge debate about subsidizing industrial electricity. To make it more palatable, the government is saying, ‘We'll only do it for five years because then the prices will go down,’ – but that's not true because solar and wind energy economics essentially consist of two factors, namely material and capital with capital becoming more expensive and material becoming scarcer.

Copper prices have doubled in the last three years, steel has become more expensive, as have the rare earths you’ve mentioned, and even plastics are becoming more expensive. All materials will naturally become more expensive. Then there's the question: ‘How do I get reliable electricity from a volatile source?’ It doesn't help just estimating kilowatt hours usage per year; you must know the exact kilowatt hours needed at any particular second. For instance, when an ICE train leaves the station, the extra electricity it draws from the grid must be available at that very second. At the same time, wind energy isn’t reliable as the wind could be increasing or decreasing at that moment, necessitating the expense of storage and backup needs. So, like you, I keep returning to the question: ‘Why can't we discuss such obvious things in Germany?’ We need a German Bundestag Enquete Commission debate on what’ll happen if energy prices go up in 2030, not down. Squeezing increasing amounts of industry subsidies from the taxpayer can't be the goal of a society, not even of a market economy; it's a straight path to, shall we say, socialism light – we've been down that road before where, in the end, no matter how profitable and efficient the production is, the state-subsidized it. This was then called VEB12 ...

MB (laughing): ...Animal production...

FV: Whatever...VEB Energie or just VEB – that's what we're running into while this debate isn’t being held. I can only wish people would wake up to what’s happening because this road only leads to more state empowerment that’s trying to control everything right down to your basement. It’ll soon manage your mobility because the networks won’t be able to satisfy those needs at all times – not to mention that electric mobility charging in a major city is already a technical problem – in the end, this will all lead to losses of freedom currently unimaginable. And then there’s the food debate of ‘How much meat should people be allowed to eat per week?’ – all supposedly because it helps the climate. And that's why the real mother of all battles to be fought is the question: ‘Just how dangerous really is the alleged climate crisis? Does it really justify the massive interventions we’re facing?’ If you look at the figures from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), you'll see that by a longshot because it's manageable and controllable. Yes, we will have 40-45 cm of sea level rise; we’ve already dealt with that in Hamburg13. Even in my time, we have raised the dikes by one meter, which can be done again, but it also means we have to decrease the CO2 emissions – only we have to do it with the proper means, which, in my book, I propose as nuclear energy combined with renewables. Renewables are most definitely part of it, but not 100 percent. We must also produce our own natural gas using our CO2 sequestration technology. I’m really optimistic about this because it’s under our feet in northern Germany and will still be recoverable in five years. The crucial question is: ‘What state will our economy and industry be in by then? Will we be able to get back up and running again?’ MB: When I think about what has happened with the energy transition, I’d compare it to someone jumping out of an airplane and saying to himself, ‘I’ll be able to sew myself a parachute on the way down to earth. So I want to get out of a system; I'll do it.’ That's complete cognitive dissonance. I sit in front of it, thinking this isn’t how capitalism has evolved. Good systems have adopted even better systems – but not by being taken over by wishful systems. Joseph de Maistre wonderfully said: ‘The road to hell is paved with good intentions.’ There’s no need to argue about climate; all you have to say is that certain things should have been addressed if you had wanted to go down this political road, which hasn't been addressed. The smart grid is simply not there. That is…

FV: They should have built the grid first, then wind power, not vice versa. Because then you have to shut down the wind power while paying for it – without that, the windmiller wouldn't invest in wind power. In other words, we first should have said, ‘We're going to build a grid, and then we can afford it.’ It’s the same thing with the heat pump...I have nothing against implementing its use, but it should be rolled out in new buildings rather than mandated for all, which requires a certain amount of political patience. That’s saying, ‘Yes, we can't radically turn a society upside down in five years that’s developed over 150 years. We mustn’t forget one thing because we are always talking about our parents and grandparents and great-grandparents' generations as if they had only one thing in mind the whole time, namely destroying the planet.’ Over the past 150 years, we’ve developed an incredible civilization. This is illustrated wonderfully in Hans Rosling's book Factfulness, where you see life expectancy has been doubled and birth mortality reduced by 40% of its initial value, which we have to acknowledge has been a success story for humankind primarily because of the expansion of fossil energy sources – imagine what would have happened if we couldn’t send airplanes when there was a food crisis. Granted, we’re seeing that CO2 has risen with adverse effects. However, this needs to be carefully examined as climate scientists like to paint everything in the worst colors so they can be heard and influence politics. Let's look at the core of the IPCC's most probable path. We aren’t facing a catastrophe but a manageable path of controllable development – even though temperatures may rise by another 0.3 to 0.5 degrees by 2051, that's not the end of the world – and we have to do it in a very generational way, not in the next five years.

Other nations seem to see this more realistically – the Chinese say 2060, the Indians say 2070 – so I think it’s a profound misunderstanding of the German Federal Constitutional Court’s belief that CO2 remains eternally in the air. On the contrary, the Earth is becoming greener because about half of the CO2 is absorbed by plants and the oceans.

Even if we only had half of the projected emissions levels, a new equilibrium would emerge as a temporizing solution, meaning it's less dramatic than believed. But we have to notice the propensity for dramatic presentation to generate fear, always asking what’s the real driver behind this. Is it maybe in realizing social utopias that otherwise wouldn’t have been realized without this driver? That was the Left's dream of a society controlled by the state, down to the last detail, down to every utterance and every activity. This conflict must be solved so we can escape this fear and see an open future to develop practical solutions rather than the past mistake of generating solutions based on fear of social change.

MB: We had a conversation with Dickson Despommier a few days ago. I don't know if you know him? He and his students were the first to promote the idea of vertical farming, which realizes something quite simple – that arable farming accounts for 80 percent of the world's land mass. In contrast, vertical farming is easily eight times more productive. And if you consider this increase in productivity also makes fertilizers largely superfluous, and that it's also water and environmentally-friendly, then the answer is a no-brainer. Not to mention how absurd it is having blueberries flown in from Peru when I can produce them locally. We’ve now come to a curious question: vertical farming requires energy for the LED lights that come from semiconductor technology and use much less energy than the old metal halide bulbs. But now farms in Holland are complaining about the massive increase in energy prices – so, it's safe to say vertical farming is developing less dynamically than it could because of this connection: energy on the one hand and environmental protection on the other, which gives back to nature something that has been taken from nature. Absurdly, Dickson Despommier developed the whole thing in New York and thought, okay, if we just used the empty high-rise buildings, green them, we could supply 20 percent of New Yorkers from the city. That makes this cognitive dissonance perfectly clear, right? You'd have to produce more energy to be able to go greener.

FV: Yes, you point out the significant fact that we need inexpensive, competitive, and environmentally friendly energy as a solution to humanity’s problems – that's about food and also about producing clean water, especially looking at the increasing water scarcity in populous regions needing water desalination which isn’t getting used. Why? Because it costs energy, which is expensive and implies whoever fulfills humanity's energy dreams with fusion or new inherently safe nuclear fission technologies will not only produce cheap energy but will be able to solve every problem. This is humanity's most significant task because food, clothing, mobility, and water all depend on the central energy factor. And we're now on the path of making the harvest factor of energy smaller and more inefficient – and that worries me. For example, you need to go where the wind energy is, like in Patagonia, where you can do it for two euro cents – but it seems no one is thinking about using Nature’s Treasures of wind or solar radiation where it’s practical. Using solar energy in Schleswig-Holstein, where there are 800 hours of sunshine, is stupid when we have 2,400 in Morocco - anyone can do the math and calculate that's a factor of 3, which means it's three times cheaper in Morocco – so let's do it in Morocco and not in Schleswig-Holstein. I’m not advocating renewables should be thrown in the garbage can, but that they should be used where they’re inexpensive, meaning effectively beneficial for contributing to the other issues you mentioned, such as food.

MB: I think one of the most important triggers for the current calamities is paying homage to the hopelessly romanticized concept of nature without realizing that the solution doesn’t lie in the logic of Degrowth – but in more intelligence. As Robert Zubrin said, ‘To save the natural, we must embrace the artificial.’ If you do that, as vertical farming wonderfully shows, you can give back to nature what you have taken from it. I assume that would have been precisely your impulse as an Environmental Senator to argue for fracking, for CO2 capping, for nuclear power, for any intelligent solution that leads to environmentally friendly policies...

FV: You end up questioning whether it's an extensive or intensive solution. As Senator for the Environment, I fought very hard to maintain the nature reserves in Hamburg, which was at the forefront of Germany with, I think, eight percent of its area. But I also saw we needed space for industrial concentration in certain areas – that’s what you’re bringing up in the question of energy politics: Do we want to extensively supply our energy production needs using 100 to 200 square kilometers of land or intensively using maybe two square kilometers of land for a fusion power plant? And naturally, that applies to food. As much as I support organic farming, it takes three times as much land, so it is wiser and more efficient to intensively produce the same amount of food using only one-third of the land, giving the other two-thirds back to nature. But that’s not possible today because everything has to be extensively organically farmed, no matter what else the productive soil is needed for, which is a significant mistake. Of course, we have to worry about groundwater pollution contaminating agricultural production and the like, but to believe we can satisfy ourselves 100 percent through organically-farmed agriculture is a misconception because, in the end, we will have to import food from countries that need it for their self-sufficiency.

MB: Talleyrand, in a beautiful remark to Napoleon, said, 'Monsieur, what you have just done was worse than a crime; it was stupidity!' And it’s in this dilemma that I get into a certain doubt, asking myself, when and how did these stupidities begin? That is also, strictly speaking, the question of deindustrialization. Doesn't this have a long history? Let's look at the education system’s decay. The dysfunctional infrastructure and the lack of digitization, which would be seen as a form of postmodern illiteracy, go back a long way. And so far, small and medium-sized enterprises, Germany's hidden champions, have been able to stand up to this decline. But the current energy policy is the real nail in the coffin. And as you mentioned earlier, we’re dealing with a classe politique that, let's say, has a particular problem with deciphering realities and is professionally rather precarious. I would say that the issue of the dark period also has an intellectual side. Or is that too harsh a judgment? FV: Yes, maybe it started when we thought we were doing very well... beginning in the 80s and 90s, when all our needs were more or less satiated. Some people are starting to talk about our wealth neglect, meaning we’ve only taken care of issues that made our lives nicer. And that gives me hope because, as this feeling of prosperity dissolves, Germany will again refer to its secondary virtues as Helmut Schmidt's critics did: diligence and integrity, civic-mindedness, and social justice and invention. The question is: How fast is the beat of destruction versus the beat of knowledge?

MB: I like to make a little joke about an old Victor Hugo saying: ‘That nothing is greater than an idea whose time has come,' – where I say: 'Nothing is greater than an idea whose time has passed.' Because you can suddenly get them below the cost of actually doing the work of saving attention, and you can use them, like Don Quixote, to run against windmills because he knew the heroic stories of the Middle Ages. What we have today...

FV: Yes, I like that, that saying. The idea that’s gone out of its time. Nothing is worse than an idea that has gone out of time.

MB: This is precisely the very moment when this intellectual home museum becomes our political situation. It’s when people settle in a moral economy that's only about the stories of the past but not the future. I used to ask my colleagues: ‘What is your idea of the future in ten years?’ That was a saying that still worked quite well in the 1990s, but in the 2000s, it became strange when people began saying, ‘I'll be happy if next year goes well.’ That's what the yellow vest movement has mercilessly brought to the fore: ‘You think about the end of the world, we think about the end of the month.’ That’s the conflict – and this lack of a future has something to do with the fact that society is taking refuge in the past and losing its rationality. And I believe the price we have to pay for this kind of flight from the present is the hysteresis of coming too late – and that’s a price akin to buying non-Picassos for what a Picasso costs. I fear that the German self-image, the country of tinkerers and engineers, is quickly becoming a thing of the past if this de-industrialization continues.

FV: Yes, I think that's a very remarkable thought. We talk about the future almost every day, but always in gloomy colors about the world coming to an end. The discussion has turned 180 degrees from when I was a student in the 70s and the world before me, so to speak, a world of opportunity, advancement, prosperity, and justice. I’m a Social Democrat, as you know, and the secret of Social Democracy is this promise of advancement, where you can work your way up. I also come from a poor background, and it’s vital to have an open society with open education systems that allow you to work your way up into a better life – and I want my sons to have a better life! That is the impetus for many who are now having their homes taken away from them. It’s the impetus for a whole generation: ‘I save so that my children will have a better life one day, and that's why I work overtime and am willing to do more than others.’ And this idea of performance is being trampled underfoot at the moment – no, it’s even worse than that because it’s being turned into the opposite where the future promises only destruction, floods, Armageddon, and the migration of people. Young people draw their conclusion from this, which I can understand as: ‘I have no future anymore.’ Because that's what they're told every day, and, as a rule, they start out doing quite well having a lovely nursery, and their parents probably take them on flying vacations – and then they superglue themselves ...

MB (laughs)

FV: Something has undoubtedly changed, and of course, that makes me think that this defeatist, pessimistic image of the future is shaping an entire generation of youth. And what kind of people are emerging from this? What kind of lives are they leading? I always like to bring up the example that there’s hardly any greater satisfaction for a high school student than solving a complex mathematical equation. But now, this experience of accomplishing something, creating and understanding something, always has a lower value.

Now it’s ‘No, we don't need to learn anything, we know it all already! We already know that CO2 destroys everything.’ And when I ask young people how much CO2 is in the air, they say: ‘20 percent.’ And I say: ‘Really, that much? Could it also be 0.04 percent?’ And the reply is, ‘Nah, Nah, that's a lie...that's a conspiracy theory!’ So I ask: ‘Do you actually know because of the increase in CO2, that crop yields are going up...that the yield of wheat and rice and from our fruits has gone up 15 percent? Just imagine 15 percent less worldwide famine catastrophes...did you know that already?’ To which I hear: ‘Nah, that's not true; that's conspiracy theory.’ So I ask: ‘Didn't you learn about photosynthesis in biology class?’ And then I hear: ‘Nah, so what is that? We don't know photosynthesis. That's some conspiracy theory.’

So there it is – returning to your question – the future is distorted; it’s even being programmed as a negative expectation in our youth. And that's quite dangerous...

– Translation by Hopkins Stanley and Martin Burckhardt

Related Topics

Talking to ... Dickson Despommier

Talking to ... Roger Pielke jr.

Talking to ... Robert Zubrin

The saying goes back to the Girondist Jan-Pierre Vergniaud, who remarked in 1793 when the Jacobins were getting rid of their bourgeois rivals: The Revolution is like Saturn; it eats its own children. That was his last sentence before the guillotine came down on him.

Seveso is a town in Italy that in 1976 experienced a dioxin disaster, which resulted in both initial and long-term adverse health sequela for the local population, and that Fritz Vahernholt wrote a book about titled Seveso ist überall: D. tödl. Risiken d. Chemie [Seveso is Everywhere: The Deadly Risks of Chemistry]. [Translator’s note]

He worked at the Federal Environmental Agency’s [Umweltbundesamt] Department of Chemical Industry from 1971 through 1981 in Berlin; was Senior Ministerial Council in the Hessian Environmental Agency from 1981 until 1984; when he became Hamburg’s Environmental State Councilor from 1984 until 1990, then led the Hamburg Senate Chancellery from 1990 through 1991 before becoming the Hamburg Senator of Environmental Authority [Umweltbehörde] and Chairman of the HEW [Hamburgische Electricitäts-Werke AG] Supervisory Board from 1991 until 1997. [Translator’s note]

In the late 1990s-early 2000s, Shell plc began investing in renewable energy sources, including solar, wind, hydrogen, and bio-fuels, which they sold off while continuing to invest in new oil and gas reserves. Curiously, they’ve restarted making investiture in carbon sequestration, supplying household energy and broadband, home solar-battery storage, sustainable aviation fuel, electric vehicle charging stations; most recently, renewable electrical generation and storage networks (albeit too late), and renewable natural gas in Europe where subsidies guarantee their financial solvency. [Translator’s note]

The Schwarze Pumpe power station was built in 2006 at Brandenburg’s Black Pump industrial area as a pilot project providing steam for nearby factories using an oxy-fuel combustion process to make capturing the CO2 from burning lignite more efficient. The pilot project was designed to capture, compress, and liquefy the resultant CO2 stored underground, where it becomes naturally geologically stable as a prototype for larger power plants. Although the design was sound, climate activists began criticizing the project in 2005 because they believed it diverted funding from developing renewable energy; research was stopped in 2014 because it was found to be economically unviable. [Translator’s note]

RWE, BASF, and Linde partnered in 2007 to develop a carbon scrubbing process for flu gases. In 2009, the three announced a breakthrough recovery rate of 90%. [Translator’s note]

In 2023, RWE announced feasibility testing of the retrofitting of three gas power plants with their de-carbonizing technology. [Translator’s note]

Historically, hydraulic fracking of Germany’s sandstone gas reserves started in 1975, with more wells receiving fracks than any other European country between 1978 and 1985. The country lacked specific regulations, and in 2013, Angela Merkel’s government announced new draft fracking regulations in line with U.S. techniques that were retracted within a month because of the German public’s response – essentially banning German fracking from that point on, and, in 2016, Der Bundestag officially passed the law prohibiting the practice. [Translator’s note]

Hans-Werner Sinn is a German Economist known for his early work on theories of economic risk, economic cycles, environmental economics, and other economic areas. In 2012, he began studying the problem of global warming, publishing an article titled Public Policies against Global Warming, followed by the publication of Das grüne Paradoxon [The Green Paradox], which describes how environmental policies that become greener over time essentially lower the cost of fossil fuels in the long-term – thus inducing their suppliers to accelerate resource extraction which contributes to global warming.

The UN considers China a developing country, which exempts it from various climate change responsibilities. It is also currently the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases and the second-largest economy. [Translator’s note]

VEB is an acronym for Volkseigener Betrieb [Publicly Owned Enterprise], which was the East German form of industrial enterprise. [Translator’s note]

Hamburg is situated on Germany’s coast, between the North and Baltic seas on the Jutland Peninsula, which has been slowly eroding with an estimated rise of 15-25cm/100 years. Hamburg had elevated its surrounding dikes and seawalls twice, first in 1962 when the North Sea flooded 1/6th of its area and again in 2017 when the storm Sabine resulted in the Elbe River rising by 2.76 meters. [Translator’s note]