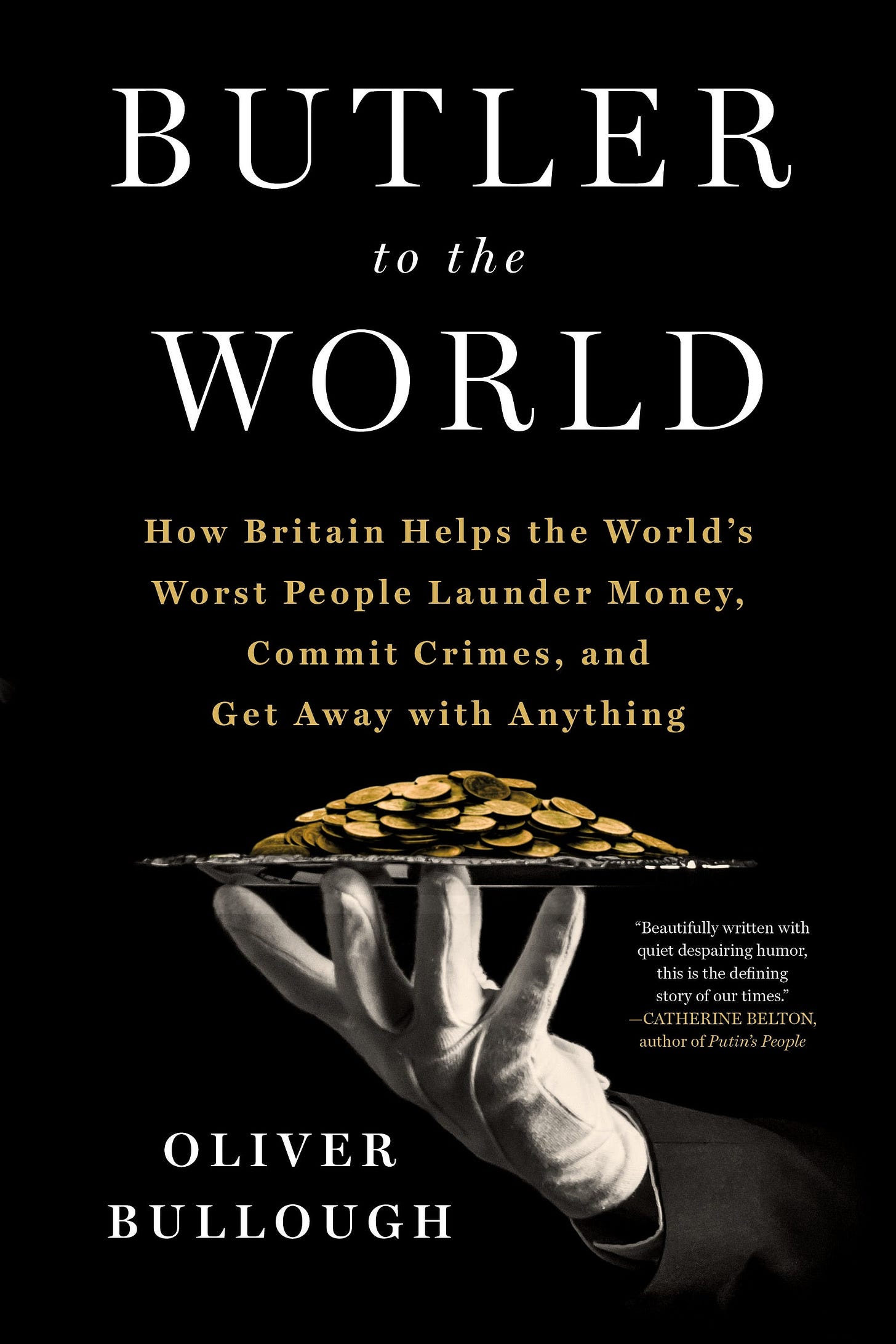

Some books tell of a deep, abysmal story in a somnambulistic way – and Oliver Bullough's Serving the World belongs in precisely that register. You could call Bullough an anthropologist of money. In any case, he lends a psychological meaningfulness to a story, which has been rather sheepishly circumnavigated with the weasel word of neoliberalism, that's completely lacking when we're only looking for a scapegoat. At the same time, he succeeds (much better than many political scientists) in focusing on the symbolic civil war that’s subtly destabilized societies of the West. But what is his story about? It's necessary to say a few words about the history that has sensitized the author. As a young man who had grown up on a sheep farm in Wales and studied history at Oxford. Later he ended up in Russia where, as a journalist, he was able to observe at close quarters how the hopes of Russian society for prosperity and democratization were becoming increasingly dashed – and how an oligarchy, indeed a kleptocracy, was spreading, which to achieve its goals, wasn't afraid of using the Russian mafia, which enjoys the resounding name: Thieves in Law. As a Reuters correspondent, Bullough covered the Chechen war and, after returning to England, delivered a psychogram of its demise, The Last Man in Russia. The Struggle to Save a Dying Nation. What struck him as bitter during his years in Russia was observing how the plundering of Russian national wealth was often accomplished with the help of Western, not least British, advisors. This set the stage, so to speak, for Bullough's focus on money laundering – and the criminal practices that increasingly dominate financial transactions. Against this backdrop, Butler to the World can be understood as an attempt at fathoming why an extremely cultured, indeed snobbish, class – the English posh milieu – could deign to assist mobsters in laundering money. Or, as the book's subtitle puts it with beautiful clarity: How Britain helps the World’s Worst People Launder Money, Commit Crimes, and Get Away with Anything.

Its story is about nothing other than a form of British Breaking Bad – only the protagonists, as in the comedic series of the same name, don't appear as arch-villains but as thoroughly pleasant, cultivated contemporaries. Bullough locates the story’s beginning in the British Empire's decline, which becomes apparent in its final days with the Suez Canal crisis. General Nasser's nationalization of previously privately owned oil companies was the trigger – something the old colonial powers weren't prepared to accept. However, their attempt to overthrow the general, whom they denounced as Egypt's Hitler, failed – this, in turn, brought the British Empire's weakness into sharp relief ( which the local colonizers had long since been aware of). If the fall of the Empire (which at its height had ruled a quarter of the globe's land mass) was a socio-psychological humiliation of the first order, it certainly had practical implications. Suddenly, an entire generation of administrators, who'd made themselves comfortable in a faraway land, looked after by butlers and servants, were deprived of their status and privileges. This functional aristocracy's loss of importance weighed all the more heavily because it wasn't certain that an even remotely attractive position was waiting for the colonizers back home – quite the opposite. Because despite having won the war, England in the 1950s was sliding into a deep economic crisis. What was the answer to this aristocracy that had become superfluous? Here, Oliver Bullough's book unfolds the journalistic craft of an intelligence entirely his own. Instead of getting lost in post-colonial theory, he follows these characters' lives – and, in this way, makes clear the strange metamorphosis his protagonists are undergoing. There’s the story of a lawyer with an Oxford law degree who would have had the whole world open to him – but suffers from a kind of postcolonial shock. Born in Tanzania and educated in Kenya, he'd just spent two years in England – and had nothing drawing him to return there. On the other hand, the situation in his African homeland wasn't very enticing – so when he received an invitation to become a partner in a British Virgin Islands law firm, he accepted it with glee. The business opportunity could be curiously understood as an administration of insolvency. You see, the functional aristocracy of the British Empire had become accustomed to a somewhat lax tax morality overseas, where the controls were not so severe – consequently, those enjoying the exception, as a rule, were by no means inclined to submit to the strict tax legislation of the mother country. This led to a phenomenon that would go down in history as Funk Money – capital withdrawn from the colonies in search of a safe haven that could save it from the grasp of the British tax. This was precisely the law firm's mission that’d set up shop in the British Virgin Islands. Even though there wasn't a more backward place in the entire colonial empire, the mother country's partial autonomy to the colonies offered a certain freedom of movement – making it ideal for money laundering. And, since the business was booming, these resourceful lawyers came up with all kinds of new business ideas. Since it was equipped with a fax machine, it was also possible to contact the American continent, making it easy to offer even the unwilling American taxpayer a safe haven because, at this address, money could be deposited in the account of a Caribbean mailbox. In some ways, the moral problem didn't weigh too heavily as people overseas were accustomed to laxer customs. Thus, the Empire’s privileges could be continued – while, on the other hand, they were assured that if they didn’t provide this service, someone else would.

This is precisely the story that Oliver Bullough tells in various twists and turns, using various exemplars of different protagonists: for instance, how Gibraltar, a rock in the Mediterranean, was able to transform itself from a military post that'd become superfluous into an online gambler's paradise – an Eldorado modeled on the Caribbean tax havens. Here, it wasn't the funk money that was at stake, but the question of whether the high tax burden of British betting offices could be alleviated – and in this way, the entire British betting business could be transferred to a spot with a population of just 20,000. Because this bargain coincided with the possibility of online gambling, Gibraltar soon found itself fortunate to have almost all British betting shops in the country. Conversely, the expansion of gambling services resulted in a further spread of betting addiction in Great Britain – and subsequently, every British person (including infants, the elderly, and the demented) spent a good 2,000 pounds of their income on bets annually. Following this logic, you can understand why in 2008, when the financial crisis broke out, a good 35% of England's gross national product was generated by financial services – and why, even in the Motherland itself, highly questionable practices were spreading – and all this actively supported by well-educated, soigné gentlemen who pursued their day's work with unshakable pragmatism in the firm knowledge that if you didn't do it yourself, someone else would do it for you. This short book review doesn't presume to retell Oliver Bullough's financial thriller in an abbreviated form. This is something the author can do so much better – and in doing so, he tells a story that goes completely unmentioned in the discourse on the excesses of neoliberalism, a story in which kleptocrats, economic advisors, and tax lawyers shake hands.

The only criticism that could be levied against this superbly researched and excitingly narrated work of journalism is on a theoretical level – which may well be the subject of another conversation we'll have with Oliver Bulloughs (after the last one, regrettably, fell victim to a technical error). Here, it's about a missing link; more precisely: it's about the technology that both explains and controls the seemingly erratic behavior of its protagonists. It's no coincidence the creation of the first tax havens coincides with the end of Bretton Woods, or more precisely, the foundation of a world financial system. The fact that the decoupling from the gold standard took place in the shadow of the Arpanet, the integrated circuit, and the Unix era (1.1.1970) is a circumstance that's been unceremoniously overlooked even by the economic profession's greats. The consequences, however, are well known to us; indeed, they're familiar in an almost everyday way. From then on, capital was no longer at home in the capitals but was evaluated by the faceless world financial markets, and these actors, in turn, required a technical network to do so. This parallel narrative made the book even more exciting to read. We understood that going into the limbo economy doesn't merely owe itself to the moral flexibility or the postcolonial shock experience but is accompanied by a technical seduction. Starting with the fax machine, via the Internet of the early 1990s to real-time communication and the emergence of avatars and phishing practices, we can trace how classical institutions are increasingly undermined – and the pragmatism of the helpers slips into the semi-silent if not into criminality. Following this trail, you can resolve the psychological paradox that Oliver Bullough describes with great empathy in his portraits and stories. This makes it clear that his protagonists, who’ve slid down a slippery slope, aren't arch-villains – but people like you and me, realists who adapt to circumstances, knowing that the opportunity you fail to seize for yourself will be someone else's profit. It's here, in the human-all-too-human, that the scandalous becomes palpable, which Bulloughs seeks to address with his metaphor of the butler who reads his lord and master's every wish from their lips. This role may perhaps apply to the aging administrators of the British Empire, but it fails to recognize that we're dealing with a historically effective force: Opportunity makes thieves, as the saying goes. In this sense, what we call 'neoliberalism' may be a ruthless opportunism in which the digital revolution is pitted against the old institutions.